|

September 2011, Volume 33, No. 3

|

Original Articles

|

How would family physicians facilitate the uptake of HPV vaccination: focus group study on parents and single women in Hong KongAlbert Lee 李大拔, Paul KS Chan 陳基湘, Louisa CH Lau 劉梁彩霞, Tracy TN Chan 陳德雅 HK Pract 2011;33:107-114 Summary

Objective: To gain a better understanding of the general public

in Hong Kong regarding the prevention of cervical cancer and acceptance of HPV vaccination.

Keywords: Cervical Cancer, HPV, Education, Prevention 摘要

目的: 更有效地了解香港公眾對預防子宮頸癌的看法和對接種HPV疫苗的接受程度。

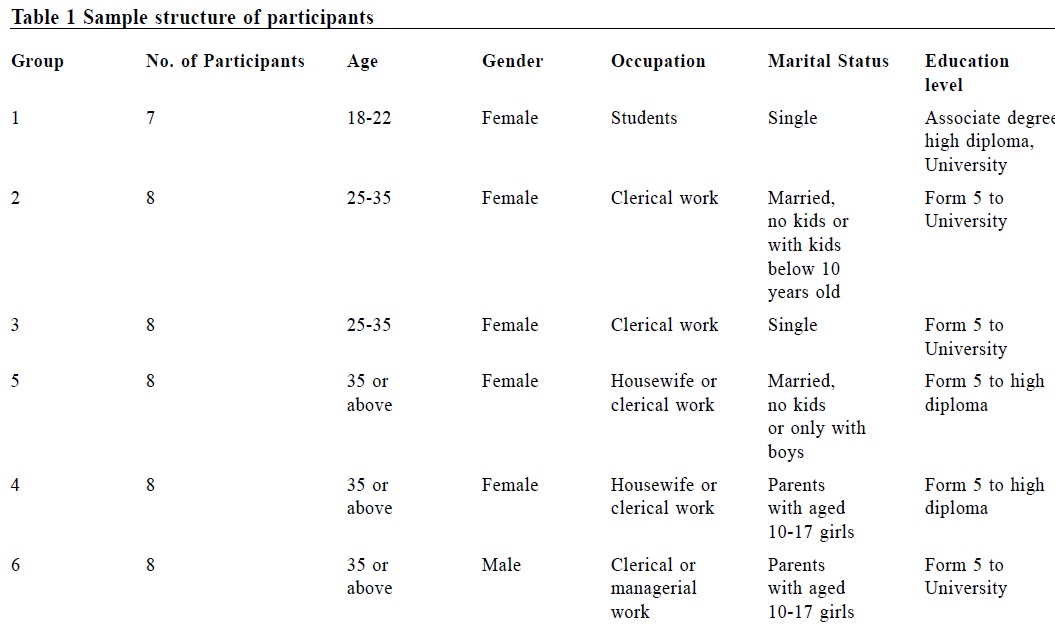

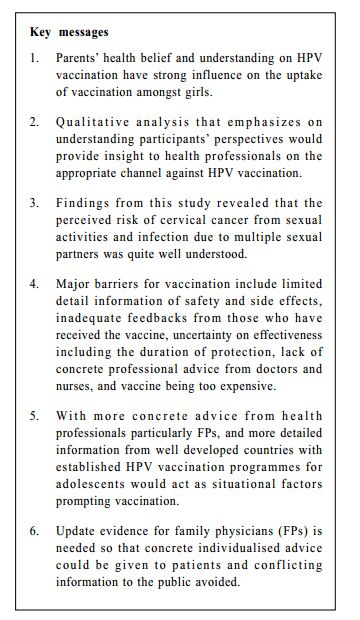

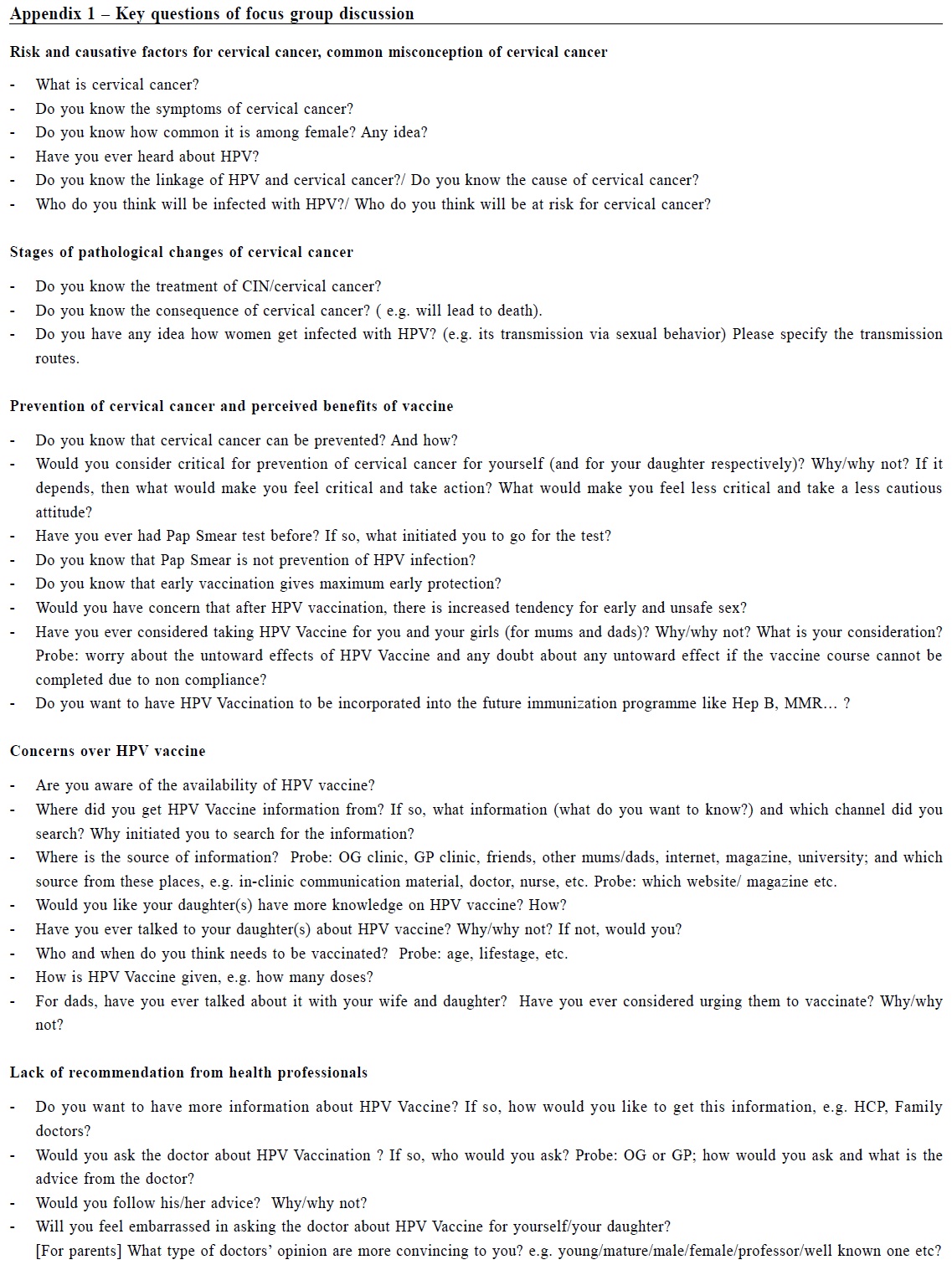

主要詞彙: 子宮頸癌,HPV,教育,預防。 Introduction Cervical cancer is the third commonest cancer in women worldwide 1 and the eighth commonest cause of cancer-related deaths among women in Hong Kong in 2007.2 Virtually all cervical cancers are caused by persistent infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), primarily HPV types 16 and 18.3 In the U.S.A., the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices recommends three doses of HPV vaccine for females who are without previous vaccination, and aged 11-12 years as well as catch-up doses for those 13 to 26 years old.4 However the HPV vaccine initiation among eligible females has remained low with recent estimates of having at least one vaccine dose ranging from 5% to 26%.,5-6 Parents' health-belief and understanding on HPV vaccination have strong influence on the uptake of vaccination amongst girls. Study by Reiter et al has identified that doctors' recommendation, perceived barriers of receiving HPV vaccine and perceived vaccine harms were associated with HPV vaccine uptake.7 It would be useful to explore how those concerns would be addressed in our local context. This study therefore aimed at gaining a better understanding of the behaviour and experience of the general public in Hong Kong regarding the prevention of cervical cancer and acceptance of HPV vaccination, thus providing insight to health professionals on the appropriate channels and touch points to motivate and remove the barriers against HPV vaccination. Methods Six focus groups were conducted in February 2011 amongst parents with and without children and single ladies with no history of HPV vaccination. Five groups of women were recruited according to the age, marital status, and age of their daughters. One group of fathers who had at least one daughter was also recruited to gain a better understanding on the fathers' perspective. The subjects were recruited through a social network via an independent research agency. Participant's demographics data are shown in Table 1. Questions for facilitating focus group discussion on participants' understanding of cervical cancers and HPV vaccination are listed in Appendix 1.

Interviews were video-taped so raw qualitative data would be available for validity check. Data from focus group interviews were transcribed from video-taping. From the interviews, certain words, phrases and ways of thinking were identified and categorized into different headings and themes, and analysed for regularities and patterns. These data were then collated to provide meaningful results. Results Belief and understanding of risk and causative factors for cervical cancer Most participants seemed to be aware of cervical cancer being related to sexual behaviours and numbers of sexual partners. Some were aware of the infectious nature of the disease and heard of HPV being the causative agent.

"…the development of cervical cancer has something to do with sexual intercourse

and other sexually transmitted diseases." CC1 Stages of pathological changes of cervical cancer Young female participants did not seem to have heard of early pathological changes of the cervix that occurs before cancer develops, i.e. cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

"…..causes of CIN should be pressurized life style, menstruationinduced tensing and

relaxing of cervical tissues, inability to fully discharge menstrual blood and tumors.

They reckoned having vaccine injection could prevent CIN from developing." CC1 Misconception of cervical cancer Quite a number of participants including fathers believed that cervical cancer is genetically determined.

"….. it is caused by cellular mutations (DNA) and is related to genetics." CC1 Although most people were aware that breast cancer and cervical cancer were the commonest cancers amongst women, some were still confused between the two. They expressed different concerns towards breast and cervical cancer but their concerns reflected inadequate understanding.

".. removal of the breast would be more noticeable from appearance, which is bigger

problem than the inability to be pregnant." CC1

Prevention of cervical cancer and perceived benefits of vaccine Pap smear was mentioned as a method for preventing cervical cancer. They would practice safe sex after knowing HPV could be contracted through sex. " ..Having Pap smear about once per year or once every two years.." CC4 When discussing vaccination as prevention for cervical cancer, most expressed the necessity for early intervention but for different reasons. Quite a number of females of different age groups with or without daughters expressing best time for vaccination should be before starting sexual activity.

"…the earlier the better. One should consider [vaccination] before their first ever

sexual intercourse." CC1 One participant would take the injection at the age of 35 as they would like to make sure there would not be any side effects by taking the vaccine. "…willing to take the injection before the second peak of the cancer as no plan to have any more children and wanting protection at this age." CC2 Some suggested another critical time around age 50 to 60 when their bodies would not function. However some would not want injection at older age as they become less sexual active. "Due to the weakened immune system, would be more prone to disease like the cervical cancer and therefore would prefer to take the injection around that time to prevent contraction of the disease." CC2 Concerns over HPV vaccine They had concerns about the vaccine's duration of protection. If young children received the vaccination earlier, would the immunity last until their adulthood? They were confused on the issue of the best time to have injection.

"….if the vaccine could only last for 20 years, so what would happen afterwards?"

CC3 As the vaccine is new, people are in general concerned with safety and side effects. They would like to have more information from other countries as well as recommendation from local health authority. The price is also a concern.

"…would have greater confidence in a vaccine if it is being widely used in other

countries, as there would be more data on the reaction to the vaccine on people

with different conditions, and thus could ensure safety." CC1

Lack of recommendation from health professionals Lack of concrete advice and conflicting views from health professionals were identified as another major barrier. Advice from health professionals would facilitate vaccination uptake. Some had received discouraging comments from health professionals.

"I asked a friend of mine who is a nurse, she said that the vaccine is not stable

yet, so I want to wait till it is more stable." CC4 Discussion The Health Belief Model (HBM)8 is one of the most widely used model to understand health behaviours,9 including vaccine uptake.10-11 HBM constructs have been applied to HPV vaccine research,7,11 specifically the perceived risk that cervical cancer is likely to occur, perceived severity and benefits of the vaccine, perceived barriers of vaccination, and factors prompting vaccination (cues to action). Findings from focus groups study would enable deeper understanding of each construct to help us remove the barriers and facilitate actions. Participants from this study appeared to understand that cervical cancer was linked to sexual activities and infection, with increasing risks associated with multiple sexual partners. Only some interviewees were aware of HPV infection and understood pathological changes of cervical cancer, i.e. CIN especially young female. Some had the misconception that cervical cancer was an inherited disease, and were confused about disease nature and severity, as well as the best strategies for prevention. They would consider early vaccination before first sexual intercourse to have better protection and the benefits of vaccination. Fathers were also aware of importance of early protection. The study identified some major barriers for vaccination:

l a relatively new vaccination with limited detail information on safety and side

effects Vaccination uptake rate may increase with more concrete advice from health professionals, particularly from family physicians; and more detail information from well developed countries with established adolescent HPV vaccination programmes, such as the USA. Doctors' recommendation, perceived barriers to vaccination and perceived potential harms of the vaccine strongly correlate with vaccine initiation.7 Results from this study will help us gain a deeper understanding of patients' concerns, which would facilitate FPs in addressing patient issues more specifically and avoid conflicting information. The findings have indicated that most interviewees were at the contemplating stage, according to the staging of change model by Proscaska and Diclementi.12 In order to help them modify their behaviours, FPs should help them consider the 'pros' and 'cons', explore support and barriers, provide further information, and discuss about ambivalence. They need help and support to strengthen self-confidence to initiate vaccination. FPs should use this model to explain how people can change and focus on particular step toward certain behavior change.13 FPs should collate the latest evidence from scientific publications and provide patients with more detailed information to clear up their misconceptions. In this regard, local epidemiological information, including the peak ages of infection and the proportion of cervical cancers and pre-cancers expected to be covered by the current vaccines, would be more relevant.14-17 FPs with thorough understanding of patients' background from both medical and social perspectives would provide specific advice to individual case rather than general advice. Hong Kong's adolescent girls are receptive towards HPV vaccination. However, barriers still exist including cost, uncertainty on the duration of vaccine effectiveness, a low perceived risk of HPV infection, no immediate perceived need for vaccination, and anticipated family disapproval. Conducive factors for vaccination were perceived family and peer support and medical reassurance on safety and efficacy of vaccine.19 Through resolving patients' misconceptions and perceived barriers, FPs can enable them to become more involved in the planning process hence increasing their motivation for change.18 FPs can also facilitate vaccination uptake through providing health seminars, online health education and support to local campaigns for prevention of cervical cancer. Social norm is also an important variable forming an intention to change according to theory of reasoned action.20 FPs' deeper involvement at both personal and community level would help and build a more positive social norm for cervical cancer prevention. Findings from focus group of fathers revealed that fathers wanted more scientific information before making decision. Cancer develops after many years of persistent infection.21 Young females' unawareness on cervical cancer's pathological stages may affect their compliance to periodic screening. Primary prevention by minimizing exposure might have limited efficacy because condoms is less optimal for preventing HPV infection compared to other sexually transmitted diseases. In addition, high frequency of HPV exposure among sexually experienced individuals and high transmissibility of HPV infection make primary prevention by minimizing exposure unrealistic.22 The cumulative lifetime risk of infection is likely to be greater than 75% for one or more genital HPV infection.22 In a recent Hong Kong study, young age and smoking were found to be the most consistent independent risk factors observed across different HPV groups,23 Young females seemed to have less clear understanding of cervical cancer but they were found to be very receptive for vaccination as protection. Smoking rates amongst young women were found to be high in various districts in Hong Kong.24-25 Vaccination as primary prevention would be an option for protection especially among younger age groups before engaging in sexual activities. A theoretical Finnish model predicted that once the full impact of vaccination is reached, the annual proportion of cases of HPV16- associated cervical cancer prevented would reduce with increasing recipients' age.26 Girls in Finland under 18 are considered to have lower sexual activities compared to those in the USA. Therefore, vaccination could be effective in protecting Hong Kong young female from contacting HPV even in population with low level of sexual activities.26 The qualitative nature of this study limits the the generalizability of our results. Nevertheless, a qualitative approach has enabled us to gain a deeper understanding on how to make changes. This study might not cover all age groups of women in different categories of work. More study on male attitudes towards vaccination should also be considered sometime in the near future.

Conclusion The study reveals that women in Hong Kong have incomplete knowledge about cervical cancer and vaccination. Information from countries with well developed adolescent vaccination programmes should be given to potential recipients. Update evidence for FPs is needed so that concrete personalized advice can be given to patients, thus avoid conflicting information to the public. FPs should engage in community health promotion programmes for preventing cervical cancer, facilitating a 'social norm' to consider vaccination as primary prevention. Acknowledgement The authors would like to thank GlaxoSmithKline for the Education Sponsorship in supporting this study.

Albert Lee, MD (CUHK), FHKAM (Fam Med), FFPH (UK)

Director Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Professor, School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Paul KS Chan, MD (CUHK), FRCPath (UK), FHKAM (Pathology) Professor Department of Microbiology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Louisa CH Lau,, DipNurAdm (CUHK), Dip Biostat (CUHK), HV, SRN Project Coordinator Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Tracy TN Chan, BSocSc (OUHK), MA (HKPolyU) Research Assistant Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Professor Albert Lee, Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 4th Floor, Lek Yuen Health Centre, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong SAR. Email: alee@cuhk.edu.hk

References

|

|