|

June 2009, Volume 31, No. 2

|

Original Articles

|

Control of influenza A outbreak in old age home residents in Hong Kong: pharmacological and non-pharmacological approachesKa-chun Chiu 趙嘉俊, Leung-wing Chu 朱亮榮, James K H Luk 陸嘉熙, Alice Choi 蔡淑敏 Summary

Objective: To describe a prompt response strategy from the Centre

for Health Protection (CHP) and the Community Geriatrics Assessment Team (CGAT)

in the control of influenza A outbreak in old age homes (OAHs) and to investigate

the clinical outcomes of residents who did not receive oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis.

Keywords: Influenza, outbreak, institution, nursing home, oseltamivir 摘要

目的: 介紹由衛生防護中心和社區老人評估小組為監控安老院舍甲型流感爆發制定的快速應變計劃,並且研究未接受奧斯他韋預防藥物的院友之臨床結果。

主要詞彙: 流感,爆發,公共團體,安老院舍,奧斯他韋。 Introduction Influenza occurs in Hong Kong throughout the year with two seasonal peaks in February/ March and July/ August.1 The commonly circulating influenza viruses are influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2) and influenza B. Influenza is a highly infectious viral disease. It causes acute illness of the respiratory tract and is usually self-limiting within a few days. Major complications may develop especially in the elderly. These include pneumonia, acute bronchitis, otitis media, myocarditis, pericarditis, encephalitis, Guillain Barre Syndrome, transverse myelitis and delirium.2 This may cause an upsurge of health care services utilization, such as general outpatient attendances, Accident & Emergency attendances and hospitalization during seasonal peaks. Elderly people living in old age homes (OAHs) are characterized by frailty, physical and mental dependency because of the multiple comorbid diseases. They, in general, have reduced immunity and are susceptible to infectious diseases. A local paper reported that the rate of influenza and its complications increased in private OAHs (compared to government subvented OAHs) and in OAHs with a high proportion of residents with pulmonary disease.3 An overseas study found that OAHs with a larger resident population are at risk of influenza outbreak.4 OAHs in Hong Kong are usually crowded and this may increase the risk of infectious disease dissemination. Despite the free influenza vaccination provided to elderly residents in OAHs in Hong Kong and the high vaccination uptake rate, influenza infection still occurs in OAHs owing to yearly drifts or shifts in the influenza strains. Influenza outbreaks in OAHs are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly. An effective management strategy in controlling outbreaks is therefore important to reduce the negative impact of the disease on elders living in OAHs. At present, whenever there are influenza outbreaks in OAHs in Hong Kong, the Centre for Health Protection (CHP) will investigate and manage the outbreak. They will perform site visits and provide oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis to residents and staff. General health advice including good personal hygiene, good ventilation, use of face mask, minimization of group activities, symptom monitoring, isolation/cohort of sick residents and increase frequency of disinfection would be offered by CHP. The OAH is put under medical surveillance. At the same time, the Community Geriatrics Assessment Team (CGAT) operated by the Hospital Authority will be notified. The Hong Kong West CGAT has set up a prompt response team, the Combat Influenza-like-illness Team (CILIT), in 2004 to provide early clinical management of elders living in OAHs with comfirmed influenza. The CILIT, which consists of a nurse and a specialist geriatrician, would perform on-site visit to treat symptomatic residents. Since oseltamivir is relatively contraindicated in subjects with renal impairment, a proportion of residents in OAH would not be able to receive the prophylaxis or treatment. It is not known whether this group of residents who were not offered chemoprophylaxis would deteriorate in terms of the development of influenza like illness (ILI), hospitalization and mortality. Therefore, the objectives of the present study are (1) to describe a prompt response strategy in the control of influenza outbreak in the OAHs in the Hong Kong West Cluster of Hong Kong; and (2) to compare the characteristics and clinical outcomes of elderly residents in OAHs who did and who did not receive oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis during an influenza outbreak. Method Subjects Elderly residents living in OAHs with influenza outbreaks declared by the CHP during the period of 1st April 2007 to 31st July 2007 were included. Residents less than 60 years of age were excluded. The case definition for ILI was adopted from CHP, which was the presence of fever of more than 38°C together with either sore throat or cough on or after a particular date (which was 4 days before the onset of the first case). Study design This was a prospective study to describe the strategy in the control of influenza outbreaks in OAHs of Hong Kong and its outcome. Data collection A pre-designed structured data collection form was prepared. The information below was collected by an experienced geriatric nurse who was assigned to the corresponding OAH and who had experience in community geriatric care:

Outcome measures

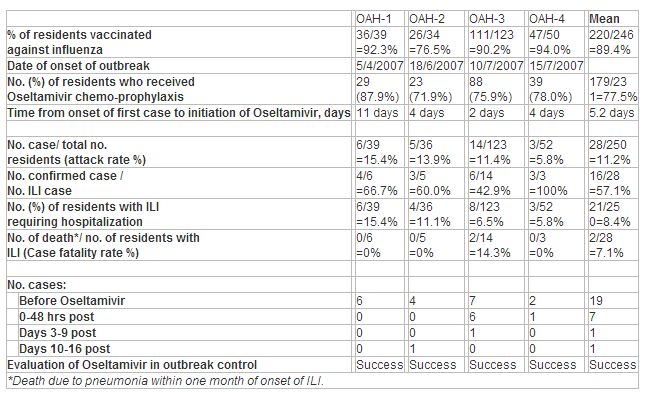

An outbreak was defined as successfully controlled if no more than two cases of acute respiratory illness were observed from Day 3 to Day 9 after the initiation of prophylaxis (week 1) and no more than two cases between Days 10 and 16 (week 2). This definition was previously defined by Bowles SK et al when their team studied the influenza outbreaks in Ontario nursing homes during 1999-2000.5 Statistical analysis Descriptive analysis was used to study the ILI subjects and the whole population under study. Chi-square test (or Fisher exact test where appropriate) was used to compare the categorical variables between the ILI group and the non-ILI group, and between the Oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis group and the No-oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis group. The independent sample t-test was used to compare the continuous variables between the ILI group and the non-ILI group, and between the Oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis group and the No-oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis group. A p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Results Demographic and clinical features of residents under study(Table 1) From April to July 2007, 4 influenza outbreaks occurred in 4 private OAHs in the Hong Kong West cluster. All 4 outbreaks were caused by influenza A virus. Excluding those who were less than 60 years of age (only 4 residents), there were 250 residents residing in the OAHs at the time of the outbreak. The mean age of the 250 residents was 83.9 years (ranged from 62 - 104), 78.8% were female. 45.6% of them were immobile (chairbound or bedbound). Each resident had a mean of 3.6 comorbid diseases. 222 (90.4%) had at least one of the following diagnoses: hypertension, heart disease, lung disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease or dementia. Of the 246 residents whose vaccination status were known, 220 (89.4%) had received influenza vaccine in the winter of 2006. The vaccination rate of staff was 50% (9/18) in one OAH and was not known in the other three.

Table 1: Demographic and clinical features of 250 residents in the 4 old age homes with influenza A outbreak

Influenza virus strain during the outbreak All 4 outbreaks were due to influenza A/H3N2, the predominant circulating strain of influenza during the 2006/2007 season in Hong Kong. Resident attack rate varied from 5.8% to 15.4% (Table 2). Overall, 28 residents met the case definitions of ILI. Of these, 16 had nasopharygeal aspirates submitted for testing and all were positive for influenza A (6 by both viral culture and antigen testing; 6 by antigen testing only and 4 by viral culture only). No other viruses were isolated. Control of influenza outbreak in OAH and its outcome(Table 2 and Figure 1) CHP and CGAT were notified during the outbreaks when 19 residents in the 4 old-age-homes had already developed symptoms of ILI. At the time of notification, there were 13 residents admitted to hospitals because of ILI symptoms. One of them subsequently died of pneumonia within one month of admission. The mean time from onset of the first case to notification to CHP and CGAT were 3.5 days. On-site assessment by CHP and CGAT was performed in these OAHs and oseltamivir prophylaxis or treatment was initiated at a mean of 5.2 days (range 2-11) after the onset of the first case. Of the remaining 237 residents who were assessed by CHP or CGAT, 2 were advised admission to hospital because of their unstable condition (they were subsequently confirmed to be influenza A cases in hospital), 3 received treatment doses and 178 received prophylactic doses of oseltamivir. 54 residents did not receive oseltamivir because of a relative contraindication.

Table 2: Summary of influenza A outbreaks in the 4 old age homes (OAHs)

After the start of oseltamivir prophylaxis or treatment in the OAHs, symptomatic illness developed in 9 residents (6 had received oseltamivir prophylaxis) and 6 of them required hospitalization. In 7 of 9 instances, the onset of illness was within 48 hours from the start of prophylaxis (Table 2). Of the 6 hospitalized residents, 4 were confirmed influenza A cases in which one died of pneumonia within one week of admission. The overall ILI attack rate during the influenza outbreaks was 11.2% and hospitalization rate was 8.4%. 15 residents out of 250 (6.0%) were admitted to hospital before the intervention from CHP and CILIT and the hospitalization rate was reduced to 2.5% (6/235) after the implementation of infection control measures in the OAHs. The overall case fatality rate was 7.1% (2/28). Both cases died of pneumonia as a complication of ILI. As shown in Table 2, the number of ILI cases decreased dramatically after the start of oseltamivir especially from day 3 onwards. Based on the definition of the current study, it could be concluded that the influenza outbreaks in all 4 old-age-homes were successfully controlled. Figure 1: Flowchart to show the number of residents admitted to hospital before notification to CHP and CILIT and after the intervention from CHP and CILIT and the number who have received oseltamivir prophylaxis and treatment from CHP and CILIT respectively

Comparison of ILI group and non-ILI group (Table 3) There was a total of 28 ILI cases (in which 16 were confirmed influenza A) in the 4 OAHs during the outbreaks. They were compared to those residents who did not develop the illness. The ILI group was found to be of older age (mean age 86.7 years vs mean age 83.6 years, p=0.036), mobility more dependent (immobility: 64.3% vs 43.2%, p=0.035) and more likely to have congestive heart failure (28.6% vs 12.6%, p=0.023). The one-month mortality rate due to pneumonia in the ILI group was significantly higher than the non-ILI group (7.1% vs 0%, p = 0.012). There was otherwise no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the gender, vaccination status, number and other types of comorbid diseases.

Table 3

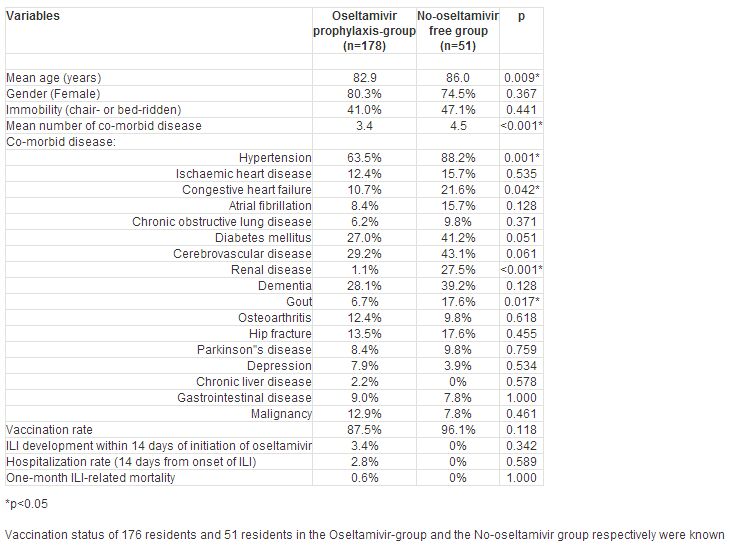

Comparison of residents receiving prophylactic oseltamivir and those who did not (Table 4) There was a total of 229 asymptomatic residents from the 4 OAHs assessed by the CHP and 178 (77.7%) of them were prescribed oseltamivir prophylaxis. The others did not receive this because of a relative contraindication, which was mainly renal impairment. Compared to those who had oseltamivir prophylaxis, residents who did not receive the drug were older (mean age 86.0 years vs mean age 82.9 years, p=0.009) and had more comorbid diseases (4.5 vs 3.4, p<0.001). Both groups did not differ statistically in the gender and mobility level (No-oseltamivir vs oseltamivir group: female 74.5% vs 80.3%, p=0.367; immobility 47.1% vs 41.0%, p=0.441). However, residents who were not given oseltamivir suffered more from hypertension (88.2% vs 63.5%, p=0.001), congestive heart failure (21.6% vs 10.7%, p=0.042), gout (17.6% vs 6.7%, p=0.017) and chronic renal failure (27.5% vs 1.1%, p<0.001). Regarding the health related outcomes of the 2 groups, none (0%) of the No-oseltamivir group developed ILI compared to 6 (3.4%) in the oseltamivir group. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.342). There was also no significant difference in the two-week ILI-related hospitalization rate and the one-month mortality between the two groups (No-oseltamivir vs oseltamivir group: hospitalization rate 0% vs 2.8%, p=0.589; mortality 0% vs 0.6%, p=1.000).

Table 4 : Comparison of residents receiving prophylactic oseltamivir and those without because of a relative contraindication

Discussion The present study demonstrates that the joint effort from the CHP and the CGAT is effective in terminating outbreaks of seasonal influenza in OAHs in Hong Kong. This finding is limited by a lack of a control group to directly compare the attack rates and outbreak duration in the absence of this joint intervention. It is thus possible that implementation of infection control measures including the use of chemoprophylaxis may have coincided with the natural attrition of an epidemic. However, the attack rates from other studies could be up to 43% to 65% and the duration of symptoms up to 23-30 days in influenza outbreaks in which anti-viral prophylaxis was not used.6 Although these are not local data, this gives an estimation of the natural course of the influenza outbreak without intervention. We thus believe that coincidental natural termination in our sample to be unlikely. The overall resident attack rate of ILI during the influenza A outbreak in our study population was 11.2%. This compared favourably with other ILI outbreaks in the western society where the attack rates ranged from 10% to 53%.7-9 During an outbreak, some individuals did not develop the disease while others did. Whether a resident gets the infection would seem to depend on several factors which include (1) the individual factors such as personal hygiene, vaccination status and comorbid disease; (2) the environmental factors such as the ventilation in the OAH, group activities and staff factors and (3) management/ administrative factors such as the competence of infection control officer (ICO) in OAH, the infection control measures to be implemented, the use of chemoprophylaxis. Our study has tried to find out the characteristic features of those residents who contracted the disease during the influenza outbreak. ILI residents, compared to those who did not contract the infection, were older, mobility-dependent and more likely to have congestive heart failure. Another local paper also found that renal disease, apart from older age, to be a risk factor for ILI.3 All this information may be important when one is managing an outbreak in OAH in Hong Kong. In our study, Influenza A (H3N2) virus was found to be the agent causing the outbreaks in all the OAHs. This was compatible with a local finding in 2005 in which 45 of 46 outbreaks (97.8%) were caused by influenza A (H3N2).3 In the US, this virus predominated in 90% of influenza seasons during 1990-1999, compared with 57% of seasons during 1976-1990.10 This virus therefore seems to predominate in the recent decades. In addition, this virus causes a greater number of influenza-associated hospitalization than other influenza virus types or subtypes.11 Our study has shown that the hospitalization rate during the influenza A outbreak in the OAH was 6.0% reducing to 2.5% after the implementation of infection control measures from the CHP and CGAT. Furthermore, influenza A (H3N2) virus is also associated with a higher mortality. Thompson WW et al. reported that among the different respiratory viruses, influenza A (H3N2) viruses were found to be associated with the highest attributable mortality rates, followed by Respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza B and influenza A (H1N1) viruses.10 As in our study, 2 residents died of pneumonia within one month of the infection. The case fatality rate in our sample was 7.1%. This was lower than the rates of 10-20% reported in other literatures.12-15 One of the objectives of an influenza vaccination programme is the prevention of institutional outbreaks.16 Therefore, residents of long-term care facilities is regarded as a target group for vaccination.17 High rates of vaccination can reduce the risk of influenza outbreak in nursing homes.4 Our study, however, showed that despite a wide coverage of influenza vaccination (overall 89.4%) among residents, influenza outbreaks still occurred. Other local and overseas studies also reported similar findings.3,5,8 Bowles SK et al analyzed 11 outbreaks in 10 OAHs in Ontario during 1999-2000 and the percentage of residents vaccinated against influenza ranged from 83% to 97%.5 Vaccine efficacy depends on the degree of similarities between the vaccine strain and the epidemic strain, the age and immunocompetence of the recipient.18 Frail elderly living in OAHs may have a diminished immunologic response to vaccination and hence results in a lower protective efficacy.19 Lower post-vaccination anti-influenza antibody concentrations have been reported among the elderly as compared with younger adults.20,21 A local study on the immune response to influenza vaccination in the community dwelling Chinese elderly showed that influenza vaccination did indeed provoke a protective antibody response.22 This paper did not include OAH residents who are characterized by their frailty and reduced immunity and thus the sero-conversion rate of OAH residents cannot be inferred from that paper. Furthermore, individuals with chronic medical conditions may respond less favourably to the influenza vaccination. These would include subjects with diabetes 23 and those with chronic renal failure on haemodialysis.24 In a study of 50-64 years of age, the vaccine was 60% effective among healthy adults, but only 48% effective among those with high risk medical conditions (which included chronic lung disease, heart disease, diabetes, kidney failure and cancer). This is in line with our study population that over 90% had at least one of the following chronic medical diseases: hypertension, heart disease, lung disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease or dementia. This could be one of the reasons why outbreaks are not precluded in OAHs where most elderly are vaccinated. Having said that, influenza vaccination is still regarded as important in the elderly because it would reduce the risks for ILI-related complications like pneumonia, hospitalization and mortality.25 A local paper has also shown that the mean number of unplanned hospital admissions was significantly lower in the vaccinated group compared to the placebo group.22 Using antiviral medications for treatment and prophylaxis of influenza is a key component of influenza outbreak control in OAHs. Chemoprophylaxis should be administered to all residents, regardless of whether they received influenza vaccinations during the previous fall. When influenza outbreaks occurred in OAHs, our CILIT team visited the OAHs and assessed potential influenza (ILI) cases. Majority of the residents were asymptomatic and they were assessed by CHP and were provided with oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis. However, one-fourth to one-fifth of the residents did not receive the chemoprophylaxis because of a relative contraindication. Our study showed that this frail elderly group who did not receive chemoprophylaxis were older and had more comorbid diseases. More of them were suffering from hypertension, congestive heart failure, gout and chronic renal failure. Yet, they did better than the group given chemoprophylaxis in terms of the ILI infection, hospitalization and mortality. This result is important because it reassures our infection control team that appropriate use of chemoprophylaxis together with the implementation of infection control measures are vital in containing the outbreak, despite the fact that chemoprophylaxis only covers a proportion of the residents (78% in our sample). On the other hand, this also raises a question of whether oseltamivir prophylaxis is effective since the outcome between the two groups did not differ significantly. Nevertheless, the apparent ineffectiveness of pharmacological measure may be due to several factors. First, the time of initiation of the drug and the duration of use. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), when confirmed outbreaks of influenza occur in institutions, chemoprophylaxis with a neuraminidase inhibitor medication should be started as early as possible and it should continue for a minimum of 2 weeks or the drug must be taken each day for the duration of potential exposure to influenza. In our study, the oseltamivir was given at a mean of 5.2 days after the onset of the first case and the drug was prescribed for one week only. Second, the degree of anti-viral resistance was not known in the study population. However, we believe this should not be a major factor because oseltamivir resistance is mainly reported among A (H1N1) viruses. In the United States, approximately 10% of influenza A (H1N1) viruses were resistant to oseltamivir during the 2007-08 influenza season. The European seasonal influenza surveillance reports indicated that about 13% of Influenza A - H1N1 isolates sampled in November & December 2007 showed resistance. In Hong Kong, the Public Health Laboratory Centre detected no oseltamivir resistant influenza viruses in 2006 and 2007 but 5 oseltamivir-resistant influenza (H1N1) viruses out of 62 samples in January 2008 (i.e. 8%). The issue of rapidly developing oseltamivir resistance has to be emphasized as this is likely related to the widespread use for "ILI", when in reality influenza A may not be the commonest cause. A recent local paper found that influenza A only accounted for about 5% of all ILI in residential care homes.26 Although the current study reported outbreaks due to influenza A, these represented ILI episodes during a period when influenza A was prevalent throughout the community. When this is not the case, ILI episodes will be less likely to be due to influenza A. Having said that, the outbreaks in our study involve the influenza A H3N2 virus and oseltamivir resistance of this isolate is not a major problem at present. There are several limitations in our study. Firstly, our study included OAHs in a regional district in Hong Kong and this may limit the generalizability of the finding to other populations. Secondly, the vaccination status of staff in only one OAH was collected. This was important because it has been shown that vaccinating home care staff against influenza can prevent deaths, health service use, and influenza-like illness in residents during periods of moderate influenza activity.27 Thirdly, the diagnosis of a case of ILI depends on the report from the ICO of the OAH, who is not a medical practitioner. Nevertheless, there is a structured reporting system with the specific symptoms of ILI for them to report to minimize the error in diagnosis. Fourthly, among the 28 ILI cases, only 16 cases were confirmed influenza A. 12 of them did not have a definite aetiological diagnosis and they might represent a group of heterogeneous respiratory tract infections due to bacterial infection or viral infection other than influenza A. Lastly, the compliance and adverse effect to the drug treatment was not studied. Future studies may include this in order to have a more comprehensive description of influenza outbreak control in OAHs in Hong Kong. Conclusion Influenza A outbreak does occur even in well-vaccinated OAHs and causes undue hospitalization and mortality. A prompt intervention from the CHP and CGAT is effective in the control of the disease in OAHs of Hong Kong. Whether it is effective to use oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis as an adjunct to non-pharmacological therapy needs further study. Key messages

Ka-chun Chiu, MBBS (HK), MMedSc (HK), FRCP (Glas), FHKAM (Medicine)

Associate Consultant, James K H Luk, MBBS (HK), FRCP (Edin), FRCP (Glas), FHKAM (Medicine) Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital. Leung-wing Chu, MD (HK), FRCP (Edin), FRCP (Glas), FHKAM (Medicine) Consultant in-charge, Hong Kong West Geriatrics Service, TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital. Alice Choi, Registered Nurse, Registered Midwife, Bachelor of Nursing, MBA (Health Services Management) Ward Manager, Department of Nursing, TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr Ka-chun Chiu, 1/F, Associate Consultant Office, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital, 9 Sandy Bay Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|