|

April 2001, Volume 23, No. 4

|

Update Articles

|

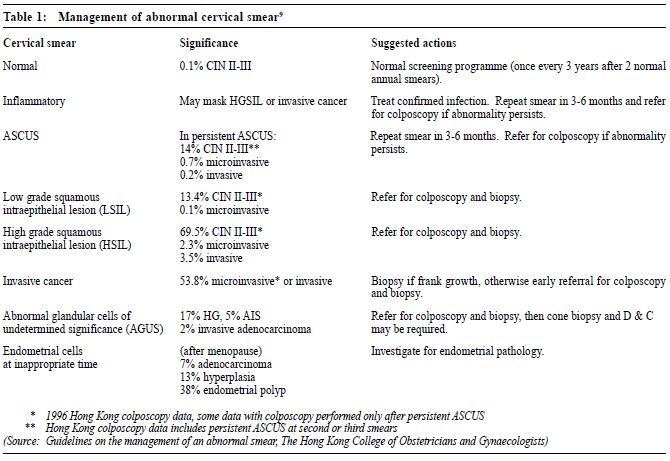

Cervical cancer screeningK F Tam 譚家輝, H Y S Ngan 顏婉嫦 HK Pract 2001;23:140-143 Summary In Hong Kong, cervical cancer is the 4th commonest malignancy in females. Cervical cytology screening is effective in reducing the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer. Women should have regular cervical smears from the time they start to have sexual activity until they reach the age of 65. A cervical smear should be taken and handled properly, so that the sensitivity of the test will not be affected by the quality of the smear. Most of the laboratories in Hong Kong are now using the Bethesda System to report cervical smears. In order to manage patients properly, doctors should be familiar with this classification. 摘要 子宮頸癌是香港女性最常見的癌病中佔第四位。 利用子宮頸脫落細胞防癌塗片檢查可以有效地降低其 發病率和死亡率,所以婦女從有性生活開始至六十五 歲都應定期進行子宮頸細胞檢查。檢查的準確性取決 於正確的取樣和處理子宮頸細胞。香港大部份化驗室 均採用Bethesda System ,因此醫生也應認識有關方法 和分類,以便替病人作出適當治療。 Introduction According to the Hong Kong Cancer Registry, there are about 500 new cases of cervical cancer and 150 deaths from this disease every year. Cervical screening programmes have been running in Hong Kong for many years. Although there has been a decrease in age standardised incidence, cervical cancer remains one of the commonest malignancies in females. The existence of a long latency period between the precancerous stage and invasive cervical cancer formed the basic justification for cervical cancer screening. Cervical cytology screening decreases the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer.1 Primary care is central to the overall success of the cervical screening programme. Family physicians are in a unique position to invite women for a smear test, to take smears, to ensure that abnormal smear test results are followed up, and to check on reasons for non-attendance.2 Who should be screened? Women are advised to have cervical cytology screening when they become sexually active until the age of 65. However, a woman over the age of 65 who has never had a cervical smear should also be screened. The age limits for cervical screening have been a subject of debate. According to the recommendation of the Intercollegiate Working Party in 1997, the cervical screening programme in England and Wales is targeted at women between 20 and 64 years of age.3 If previous cervical smears have been consistently normal, women can be discharged from the screening programme after the age of 65. Women having risk factors for cervical cancer and who have not had a cervical smear before, should be encouraged to have a cervical smear. Frequency of cervical smear The reduction in the cumulative incidence of cervical cancer is 93% with annual or biannual screening interval, 91% if performed every 3 years, 84% if performed every 5 years and 64% if performed every 10 years. Women having normal cervical smears on two consecutive years could have the interval spaced out to 3 years without reducing the chance of detecting cervical cancer, and at a lower cost.4 However, in high-risk patients like those who are immunosuppressed or those who have a history of abnormal cervical smear, annual screening is advised. Taking a smear Several methods, such as cervical cytology, cervicography and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) typing, are used to screen for cervical cancer. Cervical cytology remains the gold standard for cervical cancer screening since this is the only method with established effectiveness. The sensitivity of the cervical smear depends greatly on the quality of the smear. The presence of inflammatory cells, blood or debris may affect the quality of the smear. Smear should not be taken during menstruation. If a patient has pre-existing infection, treatment before taking a cervical smear is advised. The broom type device gives a better yield of endocervical cells than the conventional Ayres' spatula but it is more expensive. If the cervical smear of a postmenopausal woman is reported to be unsatisfactory, consider giving oestrogen before repeating another smear. Cervical cells collected by the spatula should be properly transferred to the slide. Too thick a smear especially with blood or mucus makes interpretation very difficult. After being prepared, slides should be fixed immediately using either a spray fixative or dipping the slide into 95% alcohol. Liquid based preparations (Thin-prep) are much more expensive but could reduce the number of unsatisfactory smears by decreasing the problems mentioned above.5 The cytological examination request form should be filled in properly. Patient particulars should be checked carefully and the slide should be labelled in pencil. Important information which may influence the interpretation of the cervical smear, like the date of last menstrual period, menopausal status, contraceptive methods, pregnancy, and history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy should be written on the request form. Reporting a smear Different reporting systems are used for cervical screening. In order to ensure proper management of those women with abnormal cervical smears, it is important to understand the terminology of smear reports. A descriptive report using unequivocal terms, together with a recommendation regarding further management, is the type of report most acceptable to clinicians. The Bethesda System6 is now the most commonly used reporting system in Hong Kong and should be used uniformly. This classification was first introduced in 1989 by the National Cancer Institute and it was modified in 1992. In the Bethesda System, the term Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) is used to correlate with the histological diagnosis of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) grade I. In the presence of human papilloma virus changes, the smear will still be classified as LSIL even when no features of intraepithelial neoplasia are seen. High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HSIL) correlates with CIN grade II-III. Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance (ASCUS) means squamous cell abnormalities that cannot be accounted for by reactive changes but do not fulfill the criteria for a specific squamous lesion. According to the 1996 Hong Kong colposcopy data, 15% of the patients having persistent ASCUS have high-grade CIN or even invasive disease. Dealing with abnormal cervical smears An abnormal smear gives a cytological diagnosis. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia must then be diagnosed histologically. A woman with a cytological screening result showing a significant chance of having CIN II-III, should be referred to the colposcopy clinic for assessment. If a gross tumour is seen on speculum examination, urgent referral to a gynaecologist for a biopsy to diagnose cervical cancer should be advised. In case of ASCUS or inflammation, cervical smear should be repeated in 3 to 6 months to allow for regeneration of cervical epithelium. If no gross lesion is seen, please refer to Table 1 and Figure 1 for decision.

Before referring patients to the colposcopy clinic, the reason for referral should be explained to them in order to reduce their anxiety. Some patients might think that they are suffering from cervical cancer. The colposcopist will examine the transformation zone using a colposcope, an instrument incorporating a magnifying lens. Application of acetic acid and Lugol's iodine on to the cervix help to show up abnormal areas and biopsy will be taken from these abnormal sites for a histological diagnosis. The vagina would also be inspected during colposcopic examination. Histological confirmation of the colposcopic diagnosis is advised before embarking on treatment. Treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia If a low-grade lesion is confirmed by colposcopy and biopsy, the patient can be observed because 85% of them will return to normal in 2 years without treatment, although 15% of them may progress to higher grade lesions.7 However, for patients who are likely to default further assessment, treatment can be offered after adequate explanation. If a high-grade lesion (CIN II/III) is confirmed, treatment is suggested because a significant proportion will progress to invasive cancer if left untreated. The time of progression to invasive disease can vary from months to years. The risk of progression from CIN III to invasive disease is more than 12%.8 Call-recall system The effectiveness of a call-recall system in encouraging women to have a cervical smear has been confirmed by randomised controlled trial.2 Women belonging to the targeted population should be invited to have cervical smears. A recall system should be available to call patients with abnormal cervical smears and to remind women who are due for screening. Being informed of a normal cytology result should be reassuring and might make the screening programme more successful. Reading materials Please visit the website (http://www.hkcog.org.hk/collegeguidelines.htm) of The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists for a full text of the Guidelines on the Management of An Abnormal Cervical Smear. Key messages

K F Tam, MBBS, MRCOG, FHKAM(O&G)

Medical Officer, H Y S Ngan, MBBS, MD, FRCOG, FHKAM(O&G) Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr K F Tam, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tsan Yuk Hospital, Hospital Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|