|

October 2001, Volume 23, No.10

|

Original Article

|

|

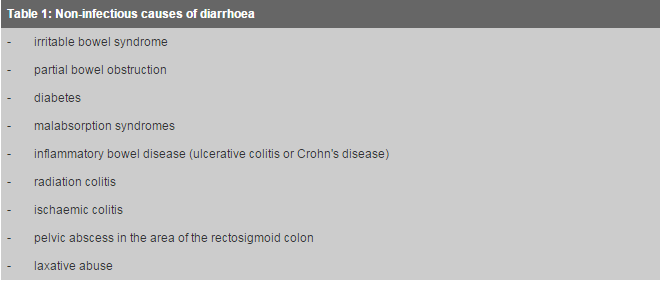

Empiric antibiotics for acute infectious diarrhoeaS S W Chan陳兆華,K C Ng吳景祥,D J Lyon黎安義,W L Cheung張偉麟,T H Rainer 譚偉恩 HK Pract 2001;23:430-437 Summary The vast majority of infectious diarrhoea is caused by viruses, and bacterial gastroenteritis is usually a self-limiting illness. This article discusses the current opinions concerning the use of empiric antibiotic therapy (i.e. starting antibiotics before identification of the responsible pathogen) for infectious diarrhoea. The scientific evidence, including recent local data, and the risks and benefits of this approach are reviewed, to guide practitioners in Hong Kong. Precautions against the widespread use of quinolone antibiotics are emphasised. 摘要 大多數的感染性腹瀉由病毒引起,而細菌性胃腸炎常常是自限性的。本文針對用經驗性抗菌素療法(即在確定致病原之前就使用抗菌素)治療感染性腹瀉的目前的一些看法進行了討論,還對有關的科學証據(包括本地最近的數據)以及本療法的利弊進行了綜述,做為香港執業醫生的指引。本文還強調避免廣泛使用諾酮類抗菌素的應注意事項。 Introduction Infectious diarrhoea is defined as diarrhoea caused by infectious agents. It can be caused by viruses, bacteria or parasites (e.g. giardiasis, amoebiasis), and the pathogen may either be toxigenic, enteropathogenic, or both. Therapeutic decision-making for infectious diarrhoea is a common problem encountered by primary care practitioners. Whilst the mainstay of management for this condition is rehydration or prevention of dehydration, symptomatic therapy, and the prevention of spread of infection,1 there has been an increasing emphasis on the use of empiric antibiotics in recent years.1-5 At the same time, the problem of abuse and misuse of antibiotics has also gained widespread attention in Hong Kong. The standard of "good medical practice" in this area needs to be defined and addressed. This article therefore reviews the scientific evidence and presents the various expert consensus and guidelines concerning the use of empiric antibiotics for adults with acute infectious diarrhoea. The indications, the choice of antibiotic, and the precautions, based on these resources, are discussed. Since the efficacy of empiric antibiotic therapy will vary according to the spectrum of pathogens, which may be different from region to region, the applicability of overseas recommendations in Hong Kong may be questionable. The results of a recent study of the prevalent pathogens in community-acquired gastroenteritis in Hong Kong, and their antibiotic susceptibilities, are reported.6 The development of antibiotic resistant strains of pathogens continues to be of serious concern, and there are definite reservations over the indiscriminate use of empiric antibiotics. The practitioner also needs to be aware of the non-infectious and extraintestinal causes of diarrhoea (Table 1) before considering antibiotics for presumed infectious diarrhoea.

Authoritative guidelines and expert opinions

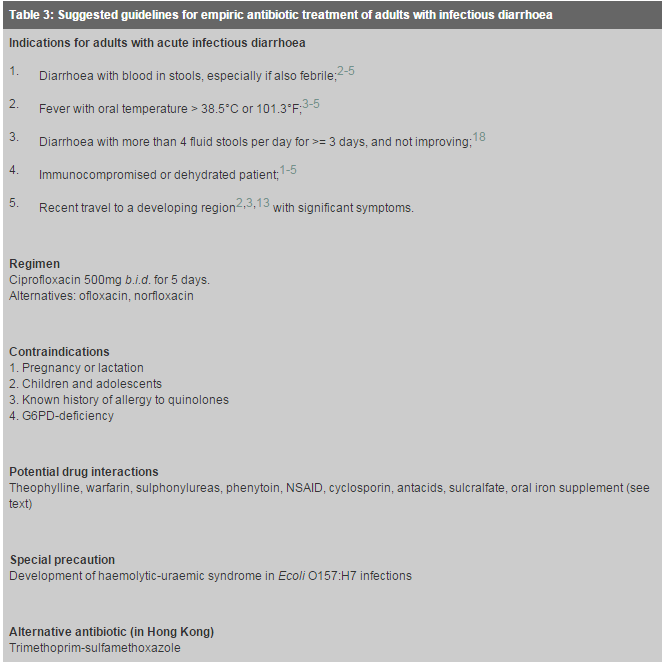

Efficacy and side-effects of quinolones The quinolones are generally effective against all the usual bacterial causes of infectious diarrhoea: Ecoli, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Yersinia, Aeromonas and Plesiomonas, (with the exception of Campylobacter, which will be discussed below). These antimicrobial agents are rapidly bactericidal, they do not influence the normal anaerobic stool flora, and they provide good tissue penetration. They are rapidly absorbed orally, and high concentrations remain in the faeces 48 hours after a single dose, which may account for their potent activity against enteric organisms.11 Quinolones are relatively safe drugs as well. Mild gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, transient liver enzyme derangement, allergic reactions, haematologic abnormalities and rare CNS toxicity have been reported. Neither ciprofloxacin nor norfloxacin should be used in young children or pregnant women, primarily due to concerns about toxicity to growing cartilage, and teratogenicity. When administered concurrently with theophylline, the serum theophylline levels may be increased. The effect of warfarin and the sulphonylureas may be enhanced by the quinolones, whilst serum levels of phenytoin are reduced. There is a possible increased risk of convulsion if quinolones are administered together with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Interaction with cyclosporin may also cause a transient rise in serum creatinine. Antacids, sulcralfate and oral iron supplement all cause significantly decreased absorption of quinolones. Evidence related to the use of quinolones empirically in adults with infectious diarrhoea In our review of literature and in another review by de Bruyn,12 all 6 placebo-controlled, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving empiric ciprofloxacin for the treatment of travellers' diarrhoea13-15 and community-acquired diarrhoea16-18 have demonstrated significant benefits. Three of these trials, the ones with larger sample sizes, and each from a different setting, are presented below for reference.

Ciprofloxacin (500mg b.i.d. 5-day course) significantly reduced the average duration of diarrhoea compared to placebo (29 vs 81 hours), and significantly reduced severity of abdominal cramps by day 2. Cases were included if there was passage of four or more unformed stools per 24 hours, or 3 unformed stools in 8 hours plus one or more additional symptom of enteric disease (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or fever). Empiric ciprofloxacin (500mg b.i.d. for 5 days) shortened the duration of diarrhoea compared to placebo (2.4 vs 3.4 days), and increased the percentage of patients cured or improved by treatment days 1, 3, 4, and 5. For case inclusion, diarrhoea was defined as four or more unformed stools in the 24 hours before presentation or three or more stools in the 8 hours before presentation. Empiric treatment with ciprofloxacin (500mg b.i.d. for 5 days) compared to placebo significantly reduced the duration of diarrhoea (2.2 vs 4.6 days) and other symptoms (fever, abdominal pain, myalgia and vomiting; 1.9 vs 4.3 days). Treatment with ciprofloxacin did not prolong carriage. Cases were included if diarrhoea was more than 4 fluid stools per day for 3 days, without improvement, and with at least one of the symptoms of abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, myalgia, or headache. In all three studies, adverse effects of ciprofloxacin were found to be minimal and self-limiting, and the authors concluded that therapy with ciprofloxacin was well-tolerated. Review of RCTs involving quinolones other than ciprofloxacin shows that 2 trials demonstrated benefits with ofloxacin and 4 trials demonstrated benefits with norfloxacin.19-24 Two RCTs of other quinolones (lomefloxacin and enoxacin respectively) found no evidence of benefit.25,26 Furthermore, in the trial of lomefloxacin, 33% of treated people reported adverse effects, including anaphylactoid reactions, and 18% developed isolates resistant to lomefloxacin.25 The development of Campylobacter isolates resistant to quinolone after treatment was also reported with ciprofloxacin14,17 and norfloxacin.21 Norfloxacin also reportedly significantly prolonged excretion of Salmonella from stool compared with placebo.21 By contrast, placebo-controlled RCTs involving antibiotics other than quinolones had only shown benefits for travellers diarrhoea. These included trials of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole,13,27,28 trimethoprim alone,29 aztreonam,30 and bicozamycin.31 Trials of cloquinol and trimethroprim-sulphamethoxazole in community-acquired diarrhoea did not show benefit.12,26 Reservations against the widespread use of ciprofloxacin Apart from cost considerations, any consideration of antibiotic therapy must be carefully weighed against potentially harmful consequences. These include:

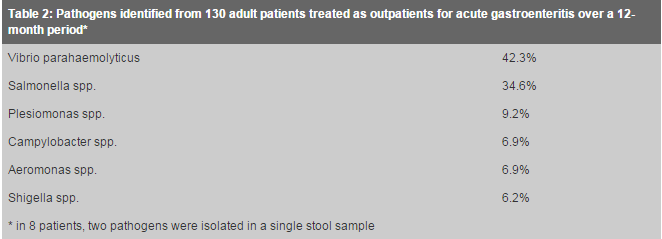

Prediction rules The identification of predictors associated with bacterial cause of infectious diarrhoea may help the clinician in deciding whether or not empiric antibiotic treatment is required. Koplan etal found that the best clinical predictor of a positive stool culture was the combination of persistent diarrhoea (duration more than 24 hours), fever, and either blood in the stool or abdominal pain with nausea or vomiting.39 Cadwgan etal devised a simple scoring system, based on clinical features and C-reactive protein, to predict positive stool cultures in hospitalised patients.40 Schreiber et al found that acute diarrhoea associated with fever >101F, travel history, and the absence of vomiting, was associated with positive stool culture for bacteria.41 Further research on the derivation and validation of clinical decision rules are needed not only to predict bacterial gastroenteritis, but to predict those cases that might benefit from empiric antibiotic treatment. Local data are important to guide the use of empiric antibiotic therapy There may be inter-regional differences in the spectrum of pathogens and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern, which may influence the outcome of empiric antibiotic therapy. Hence any protocol for empiric antibiotic treatment of infectious diarrhoea should ideally be supported by local data. A recent study in Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH) has found that amongst 130 consecutive adult patients with acute gastroenteritis treated as outpatients at the Accident & Emergency Department and with bacterial pathogens identified (Table 2), isolates from 120 (92.3%) stool samples were sensitive to ciprofloxacin.6,42 Isolates from 2 (1.5%) samples were of intermediate susceptibility, and those from 8 (6.2%) samples were resistant to ciprofloxacin.

Salmonella spp. and Shigella spp. All Salmonella isolates in the study were sensitive to ciprofloxacin, and this is consistent with findings from other local studies.43,44 When hospitalised patients and paediatric patients were also considered, an increasing incidence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella cases has been observed in PWH, from 2 cases in the period 1993-1997 to 10 cases in the period 1998 to 2000 (personal communication). As for Shigella, there was a reported trend in increased ciprofloxacin resistance to S.flexneri (0 to 2.1%) from 1986 to 1995 in Hong Kong.45 In our present study, all Shigella isolates were sensitive to ciprofloxacin. The sensitivity patterns ought to be interpreted cautiously. Resistance to quinolones is associated with the presence of several point mutations of the gyrase and other genes. Some mutations will confer resistance to nalidixic acid, but the strains will be classified as "sensitive" to quinolones by standard susceptibility testing criteria such as that of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS).46 However, such strains may have raised minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for quinolones as compared to fully sensitive strains, and clinical failure of ciprofloxacin therapy of invasive nontyphoidal salmonella infection for such isolates is recorded.47 In a recent study in Hong Kong, 6% of S.typhimurium isolated in 1989-1996 were found to have ciprofloxacin MICs greater than 0.12mg/l although they were regarded as "sensitive" when the standard interpretative breakpoint of 1mg/l was used.48 Clinical failure of quinolone treatment has also been reported recently in patients in Hong Kong who were infected by S.typhi isolates that were classified as sensitive to ciprofloxacin, but had ciprofloxacin MICs of >= 0.12mg/l.49 Ciprofloxacin-resistance in Campylobacter isolates In our study of ambulatory adult patients, 7 out of 9 (77.8%) Campylobacter isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin, and this finding is alarming. In many other countries (the Netherlands, United Kingdom, U.S.A.) the frequencies of quinolone-resistance in Campylobacter isolates have been reported to be steadily increasing.36,38,50 All Campylobacter isolates in our study, however, were sensitive to erythromycin. The overall ciprofloxacin susceptibility in Campylobacter spp in PWH decreased from 96.7% in 1993 to 13.2% in 1999, while erythromycin susceptibility generally has been over 90% (personal communication). Continued surveillance of emerging antibiotic resistance in stool pathogens is essential. We recommend that stool should be sent for culture and sensitivity, whenever empiric antibiotics are indicated, and whenever a bacterial cause is suspected. Furthermore, stool should be investigated for C. difficile toxin for hospital-acquired diarrhoea (>3 days after hospitalisation); or if antibiotics were used in recent weeks.3 Parasites should be considered if diarrhoea persists for longer than 7 days, especially in an immunocompromised patient.3 Ciprofloxacin has the best antimicrobial susceptibility-profile locally When susceptibility patterns are considered for pathogens responsible for adult gastroenteritis, ciprofloxacin is the empiric antibiotic of choice in our locality, since isolates from 92.3% stool samples were sensitive. However, this represents data obtained from a study population of emergency department patients, and may not be generalisable to patients in primary care and family practice settings. Our data also shows that out of a total of 138 pathogens isolated over the 12-month period, 122 (87.6%) were susceptible to trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (Septrin), and 50 (36.2%) were susceptible to ampicillin. On this basis, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole may still be considered an appropriate alternative empiric antibiotic in our local setting, especially when ciprofloxacin is contraindicated. Nevertheless, as we have discussed, current expert guidelines and most of the recent major placebo-controlled RCTs demonstrating efficacy of empiric antibiotics in adults are based upon quinolones. Clinical features of Campylobacter gastroenteritis Our study also found that Campylobacter-positive patients, compared to non-Campylobacter patients, presented to A&E with a significantly longer period of abdominal pain (mean, 3.6 vs 1.6 days; P=0.0236). They were also significantly less likely to be dehydrated or require intravenous fluid therapy (P=0.0103). Since all Campylobacter isolates were sensitive to erythromycin, based on these findings, there is some evidence to support the use of empiric erythromycin in patients with infectious diarrhoea, who are not dehydrated, but who present with persistent abdominal pain. The IDSA guidelines do recommend empiric erythromycin for infectious diarrhoea suspected to be caused by Campylobacter.3 Further studies are required to investigate the clinical predictors of Campylobacter gastroenteritis in our locality, and to find out whether such findings can be extrapolated to family practice settings. Conclusion Although the vast majority of cases of infectious diarrhoea are caused by viruses, and those caused by bacteria usually recover within a few days, studies have shown that the use of empiric ciprofloxacin in a subset of adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms generally results in the shortening of the duration of diarrhoea and other symptoms by 1-2 days. A study of the cost-benefit of this "1-2 days" would lead to an interesting discussion and debate which would be beyond the scope of this paper. The benefits of therapy, however, must be balanced against the potential risks. The reservations against the indiscriminate use of ciprofloxacin have been discussed. Empiric ciprofloxacin should be considered only in adult patients with severity of illness satisfying the criteria given by the expert guidelines presented. The inclusion criteria for patients in the RCTs that demonstrated significant benefits with empiric ciprofloxacin may also provide an evidence-based, practical guide. We attempt to summarise essential information from all these resources in our "suggested clinical practice guidelines for adult patients", in Table 3.

S S W Chan, MBBS, FRCSEd(A&E), FHKCEM, FHKAM(Emergency Medicine)

W L Cheung, MBBS(HK), FRCSEd, FHKAM(Emergency Medicine), FHKAM(Community

Medicine)

K C Ng, MBChB, FRCPA, FHKCPath, FHKAM(Pathology)

D J Lyon, MBChB, FHKAM (Pathology), FRCPath

T H Rainer, MBBCh, MRCP, MD, BSc References

|

||