January 2001, Volume 23, No. 1 |

Original Article

|

|

Clinical depression and severe marital maladjustment in an unemployed sampleS T C Jang HK Pract 2001;23:4-9 Summary Objective:To discover the percentage and severity of clinical depression and marital maladjustment in an unemployed sample. It was hypothesised that a significant percentage of the unemployed subjects would suffer from clinical depression, and also a significant percentage would suffer from severe marital maladjustment Design:Each subject completed the Beck Depression Inventory, the Brief Screen for Depression, the Dyadic Adjustment Scale, and demographic information. Subjects:Two hundred and twenty-one unemployed male and female subjects, aged 18 and above, who came to a Hong Kong non-governmental social service agency to receive services for the unemployed. Main outcome measures: Cut off scores for clinical depression and severe marital maladjustment based on the above three scales. Results:Around 30 percent of the subjects scored within various levels of clinical depression, and almost 25 percent of those previously or currently married suffered from broken marriages or from severe marital maladjustment Conclusion: The two major hypotheses were supported. A high percentage of our sample suffered from clinical depression (30%) and severe marital maladjustment (25%). These alarmingly high figures called for proper diagnosis and timely intervention by professionals. Keywords:Major depression, marital problem, unemployment, Hong Kong Introduction Hong Kong economic recession and unemployment rate Economic recession and unemployment have been the focus of attention in Hong Kong since 1997, following the Asian financial crisis. The media reported major department stores closing, workers laid off and salaries reduced. The government sectors initiated major systemic changes within the civil service and also promoted the Enhanced Productivity Program. The Hong Kong unemployment rate increased from 2.2% in 1997 to a record high of 6.3% in April 30, 1999. (Table 1) In the first quarter of 1999, compared to a year earlier, the teenage unemployment rate soared by more than 70 percent to 18,000.1 As a result, there was an increase of requests to welfare agencies relating to unemployment and financial difficulties in Hong Kong.2 Economic recession and mental health in Hong Kong A 1998 study named “A Survey of Hong Kong People’s Psychological Health”, conducted jointly by the University of Hong Kong Psychology Department and Radio Television Hong Kong, revealed a 27% decrease in the 1998 score (26 points) compared to 1995 (36 points), indicating decreased psychological health among Hong Kong people within a three-year period.5

Furthermore, after the financial crisis, between its onset in 1997 and the third quarter of 1998, the average number of new patients on the waiting list of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority’s Psychiatric Unit increased six-fold. Suicides resulting from unemployment also saw a big leap; it was reported that in 1997, unemployment accounted for 48% of the suicide cases.6 Objectives and hypotheses Studies in foreign countries provided ample evidence that unemployment was detrimental to both physical and mental health.7 Studies from a few Hong Kong agencies found that unemployment was not only a financial problem; its aftermath included both emotional and family problems.8-10 However, these studies used only a few items to assess the subjects’ emotional and family conditions. The present study attempted to use reliable and valid psychological scales to measure depression and marital adjustment. It was hypothesised that a significant percentage of the unemployed sample would suffer from clinical depression, and also a significant percentage would suffer from marital maladjustment. Method Subjects The sample consisted of 221 male and female unemployed people, aged 18 and above, who came to Christian Family Service Centre, a Hong Kong nongovernmental organization, for services for the unemployed from June 1, 1998, to April 26, 1999. The services they received included the following:

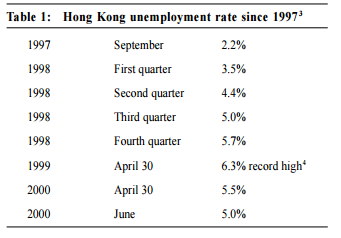

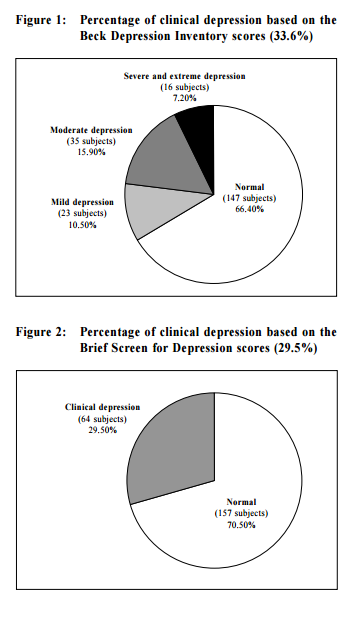

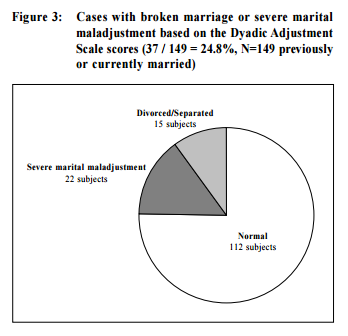

Out of 257 distributed questionnaires, 221 completed questionnaires were returned, giving a total return rate of 86%. Survey questionnaire and instruments Each subject completed a self-report questionnaire booklet which included two depression inventories, a marital adjustment scale, and demographic information. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): The BDI is a 21-item scale, developed by psychiatrist Aaron T Beck. It is the most commonly used instrument for depression. Each item is scored 0, 1, 2, 3, thus reflecting the level of severity in each of the 21 items. The scale was constructed to assess whether depression was to be made as the primary diagnosis.11 The original English version was researched extensively and found to be reliable and valid. The Chinese version of the BDI was used in this study. Studies made by professor Daniel T L Shek of the Chinese University of Hong Kong showed that the Chinese version of the BDI is reliable and internally consistent, and the factors extracted were found to be stable.12 Brief Screen for Depression (BSD): The BSD is a four-item depression screening scale developed by Peter D McLean, PhD, and A Ralph Hakstian, PhD, both professors at the University of British Columbia, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Psychology respectively. The BSD has a high level of sensitivity, being able to discriminate between depressed and normal subjects (99.0% sensitive with a cut-off score of 21), and also between depressed and other nondepressed psychiatric subjects (94.9% sensitive with a cut-off score of 24). In this study we used 25 as the cutoff score as indication of clinical depression, as suggested by the authors.13 Permission was received from Dr McLean to translate the scale into Chinese. Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS): The DAS is a 33-item questionnaire measuring a couple’s adjustment level.14 It provides a global score of adjustment, and subscores of affection, consensus, cohesion, and satisfaction. Research data suggested that below a certain cut-off score the couple is severely maladjusted and divorce is likely. A Chinese version of the DAS was used in this study. Data entry and statistical analysis The GB-STAT for Windows15 statistical program was used for data entry and analysis. Cut off scores for the different levels of depression and for severe marital maladjustment were entered into the program. Percentages of subjects within each level (mild, moderate, severe and extreme) of depression, and percentage with severe marital maladjustment were calculated. Result Descriptive statistics Our sample consisted of 80.5 percent females and 19.5 percent males. More than half were between 35 and 44 years old. Those above 55 were not in this sample. Over fifty-five percent (55.7%) of our sample were married, followed by 34.8 percent who were never married. Compared to the latest population census, the 1996 Hong Kong Population By-census (hereafter 1996 Census), the divorce/separation rate in our sample (6.8%) was 3.6 times higher than the general population (1.9%). All of the subjects had some kind of formal education. Almost sixty-four percent (63.8%) had attained some level of secondary school education, followed by 29 percent who had primary school education. Over seven percent (7.2%) had university education. Compared to the 1996 Census, our sample’s educational attainment appeared to cluster toward the middle – significantly more secondary level, but relatively less primary and tertiary level. Compared to the 1996 Census, our subjects had higher financial responsibility because of its higher household size, but were relatively poorer as reflected by their housing situation and their lower salary. Around thirty-six percent (36.2%) of our subjects had four members in their families, followed by five members (20.2%). Our sample had a significantly higher percentage who rented public rental flats (59.3% in our sample versus 38.5% in the census), but a relatively lower percentage who owned private flats (32.4% in our sample versus 46.9% in the census). Compared to the 1996 Census, our sample had twice as many subjects in the HK$5,000 - $9,999 range (61.8% in our sample versus 31.7% in the census), but less subjects in the upper income range. Almost 78 percent of our sample had income below the median income of HK$9,500 (1996 Census). Sixty-six percent were unemployed for less than one year, followed by 16.3 percent who were unemployed between one year and 23 months. Therefore, unemployment was a fairly recent experience for most of our subjects. Almost thirty-nine percent (38.8%) of our subjects reported that two people were responsible for family expenses, followed by 25.1 percent who were dependent mainly on the spouse. Major hypotheses 1. There was a significant percentage of clinical depression among the unemployed sample: This major hypothesis was supported by both the BDI and the BSD scores. According to the BDI, 33.6 percent (74 subjects) of our subjects had scores that fell within the clinically depressed range. Among these, 10.5 percent (23 subjects) fell within the mild depression range, 15.9 percent (35 subjects) within the moderate depression range, 7.3 percent (16 subjects) within the severe and extreme depression range. (Figure 1) According to the BSD, 29.5 percent (64 subjects) of our subjects had scores that indicated clinical depression. (Figure 2)

The two instruments yielded very similar results, an alarmingly high clinical depression rate of around 30 percent in our unemployed sample. Compared to a comprehensive epidemiological study on mental health in the United States, which reported a 9.5 percent depression rate,16 our sample’s depression rate was three times higher. Although our sample consisted of around 80% female and 20% male, no significant difference in depression was found between female and male subjects, nor among other demographic variables. Detailed analysis of the BDI indicated that 25.5 percent (56 subjects) of the subjects had thought of suicide. Out of these, 21.8 percent (48 subjects) had suicide ideation, but would not attempt it, 3.7 percent (8 subjects) wanted to take their own lives if given the chance. More than half of the subjects (121 subjects, 55%) had disturbed sleep. Out of these, 16.8 percent (37 subjects) had early morning awakening and had difficulty falling back to sleep. 2. There was a significant percentage of severe marital maladjustment among the unemployed sample: The percentage of divorced/ separated subjects in our sample (15 subjects, 6.8%) was 3.6 times higher than those in the 1996 Census (1.9%). Therefore, our sample already had a higher rate of broken marriages to begin with. Furthermore, according to the DAS, 16.4 percent (22/134) of currently married subjects scored within the severely maladjusted range. Therefore, among those subjects who were previously or currently married, almost 25 percent (37/149 subjects, 24.8%) or one of four subjects suffered from broken marriages or severe marital maladjustment. (Figure 3)

Discussion Unemployment and depression

The high depression rate (around 30%) found in this sample was in agreement with Murphy and Athanason’s findings. They wrote, “It is clear that in 14 of the 16 studies [longitudinal studies], there is evidence of a depressed mental health score being associated with unemployment”.18 An earlier study, using the BDI on 51 employed and 96 unemployed bluecollar women, found significantly more depression among the unemployed subjects.19 The findings in this study was a small reflection of Hong Kong people’s mental health problems in recent years. It was reported in 1999 that Hong Kong people suffered greater mental health problems than their American counterparts and were more careless in their work as a result.20 Also, one in five visitors to both public and private clinics were ‘mentally ill’, suffering from depression and anxiety disorders.21 An appeal to professionals Although the unemployment rate has dropped from its record high of 6.3% in April 30, 1999 to 5.5% one year later in April 30, 2000,22 this was still high when viewed historically. This was equivalent to the November 1998 figure when 185,300 persons were unemployed.23 The Government had earmarked an additional recurrent provision of $300 million this year, for launching new initiatives in 2000-2001 to help ease unemployment and encourage lifelong learning.24 These measures, however, do not address the problems of depression and marital maladjustment in the unemployed, as found in this study. Therefore, medical practitioners, clinical psychologists, and social workers need to be sensitive to the high probability of clinical depression and marital maladjustment in their unemployed clients. An editorial in a medical journal in Hong Kong urged fellow physicians to “make every effort to recognise and treat depression adequately because morbidity and mortality from depression can be reduced”.25,26 Diagnosis and treatment need to be in a timely manner, as early intervention affects good outcome. A study of 118 unemployed and 136 employed workers from two similar wood processing factories found impaired mental well-being among the unemployed at six months, but the prevalence of depression and psychosomatic symptoms were higher at 18 months follow-up.27 Thus, the longer the wait the more severe the depression. The long waiting list for public medical and psychological services in Hong Kong is less to be desired. Conclusions Among the 221 unemployed subjects, around 30 percent were found to suffer from various degrees of clinical depression as indicated by the BDI and the BSD scores. In addition, almost 25 percent of those previously or currently married were found to suffer from broken marriages or severe marital maladjustment, as indicated from the demographic information and as measured by the DAS. These alarmingly high rate of clinical depression and severe marital maladjustment in the unemployed calls for proper diagnosis and timely intervention by professionals. Acknowledgments I am grateful to Shek Tan-lei Daniel, PhD, (professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong department of social work), and Mak Ki-yan, MD (private practitioner, and honorary associate professor at the University of Hong Kong, department of psychiatry) who provided valuable academic literature and helpful input toward this study. My agency director, Nora YAU, JP, and development officer, Tang Kwok-wing, offered encouragement and assistance in this project.

References

|

||