|

December 2014, Volume 36, No. 4

|

Update Article

|

Use of ambulatory electrocardiography (AECG or Holter) for patients with symptoms related to cardiac arrhythmia in the primary care setting: a case series reviewLap-kin Chiang 蔣立建,Lorna Ng 吳蓮蓮 HK Pract 2014;36:133-139 Summary This case series involved 318 consecutive Holter monitoring performed in a regional primary care clinic of Hong Kong during the period 2010 to 2013. The most frequent presenting symptom was palpitation, which accounted for 76.7% of cases. 139 cases (43.7%) of Holter monitoring showed significant cardiac arrhythmia. Long QT syndrome (10.7%) was the commonest condition detected. Patients older than 80 years, or with concomitant hypertension or ischaemic heart disease were more likely to have significant cardiac arrhythmia (P < 0.05). 摘要 此案例系列研究分析了318例從2010年至2013年在香港某間基層醫療診所完成了動態心電圖監測的案例。最常見的表現症狀是‘心悸’, 佔所有案例的76.7%。139例(43.7%)動態心電圖監測有重要的心律失常。最主要的發現是長QT綜合症(10.7%)。如患者是年紀超過80歲,或者同時患有高血壓或缺血性心臟病更可能有重要性心律失常(P值 <0.05)。 Introduction Ambulatory electrocardiography (AECG or Holter) is a portable recorder that registers the ECG continuously during a prolonged period, usually for 24 hours. It allows diagnosis of transient disturbances of cardiac rhythm and conduction. According to the recommendations from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)1, Holter can be used to assess symptoms suggestive of underlying cardiac rhythm disturbance, including unexplained recurrent palpitations, unexplained syncope, near syncope, or episodic dizziness where the cause is not obvious. The Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department (FM & GOPD) of Kwong Wah Hospital has direct access to Holter monitoring. This case series report will review the patient characteristics, clinical features and outcomes of all Holter monitoring ordered by FM & GOPD doctors in the primary care setting. Objectives

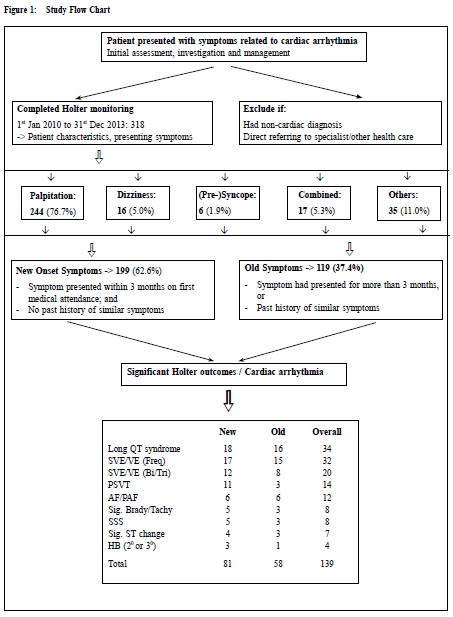

Methodology Study population Consecutive patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of cardiac arrhythmia and had Holter monitoring performed during the period 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2013 in the Kwong Wah Hospital FM & GOPD were studied. (Figure 1). Clinical details including demographics, presenting symptoms and Holter results were collected. Presenting symptoms were stratified into five categories: palpitation, dizziness, syncope/presyncope/loss of consciousness, combined symptoms and “others” (including chest pain, incidental abnormal electocardiography (ECG) finding etc). Presenting symptoms were further divided into ‘new onset’ (symptoms that occurred within three months before clinic visit) or ‘old’ symptoms (symptoms present for more than three months). Patients with confirmed non-cardiac causes of their symptoms or requiring urgent referral for specialist care were excluded. Holter Monitoring and Definition All Holter monitoring performed by the Cardiac Unit at Kwong Wah Hospital used a standard device (Philips Zymed Digitrak Plus). Standardised reports verified by authorised Cardiac unit doctors are generated and sent to the referring physicians. Content of the reports included patient demographic data, heart rate data and variability, QT analysis, ST episode analysis, pacer analysis, ventricular ectopy, supraventricular ectopy and atrial fibrillation. The Holter outcome classification in our study was dichotomous (significant cardiac arrhythmia versus insignificant cardiac arrhythmia or normal) to reflect the reality of general practice decision making.2 All diagnosis of significant cardiac arrhythmia will be referred to medical specialist for further evaluation and management. The following definitions for various Holter abnormalities were used: - Frequent ectopy: > 15/1,000 atrial or ventricular ectopic beats.3 - Significant pause: RR interval of ≧ 2.8 seconds.3 - Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF): an irregular rhythm without P-wave activity sustained for ≧ 10 beats.3 - Long QT syndrome: corrected QT interval (QTc) ≧ 440 ms.4 - Bigeminy: pairs of normal and premature complex.5 - Trigeminy: a premature complex that follows two normal beats.5

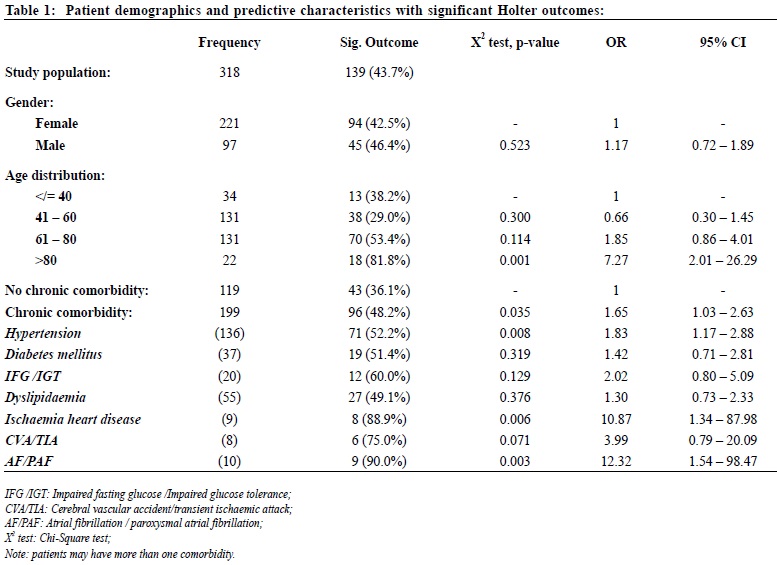

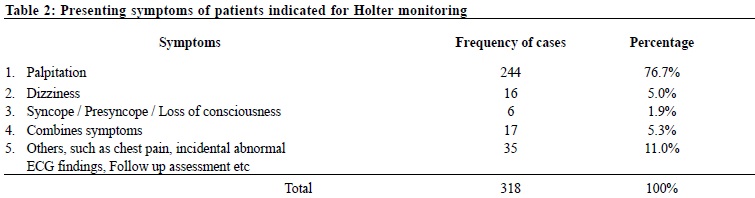

The following were considered to be significant Holter findings: 2,6 -ventricular tachycardia (VT), -paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), -atrial fibrillation (AF, including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, PAF), -atrial flutter, -atrial tachycardia, -supraventricular or ventricular ectopy (SVE or VE) occurring in couplets or having a multifocal origin, -high grade atrioventricular (AV) block, i.e. second degree or third degree, -sick sinus syndrome (SSS), -long QT syndrome, -or significant change in ST segment. Insignificant cardiac arrhythmia encompassed patients with non-pathological atrial or ventricular ectopy, e.g. sporadic, occasional unifocal ectopy.2 Statistical analysis Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentages will be used to summarise the baseline characteristics and outcome measures. Chi-square test and multivariate analysis with regression were used to assess the predictive patient characteristics associated with significant cardiac arrhythmia. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS Inc., United States). Results In the period from 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2013, 318 Holter monitoring were performed for 97 male and 221 female patients. Their mean (SD) age were 62.8 (16.7) and 58.3 (14.3) years old respectively. The demographic characteristics of patients are summarised in Table 1. 62.6% patients had at least one chronic comorbidity. Patients’ presenting symptoms are summarised in Table 2. The majority of patients 244 (76.7%) presented with palpitations. 199 (62.6%) patients presented with new onset symptoms.

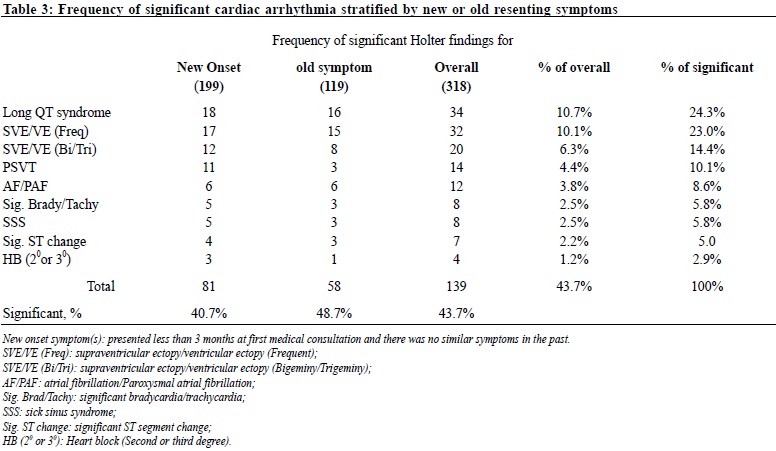

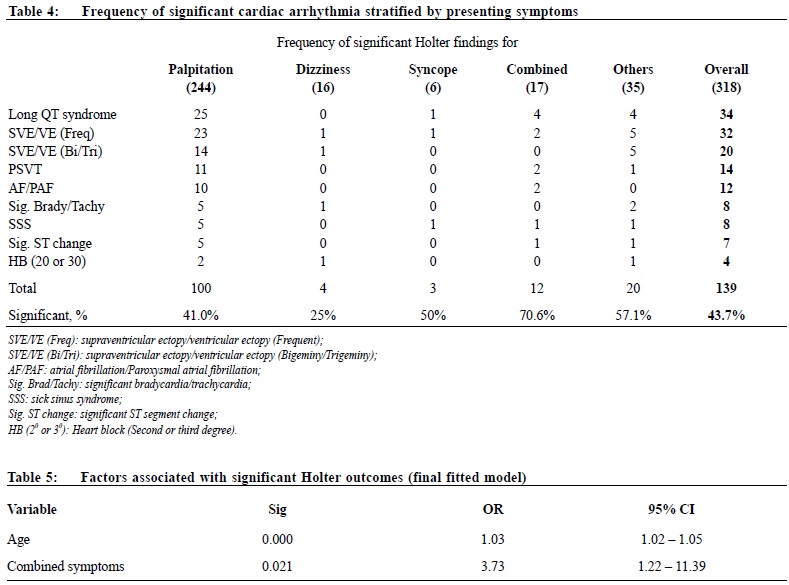

139 patients (43.7%) were detected by Holter to have significant cardiac arrhythmia and all of them were referred to our Department of Medicine for further management. 81 (40.7%) and 58 (48.8%) patients with new and old onset symptoms respectively had significant cardiac arrhythmia (Table 3). Among patients with significant cardiac arrhythmias, the majority presented with combined symptoms (70.6%), and a large proportion presented with palpitation (41.0%), or syncope/presyncope/loss of consciousness (50%). (Table 4) The Holter monitoring defined significant cardiac arrhythmia included 34 cases of long QT syndrome, which accounted for 24.3% of all significant Holter outcomes. Other significant findings (Table 3) included 32 cases (23.0%) frequent supraventricular or ventricular ectopy, 20 cases (14.4%) supraventricular or ventricular ectopy in bigeminy or trigeminy, and 14 cases (10.1%) of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia etc.

The predictive patient characteristics associated with significant Holter outcome or cardiac arrhythmia are summarised in Table 1. Using Chi-Square test, it was found that patients who were aged more than 80 years old, with chronic comorbidity, with hypertension, with ischaemic heart disease, with atrial fibrillation or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation were statistically significant associated with significant cardiac arrhythmia (p < 0.05). The odd ratio (OR) of patients aged more than 80 associated with significant Holter outcome was 7.27 (95% CI: 2.01 to 26.29). The OR (95% CI) of hypertensive patients and ischaemic heart disease patients associated with significant Holter outcome was 1.83 (1.17 to 2.88) and 10.87 (1.34 to 87.98) respectively. Multivariate analyses by stepwise backward regression procedure were applied to determine the patient characteristics associated with significant Holter outcome. The factors including age, concomitant of chronic disease, hypertension, or ischaemic heart disease and patient’s presenting symptoms including dizziness or combined were included for analysis. The final fitted model revealed that patient age and combined presenting symptoms were significantly associated with significant Holter outcomes. (Table 5) Discussions FM & GOPD of Kwong Wah Hospital is a primary care clinic affiliated to a regional hospital. Patients can register as walk-in basis consulting for their cardiac related symptoms. The attending primary care doctor can book Holter monitoring directly at Cardiac Unit of the hospital. The overall diagnostic yield of Holter monitoring reported in the literature was 1-20%.7,8,9 However, it strongly depended on the population studied.10 The number of significant Holter findings in our series was 43.7%, which was remarkably higher than local and international non-primary care studies3,6. Palpitation Palpitations are non-specific and represent one of the commonest symptoms in general medical settings, reported by as many as 16% of patients.11 Establishing the cause of palpitation may be difficult because historical clues are not always accurate.12 Discerning cardiac from non-cardiac causes is important, given the potential risk of sudden death in those with an underlying cardiac aetiology. Holter monitor is usually used to determine the cause of palpitation; however, the yield of this instrument is low especially in patients whose symptoms occur infrequently, i.e. 2-20% of the Holter outcomes are significant.2,13-16 Syncope and Presyncope Syncope and presyncope presenting in the community can be a challenging task in diagnosis.17 Patients with syncope undergo extensive and repeated investigations without a diagnosis. Holter monitoring are done for almost all patients with syncope, despite the fact that, in several studies, only 2% to 4% of tests results in symptom-rhythm correlation.9,18,19 Arrhythmia are the most common cardiac cause of syncope, and include bradyarrhythmias (such as sinus node dysfunction), atrioventricular conduction disorders, atrial fibrillation with slow or rapid ventricular response, and ventricular tachyarrhythmias.9,20,21 In our study, only 6 cases (1.9%) of Holter recording were indicated for patients with syncope. The proportion is very low as compared to a hospital or emergency department setting. It is likely that those patients presented with history of syncope or presyncope have already been referred early by the primary care doctor to a specialist for further workup and treatment. Dizziness Dizziness is very common in the primary care and also is one of the most common symptoms referred to neurology and otolaryngology practices.22,23 In the review of 10 studies, dizziness was attributed to a cardiac arrhythmia in 1.5% of study population.23 In our study, 16 cases (5.0% of total) of Holter monitoring were indicated for dizziness. 4 patients (25%) had significant cardiac arrhythmia. As the number of cases was too small, it was difficult in making comparison with other studies. Limitations Patients with symptoms related to cardiac arrhythmia are not all included for Holter monitoring, and secondly, arrangement for Holter monitoring was ordered by all doctors in the department, therefore a patient selection bias cannot be excluded. This study involves patients from one primary care clinic only, it is uncertain whether this study group represent all patient population of primary care setting or not. The outcome measure of our study focus on yield of Holter monitoring, the correlation between symptoms and diagnosis was not investigated. It is uncertain whether the Holter diagnosis has causal relationship with patient’s presenting symptoms or not.

Conclusions In this study, palpitation was the commonest presenting symptoms for which holter was arranged. Significant cardiac abnormalities were detected in 43.7% of Holter monitoring which required referral to specialist for further management. Advanced patient age and patient presented with combined symptoms correlated with significant cardiac arrhythmia. Lap-kin Chiang, MBChB (CUHK), MFM (Monash) Lorna Ng, LMCHK, MPH (CUHK), FHKCFP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Correspondence to: Dr Lap-kin Chiang, Family Medicine & General Outpatient Department, 1/F, Tsui Tsin Tong Outpatient Building, Kwong Wah Hospital, 25 Waterloo Road, Mongkok, Kowloon, Hong Kong References

|

|