|

April 2007, Volume 29, No. 4

|

Original Articles

|

Pattern and determinants of Traditional Chinese Medicine use for upper respiratory tract infection among adults attending primary care clinicsT K Cheung 張子祺, William C W Wong 黃志威, Nicola Robinson HK Pract 2007;29:134-144 Summary

Objective: (1) To explore the pattern of Traditional Chinese Medicine

(TCM) use for Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (URTI); and, (2) to identify the

determinants associated with such health-seeking behaviours.

Keywords: Upper respiratory tract infection, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hong Kong, primary care 摘要

目的: (1)探討傳統中醫藥在治療上呼吸道感染的應用模式(2)鑒別該種求醫習性的決定性因素。

主要詞彙: 上呼吸道感染、中醫藥、香港、基層醫療。 Introduction Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) is one of the commonest conditions encountered in primary care setting.1,2 Most URTI are self-limiting. Western medicines prescribed are mainly for symptomatic relief, although their effectiveness is often inconclusive.4,5 Studies have also shown that antibiotics are ineffective and probably unnecessary in most cases.6-9 On the contrary, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners believe an illness is due to disturbance of balance within the body. The treatment approach is thus to restore the balance of energy in the body.11,12 In fact consulting TCM practitioners is very common among Hong Kong residents.3,12,13 According to the Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, about 22% of medical consultations in Hong Kong are provided by Chinese medicine practitioners.14 The use of different types of TCM preparations (not limited to formal TCM visits) by the public is probably even higher than that quoted by World Health Organization which estimated that the use of traditional herbal preparation accounted for 30-50% of total medicinal consumption in China.15 Despite the support of TCM development in Hong Kong by the government, the utilization pattern and determinants related to use of TCM for common conditions such as URTI among our primary care patients are not readily available. This study aims to explore details of TCM use for URTI and to identify any possible determinants predicting such health-seeking behaviours. Using URTI as an example, the results from this study are expected to increase the understanding of the role of TCM and how it interacts with other health services among our primary care patients. In this study, TCM is defined as any traditional knowledge, skills and practices that is recognized and accepted by the Chinese community in the maintenance of health and treatment of diseases.15 It is developed and handed down from generation to generation in the Chinese community. It includes Chinese herbs, herbal pills, "healing soup" (i.e. soup made with the purpose to relieve discomfort or promote well being of the body), acupuncture, scraping, combustion (cupping) and reflexology.15 Methods Study design Anonymous questionnaires were distributed to every patient over the age of 18 years old that had fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria, irrespective of their intention of visit to the clinic. Three private general practice clinics were included in the study: one located in a newly established public housing estate where the population tended to be younger; one near a busy commercial district where the population served was mainly working class and office people; and, the third one located in private housing area. The expected expenditure per consultation in the three clinics was similar. Training on the approach and procedures of the study was offered to all participating doctors to ensure standard. Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria Subjects were included if (1) they had URTI symptoms within the previous 2 months; (2) age 18 to 59; (3) were Hong Kong residents; (4) were able to complete the questionnaire; and, (5) could provide informed consent. They were then invited to participate and complete the questionnaires. URTI was defined using the definition in the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2).16 Participants were asked to report their symptoms accordingly at the beginning of the questionnaire for verification.17,18 Patients who had attended the clinics for follow-up or had been asked to participate in the study before were excluded in order to make sure each person only responded and completed one questionnaire. Sample size Different studies on the use of complementary and alternative medicine (including TCM) in other countries showed that the prevalence ranged from 20% to 40%.19-22 Using the averaged prevalence of 30% with 80% power and alpha at 0.05, the sample size required for this study was estimated as 360. Analyzing methods Data was processed using SPSS 14 for PC. Chi- square test was used to test possible associations between TCM use and factors that might account for the use. Statistically significant independent variables such as age, sex, number of URTI episodes were initially identified by binary logistic regression. Multiple logistic regression analysis was then carried out for those variables with p<0.05 in simple logistic regression in order to determine the possible independent predictors of TCM use to treat URTI. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results Demographic characteristics 414 patients were invited to participate from 15 February - 28 April 2006 and totally 399 questionnaires were distributed (response rate=96.4 %). There were 381 (completion rate=95.5%) returned questionnaires for analysis, with 203 male (53%) and 176 female (46%) respondents. 18 questionnaires were excluded as no written consent was obtained. The median age group of our sample was 18-29 years old. Around 56% of respondents had secondary education and more than 23% had a degree or higher level of education. Median monthly salary was HK$8000-11999. This was comparable to the average salary of working class people in Hong Kong.23 (Table 1)

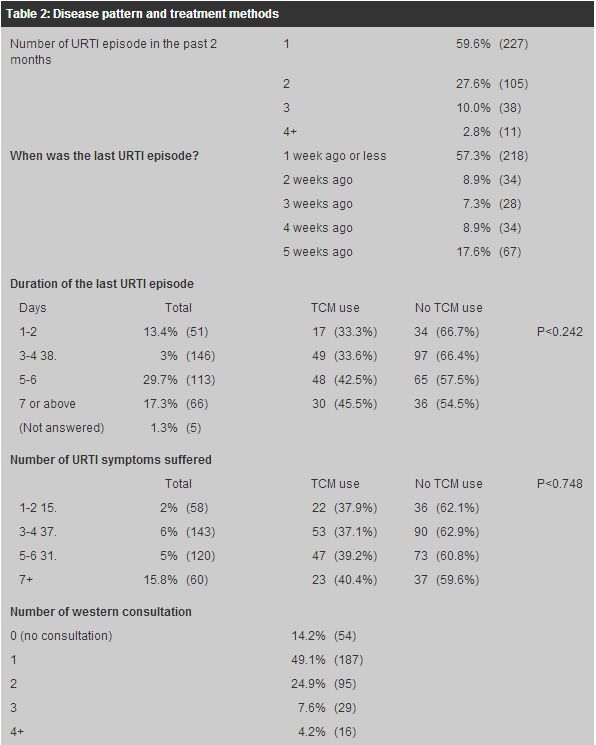

Disease and consultation pattern Around 85% of our respondents had at least one consultation with a western doctor for their previous URTI (49.1% had 1 consultation; 24.9% had 2 consultations). (Table 2) 38.1% of all respondents reported to have used TCM for that episode of URTI. The proportion of those having western consultation was similar among patients having TCM treatment or without TCM use.

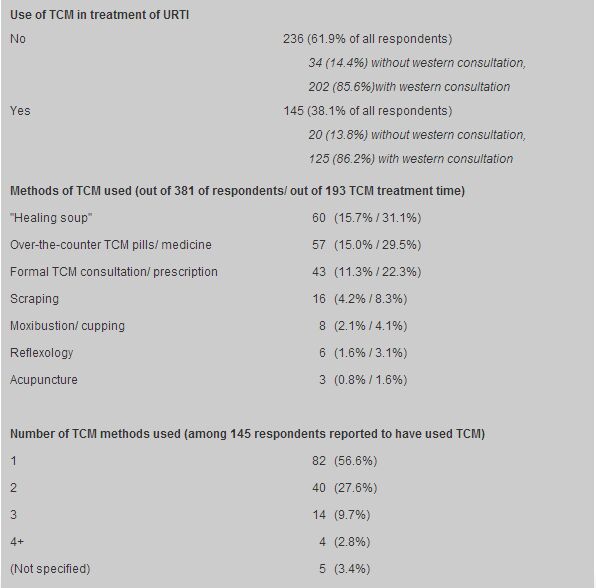

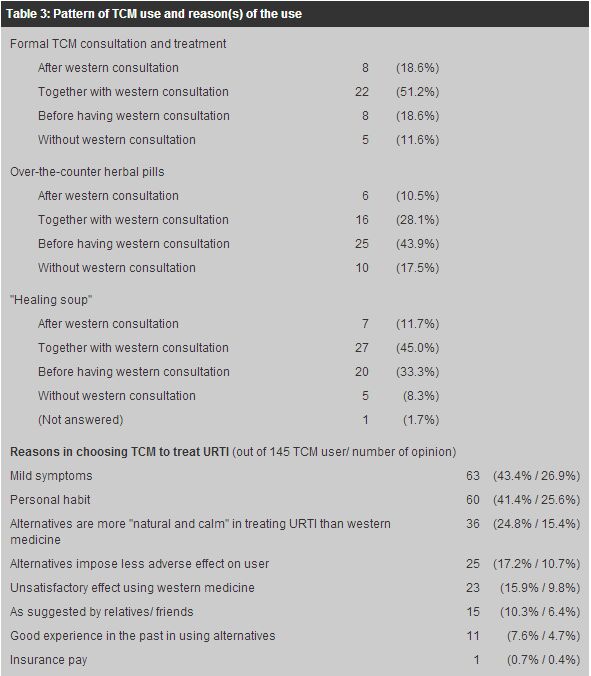

Pattern of TCM use Of the respondents 38.1% had tried at least 1 type of TCM treatment methods and 15.0% of them had tried over-the-counter herbal pills. (Table 2) About 15% made "healing soup" by themselves which could be regarded as a form of self-help diet therapy in local culture. 11.3% reported to have formal TCM practitioner consultations and treatment. Just over half (51.2%) of respondents had tried formal TCM treatment and 45.0% of respondents who tried "healing soup" did so at the same time when they were using western medicine. Respondents reported using over-the-counter herbal pills tended to try these before having a western doctor consultation (43.9%). (Table 3)

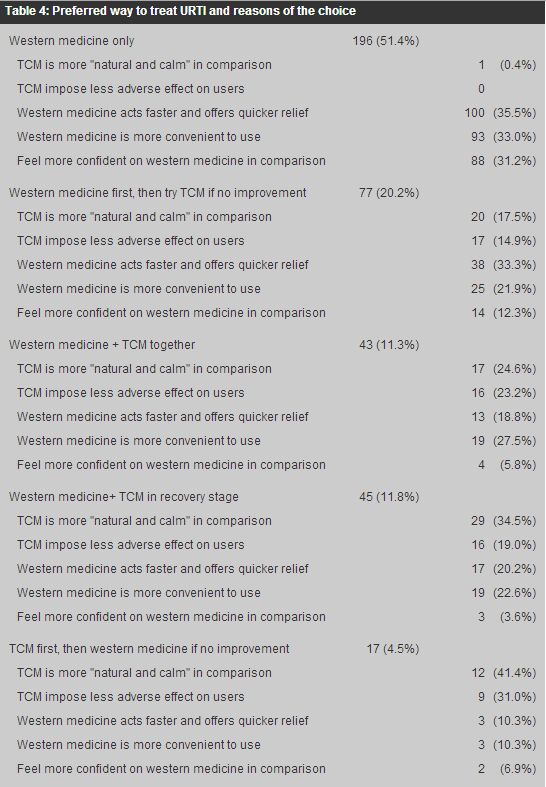

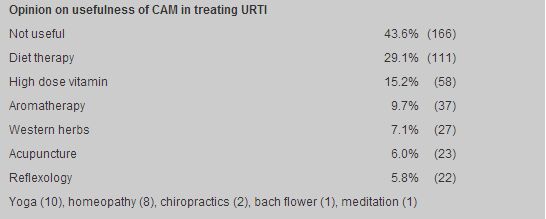

Use of TCM was more common among older people (18-29 age group: 27.8%, 50-59 age group: 48.1%, p< 0.007). (Table 1) However, neither the number of reported symptoms nor any particular symptom was significantly related to TCM use. Salary and educational level was not shown to have significant association neither. Of those who used TCM for that URTI episode 43.4% claimed to have only mild URTI symptoms and around 25% of the patients perceived TCM having the advantage of being more "natural, calm and impose fewer side effects". (Table 3) When the respondents were asked whether they would like to use TCM or western medicine to treat URTI in an ideal situation, 51.4% would choose western medicine; 20.2% of respondents would choose western medicine but would try TCM if western medicine was not helpful. (Table 4) Around 23% of respondents would use western medicine and TCM either at the same time (11.3%) or use TCM in the recovery stage of their illness (11.8%). A total of 43.6% of respondents thought that all other listed Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM; a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine24) was not useful in treating URTI. Around 29.1% and 15.2% believed diet therapy and high dose vitamins respectively were helpful. Less than 10% of respondents believed aromatherapy had played a role in treating URTI.

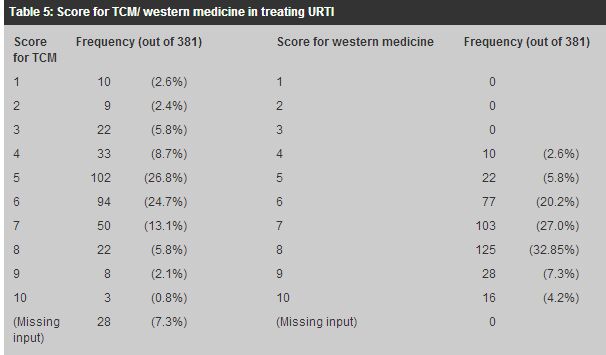

Satisfaction for TCM and western medicine Respondents were asked to express their feeling in terms of scores towards treatment of URTI by TCM or western medicine (score 1-10, 10 being excellent). Most respondents gave 6 to 8 points to western medicine (80.1%). Scores for TCM in treating URTI were diverse with around 60% or respondents giving a score 7 or 8 (Table 5).

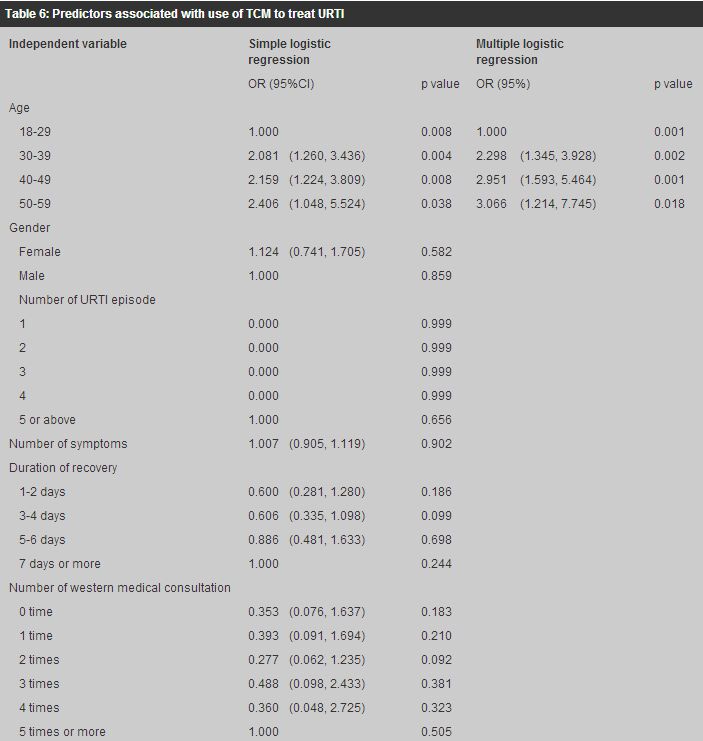

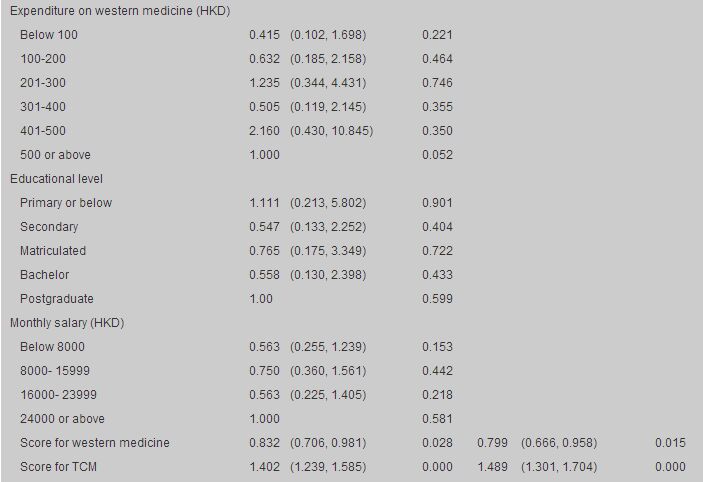

Correlation pattern From binary logistic regression, age, scores for western medicine and scores for TCM were shown to be independent predictors associated with TCM use in treating URTI. (Table 6) For instance, people in the age group 30-39 was twice as likely to use TCM (OR=2.298; 95%CI=1.345, 3.928; p=0.002) in comparison to those in the age group of 18-29 (OR=1.000; p=0.001). For people aged 40 or above, the use of TCM to treat URTI was even higher (age 40-49: OR=2.951, age 50-59: 0.001; OR=3.066, p=0.018).

People that gave higher score for TCM were more likely to use TCM (OR=1.489; 95%CI=1.301, 1.704; p<0.001). People gave a higher score for western medicine were less likely to use TCM during an URTI episode (OR=0.799; 95%CI=0.666, 0.958; p=0.015). Discussion Previous local studies13,25 have shown that people suffering from URTI might not practice any self-medication before western consultation, but we found that the use of TCM during URTI played a significant role. More than one-third of the patients, who attended primary care clinics, practiced at least one kind of TCM treatment when they suffered from URTI. Most however chose to try their own TCM remedies instead of consulting a TCM practitioner. As compared to the use of CAM in the United States, the percentage of patients seeking care from a licensed practitioner before using non-conventional medicine was similar (around 12%).24 The approach was different in that most TCM users from Hong Kong would try "healing soup" and over-the-counter TCM pills by themselves. Unlike the use of CAM in the United States,24 the use of TCM in Hong Kong seems to be similar among people with different educational levels or the severity of the URTI episode (duration of the URTI, number of symptoms) although subjective mild symptoms was one common reason among our respondents to use TCM. Perceptions by the patient rather than objective severity of the disease or underlying background about the disease seem to affect the choice of treatment and this fits well with the prediction in Health Belief Model. However, the older the patient, the higher likelihood is of using TCM to treat URTI. Previous experience or knowledge with TCM helps to assess risk in the formation of one's perception. Its unpopularity among younger people may be explained partly by the westernization of the community and partly relates to the fact that western medicine is relatively easier to access and effects are perceived to be more rapid. However, with the public awareness of other treatment methods through the efforts and supportive attitude of government and health food industry, the use of other forms of treatment (not limited to TCM) will be expected to grow at a fast pace in the future. Nonetheless the use of TCM in general was not different among male and female (36.5% vs. 39.2%, p<0.167) and unlike the use of CAM in the United States female was not shown to have greater tendency to use TCM in this study.24 Similarly the lack of association between education level and TCM use was different to that observed in the west.26-28 Mild symptoms and personal habits accounted for more than half of the reasons why people tried TCM for their URTI. Most still prefer to use western medicine for their URTI because western medicine works faster and offers quicker relief, more convenient and people still feel more confident on western medicine in comparison.13,25 Yet only slightly more than half of people will use western medicine alone to treat their URTI if they are given the choice to use TCM. Most prefer not to use TCM alone initially. These probably reflect people's general idea about the different nature of two streams of treatment. It is quite possible that different types and approaches of TCM are also viewed and handled differently. The use of TCM herbs or herbal pills for those patients concurrently taking western medicine is also alarming. Possible drug-herbs interactions may need to be considered. Such consultation behaviour should be addressed especially during consultation with potential TCM users. This can be initiated by the doctor as patient may not voluntarily talk about the use of other treatment methods.28-30 Western doctors should therefore be equipped with some basic TCM knowledge to facilitate such consultations. Many respondents did not believe in the usefulness of alternative medicine in treating URTI (43.6%). Among those who accepted the role of CAM in treating URTI, most chose diet therapy as the option. This may reflect that local people are lack of exposure to the range of CAM. Mind-body medicine is common as a branch of CAM in the United States24 but is not reflected in this study in Hong Kong. Limitations The fact that this study only focuses on the use of TCM among patients attending primary care clinics may not be representative of the general picture of TCM use in Hong Kong. People who choose to have a formal TCM consultation for URTI may not even attend primary care clinics. The designated clinics in fact may not represent the situation for Hong Kong as a whole. Inclusion of more private and public clinics in different districts may be warranted in the future study. The involvement of TCM practitioner may provide a broader picture as this would capture those patients who habitually seek help from TCM practitioner and do not consult western doctors for minor ailments. There is possibly some overlapping of TCM use as on-going health promotion practice and as ailment during a disease episode. The differentiation is emphasized in the questionnaire but still subject to report bias. The prevalence of CAM use in general appears to be different for different diseases. People tend to treat their musculoskeletal conditions or chronic illnesses with CAM.24 URTI as a common acute disease probably reflect only a specific part of the attitude and behaviour among local people towards TCM or even CAM in wider context of health seeking. Conclusion Use of TCM to treat URTI among adults attending private clinic is not uncommon. TCM is more popular among older patients. However, pattern of use of different TCM entities are different. Primary care doctors should be aware that patients may apply TCM treatment according to past experiences rather than in a formal health setting. People tend to practice TCM treatment together with treatment offered by physicians for their URTI. Doctors are advised to discuss the issue of TCM use with potential TCM users during the consultation. Meanwhile young people are less likely to use TCM in treating URTI as shown but the attractive idea of using more "natural" agents rather than western medicine and the growing popularity of supplement and health food use may alter the situation. In the changing attitudes towards health, doctors trained in western medical schools should be equipped with some basic knowledge of TCM so that they are aware of the health-seeking behaviours of the community and advise appropriately. Acknowledgements Profound thanks to Ms Catherine Cheung who offered support for the data analysis and statistics interpretations; and to Dr K L Cheung and Dr K C Lam in assisting questionnaire distribution. Key messages

T K Cheung, MBChB, MFM

Associate Consultant, William C W Wong, MBChB(Edin), DCH, FRCGP Assistant Professor, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Nicola Robinson, PhD, BSc (Hons) MFPHM, MBAcC Professor of Complementary Medicine, Centre for Complementary Healthcare and Integrated Medicine, Faculty of Health and Human Sciences, Thames Valley University. Correspondence to : Dr T K Cheung, Department of Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 4/F School of Public Health, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong.

References

|

|