December 2001, Volume 23, No. 12 |

Update Article

|

|

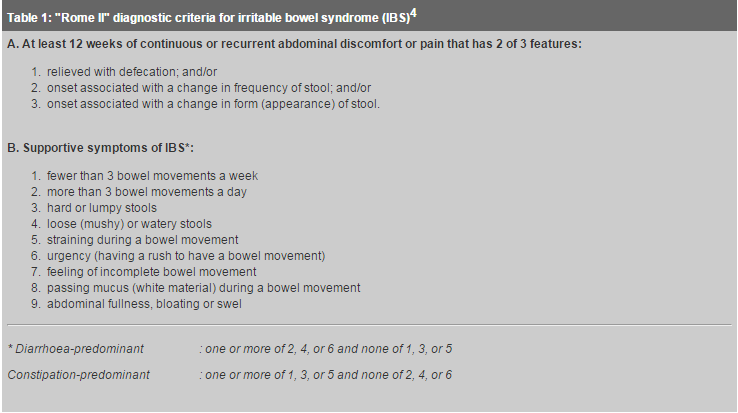

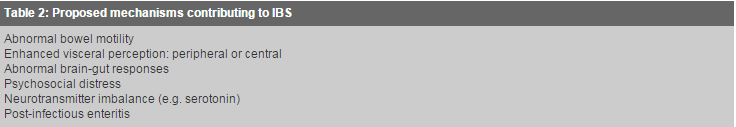

Pharmacotherapy of irritable bowel syndromeV K S Leung 梁景燊 HK Pract 2001;23:554-559 Summary Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common disorder diagnosed by gastroenterologists and one of the more common ones encountered in general practice. Management of patients with IBS is based on positive diagnosis of the symptom complex, limited exclusion of organic diseases, reassurance, and institution of a therapeutic drug trial. IBS continues to be a therapeutic challenge because of its diverse symptomatology and lack of a single pathophysiological target. Pharmacological agents currently used for IBS are targeted at a predominant symptom such as pain, diarrhoea, or constipation. Ongoing research studies using a novel group of pharmacological agents that bind to serotonin receptors are proving promising in the treatment of IBS, particularly those that bind to 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) and type 4 (5-HT4) receptor sites. 摘要 腸激道綜合症是腸胃病學家最常診斷的病症,它 也是在門診較常遇到的病症。治療是根據臨床表現做出診斷、排除有關的器質性疾病、消除病人疑慮和藥 物治療。由於此病徵狀多樣化及缺少單一病理生理學的指標,所以治療此病仍然是一個挑戰。目前用於治 療的藥物針對主要病徵,如腹痛、肚瀉或便秘。研究中的新藥,5 -羥色膠受體競爭性抑制劑(尤其是5-HT3及5-H T4)為治療帶來新希望。 Introduction Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is among the most common of gastrointestinal disorders, affecting up to 20% of the population in western countries and accounting for 12% of primary care and 28% of gastroenterology practice.1 There is a clear female predominance with a female to male ratio of about 2:1.2 IBS comprises a group of functional bowel disorder in which abdominal discomfort or pain is associated with alterations in bowel habit. Diagnosis is based on identifying positive symptoms known as Rome criteria3 (Table 1) and excluding organic diseases in a cost-effective manner using minimal diagnostic studies. The exact pathophysiology of IBS is not known and numerous mechanisms have been proposed to elucidate the cause of the disease. Table 2 summarises the pathophysiological mechanisms that appear to contribute to the development of IBS. Interaction between different mechanisms may occur in individual patients.

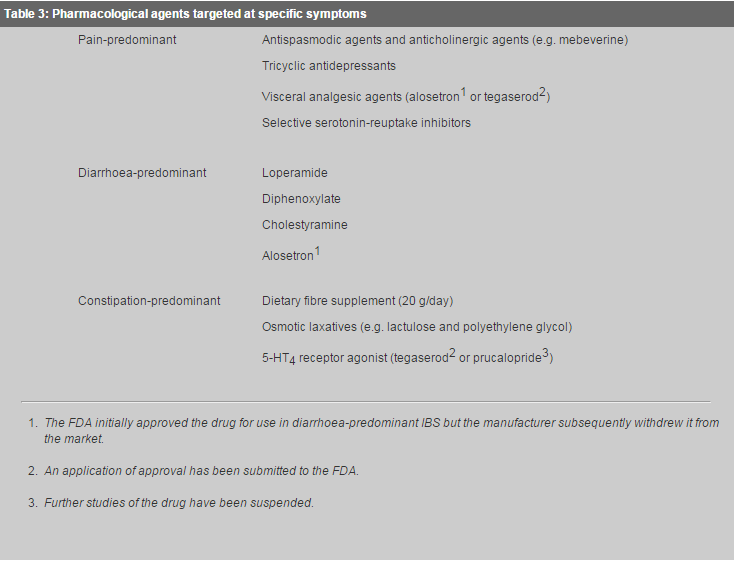

Effective treatment of IBS remains a challenge to primary care physicians and gastroenterologists. The cornerstone of treatment for patients with IBS is a successful patient-physician relationship, reassurance, education, and lifestyle and dietary modification. Patients with mild symptoms commonly require no other therapies. Pharmacological treatments are generally recommended for patients with moderate to severe symptoms, and psychological interventions may be indicated for those with debilitating symptoms and/or associated psychosocial difficulties, such as depression and anxiety.1 Pharmacological agents currently used for IBS are aimed at a predominant symptom (Table 3), although success is variable.

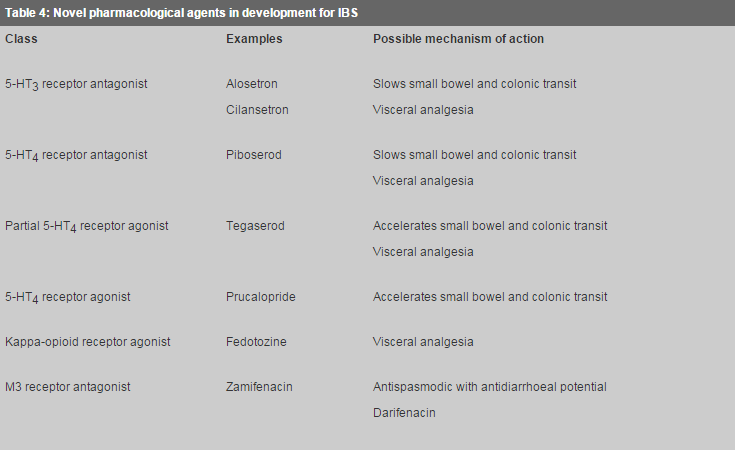

Role of fibre in treatment of IBS High-fibre diets are widely accepted in treating IBS, especially for patients with constipation. Constipation may improve if sufficient quantities of fibre (20-30g/day) are consumed, whereas its value in relief of abdominal pain and diarrhoea associated with IBS is controversial. In fact, some patients may even experience worsening of symptoms, especially abdominal distension, bloating, and flatulence, with higher doses of fibre. The uncertain benefits of fibre are the basis for common practice of starting with a low dose, increasing gradually, and abandoning high levels of supplement (e.g. >30g/day) if patients experience worsening of symptoms. Antidiarrhoeal agents Loperamide, a synthetic peripheral mu-opioid receptor agonist, is preferred over diphenoxylate for treating patients with IBS who have predominant diarrhoea because it is poorly absorbed and does not traverse the blood brain barrier. Moreover, diphenoxylate is available only in combination with atropine (Lomotil) and may induce adverse effects that may be worrisome in the elderly, e.g. urinary retention, glaucoma, and tachycardia. In patients with IBS, loperamide (2-4mg, up to 4 times daily) decreases intestinal transit, enhances intestinal water and ion absorption, and increases resting anal sphincter tone, thereby improving diarrhoea, urgency, and faecal soiling.4Cholestyramine is considered a third-line treatment in patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS because of poor palatability and low patient compliance. This drug may be considered in a subgroup of patients with cholecystectomy or who may have idiopathic bile salt malabsorption.5 Smooth muscle relaxants Antispasmodic agents have been the cornerstone of therapy for many patients with IBS. Data from clinical trials, however, are difficult to assess and compare because of research design, significant dropout rates, high placebo response rates, and dissimilar measured outcomes. Nonetheless, cumulative evidence of available studies supports the efficacy of smooth muscle relaxants in patients whose predominant symptom is abdominal pain.6-8 In their first meta-analysis of smooth muscle relaxants in IBS, Poynard etal showed that five drugs were efficacious over placebo: cimetropium bromide (a quaternary ammonium antimuscarinic compound), pinaverium bromide and otilonium bromide (quaternary ammonium derivatives with calcium-antagonist properties), trimebutine (a peripheral mu, kappa, and delta opioid agonist), and mebeverine (a derivative of b-phenyl-ethylamine that has antimuscarinic activity).6 The commonly prescribed antimuscarinics, dicyclomine and hyoscine, were not effective in the meta-analysis.6 An updated meta-analysis by Poynard etal7 and another systemic review8 confirmed the efficacy of the above five antispasmodics in the treatment of IBS. At this time, only trimebutine, mebeverine, and otilonium bromide are being marketed in Hong Kong. In clinical practice, antispasmodics are best used on an as-needed basis up to 3 times per day for acute attacks of pain, distension, or bloating. Antispasmodics with no anticholinergic activity or antimuscarinics which possess fewer systemic anticholinergic effects (including urinary retention, tachycardia, blurred vision, and xerostomia) are clearly more desirable. Newer antimuscarinics, including zamifenacin, with muscarinic type 3 receptor (M3) selectivity, are undergoing study for efficacy and safety. These muscarinic M3 receptor antagonists have reduced affinity for M1 (gastric acid secretion) and M2 (heart rate control) receptors and hence fewer anticholinergic side effects. Antidepressants Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g. amitriptyline) are used increasingly for treatment of IBS, particularly in patients with more severe or refractory symptoms, and those with associated depression or anxiety. In addition to their psychotropic effects, TCAs have neuromodulatory and analgesic properties which may benefit patients independently.9 TCAs tend to cause constipation and thus are probably best reserved for those patients with diarrhoea and pain-predominant IBS. Doses much lower than those prescribed for treating depression are frequently effective in IBS patients (e.g. 10-50mg amitriptyline). Furthermore, the onset of action of antimuscarinic and analgesic effects of TCAs occurs much sooner than the antidepressant effect (24-48 hours). Nevertheless, a 2-3 month trial is usually needed before a therapeutic benefit can be excluded. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g. fluoxetine) are increasingly preferred over TCAs because of their lower adverse effect profile, they have not been evaluated for use in patients with IBS. SSRIs tend not to cause constipation and may even induce diarrhoea in some patients, and thus may have a role in patients with constipation-predominant IBS. Anxiolytics are sometimes prescribed for patients with IBS because these patients frequently report symptoms of anxiety. However, these agents are generally not recommended because of weak treatment effects and a potential for physical dependence.1 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) antagonism in IBS In recent years, the availability of agents with visceral analgesic and sensorimotor-modulatory properties has stimulated much interest in the field of IBS therapy (Table 4). Identification and characterisation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), or serotonin, receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors which are involved in sensory and motor functions of the gut, has led to a number of therapeutic trials of IBS targeting these receptors.

5-HT is released from enterochromaffin cells of the mucosal epithelium in response to chemical or mechanical stimuli. The mucosal action of 5-HT is to stimulate intrinsic and/or extrinsic sensory neurones.10 Intrinsic sensory neurones, which are activated by 5-HT1P and 5-HT4 receptors, initiate peristalsis and secretory reflexes. Extrinsic sensory neurones activated through 5-HT3 receptors initiate noxious sensations from the bowel, which may include nausea, bloating, and pain. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists appear to reduce visceral sensitivity to colonic distension and have inhibitory effects on motor activity in the distal intestine. Alosetron, a selective 5-HT3 antagonist, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in relieving pain, improving bowel frequency and stool consistency, and reducing urgency in female patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS.11 The most common adverse event with alosetron treatment is constipation, occurring in up to 30% of patients.11 A significant adverse event with an unclear relationship to alosetron is ischaemic colitis, estimated to occur in 0.1% to 1% of patients. There had been 49 cases of ischaemic colitis and 21 cases of severe constipation, including instances of obstructed and ruptured bowel. This eventually led the manufacturer to withdraw alosetron from the market in the USA in November 2000. The mechanism for colonic ischaemia is unknown and it remains to be determined whether this is an adverse effect confined to alosetron or represents a class effect common to all 5-HT3 antagonists. If it is the later, then this could present problems for all of the other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (e.g. cilansetron) in development. 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 (5-HT4) agonism in IBS New partial or full 5-HT4 receptor agonists appear promising in the treatment of constipation or constipation-predominant IBS. Tegaserod is a selective 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist which has been shown to accelerate small bowel transit and tended to hasten colonic transit in patients with constipation-predominant IBS.12 Phase III randomised, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled trials have been performed demonstrating the efficacy of tegaserod in the treatment of abdominal pain, bloating and constipation in female patients with IBS.13,14 Thus far, it has been demonstrated to be safe and well-tolerated except for the adverse effect of transient diarrhoea in about 10% of recipients. In vitro studies suggest that tegaserod, in a range of concentrations likely to occur during clinical use, does not delay cardiac depolarisation or prolong QT interval of the electrocardiogram as does the benzamide 5-HT4 agonist/5-HT3 antagonist cisapride.15 More than 10,000 electrocardiograms from participants receiving tegaserod have been analysed to date, with no increased frequency of QTc interval prolongations or dysrrhythmias recorded.16 Based on the results from these phase III trials, an application for approval of tegaserod in the treatment of IBS has been submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Prucalopride, a full 5-HT4 receptor agonist, has shown promise in treating patients with functional constipation. However, phase III clinical trials are currently on hold because of concern of potential intestinal carcinogenicity in animal species. Conclusion IBS is a common disorder that has a pronounced effect on the quality of life. Management of patients with IBS requires an integrated and individualised approach to treatment, with a foundation based on a successful patient-physician relationship. In addition to effective pharmacological agents, the emotional and psychological aspects of the patients need to be considered in a successful management plan. With greater insights into enteric neuroscience, novel therapies are being developed that make a more comprehensive approach possible.

V K S Leung, MBBS(Syd), MRCP(UK), FHKCP, FHKAM(Med)

Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to: Dr V K S Leung, Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics,United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, , Kowloon, Hong Kong. References

|

||