|

April 2001, Volume 23, No. 4

|

Discussion Paper

|

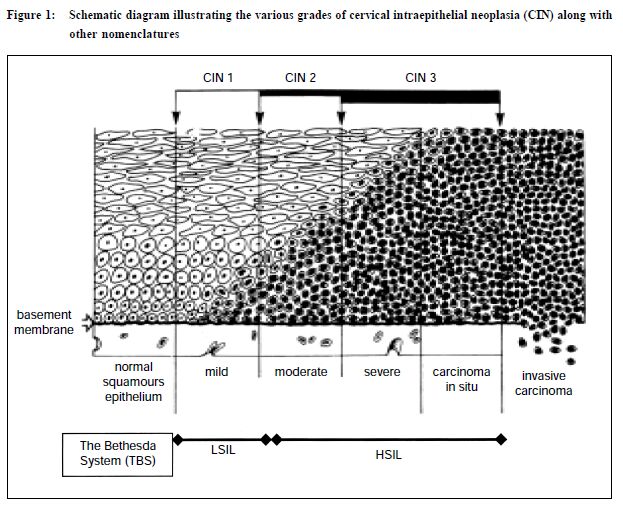

The cervical Pap smear test: the pivotal role of the laboratoryA R Chang 陳志強 HK Pract 2001;23:154-163 Summary This review highlights the pivotal role of the pathology laboratory in ensuring the continued success of Pap smears in cervical cancer prevention. It documents how the pathologist can influence the entire series of events from specimen collection, the laboratory processing, reporting and the provision of advice to the clinician. The use of new technology and steps to enhance laboratory standards are also discussed. 摘要 本文強調子宮頸塗片病理化驗對防癌的重要性。 病理學家的意見可以影響包括取樣、化驗程序、報告 和向臨床醫生提供建議等一系列過程。文章也討論到 提高化驗水準的新科技和方法。 Introduction The Pap smear test was named after George Papanicolaou who devised the procedure over 70 years ago, after he found cancer cells in some samples collected from the vagina for investigating hormonal changes. Subsequently, it has proved to be one of the most effective procedures for the prevention of cervical cancer.1,2 This favourable situation is possible because most cervical cancers start with a preinvasive and curable stage that normally progresses slowly over a period of several years before invasion occurs. A welltaken Pap smear examined by a good laboratory can detect the various grades of precursor lesions (Figure 1) and with appropriate treatment, cancer is prevented from developing. Countries where a well-organised Pap smear screening programme is in place have a very low cervical cancer rate.1,2 A group of experts concluded "that with the exception of stopping the population from smoking, cervical cytology screening is the only proven public health measure that significantly reduces the burden of cancer today".3 Despite being an excellent test it is not totally foolproof and there is a significant false-negative rate. This means the test fails to detect a subsequently proven disease and can be due to a number of factors, including the nature and location of the area of dysplasia, faulty sampling and laboratory error. It has been estimated that faulty sampling by the clinician can account for over 60% of false-negative smears, laboratory factors are responsible for the remaining cases.4

The role of the laboratory

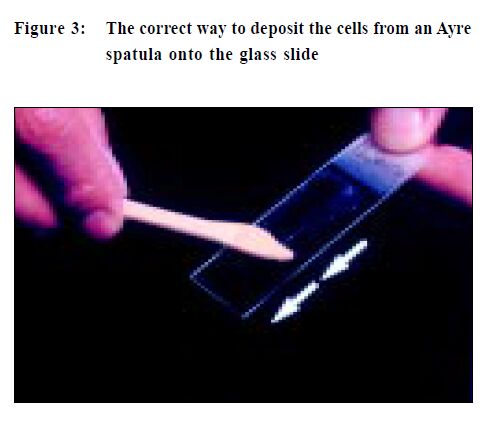

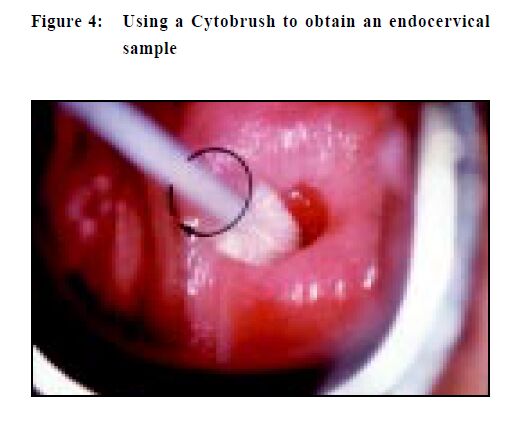

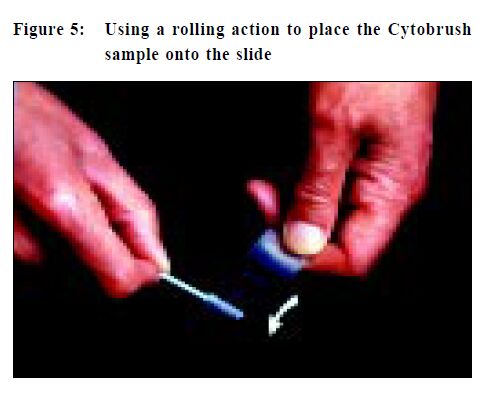

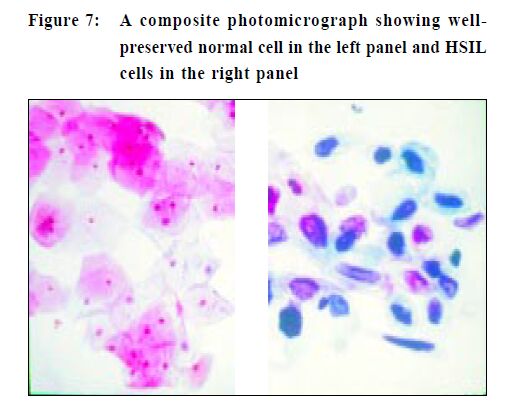

The first step is to label the glass slide with adequate patient identification, (do it before you take the specimen) and when overlooked can result in a potential medico-legal problem. Lubricant should not be used to ease the insertion of a speculum as the jelly can obscure cells and a lesion may be missed. It is better to use tepid water to both lubricate and warm the speculum, a much more patient-friendly option. Taking a Pap smear is a "blind procedure" as the clinician is not able to specifically sample areas of abnormal tissue.5,6 To obtain an optimal specimen the sampling implement is swept 360 degrees once around the entire ectocervix (Figure 2). This is important as the precursor lesions of cervical cancer are invisible to the unaided eyes and are also asymptomatic. When placing the specimen onto a slide, a rapid stroking action should be used and not a circular emulsifying action as this will crush cells and also disrupt cell groups that can aid diagnosis (Figure 3). If a Cytobrush (Figure4) is used to sample the endocervix, the cells are deposited on the slide with a rolling motion (Figure 5).5 Air-drying cellular changes make microscopic interpretation very difficult and an abnormality may not be identified (Figures 6 and 7). That may happen if you delay immersion of the slide in 95% ethyl alcohol, or application of spray fixative. It is better to place the cytobrush sample on a separate slide and the clinician should take a second sample with a wooden sampler from the ectocervix. A Cytobrush sample alone constitutes an inadequate examination. As the brush can induce some bleeding it should be used after the ectocervical sample as blood can obscure diagnostic cells and a lesion remain undetected.5

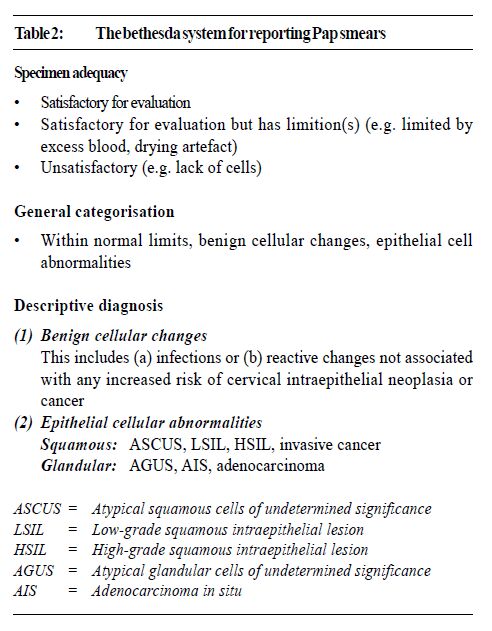

In women of child bearing age, adequate samples should have endocervical and/or metaplastic squamous cells to indicate the transformation zone (TZ), the region where the majority of cancer develop, has been sampled.7,8 In older women with migration of the TZ into the canal, endocervical cells may be absent. A good smear should have least 10% of the slide covered with well-preserved and well-visualised squamous cells. In Hong Kong the Bethesda System (TBS)9 of reporting Pap smears is widely used. This includes comment on the adequacy of the specimen which is an integral part of the report. Thus laboratories have a duty to rectify problems by informing clinicians of their smear quality. Finally, all smears should be accompanied by adequate clinical data. The minimum information should include the patient's age, LMP, previous obstetrics and gynaecology history, hormone therapy and a brief record of any clinical findings. This information can help increase the sensitivity and reliability of the laboratory interpretation of the Pap smear, especially in cases where the findings are uncertain. The examination of Pap smears is a labour intensive process. It can be boring and yet requires full attention. Screeners are usually medical technologists with additional training in cytology and certification by the International Academy of Cytology. A smear can have more than 300,000 cells. The initial screener has the task of identifying abnormal cells, which are marked and referred to the pathologist for final assessment before reporting. A good screener will take 5-6 minutes to examine a slide and in an 8-hour day it may be possible to examine 12 per hour and theoretically 96 slides daily. However, fatigue can set in and a good laboratory ensures screeners have regular breaks. A target of 50 Pap smears is an acceptable workload, otherwise abnormal cells are not detected, with disastrous consequences. This was vividly demonstrated in accounts of shoddy laboratories in the USA that paid screeners by the number of cases examined but had unacceptably high falsenegative rates. The revelations created a public up-roar which resulted in congressional hearings and enactment of the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988.10 The regulations laid down the maximum number of slides that could be screened daily by technologists. Furthermore, all abnormal smears must to be examined by a pathologist before reports were issued. In addition, laboratories were mandated to re-screen 10% of their negative Pap smears. Cytopathologists and cytotechnologists are monitored by the Centre for Disease Control. These stringent regulations resulted in the closure of many second-rate laboratories.10 In Hong Kong most laboratories use The Bethesda System (TBS) for reporting Pap smears. This nomenclature is the outcome of two workshops at the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, Maryland) in 1988 and 1991.9 This has replaced the Papanicolaou Classification in which cytological reports were designated Class I (normal) through to Class V (conclusive for malignancy), which no longer reflect our understanding of cervical and vaginal neoplasia. In addition, it was not compatible with the diagnosis in biopsy material while abnormal but benign entities were not adequately catered for. Moreover as a result of modifications the various classes had a different meaning when used by various laboratories. TBS also lends itself to computer entry because of its coded format. Briefly TBS covers specimen quality and adequacy, general categorisation of cytological findings and a descriptive diagnosis of any abnormality. The lesions that are called Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) encompass cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade one (CIN I) and human papillomavirus (HPV) lesions while High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (HSIL) include CIN II and CIN III lesions (Figure 1 and Table 1). In Table 2 the major elements of the TBS are listed.

In the Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance (ASCUS) category the cellular changes are not clear-cut and a more specific diagnosis cannot be made. It is not synonymous with previously used terms such as atypia, benign atypia, inflammatory atypia, or reactive atypia. When a diagnosis of ASCUS is used the laboratory should attempt to qualify it in the following manner, such as ASCUS favour SIL or ASCUS favour reactive changes. It is legitimate to use ASCUS if sparse, poorly preserved cells indicate a SIL but a definite diagnosis is not possible. The ASCUS rate for a low risk population should be less than 5% of results and for high risk populations around 2-3 times the SIL rate. If a laboratory has a SIL rate of 2% then the frequency of ASCUS should not exceed 6%.9 The diagnosis of ASCUS should be based on rigid criteria and it should not be used to "lump" all cases with minimal cellular abnormalities. It has been shown that women with ASCUS are at risk of harbouring a more advanced lesion. In one study 28% of 2765 women with ASCUS had biopsy proven SIL and 10% had a CIN II or higher grade lesion.11-13 Thus women with persistent ASCUS need to be further investigated such as with colposcopy. Reports from good laboratories include recommendations such as repeating a smear or referral for other investigations. Clinicians and pathologists should communicate regularly so that what is stated in a report is clearly understood. The need for optimal laboratory standards

Internal quality assurance programmes include the monitoring of all aspects of specimen processing within a particular laboratory. This encompasses continuing education, training, review of procedures and their implementation, re-screening of a proportion of normal smears and various auditing procedures. External programmes entail the evaluation of slides sent from an external agency and the return of the diagnosis within a specified time. At the time of writing only one pathology laboratory in Hong Kong has been accredited by a dedicated medical laboratory assessment agency and others are in the process of doing so.14 A laboratory is accredited if it has a system that allows high quality laboratory work to proceed. A process of formal evaluation of a laboratory by an unbiased external testing agency, such as National Association of Testing Authorities Australia (NATA) or the College of American Pathologists (CAP) is an essential step to ensure Pap smears are evaluated to the highest possible standard. During an accreditation inspection, all aspects of laboratory operation are scrutinised; not just how tests are performed but also the qualification and experience and supervision of staff, methods, reporting practice, record keeping, and quality control programmes (internal and external), staff training, continuing education and safety.14-16 In the inspection of a laboratory for accreditation, a peer review system is used and a team of outside expert pathologists and technologists carry out the evaluation. In some countries, accreditation is mandatory if a laboratory is to receive insurance and government funding.15 In order to improve cytology standards, an important and regular exercise is to correlate the cytology diagnosis with relevant histology. Thus having cytology and histology specimens in close proximity facilitates this review process. The close interplay of histopathology and cytology is well illustrated in the contemporary management of any woman with a significantly abnormal Pap smear. The cervix will have a normal appearance when examined with the unaided eye and in addition, the patient usually has no symptoms. A colposcopic examination allows the lesion to be identified, and during this procedure directed biopsies are taken for histological verification (Figure 8). The biopsies are important and if the pathologist can exclude invasion, simple ablative therapy is usually sufficient for satisfactory treatment. In contrast, if invasion is detected more extensive surgery will be needed, with or without more biopsies being taken to allow histological confirmation of the clinical diagnosis.6

A Cone biopsy is seldom used to treat the precursor lesions of cervical cancer, especially in younger women. Excessive removal of normal tissues can result in either cervical stenosis or incompetence and both are undesirable, especially if future pregnancy is contemplated. Pathologists also have a pivotal role to play in the management of patients with more advanced disease requiring major surgery. The meticulous examination of the radical hysterectomy specimen and associated lymph nodes is crucial for optimal patient management. The laboratory role in improving the Pap smear specimen A major problem with the conventional Pap smear is that only 20-30% of cells are transferred onto the slide and the rest are discarded with the sampling device.17 Consequently, there is ample scope for a false-negative smear result. Some methods for "optimising" the Pap smear specimen will now be briefly discussed.

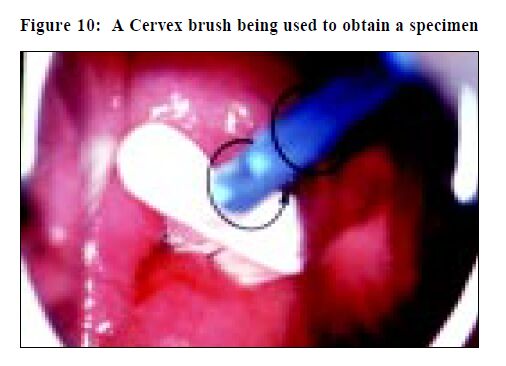

The wooden sampler that is still widely used in Hong Kong is a modified version of the one invented in 1947 by Ernest Ayre, a Canadian gynaecologist.18 To improve cell collection other devices have been developed and include the Cytobrush and Cervex brush (Figure 9). An adequate Pap smear can be obtained by using the modified Ayre's spatula to collect an ectocervical sample and a Cytobrush to obtain an endocervical component. This generally results in two slides, which increases the laboratory workload substantially. The Cervex brush (Figures 10 and 11) can collect a comparable sample to that obtained by using both a wooden scraper and Cytobrush, and only requires a single slide.5,19

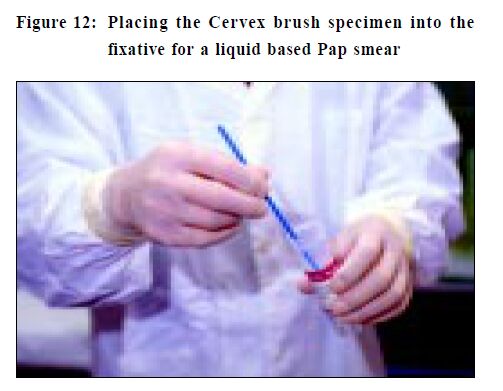

Previously, liquid based preparations had been successfully used for fine needle aspiration specimens, sputum samples and body cavity fluids. The specimen is collected in a similar way to a conventional Pap smear but instead of being smeared onto a glass slide the sample is rinsed into an alcohol-based solution (Figure 12). This solves the problem of drying artefact in cells, which is often present in poorly fixed conventional smears. Good quality specimens that contain cells in a monolayer are now prepared in the laboratory.20 Studies have shown liquid based samples have sufficient cells to make a diagnosis and the detection rate is as good or better than conventional smears.21 Laboratory examination is faster because all the cells are located within a 13-20 mm diameter circle and obscuring material such as blood, mucus and inflammatory cells are removed during processing.20-22 Any unused material can be used for ancillary investigations, such as human papilloma virus (HPV) testing. The main disadvantage of the liquid based Pap smear is the higher cost. Smears have to be obtained with a more expensive sampler such as the Cervex brush because cells adhere to the wooden Ayre's spatula and are difficult to transfer into the fixative fluid. Other costs include the laboratory processor, liquid fixative, special slide and single-use filter. However, costs should decrease with wider use.

Computer technology to help improve Pap smear screening The examination of Pap smears is very labour intensive and computer-based devices are available to help improve manual screening.23-27 One system in Hong Kong (PathFinder ® ) consists of a computer and a small monitor that are attached to the microscope. When the screener examines a smear, a "map" is produced. If the screener has a tendency to overlook areas on the slide this can be observed and corrective action can be taken. The "map" can be recorded and retrieved for later review. The system also allows the electronic tagging and labelling of any abnormal cells identified and these can be retrieved for examination at a later date. Quality assurance functions, such as the correlation of previous smear and biopsy results can also be undertaken. Screening efficiency can be improved by up to 15% by the use of these computer linked devices.23 Recruiting more women to have Pap tests may overburden existing laboratories and there is a shortage of experienced cytotechnologists. Employing one of the new automated cervical screening instruments, such as the AutoPap® Primary Screening System (Figure 13) may reduce problems. Use of this instrument may increase the overall accuracy of the cervical screening process as well as showing the potential for significant improvements in laboratory productivity.6-9 Any primary screening system utilised must have high sensitivity so that cancers and precursor lesions are detected. In addition, high specificity is important if laboratory and clinical productivity is to be optimised. Other important requirements are the ability to identify inadequate samples, the location of abnormal cells for subsequent manual examination, and increased throughput of cases (compared to manual screening) at a reasonable cost.20-25

The AutoPap® uses a high-resolution scanner and a highspeed video microscope to obtain cell images from conventional Pap smears. The images are digitised and the data processed with image interpretation software. Specially designed algorithms to recognise, analyse and identify cases that have the highest probability of containing abnormal cells. Slides having the lowest probability of being abnormal can be safely reported as "within normal limits" (WNL) and need no further manual review by a cytotechnologist. Slides with a higher probability of abnormality require manual cytologist screening. Additional quality control rescreening is performed on the highest probability slides deemed WNL on initial manual screening.26 Currently, the AutoPap® is the only instrument approved by the United States Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for primary screening. Outside the United States of America and including Hong Kong, up to 50% of slides are being archived with good performance.28 In addition to overall slide classification, the instrument produces a printed map of the slide (PAPMAP® ) that contains up to 15 circles, each referred to as a field of view (FOV).In abnormal cases the FOV's are highly likely to contain individual abnormal cells. Accompanying each slide map is information on specimen adequacy, the presence of endocervical cells, the degree of obscuration by inflammatory cells, and the overall ranking of the case. The Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH) uses an AutoPap® Primary Screening System. An experienced cytotechnologist takes approximately 5 minutes to screen a Pap smear.29 The screening time could be substantially shortened if an accurate cytological diagnosis was obtainable by looking only at the FOV's that the instrument identified as containing abnormal cells, without the need to screen the entire slide. Studies done at the PWH show that the screening time for Pap smears can be halved by using the AutoPap® system. The instrument is also able to examine liquid based Pap smears and this will be undertaken in the near future. Conclusion High quality laboratory services are essential for the evaluation of Pap smears, especially if the women of Hong Kong are to reap the full benefits of this simple but effective test. Laboratories should give all Pap smear takers regular feedback on the quality of their smears and this is required for accreditation. Laboratories have a duty to offer the best service and one way of measuring this is to be accredited by a recognised specialist agency. New technologies may improve the test but using them may direct screening money to pay for these items and hence depriving those who have never been tested the chance of having a Pap smear. Despite the emergence of new techniques, the conventional Pap smear when well taken and evaluated by a competent laboratory is still the "best" and "most cost-effective" test for cervical cancer prevention.30 Key messages

A R Chang, MD(Otago), Dip Clin Path, FRCPA, FHKAM(Pathology)

Professor in Pathology, Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr A R Chang, Chief of Cytopathology, Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong.

References

|

|