|

December 2001, Volume 23, No. 12

|

Original Article

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Effectiveness of a community continence promotion programM M L Hsia 夏鎂玲,Q W W Mok 莫慧華 HK Pract 2001;23:532-539 Summary Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of a community continence promotion program conducted by physiotherapists in the female elderly population. Design: Prospective data collection by questionnaire. Subjects: Female elderly from 6 local elderly centres were invited to participate the program in June 2000. Main outcome measures: Knowledge on incontinence and continent status of the subjects were evaluated before, after and one-month after a continence promotion program. Results: 363 elderly women attended the program. There was a general misconception about incontinence and bladder habits amongst elderly women. The prevalence of urinary incontinence was 40.8% but only 11.7% of them sought help for their problem. More than 80% of the participants complied with the pelvic floor exercises and bladder training advice taught during the program. After the program, their knowledge was significantly improved, t=10.54(140) (95% CI 1.25-1.82), p=0.000. There was a significant association in the continent status and lower urinary tract symptoms between pre-program and one month after the program (x2 test p=0.000).

Conclusion: A community continence promotion program

that includes lower urinary tract anatomy and physiology, good bladder habit and

pelvic floor exercises is an effective tool for primary care of incontinence. Keywords:Incontinence, primary health care, elderly, female, pelvic floor exercises 摘要 目的: 評估由物理治療師在社區年長女性開展的一項改善排尿控制活動的成效。 設計: 使用問卷前瞻性地收集數據。 對象:來自6個本地老人中心的女性,於2000年6月開始。 測量內容: 分別在提升排尿控制能力活動前、活動結束時及活動後1個月,評估參加者對排尿失禁的了解 及其排尿控制的能力。 結果: 共有363位年長女性參加本活動。她們對老年 女性尿失禁及排尿習慣一直都存有誤解。老年女性尿失禁的流行率為 40.8%,但僅有11.7%的人因此而求助。80%以上的參加者能持續地進行在活動期間所學 習的骨盆底肌肉運動和遵照排尿訓練指示。在活動結束後,他們的相關知識大大增加( t=10.54(140) (95% CI 1.25-1.82), p=0.000)。在活動前和1個月後,排尿控制能力和下泌尿道症狀的發生有明顯相關性( x2 test p=0.000)。 結果: 共有363位年長女性參加本活動。她們對老年 女性尿失禁及排尿習慣一直都存有誤解。老年女性尿失禁的流行率為 40.8%,但僅有11.7%的人因此而求助。80%以上的參加者能持續地進行在活動期間所學 習的骨盆底肌肉運動和遵照排尿訓練指示。在活動結束後,他們的相關知識大大增加( t=10.54(140) (95% CI 1.25-1.82), p=0.000)。在活動前和1個月後,排尿控制能力和下泌尿道症狀的發生有明顯相關性( x2 test p=0.000)。 結論: 在社區,一項包括介紹下泌尿道結構和生理、 訓練排尿習慣和骨盆底肌肉運動的促進排尿控制活動是改善尿失禁問題的有效方法。 主要詞彙: 尿失禁,基層醫療,老年,女性,骨盆底肌肉練習 Introduction Urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine.1 Common types of incontinence include stress, urge, overflow and functional incontinence. People who are incontinent may have concomitant lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as urinary frequency, urgency and nocturia. The prevalence of urinary incontinence is between 13 and 50 percent in both Eastern and Western societies.2-6 The occurrence of urge incontinence and urgency tends to increase with age.4 Despite the high prevalence, both public and health care providers seldom talk about urinary incontinence due to its sensitive nature. There are misconceptions and lack of knowledge on urinary incontinence in women aged 23 to 38 years.7 Less than half of the women who are incontinent seek help for the problem.3,8,9 Previous study showed that community dwellers who were silent about their incontinent problem in fact wanted to know more about the management of incontience.6 In Hong Kong, public health education programs are conducted on a variety of topics, for example, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and smoking. It is therefore thought that a continence education program may be culturally appropriate in providing information on urinary incontinence to community dwelling population. Since elderly women are at a greater risk of developing urinary incontinence, this health promotion program was run in local elderly community centres as a starting-point of community continence care. There is a paucity of literature on the outcome of a public health education program. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a community continence promotion program conducted by physiotherapists in the female elderly population. Materials and methods Subjects Women from 6 elderly centres were invited to the continence promotion program. Participation in the study was voluntary. Tools Each questionnaire survey was divided into two parts.* The first part was a list of ten questions on general knowledge of incontinence and bladder habit (Q-K). The second part questioned the continent status, treatment seeking behaviour and the disease-related quality of life (Q-C). The latter was modified from the questionnaire written by the first author (MH) with reference from the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire.6,10 In this study, urinary incontinence referred to the leakage of urine associated with coughing, sneezing (stress incontinence), or with a feeling of urgency (urge incontinence). The continence promotion program included the following topics: definition and prevalence of urinary incontinence, lower urinary tract and pelvic floor anatomy, factors associated with weakening of the pelvic floor, common types of urinary incontinence and management methods including bladder training and pelvic floor exercises (PFX). At the end of the program, the participants were taught how to perform a pelvic floor contraction and were advised to practise it several times a day. The program was conducted by a physiotherapist (MH). Each continence promotion program lasted one hour. Procedures The questionnaire Q-K was conducted prior to the program (thereafter called 'pre-program test on Q-K'). Verbal consent was obtained from the participants and they were then asked to answer ten questions. The survey Q-C (thereafter called 'pre Q-C') was conducted by the other investigator within one week after the program. The pre Q-C survey was presumed not being affected by the program as it reflected the continent status of the participant in the month prior to the time of survey. The investigator conducted the follow-up phone survey on Q-K (thereafter called 'post-program test on Q-K') and Q-C (thereafter called 'post Q-C') again one month after the program. The study had obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals. Statistical analysis Data was entered into the Statistical Package of Social Science on an IBM computer. Descriptive analysis was performed and the results were reported descriptively. Test for association between variables was performed using Chi-square test. The change in knowledge acquisition prior to and after the program was compared using paired t-test. Results

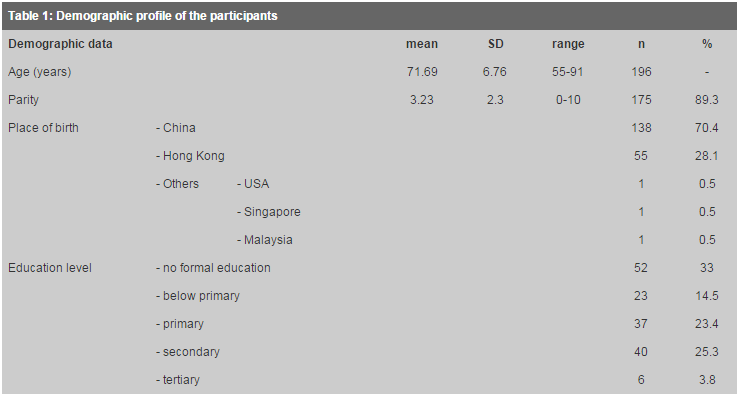

A total of 316 women volunteered to do the pre-program test on Q-K (Figure 1).

Three hundred and one pre-program test on Q-K were valid and gave a mean score of

6.06

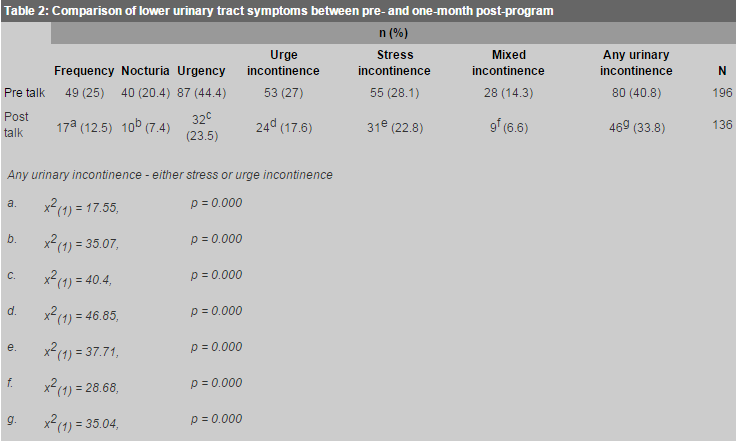

One month later, 141 women were successfully contacted and completed the post-program test on Q-K with a mean score of 7.66?1.45 (range 3-10). This time 14 women got the maximum score. A significant improvement in knowledge was obtained in women who completed both pre- and post-program tests, paired t-test, t=10.54(140) (95% CI 1.25-1.82), p=0.000. Prior to the program, nearly all subjects thought that in general, people should void immediately once they got an urge, and most thought that it was normal for elderly people to be incontinent. On the other hand, most of them knew that they should drink six to eight glasses of water everyday. After the program, there were significant positive changes in the responses in most of the questions. However, one-third of the subjects still thought that generally people should void immediately once they got the urge. The prevalence of urinary incontinence was 40.8% (n=80). These women either had stress incontinence (28.1%), urge incontinence (27%), or mixed incontinence (14.3%). The prevalence of urinary incontinence one month after the program was 33.8% (n=46), with 22.8% stress incontinence, 17.6% urge incontinence, and 6.6% mixed incontinence. There was a significant association in the continent status and LUTS between pre-program and one month after the program (x2 test p=0.000; Table 2). The occurrence of urinary incontinence was not associated with age, place of birth and number of vaginal deliveries.

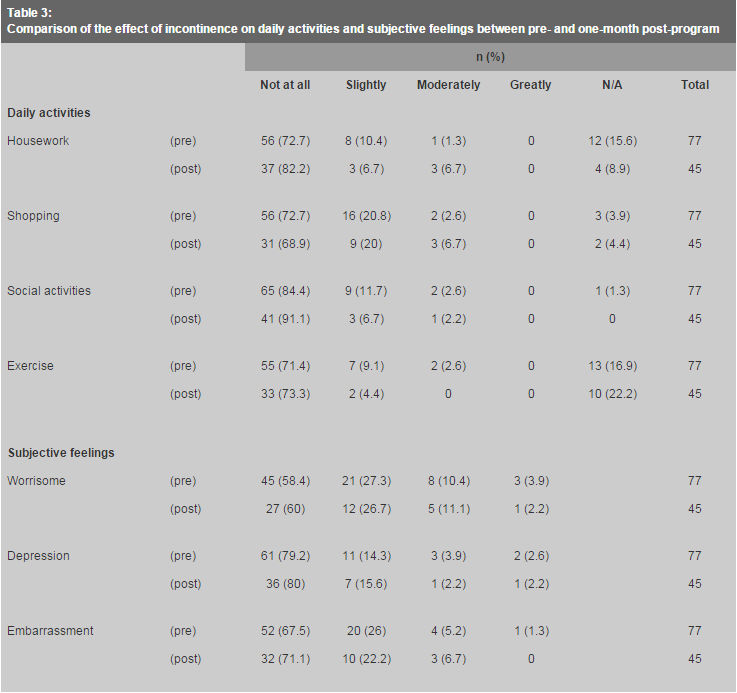

For those with urinary incontinence, only 11.7% (n=9) women sought help for their problem within the month prior to the program. Of these, half of them asked a friend (44.4%), and the others consulted general practitioners (22.2%), specialists (22.2%) or nurses (11.1%). None talked to their family about their incontinence. Those who did not seek help either considered urinary incontinence a normal ageing process (25%), not severe (20.6%), or did not know where to get help (20.6%). In the pre Q-C, despite leaking moderate to large amount (n=44, 57.1%) and frequently (from weekly to twice daily; n=39, 51.4%), most participants considered their condition was not or only slightly affecting their daily activities and feelings (Table 3).

More than 80% of the subjects reported compliance to PFX and bladder training advice taught during the program. Fifteen out of 46 women who reported incontinence in the one-month post-program follow-up survey requested medical consultation. They were referred to the Continence Clinic. Sixty-seven percent of them required urodynamic investigation for confirming the diagnosis. Eighty-three percent improved both clinically and subjectively in one-year follow up. Of those who did not request for medical intervention, some reported improvement in their problems in the one-month follow up phone survey, while others claimed that they would seek medical advice if the condition persisted. Those who withdrew from the post-program test Q-K were half continent and half incontinent, while all women who withdrew from the post Q-C were continent. Otherwise, there was no difference between the demographic data of the two groups of women. There is, however, incomplete data for analysing attrition. Discussion There is a paucity of literature on the effect of a public health education program. The present study has shown that a one-off educational talk on incontinence is associated with an improvement in knowledge and continent status in community dwelling elderly women. There is strong evidence to show that behavioural treatment, which includes bladder training and PFX, can reduce symptoms of urinary incontinence, and are hence recommended as the first line of management for individuals having the problem.11,12 Based on this, Sampselle et al13,14 and McFall et al15 evaluated the efficacy of a public health intervention model on women with urinary incontinence. They demonstrated that the delivery of behavioural treatment could reduce urinary symptoms up to one year post-intervention. The authors recommended this educational model as a management option for self-reliant women with moderate levels of urinary incontinence. The present study further supports that behavioral technique is beneficial for women as a self-managing tool for LUTS. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in the community dwelling elderly women in this study is 41%. It is higher than studies done on a general female population in Hong Kong (13-22%),4,5 and is much higher than an elderly population in Singapore (4.8%).16 The discrepancy can partly be due to sampling differences. For example, the subjects in this study have other comorbidities which may play a role in urinary incontinence. But it is worth noting that the most common medical illness among the participants is hypertension (36%) which is also common among the elderly in Hong Kong. Furthermore, in the present study, women attending the elderly centres were invited to attend the continence promotion program. Therefore, women with LUTS might be more motivated than continent women to attend the program. The former might also have more incentive to leave their names and phone numbers as they might consider it a good chance to talk to a health care professional about their condition. However, there might still be an under-estimation of the condition, as this study only reported the occurrence of urinary incontinence in the past month, and those with occasional leakage would have likely been missed. While literature shows that compliance to PFX is generally low, the reported compliance in the present study is encouraging. In a structured interview with 28 women regarded as non-compliant to PFX, Ashworth and Hagan17 concluded that the lack of feedback and a sound rationale behind the importance of PFX deterred women from doing the exercise regularly. The high compliance in the present study can partly be attributed to the detailed explanation of the anatomy and function of the pelvic floor, and the importance of the preventive and curative role of PFX in urinary incontinence during the program. In addition, the reinforcement provided during the phone interview might have served as a motivator and follow-up action. Voluntary participation in the program may also suggest that these women may be more motivated in pursuing exercises taught in the program. The findings3,6,8,9 that few women seek help for their incontinent problems are further supported by this study. The low help-seeking tendency may be partly explained by the small impact of incontinence on their quality of life. This study also demonstrates that women have a general misconception about bladder habit. Health care providers should be proactive in providing knowledge on LUTS and bladder habit to the general public. Clinical implication There is a steady increase in the life expectancy of females over the past decade.18 The escalating elderly population anticipates a corresponding increase in health care demand. Therefore there exists a definite need to shift the health care paradigm from curative to preventive medicine. Public health education has been utilised in providing information on self-care in various health conditions like heart diseases and diabetes mellitus. The extension of this model into urological care in the elderly population in this study has proven to be an effective tool to improve public knowledge and pre-existing symptoms. The screening effect of this program allows the specialised clinic to be more effectively and efficiently utilised, and target the services to those who reported clinically significant symptoms. As urinary incontinence is considered a social taboo, women may be loath to discuss it even when being asked individually. The high turn-up rate and active participation have reflected that health education programs may be a culturally appropriate method to provide information on sensitive topics. Women who had never been taught PFX before were motivated to do the exercise after thorough explanation and follow up action, resulting in the high exercise compliance rate. This model of primary health care may be particularly important to women who are self-reliant in managing LUTS like urge incontinence. Ability and confidence to defer urination may reduce the risk of fall and fractures in elderly, especially those having some limitation in mobility.19 Limitation The effect of the behavioral techniques on the subjects' symptoms may be limited due to concomitant underlying problems such as prolapse, fibroid and use of certain medication. For example, the use of diuretics in people with hypertension may be associated with an increase in urinary frequency and urgency. Furthermore, some of the subjects may not be able to perform PFX correctly just by verbal instruction. Conclusions This study has shown that a community continence promotion program is effective in improving the respective knowledge, symptoms of incontinence and LUTS in community dwelling elderly women. As urinary incontinence is considered a social taboo in many cultures, health care providers should be more proactive in bringing up this topic in a culturally appropriate manner, and dispelling the stigma of incontinence. It is thus recommended that public health education on incontinence and bladder habits be broadly introduced to the community, especially in areas with a high geriatric population. Acknowledgements We thank Dr Gabriel Ng of Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, for his statistical advice, Dr Teresa K K Yu, Mrs Joanne Tsang and Mr Michael Chung of Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals, Ms Annie Au of Southorn Centre for their full support in this study. We also thank the volunteers and the elderly centres for their enthusiastic participation.

M M L Hsia ,PDPT, PgDPT(Women's Health), MPT(Women's Health) Q W W Mok, PDPT, MSc in Health Care (Physiotherapy)Physiotherapy Department, Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospital. Correspondence to: Miss Q W W Mok, Physiotherapy Department, G/F, Ruttonjee Hospital, Wan Chai, Hong Kong. References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||