|

April 2001, Volume 23, No. 4

|

Editorial

|

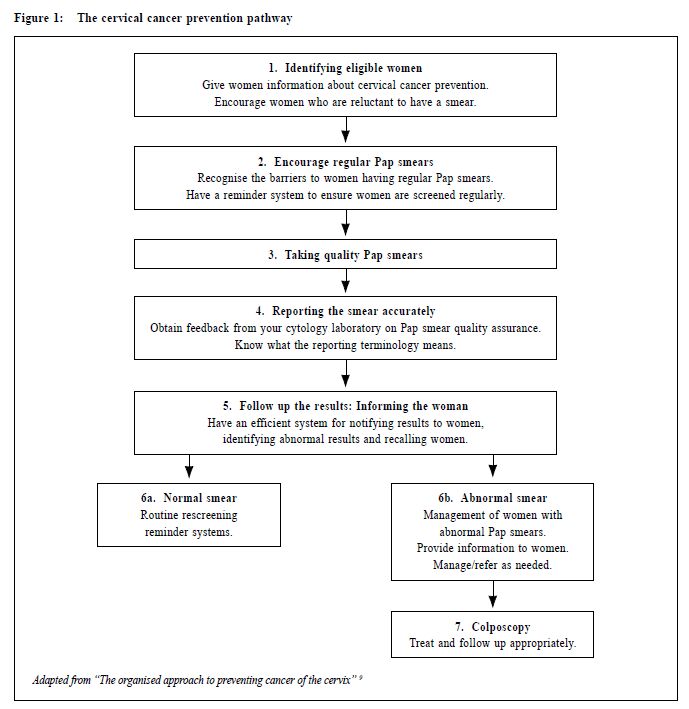

Family physicians' roles in cervical cancer screeningJ A Dickinson 狄堅信 Once more this year, the Hong Kong Cancer Fund will be running a cervical screening publicity campaign during the month of May. Invasive cervical cancer is the fourth commonest women's cancer in Hong Kong, and would affect as many as one in 60 women if screening did not occur.1,2 We should think of cervical smears not as simply a test, but as a programme. The prevention pathway incorporates the steps shown in Figure 1. To be effective, all must be completed properly, and family physicians have a major role in most of these steps.

This editorial introduces three articles in this issue which emphasise different aspects of the screening process, but we must remember, as Muir Gray points out, that "screening programmes . . . require an obsession with quality to be effective . . .".3 We must ensure our part is done well, and that we link with others who do so too. Identifying eligible women The greatest problem in cervical screening is that older women with low levels of education who are at highest risk are least likely to have had a smear. Many have not even heard about them. Therefore our greatest effort should focus on enrolling into the programme women who have never had a smear, or had one more than three years ago rather than repeating annual smears. Studies in Singapore, New Zealand and Australia show that many women find it difficult to initiate screening.4,5 While cost may be a barrier for some, uncertainty and unwillingness to ask their doctors to give them a gynaecological examination is important.4,6 In Australia the most important factor that encourages women to have Pap smears is being asked by their doctor7 and it seems likely this is the case in Hong Kong too. The publicity materials will inform women about who should get a smear, and urge those who have never had a smear, or one more than 3 years ago to attend appropriate sources of care, including family physicians. You can put up posters in your waiting room or even in your consultation room that will remind women (and you) to ask about Pap smears. Perhaps your staff can hand out a leaflet to eligible women when they come in for other reasons. Encourage regular Pap smears Our records should have a reminder about women who are eligible so we can ask them to make an appointment for a smear. They should know that regular three-yearly smears are the key to successful prevention. The campaign will assist with this. Taking a quality smear Trained family physicians should provide Pap smears as part of their services. Some doctors still refer patients to gynaecologists or special clinics. This is a pity, because it places extra burden and costs on the women, and decreases the chance that they will attend for a smear. To take a good cervical smear is simple. Regrettably many doctors did not have enough opportunity to learn this skill properly during their training, but you can learn relatively easily. The article in this issue by Dr Fan describes how. Since doing a smear takes more time than a standard consultation, you may prefer to arrange a specific separate consultation during the quieter periods of the week, for an appropriate fee. Reporting the smear accurately Smears must be sent to a good laboratory, which has well-trained staff, using the Bethesda system and clear recommendations for action. They should give you feedback, so you know how well you are doing your smears. Professor Chang gives more detail. Follow up the results: informing the woman We must inform all women about their result, whether positive or negative. It is not adequate to tell patients they need not worry if they do not hear from you. When traced back, many women with invasive cancer had an abnormal smear whose result was never communicated. Thus all smear results should be positively communicated, and a record made of the fact. We must develop registers to keep track of tests sent away to ensure all results are returned. What we tell women is important: we should give a positive message that a normal smear means a low risk of cancer in the next 3 to 5 years.8 With an interval of three years, many people forget and may not return. Therefore, they need reminder systems. It is easy to set up your own system, with a simple reminder card on which women can write their own name and address so you can mail to them in three years time. Alternatively, the Hong Kong Cancer Fund has an e-mail reminder system that anyone can use. Further investigation and management of positive smears Most of us refer abnormal smears to a gynaecologist or clinic that is experienced in this field, and has colposcopy facilities. This is a specialized field, and those we refer to should have extra training in this field. They should use a systematic approach as described by the article by Dr Lam. Family doctors are one of the most important links in an effective cervical screening programme so I hope all will participate in the campaign, putting up posters about cervical smears, educating staff to encourage appropriate patients and re-organising practice systems to encouraging women to have smears, tracking their results and reminding them to return for repeat smears. If the campaign is successful fewer women will need treatment for invasive cancer, and its effect will be reduced accordingly.2 A group of us will be evaluating this programme, to understand its effects, and work out how to be more effective in future. If you are selected for one of our surveys, please help us in this process. Any suggestions for improvement will be greatly appreciated by the Hong Kong Cancer Fund.

J A Dickinson, MBBS, PhD, FRACGP

Professor of Family Medicine, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Prof J A Dickinson, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 4/F Lek Yuen Health Centre, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong.

References

|

|