|

April 2001, Volume 23, No. 4

|

Discussion Paper

|

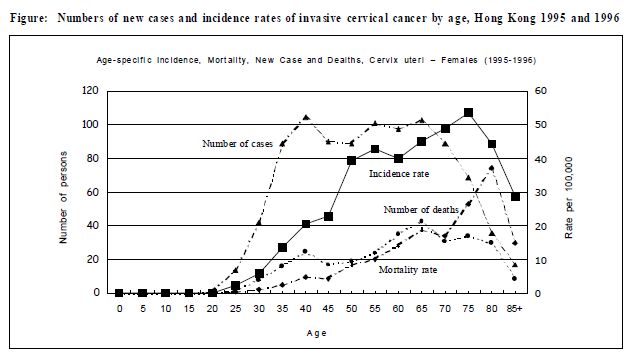

Controversies in cervical cancer screeningJA Dickinson 狄堅信 HK Pract 2001;23:149 - 152 Summary There are disagreements about cervical screening, based on changing knowledge, and different views of the evidence. Important areas of uncertainty and dispute are briefly described, and a conservative approach for family physicians is described, intended to provide g reatest benefit for individual patients with least risk of causing harm, both physical and psychological. Because of the family physician's role as "broker " of health care, we must understand the role of others, especially pathologists and gynaecologists, and be able to appraise whether they are offer ing a good ser vice. We must offer a ser vice that encourages women, particularly those who are uncertain about the discomfort of pelvic examination. To reduce morbidity and mortality from this largely avoidable disease Hong Kong needs to screen more of the older women who are currently unscreened. Family physicians must actively participate in this process. 摘要 基於知識不斷更新,以及對例證的不同闡釋,進 行宮頸癌普檢的方式仍未達到一致共識。本文簡述有 關爭議,並提出一個適合家庭醫生採用的穩重方案, 力求為病人帶來最大裨益,又不會使她們在心理和生 理上造成影響。作為家庭醫生,我們會肩負轉介病人 的工作,因此需要認識其他專科,尤其是病理科和婦 產科同僚的重要性,和能評價他們的醫術。我們應該 鼓勵婦女接受婦科檢查。同時需要積極地推介子宮頸 塗片檢查,對年紀較大,而從未接受過檢查的婦女尤 其重要,從而減低宮頸癌的發病率和死亡率。 Introduction Cervical screening is one of the oldest cancer screening methods, and while it has never been subjected to a randomised controlled trial to accurately test its worth, evaluation of its full application shows it can decrease invasive cancer by 90%, thus cutting life time risk in Hong Kong women from 1 in 70 to 1 in 700.1 However, there are several controversies about its use. When should women start screening? Cervical cancer is currently believed to be a sexually transmitted disease, caused by particular sub-types of the papilloma virus. Thus women are eligible for screening if they have been sexually active. Some American recommendations suggest that all women over the ageof 18 should be screened.2 Evidence for cancer risk in virgins is lacking, and fewwould findit acceptableto undertakesmears on women not yet sexuall y active. Ignore these recommendations. Some gynaecology texts give the impression that cancer risk is high in young women, and indeed it is true that the greatest number of cases occur in the 40 to 45 years age group,because there are fewer old women. However, when numbers are converted to rates, the incidence risesonly very slowly, and continues to a peak at 75-79, so when you have an elderly woman in your practice she is actually at much higher risk than young women (see Figure).

In the years after they start sexual activity, young women may get several infections by papilloma viruses, which are diagnosed as squamous intraepithelial lesions. Like other warts,most such infections are overcome by the immune system, and the lesions regress.3 It is not yet clear how to predict which infections will develop into cancer, though fortunately this process usually takes a long time. Thus there is little need to rush into early smearson women who have only recently started sexual activity, since these transient lesions do not need treatment. It is now clear that young women have no greater risk of rapidly developing disease.4,5 Consequently we should focus our attention on older women more than young. We should start screening about five yearsbefore the rise in incidence, so there is little point in starting screening until at least a few years after sexual activityhas commenced.6 High risk groups Sadly there is an impression that women who get cervical canceror even smear abnormalitiesare more likely to have multiple sexual partners. It may bemore likely that the husband has been, acquiring the virus and bringing it home to his partner, asmay occur with any other sexually transmitted disease.7 Thus history of sexual activityfromthe woman may miss the real risk factor. Smoking does increase the risk of cervical cancer: anotherargument againstthisanti-socialhabit. Consequently smokers should be screened, but since there is no evidence that cancer advancesmore rapidly in thosewith higher risk, there is little need to screenmore frequently, only to ensure that it is done. Interval for repeat smears Some doctorsmay be surprised that theCancer Fund is suggesting women should have a smear every three years instead of annually. Thisrecommendation is in linewith the vastmajority of countries around theworld, including those with the most successful screening programs that produce greatest reductions in invasive cancer incidence. The Hong Kong Collegeof Obstetrics and Gynaecologistsendorsed the three-year interval in December of 1999.8 Nowonly a few American groups still recommend annual smears.2 Many doctors are worried by the idea of long intervals between tests, fearing that the low sensitivity of individual testsmay causemissed cases. This arises in part because of misunderstanding. Pap smears are not a direct screening test for cervical cancer. Cytology detects Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions,SIL, which correlate with the histological diagnosis ofCervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia [CIN]. Only a small proportion of these progress to invasive cancer over a long time span, estimated as 8 to 15 years.9,10 While sensitivity for CINis low,it isbetter for higher-grade lesions, and a programof repeated tests hasbetter performance than each individual test.11 Thus the value of regular three-yearly screening is to give several opportunities for detection before dangerous development occurs. Even in the best of hands, cervical screening cannot be perfect, but it can prevent over 90%of cervical cancers (far better than any other cancer screening program). The uncommon adenocarcinomas of the cervix cannot bereliably detected by smear test. Some argue that the only reason for recommending triennial smears is cost. They think that while government should be concerned about that, individual doctors need not, and patientswho can afford the tests should have themmore often. However, even those who can ignore cost should be aware of the potential for harm in terms of psychological burdenwhich must be set against the potential benefit of early detection.12 Pap smearsare a screening test,not diagnostic. Because ofuncertainty, pathologistsmay recommend colposcopy and biopsy to ensure there is no problem.13 This may occur in 1%to 5%of smears, depending on the cut-off used. A woman who has annual smears trebles her risk of getting such a false positive,while improving her chance of having a cancer detected by perhaps1.5%of the lifetime risk. A positive smear result leads to facing the possibility of having cancer:which has long-lasting psychological effects in many women.14 Treatments, even for non-cancer lesions may produce physical complications such as cervical stenosis, and haematometra, while the healing process after laser or other forms of ablation may take a long time.15 On balancethereforemostexperts groupsaround theworld have concluded it is better for women to have Pap smears at intervals longer than yearly. What should we ask of our laboratories? If smears are examined by a good laboratory, then many researchers have shown that the duration of protection from invasive cancer after a normal smear is at least 5 years.11 Quality control is important as in all laboratory tests. You should know whether your laboratory has a high standard. They shouldreport using the recent modification of the Bethesda system,withclear indicationsofwhatfurther follow-up of abnormalities should be done. They should inform you about their staff training, the quality control systems they use, both internal and external and that they participate every year. They should regularly give you feedback about the quality of your smears: not because of any problems, but because everyone needs feedback to maintaintheir quality. Itwould beideal if they alsoinformed you about their overall results, which should be about 95% of smears reported as normal, and 0.5 to 1%reported as high grade lesions. Ideally laboratories should validate their cytology results with the outcomes of colposcopy, but this is difficult in Hong Kong, since gynaecologists often refer biopsiesto different laboratories fromthose thatreported the cytology. Endocervical cells Many doctors worryabout the presence of endo-cervical cells, but you should be sure that you took the smear from the right place. If so, the proportion of your smears containing endo-cervical cells is a marker of your overall smear adequacy, and should be 75 to 85%depending on the age group of your patients. These cells are often absent in older women, and individual smears need not be repeated since a woman whose smear lacks such cells is actually at lower risk for developing cancer over the next few years.16 Pelvic examination Wewere all taught thatwemustdo apelvic examination as well as the smear. Accurate bimanual examination skill is difficult to develop and needs to be maintained, but there is limited evidence that such examinationsdetect ovarian or uterine cancer. Therefore it is not an essential part of the procedure, but itis uncomfortable forwomen,andmanymay be put off by this component. Many women find the process of smear collection unpleasant:17,18 quoted by Straton19 "an extreme invasion of personal space" " The pelvic examination is one of the most common anxiety producing medical procedures: it is certainly physically uncomfortable, embarrassing for some, and the nature of the position strikes directly against traditional values such asmodesty and respectability" Fear of embarrassment isimmediate, andmay begreater than fear of cancer some time in the future. It is therefore hardly surprisingthatwomen feel inhibited aboutasking for the procedure. We have to encourage them, and help them overcome these barriers.We haveto overcome ourdiffidence about asking, in order to help women. Taking cervical smears isa simple procedure,within the capabilities of any reasonably intelligent person. In some countries laboratory technicians take them. Women prefer to go to smears-takers who they can trust, and who will do the procedure kindly, less uncomfortably, and respectfully. We asdoctorsmust showthat we can do thisprocedure well: not just technically, but considering the women's feelings. Conclusion More work is needed to find out the best ways to get high screening rates in Hong Kong. This will most likely require informing women, and changing the behaviour of both women and doctors. Are doctors ready for this challenge? Key messages

J A Dickinson, MBBS, PhD, FRACGP

Professor of Family Medicine, Depar tment of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese Univer sity of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Pr of J A Dickinson, Depar tment of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese Univer sity of Hong Kong, 4/F, Lek Yuen Health Centr e, Shatin, N.T. , Hong Kong.

References

|

|