|

December 2002, Volume 24, No. 12

|

Case Report

|

||||||||||||||||

Barrett's oesophagusA C W Mui 梅中和 HK Pract 2002;24:594-603 Summary Barrett's oesophagus is a known complication of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The definition, diagnostic criteria, clinical significance, and management protocol of Barrett's oesophagus are outlined in this article. 摘要 巴雷特食管是胃食管返流病的併發症之一。巴雷特食管的定義、診斷標準、臨床重要性與及治療方法於本文中一一引述。 Introduction Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is increasingly being recognised as an important gastro-intestinal disorder in general practice today. A known complication of GERD is the development of Barrett's oesophagus, which is a pre-malignant condition. While GERD is usually diagnosed clinically, diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus is based on endoscopy and tissue biopsy. Nowadays, a significant proportion of upper GI endoscopies (UGIE) are performed by family physicians. This case report is aimed to arouse interest, as well as to bring out the clinical awareness of family physicians who perform UGIE, on this very important condition. Case history

An eighty-one year-old Chinese male patient was admitted to hospital because of progressive pallor, mental confusion, and haemetemesis. He was a chronic smoker and drank Chinese wine daily. There was no prior history of heart-burn, acid regurgitation, dysphagia, odynophagia, or significant weight loss. His haemoglobin was 4.3gm% on admission and he was transfused. He vomited again on the night of admission and was resuscitated. After vital signs were stabilised with intravenous fluid and blood replacement, upper GI endoscopy (UGIE) was performed. The most prominent feature at UGIE was the presence of multiple irregular patches of pinkish lesions which extended from the oesophageal-gastric junction (EG junction) to mid oesophagus. This is best seen on a "second-look" endoscopy after controlling the oesophagitis first (Figure 1). At the distal oesophagus, an ulcer with an adherent blood-clot was present which signified recent bleeding (black arrow) (Figure 2). A hiatal hernia extending from 34 to 40cm (white arrow) was visible both from the oesophagus (Figure 2) and from the stomach on retroflexion of the endoscope (Figure 3). The aforementioned pinkish lesions at the distal oesophagus stood out more clearly when the oesophagus was sprayed with Lugol's iodine (Figure 4). Biopsies from the ulcer were negative for malignancy, while biopsies from the adjacent pinkish lesion subsequently revealed tall columnar epithelium containing globet cells. This was diagnostic of Barrett's oesophagus. There was no dysplasia or neoplasia in these cells. He was then started on a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), namely omeprazole 20mg twice daily, plus domperidone 10mg three times daily. He was advised to stop smoking and the regular wine drinking. He remained well and was discharged five days later. Since discharge he remained abstinent from cigarettes and alcohol, and was compliant with medication. Subsequent follow-up visits revealed absence of GI symptoms or anaemia. Four months later, his omeprazole was decreased to 20mg daily while the domperidone dose remained unchanged. A repeat UGIE two years later, while he was on an equivalent PPI maintenance regimen, revealed the persistence of Barrett's oesophagus as well as erosions at the distal oesophagus (Figure 5). The dose of his PPI was subsequently doubled, despite the absence of symptoms. In summary, the salient features of this case history are that the patient had been entirely asymptomatic prior to his hospital admission, the presentation of his Barrett's oesophagus as massive haemetemesis, the absence of dysplasia in the oesophagus, and the failure of a conventional dose of PPI to prevent the development of oesophageal erosions. Discussion Evolution of the definition of Barrett's oesophagus Norman Barrett was a British Cardio-thoracic surgeon, who in 1950 first reported the presence of columnar epithelium in the distal oesophagus, which he erroneously thought represented an intra-thoracic part of the stomach.1 This misconception was subsequently rectified in 1953.2 Since then the lesion has been recognised to be due to metaplasia of the normal squamous epithelium of the distal oesophagus to columnar epithelium, as a result of chronic acid exposure (as well as exposure to other toxic matters in the refluxate, such as bile). Thus Barrett's oesophagus was originally defined by the presence of columnar epithelium in the distal oesophagus. Histologically, several metaplastic columnar cell types are recognised at the distal oesophagus due to acid reflux:

It is now generally agreed that only the intestinal type of metaplasia is pre-malignant. Anatomically, intestinal metaplasia can be present in some other similar conditions in the region of the distal oesophagus, namely Intestinal Metaplasia At the Gastro-oesophageal junction (acronymed "IMAGE", also known as Junctional Intestinal Metaplasia), and intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia (Gastric Carditis). These conditions can occur without endoscopically evident Barrett's oesophagus being present. Such conditions are demographically different from Barrett's oesophagus.3 Therefore, in diagnosing Barrett's oesophagus, the endoscopist should take care to take oesophageal biopsies above the GEJ, to avoid over-diagnosis by including intestinal metaplasia due to IMAGE. It is preferable to control oesophagitis first before biopsy, as oesophagitis may mask the typical endoscopy features of Barrett's oesophagus and also make histological interpretation of dysplasia difficult. Some experts4 advocate 4 quadrant biopsies at 4 cm intervals to minimise "sampling error", but such guidelines are not yet universally adopted in practice. Barrett's oesophagus longer than 3cm is designated "long segment" Barrett's oesophagus, those less than 3cm designated "short segment" Barrett's oesophagus. Previously thought to have less malignant potential in the short segment variety, it is now known that both types have the same malignant potential.5 Thus such distinction is now disputed as being redundant. The new proposed definition4 by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) of Barrett's oesophagus is "a change in the oesophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognised at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy". Why is it important to diagnose Barrett's oesophagus The potential dangers of Barrett's oesophagus include ulcerations and haemorrhage, as reported in this case. In one reported series, the incidence of discrete ulcers at the Barrett's oesophagus was 46% and the incidence of bleeding from these ulcers was 79%.6 Peptic stricture is another known complication. The overall complications of GERD appear to be much more common in whites than Asians.4 The greatest concern (and interest) of Barrett's oesophagus is its potential to progress to adenocarcinoma. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing in incidence in the west and is now even more prevalent than oesophageal squamous carcinoma in the USA. It is estimated that about 20% of the US population has GERD and 10% of them eventually develop Barrett's oesophagus. The incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett's oesophagus in two recent large scale studies in the USA were found to be 0.35% and 0.48% respectively.8,9 Carcinogensis The metaplastic epithelium of the Barrett's oesophagus can undergo change to become dysplastic, which is a further step towards transformation to adenocarcinoma. Dysplasia is divided into low grade and high grade. Both dysplasia and its grading in the biopsy samples should be made according to established pathology criteria.10,11 High grade dysplasia carries the highest cancer incidence and is as high as 20 to 25%.12 Epidemiology Chronicity and the male sex are the most important cancer risk factors. There is a family aggregation of Barrett's oesophagus and Barrett's adenocarcinoma. A positive family history of Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma increase risk by 12 times in first and second degree relatives.13 There is also a racial predilection. In the Western community, such cancers occur 6 times more in whites than non-whites,14 which high-lights a genetic predisposition of this disorder. In the Asia-Pacific region, the incidence of Barrett's oesophagus is already reported to be on the rise in Taiwan, which is thought to be partly related to westernisation of the diet.15 Do "non-whites" really have less cancer predilection in Barrett's oesophagus in Hong Kong than Caucasians? It is hoped that our own experts in large institutions and/or specialised centres would look into the regional prevalence of this disorder and furnish us with local statistics on Barrett's oesophagus and its cancer incidence, based on which we may formulate our own surveillance strategy. Treatment As Barrett's oesophagus is a complication of chronic GERD, most of these patients will need treatment of GERD per se. The treatment is summarised as follows:

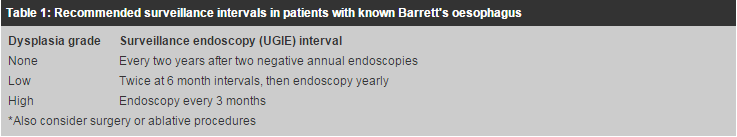

1. Life style adjustment In general, the evidence in support of such advice is not strong, and even conflicting at times. In fact the global consensus of experts judged that these measures were of such low efficacy that they were rejected as a primary therapy for all patient subgroups.16 Nevertheless this advice has the benefit of being easily dispensed (by doctors), cost free, and help to promote a healthier life style in general (however do not forget that your patient, as well as his/her bed partner, may slip down a bed with its head elevated, and a foot-board may be well-heeded advice!) 2. Medical treatment Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are now the main-stay of treatment for GERD. To ensure healing of oesophagitis, it is important to give a sufficiently large dose to maintain the intra-gastric pH to above 4 for over 12 hours. PH is a measure of hydrogen ion activity on a log scale: with pH=1, the acid concentration is 100mmol/L, with pH=2, the acid concentration is 10mmol/L, with pH=3, the acid concentration is 1mmol/L, with pH=4, the acid concentration is 0.1mmol/L, and with pH=5, the acid concentration is 0.01mmol/L. Evidently, when pH is >4, the stomach is almost achlorhydric! In one study, taking omeprazole 20mg once daily orally, a pH=4 for over 12 hours is achieved in only 65% patients.17 Dosage consideration is illustrated in this case report, whereby the patient taking a conventional "maintenance" dose of PPI had failed to achieve complete healing of oesophageal erosions on endoscopy follow-up, even though he had remained symptom free. Adequacy of dosage can be assessed with endoscopy surveillance or with 24-hour ambulatory pH studies, if needed. H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) such as famotidine, and pro-kinetics (drugs which stimulate GI transit) such as domperidone (motilium), are also of benefit for GERD but the efficacy has been repeatedly proven to be inferior to PPIs. Alginic acid (Gaviscon) is an over-the-counter medication which when ingested reacts with gastric acid to form a gel, and floats on the surface of gastric content to act as a mechanical barrier to reflux into the oesophagus. It has been proven to be useful. 3. Surgical treatment Surgical methods are available to reduce acid-reflux. The classical Nissen's fundo-plication is an open operation to tighten the EG junction. Laparoscopic procedures are now available. Endoscopic suturing procedures, such as Endoluminal Gastro-plication using the Bard EndoCinth system, are also being developed and perfected, and serve the same purpose. By replacing a surgical operation by a less invasive procedure, endoscopy techniques enable the patient to undergo the procedure on an out-patient basis, and to return to work the next day. A successful operation may reduce acid reflux sufficiently to obviate the use of maintenance drugs, and offer patients an alternative option to chronic medication. Over-zealous suturing may lead to excessive narrowing of the EG junction leading to dysphagia or difficulty in belching. Despite its efficacy in controlling oesophagitis, PPIs have not yet been documented conclusively to cause regression of Barrett's oesophagus or to prevent its progression to adenocarcinoma.18 Likewise, anti-reflux surgery has not been consistently proven to regress Barrett's oesophagus.19 4. Other treatment modalities Other treatment modalities include oesophageal ablative procedures that cause "re-injury" of the metaplastic mucosa by laser, electric coagulation, or heat probe in the hope that the regenerated mucosa will revert to the normal squamous epithelium. Photo-dynamic therapy is also under investigation. Combination methods, such as high-dose PPI plus multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), have been investigated and show promise.20 5. Surveillance treatment The principle of disease surveillance is to monitor patients at risk at regular intervals in the hope of diagnosing the disease at an earlier stage, so as to institute more timely treatment. The frequency of examinations in a surveillance program is dictated by the incidence of the disease itself. In the case of Barrett's oesophagus, endoscopic surveillance is aimed at detecting cancer transformation. The cancer incidence in Barrett's oesophagus was previously thought to be around 1% per year. The suggested endoscopy interval then was yearly. As mentioned earlier, its true incidence is now thought to be much lower. Therefore the suggested endoscopy intervals are correspondingly lengthened. More frequent endoscopies are advised in patients with dysplasia, especially in the high grade variety, due to the higher cancer incidence in this subset. The ACG guideline on the surveillance schedule for Barrett's oesophagus4 is summarised in the following Table 1.

Conclusion GERD is frequently encountered in general practice. Most of the patients can be diagnosed and treated on clinical grounds. However, UGIE should be considered in special sub-groups as outlined above. Doctors who perform UGIEs should be aware of Barrett's oesophagus, and should be able to take biopsies from proper sites for confirmation when it is present. They should also remember to scrutinise biopsy reports for any dysplasia, duly inform their patients if dysplasia is present, and to suggest for all patients with Barrett's oesophagus proper follow-up schedules.

A C W Mui, MBBS(HK), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Glasg), FHKAM(Med)

Specialist in Gastroenterology & Hepatology Correspondence to: Dr A C W Mui, , Room 1505, Sino Centre, 582-592 Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong. References

|

|||||||||||||||||