March 2012, Volume 34, No. 1 |

Original Articles

|

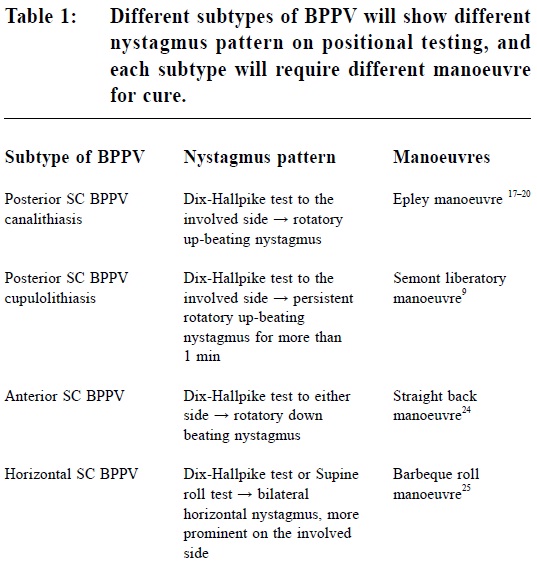

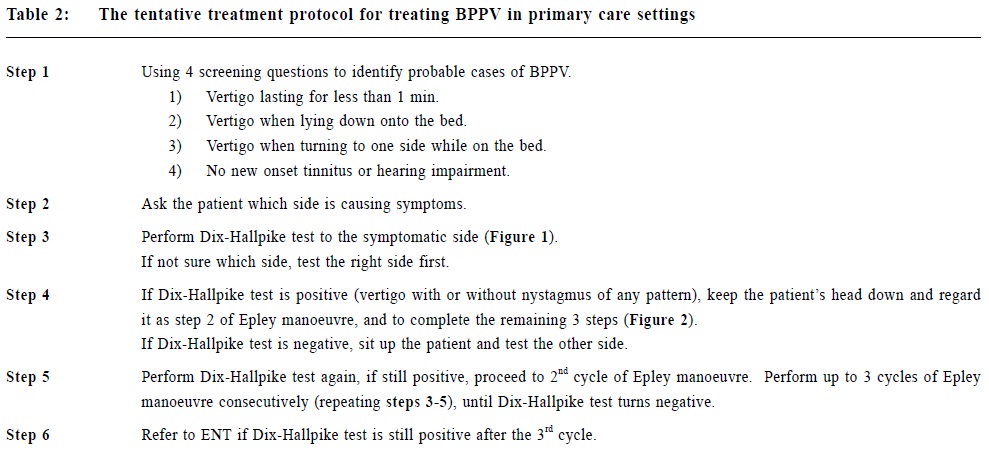

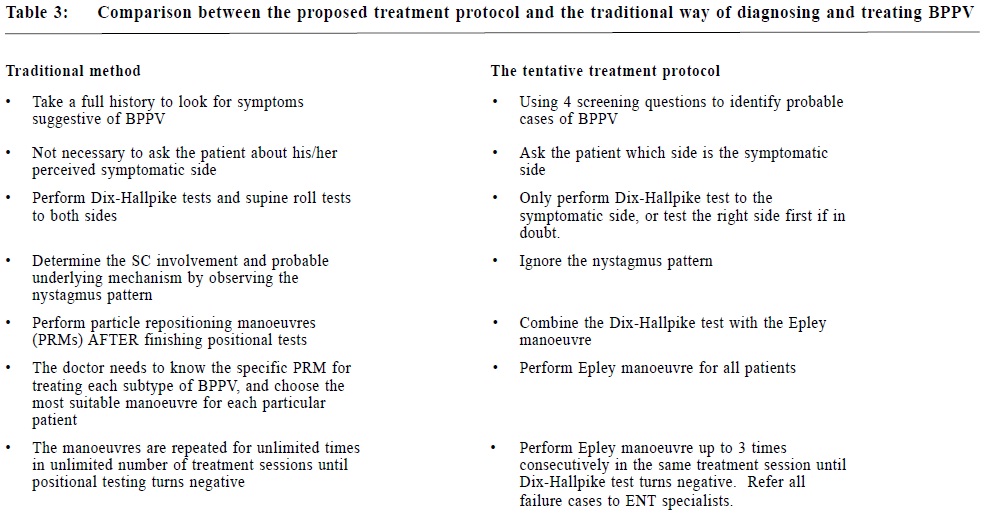

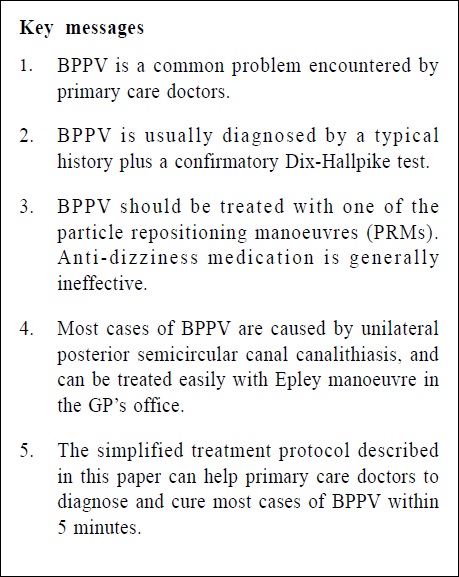

New approach for treating benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in primary care settings – a pilot studyTing-bong Chan 陳定邦, Kenny Kung 龔敬樂, Augustine Lam 林璨 HK Pract 2012;34:6-16 Summary Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a tentative treatment protocol designed for treating benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in primary care settings. Design: Single arm prospective trial. Subjects: The new treatment protocol involves the use of 4 questions to screen for probable cases of BPPV, performs Dix-Hallpike test only to the symptomatic side and incorporates it into the Epley manoeuvre, disregards the nystagmus pattern, performs up to 3 cycles of Epley manoeuvre in one treatment session, and refers all failure cases to ENT specialists. All doctors in a General Outpatient Clinic (GOPC) were invited to identify probable cases of BPPV with the 4 screening questions, and refer to the main author for management. Phone follow-up was performed at 1 week and 4 weeks after treatment. Main outcome measures: Patients’ self report of disappearance of positional vertigo at 1 day, 1 week and 4 weeks after treatment. Results: 14 patients with “objective” BPPV and 4 patients with “subjective” BPPV (no nystagmus on positional testing) were identified. In the objective BPPV group, 11 patients completely recovered and 1 patient partially improved in the first week after treatment, giving an overall success rate of 85.7%. There were too few patients in the subjective BPPV group for analysis. Conclusion: The new treatment protocol appears to be highly effective for treating patients with objective BPPV although this is only a small pilot study. Further trial with larger number of patients is required. Keywords: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), protocol, screening questions, Epley manoeuvre, primary care 摘要 目的:評估以新方案在基層醫療為良性陣發性位置性眩暈(BPPV,又稱耳石移位)進行試驗性治療的成效。 設計:單臂前瞻性研究。 對象:治療方案為:以4條問題篩選有可能為BPPV的病例。衹對有症狀的一側進行Dix-Hallpike測試,並將其融入Epley Manoeuvre。無論眼震模式如何,在同一治療過程中最多進行3次Epley Manoeuvre操作。將無效病例轉介給耳鼻喉專科醫生。在單一綜合門診診所內的醫生均被邀請採用上述4條篩選問題來識別有可能為BPPV的病例,並轉介給作者作治療。在治療後1週及4週進行電話隨訪。 主要測量內容:於治療後1天、1週及4週,病人自我報告位置性眩暈病徵的消失。 結果:共發現1 4例“客觀”BP PV及4例“主觀”BP PV(無眼球震顫)。在治療後一週,客觀 BPPV病例中有11例痊癒,1例得到部分改善,整體成功率為85.7%。因主觀 BPPV的案例過少,未能進行分析。 結論:雖然這只是一項小規模試點研究,但新方案似乎對治療客觀BPPV非常有效。有必要對更多患者作進一步研究。 主要詞彙:良性陣發性位置性眩暈(BPPV),治療方法,篩選問題,Epley manoeuvre,基層醫療 Introduction Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a common problem encountered in primary health care. It is one of the commonest causes of vertigo,1,2 with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%.3 BPPV is characterized by repeated episodes of vertigo lasting for less than 1 minute, triggered by various head movements. The duration of BPPV symptoms ranges from several days to several months;4 spontaneous recovery is common, but recurrence also occurs frequently. BPPV is usually diagnosed by a typical history and confirmed by positional testing. BPPV generally does not respond to medical treatment, and should be treated with one of the particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRMs). BPPV is not really a “benign” disease. The vertigo episodes are very unpleasant for patients. Elderly patients suffering from BPPV were found to have lower activities of daily living (ADL) scores, with increased risk of falls and are more likely to have depression.5 It is believed that most patients with BPPV are suffering from “canalithiasis”,6,7 where free floating particles called canaliths or otoliths are present in one of the three semicircular canals (SC). After having canalithiasis for prolonged period of time, some otoliths may become attached to the cupula, leading to “cupulolithiasis”8 which require more vigorous manoeuvres for cure.9 80-90% cases of BPPV are due to posterior SC problem (P-BPPV).10-12 Horizontal SC involvement (H-BPPV) is relatively rare, accounting for 5-10% of BPPV cases.13,14 Anterior SC involvement (A-BPPV) is very rare , mainly occurring as a complication secondary to various particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRMs).15 More than 90% of BPPV occurs unilaterally.16 “Objective” BPPV vs “Subjective” BPPV The diagnosis of BPPV is usually confirmed by a positive Dix-Hallpike test, defined as the presence of BOTH vertigo and nystagmus on testing, which usually occur after a brief latency of several seconds, and usually last for 10-30 seconds. However, it is also well known that some patients with “subjective BPPV” can have vertigo without observable nystagmus on testing and may still respond to various particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRMs).17,18 Unfortunately, without nystagmus one can never confirm the diagnosis of BPPV unless the symptoms respond readily to the curative manoeuvres. Without nystagmus one can never determine the SC involvement and hence cannot choose the most suitable manoeuvre for each particular patient. Therefore, patients with subjective BPPV are usually excluded from major BPPV treatment trials. Management of BPPV in primary health care setting: the current situation Patients suffering from BPPV usually consult a general practitioner (GP) initially. However, the diagnosis is usually missed, ineffective medical treatment and unnecessary investigations are usually offered, resulting in prolonged suffering and unnecessary medical expenditure.19-21 In the United States, it costs approximately US$2000 to arrive at the diagnosis of BPPV; the health care cost associated with the diagnosis of BPPV alone approaches US$2 billion per year.22 A recent survey on a group of 42 doctors working in Hong Kong’s General Outpatient Clinics (GOPCs)23 revealed that only 4.8% actually performed curative manoeuvres for BPPV patients. Common reasons for not knowing or performing these manoeuvres included insufficient consultation time (54.8%), lack of training (38.1%), and the misconception that Epley manoeuvre is difficult to perform (11.9%). Treatment provided to BPPV patients were medication (28.6%), lifestyle modification advice (11.9%) or both (52.4%). GOPC doctors were also found to have a lot of misconception on the symptomatology of BPPV, resulting in difficulties in making the correct diagnosis. Even if the diagnosis of BPPV is made, the waiting time for a referral to a public ENT specialist clinic in Hong Kong is usually in terms of months. There is therefore an urgent need to improve the management of BPPV in primary care settings. Why is a new treatment protocol for treating BPPV needed in the primary care setting? The treatment for BPPV patients is not straight forward. One needs to determine the SC involvement and probable underlying mechanism by performing a Dix-Hallpike test and supine roll test to both sides and observe the nystagmus pattern (Table 1). To treat all BPPV subtypes properly, one needs to learn at least 4 different curative manoeuvres. Such information and techniques could be too complicated for primary care doctors who have no prior experience in treating BPPV. Furthermore, as briefly mentioned, primary care doctors may not be able to perform detailed manoeuvres because of consultation time constraints. Therefore, in order to encourage more primary care doctors to start treating BPPV patients, a new treatment protocol which is simple, easy to learn and not time consuming should be developed. Developing a simple screening questionnaire to identify BPPV cases in primary care setting can be helpful. Rationale behind the proposed new treatment protocol BPPV treatment can actually be simplified substantially based on the following facts and arguments:

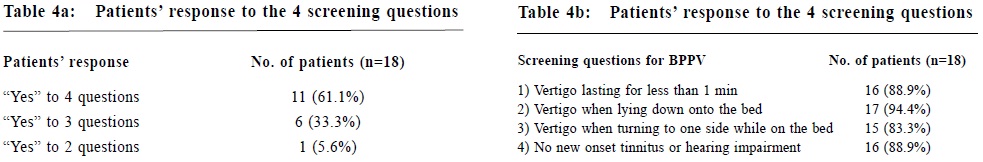

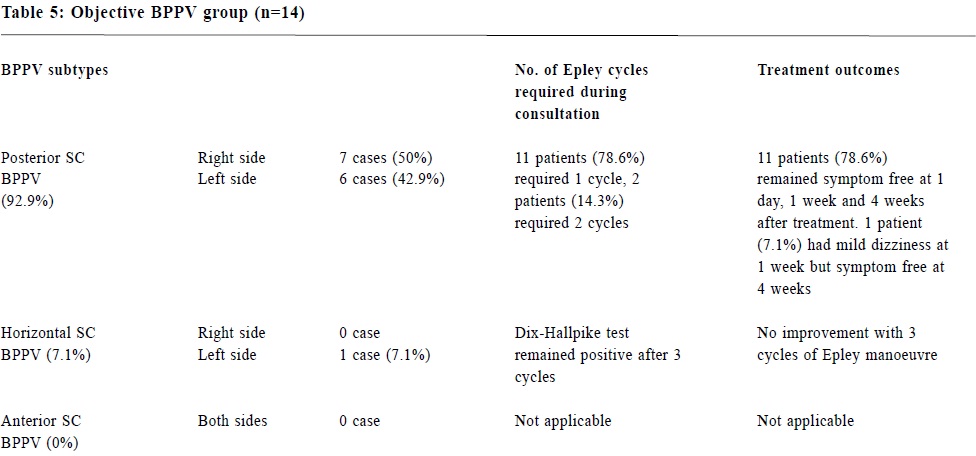

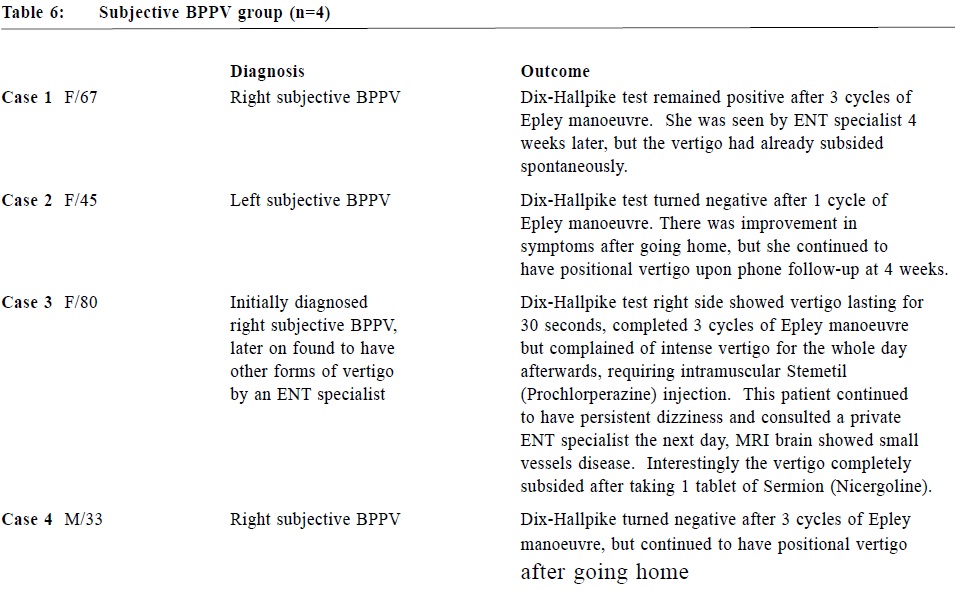

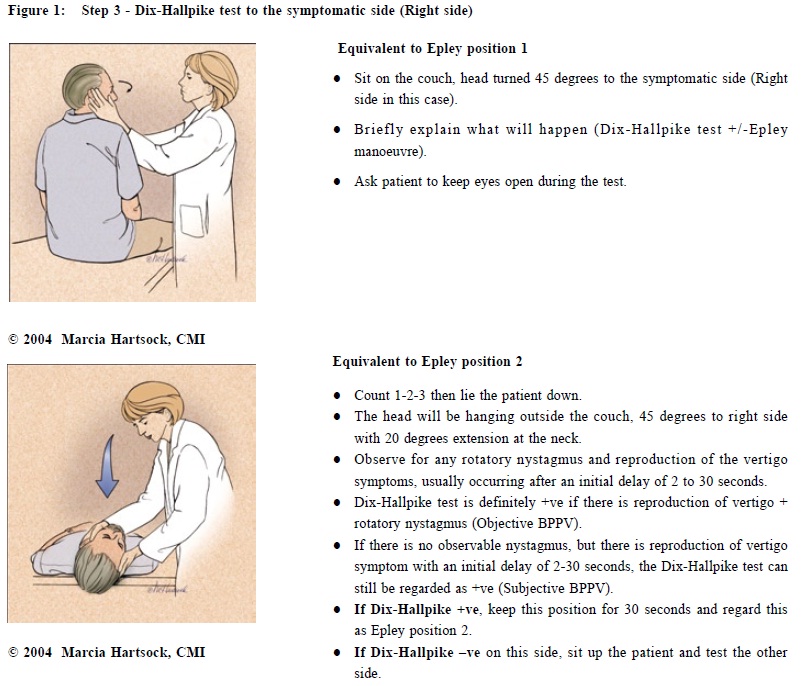

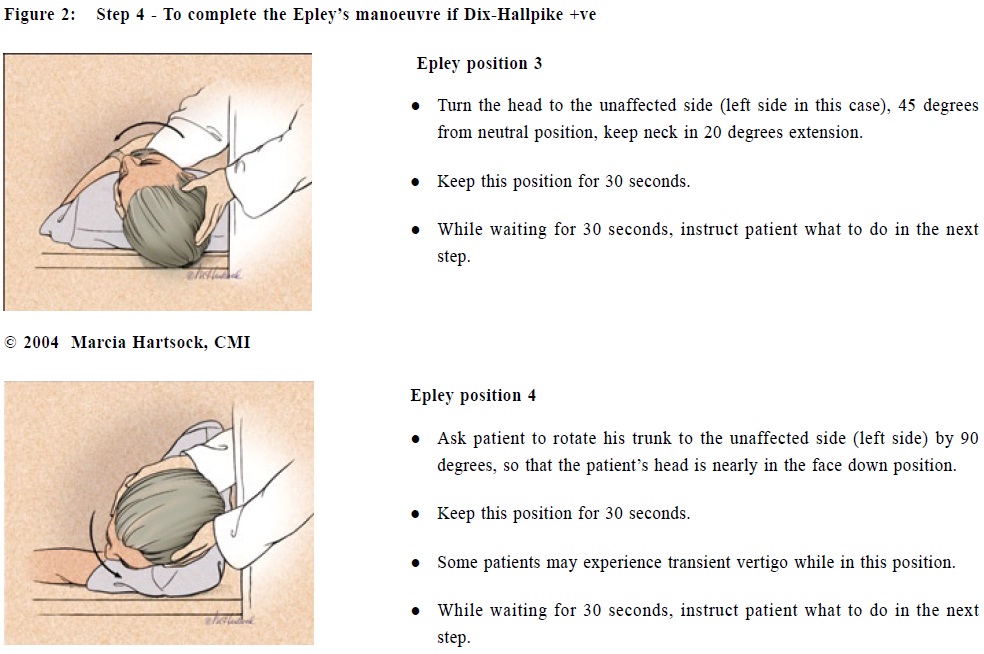

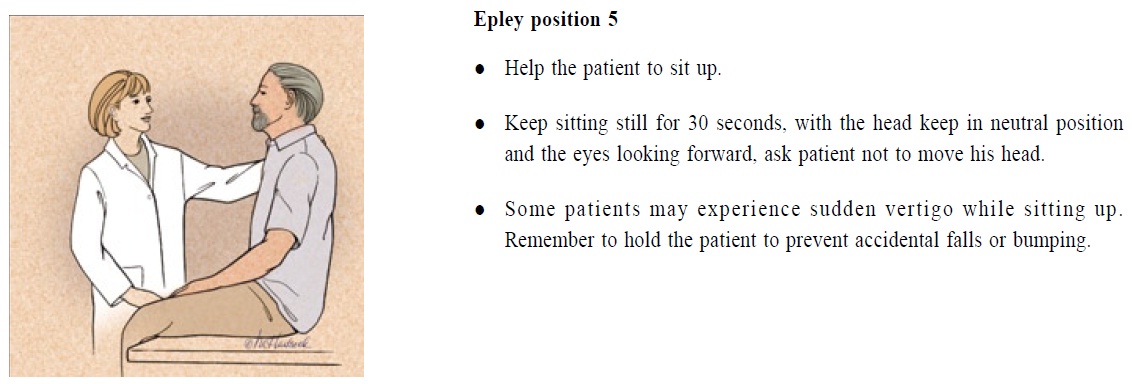

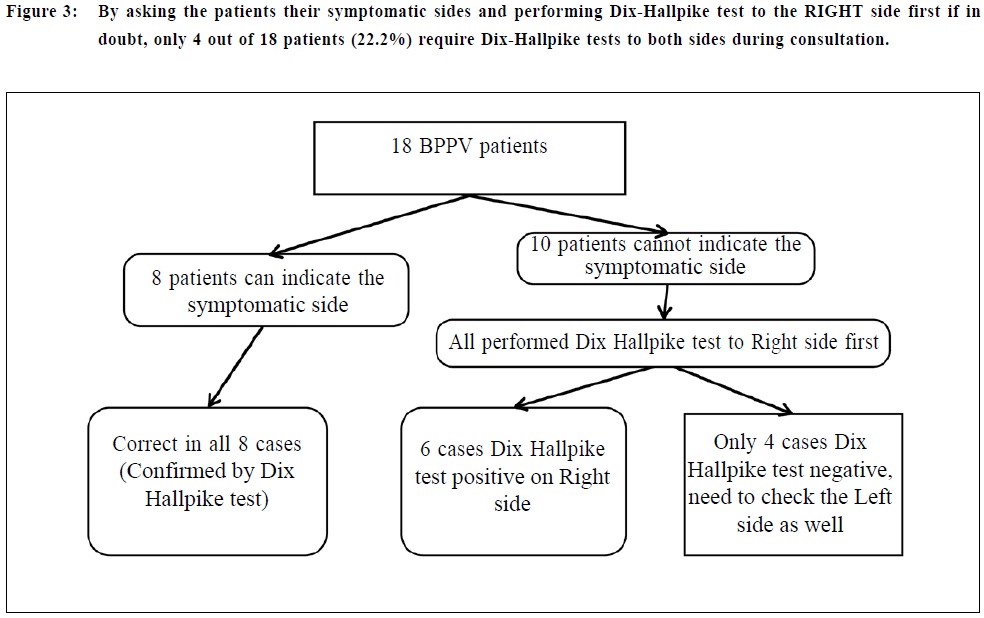

The 4 screening questions 4 simple screening questions were designed to help identify probable cases of BPPV in a brief consultation session. BPPV patients typically experience transient vertigo when getting up in the morning, when lying down onto the bed, and when turning onto their side.17 The “morning dizziness” of BPPV may be easily confused with the dizziness due to postural hypotension or anaemia. On the contrary, transient vertigo occurring when lying down onto the bed or when turning to one side while on the bed is quite unique for BPPV. Although patients suffering from other causes of vertigo may also experience increase in dizziness when changing posture, such dizziness almost always lasts longer than 1 minute. BPPV does not cause tinnitus or hearing impairment, but patients suffering from other forms of peripheral vertigo may have these symptoms. Therefore, people are most likely suffering from BPPV if they experience vertigo episodes which 1) last for less than one minute, 2) occur when lying down onto the bed or 3) when turning to one side while on the bed, and 4) when there is no new onset of tinnitus or hearing loss. Not every BPPV patient will meet all 4 screening criteria, for example, some patients with cupulolithiasis may have vertigo lasting for 1-2 minutes, and BPPV may coexist with other diseases affecting hearing. These questions are only for screening purpose and all suspected cases should be confirmed by positional testing. Methods The tentative treatment protocol for treating BPPV in primary care setting is shown in Table 2 and 3. All doctors in a GOPC participated to identify probable cases of BPPV with the 4 screening questions. All cases presenting with vertigo meeting at least 2 criteria out of 4 were seen by a trained family physician on the same day. Patients with contraindications for Dix-Hallpike test or Epley manoeuvre, namely recent retinal detachment, unstable medical condition, unstable cervical spine, severe carotid or vertebral artery stenosis and orthopaedic conditions hindering movements required for the manoeuvres were excluded from the study. Dix-Hallpike tests were performed according to the new treatment protocol. All cases with positive Dix-Hallpike test (genuine vertigo with or without nystagmus) were included in this study, and were treated according to the new treatment protocol. Patients with symptoms highly suggestive of BPPV but Dix-Hallpike tests negative for both sides were thought to have probable BPPV which may have spontaneously subsided shortly before the consultation, and were excluded from the study. Telephone follow-ups were performed at 1 week after treatment to ask for any change in vertigo symptoms from day 1 to day 7 after treatment. Further phone follow-ups at 4 weeks after treatment were performed for those cases who reported improvement at 1 week. The primary outcome of this study is patients’ self-report of disappearance of positional vertigo at 1 day, 1 week and 4 weeks after treatment. Patients with persistent positional vertigo at 1 week or 4 weeks were regarded as treatment failure. The subjects were divided into 2 groups for analysis: patients with observable nystagmus during Dix-Hallpike tests were assigned to the “Objective BPPV group” and those with vertigo only during testing were assigned to the “Subjective BPPV group”. Results Between January and April 2010, 31 patients with symptoms suggestive of BPPV were encountered by the main author or referred by other doctors to the main author for further management. 18 patients were found to have either objective or subjective BPPV and were recruited in this pilot study. They were 8 males (44.4%) and 10 females (55.6%) aged 33-83, (average age 61.7). The average duration of BPPV symptoms before receiving treatment was 13 days (ranged from 3 to 42 days). Seven patients (38.9%) had a past history of BPPV, with four patients within the previous year. Only one had ever received particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRMs) in the past. 13 patients were excluded from the study: 9 patients were found to have other causes of dizziness such as vestibular neuronitis, and 4 patients were suspected to have BPPV on history taking, 3 of whom were found Dix-Hallpike test negative bilaterally, and were thought to have probable BPPV which had spontaneously subsided shortly before the consultation and 1 patient was thought to have BPPV but the manoeuvres were contraindicated in view of his spine problem. Responses to the 4 screening questions 11 patients (61.1%) answered yes to all 4 questions, while 6 patients (33.3%) answered yes to 3 questions (Table 4a). 16 patients (88.9%) experienced vertigo of less than 1 minute during BPPV attacks, 17 (94.4%) had vertigo when lying down onto the bed, 15 (83.3%) had vertigo when turning to their side, 16 patients (88.9%) did not notice any co-incidental new onset tinnitus or hearing loss (Table 4b). Determine the symptomatic side 8 patients (44.4%) were able to indicate the symptomatic side, and interestingly all of them were correct according to Dix-Hallpike test results. For the other 10 patients, Dix-Hallpike test was performed to right side first, and 6 of them (60%) were found to have right sided BPPV. In other words, only 4 patients out of 18 (22.2%) required Dix-Hallpike test to both sides during the consultation (Figure 3). The objective BPPV group 14 patients (77.7%) were found to have objective BPPV as evidenced by observable nystagmus during Dix-Hallpike test (Table 5). 7 cases (50%) of right P-BPPV, 6 cases (42.9%) of left P-BPPV and 1 case (7.1%) of left H-BPPV were identified. 11 cases (78.6%) became Dix-Hallpike negative after 1 cycle of Epley manoeuvre and 2 cases (14.3%) required 2 cycles. Only one case (the H-BPPV case) remained Dix-Hallpike test positive after 3 cycles of Epley manoeuvre and was concluded as a failure. This patient was treated with Barbecue roll manoeuvre afterwards, complicated by incipient left posterior SC BPPV and subsided again after further Epley manoeuvre. Apart from this case, no other complication was observed in the objective BPPV group. Telephone follow-up was performed for the 13 cases with negative Dix-Hallpike tests after treatment. At 1 week, 11 patients reported resolution of positional vertigo from day 1 after treatment, and remained symptom free at 4 weeks; 1 patient continued to have significant BPPV symptoms at 1 week, and was regarded as treatment failure. Another patient reported mild residual dizziness at 1 week, which was gradually improving and became symptom free at 4 weeks. The overall success rate was 85.7% (12 out of 14). The subjective BPPV group Only 4 patients were regarded as having subjective BPPV. One patient was later on confirmed as not having BPPV. One patient spontaneously recovered 1 month after initial treatment failure, and the other two showed poor response to treatment (Table 6). Discussions This simplified treatment protocol showed promising results for objective BPPV. In this small series of 14 cases of objective BPPV, more than 90% subjects were suffering from P-BPPV which can be treated by Epley manoeuvre. 11 cases (78.6%) required 1 cycle of combined Dix-Hallpike-Epley manoeuvre, and 2 cases (14.3%) required 2 cycles. As each cycle only takes 2 minutes, more than 90% of cases required less than 5 minutes to complete the manoeuvres, which is quite affordable for a busy primary care doctor. 2 cases continued to have BPPV symptoms of different intensity after going home, despite Dix-Hallpike test turning negative during the treatment session. These patients may have residual otoliths in the posterior SC, bilateral BPPV or multi-canal involvement, and they may benefit from bilateral positional testing and more specific manoeuvres. The authors intentionally omitted the need to differentiate the pattern of nystagmus in this treatment protocol, which is designed for primary care doctors who are inexperienced in diagnosing and treating BPPV. Recognition of these nystagmus patterns needs experience; even if an inexperienced doctor is able to recognize the characteristic nystagmus of H-BPPV or A-BPPV, he/she may not know how to perform the specific manoeuvres and the patients would still require ENT referral. The aim of this simplified treatment protocol is to encourage primary care doctors to start recognizing and treating BPPV patients in their daily practice. After gaining experience in treating some P-BPPV cases, doctors may become motivated to learn more about the specific treatment for various subtypes of BPPV. Most patients in this pilot study tolerated theDix-Hallpike tests and Epley manoeuvres very well, although one patient with suspected subjective BPPV experienced increase in dizziness after 3 cycles of Epley manoeuvres, and one patient with left H-BPPV was converted to left P-BPPV after Barbecue roll manoeuvre. Although these manoeuvres are very safe in general, special care is required for patients with neck disease or unstable medical conditions.33 Some patients may experience severe nausea and even vomiting during the treatment. For patients with stiff neck or unstable cervical spine, a tilt table and a modified manoeuvre involving trunk movements instead of neck movements may be required. Rarely BPPV can convert from one SC to another SC during treatment, leading to persistent symptoms requiring further curative manoeuvres.15 This pilot study showed very disappointing results for the subjective BPPV group. Although subjective BPPV is a well known entity, only very few research papers addressed its treatment. Tirelli G et al reported a 6 0% complete recovery rate in patients with subjective BPPV after performing a “Modified Particle Repositioning Procedure”,22 but this manoeuvre involves 7 positions and takes 18-23 minutes to complete the whole process. Haynes D et al showed an 86% improvement rate after performing Semont liberatory manoeuvre to 35 cases of subjective BPPV.18 This manoeuvre is well known and is easy to perform, but the procedure is more vigorous compared to Epley manoeuvre, and may not be suitable for frail elderly or people suffering from neck problems. Further studies are required to determine whether Epley manoeuvre or Semont manoeuvre is more efficacious and convenient for treating subjective BPPV in primary care settings. In the current medical literature, virtually all studies on BPPV were being performed by ENT tertiary referral centres or other specialist settings, and there is lack of data on BPPV management in the primary care sector. As most people suffering from BPPV will consult a primary care doctor initially, and most cases will respond to simple manoeuvres as described in this study, the authors strongly believe that BPPV should be regarded as a primary care problem and extensive studies should be performed to improve its treatment by primary care doctors. Conclusion The current pilot study on a simplified treatment protocol for treating BPPV in primary care settings showed promising results for objective BPPV cases. The number of subjective BPPV cases was too small for analysis. Further study on this treatment protocol with larger number of patients, preferably from multi-centre, is necessary. Acknowledgements I would like to thank colleagues in the Ma On Shan Family Medicine Centre, especially Dr Cheung Yu, Dr Cheung Yuen Yee Cherrie, Dr Cheung Tat Cheong, Dr Chow Kam Fai, Dr Leung Wing Kit, Dr So Fong Tat, Dr Lam Lee Wah, for their participation in this study.

TB Chan, MBBS (HK), Dip Med (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP Resident Kenny Kung, MRCGP, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Associate Consultant in Family Medicine, Augustine Lam, FHKCFP , FRACGP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Correspondence to: Dr TB Chan, Ma On Shan Family Medicine Centre, G/F, 609 Sai Sha Road, Ma On Shan, N.T., Hong Kong SAR. References

|

|