|

August 2001, Volume 23, No. 8

|

Update Articles

|

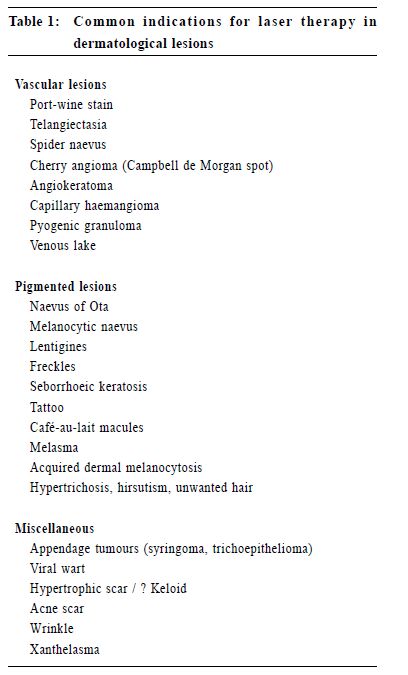

Laser therapy in dermatology: what have we learnt in the last decade?L Y Chong 莊禮賢 HK Pract 2001;23:323-330 Summary This article gives an overview on laser therapy in dermatology in the last decade. The basic principles, evolution and new developments of laser machines, their clinical applications in dermatological conditions, their efficacy, possible complications and potential hazards are discussed. The author has also discussed about the merits, limitations, uncertainties and controversies in this mode of treatment modality, and tried to give a balanced view on these matters. 摘要 本文回顧近十年來激光治療在皮膚病學上的應 用,探討激光治療的基本原理、演變、最新發展及其 在皮膚病方面的臨床應用、療效、併發症和潛在危 險。作者也討論激光治療的優點、缺點及不明確和有 爭議的問題,提出較全面平衡的意見。 Introduction In the past decade, laser therapy in dermatology has become very popular worldwide including Hong Kong. It is fashionable and drawing lots of attention from the medical profession, laymen and media. After all these years' experience and intensive work, it is perhaps an appropriate time for us to make a reappraisal and introspection of this treatment modality in dermatology. The word laser stands for Light Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Einstein in 1917 first postulated on the theory of Stimulated Emission, in which an atom in an excited state is forced to emit its energy in the presence of a proton of correct frequency, and this formed the fundamental concept of laser. Although Einstein's work is often cited as the birth of the laser, this could not be achieved without the contributions of other predecessors or successors. The important theory of quantum electrodynamics in 1950 by Feynman, Schwinger and Tomonaga (Nobel prize winners) also contributed greatly to the birth of laser machines.1 Despite these important concepts and theories in the early days, most laser machines that are used in medicine nowadays did not appear until 1960-70's. Skin as a readily and easily accessible organ, is obviously a good target for laser therapy. Goldman and colleagues published preliminary study on skin lesions in the early 70's , which signified the beginning of clinical applications of laser in dermatology. The concept of selective photothermolysis introduced by Anderson and Parrish in 1983 further established the foundation of modern laser therapy.2 In Hong Kong, the laser therapy on dermatological conditions was first started in the private sector around early 90's. It was not until 1993 that the public dermatological institute first installed a copper vapour machine in Social Hygiene Service and provided the service in the public sector.3 Despite the lag in starting this innovative treatment modality, laser therapy has boomed and developed rapidly in private and public sectors in the last decade. Dermatologists, plastic surgeons, family physicians and even beauticians from beauty salons have been enthusiastic and actively involved in applying this treatment modality. Principles of laser therapy There are three important properties of laser light that contribute to its therapeutic effects, namely, coherence, monochromaticity and high intensity.Coherence means the light waves are parallel and in phase. This allows the laser beam to be focused onto a small spot. Monochromaticity means the light waves have the same wavelength. This allows a selective absorption of a specific wavelength by the target. High intensity, as a result of the amplification of light energy, is sufficient to destroy the target. The most essential concept in modern laser therapy is the "selective photothermolysis", in which a specific wavelength of laser is used, aiming at selective destruction of the target and minimal damage to the surrounding normal tissues. In order to achieve the desired therapeutic effect, three ideal laser parameters must be fulfilled; namely, specific wavelength, suitable pulse-width and adequate energy fluence. Firstly, a specific wavelength, which is optimally absorbed by the target tissue, is needed, and this depends on the chromophore absorption curve of that target. Chromophores are substances used to absorb the laser light. In skin, they include haemoglobin in vascular lesions, melanin in pigmented lesions, and water in most tissues. While considering the selectivity of absorption, one must remember that in general, the longer the wavelength, the deeper the penetration of the light; and the longer the wavelength, the smaller the absorption coefficient. These properties would guide the operator to choose the suitable wavelength to treat specific skin lesions. In treating vascular lesion, yellow light is usually used; while in pigmented lesions, green light is usually used in epidermal lesions and red to infrared light (with longer wavelength) for dermal lesions. Secondly, one needs exposure duration that is less than the time necessary for cooling of the target structure, that is, less than the thermal relaxation time of the target. This can be achieved by using very short pulse of light or Q-switched device. Thermal relaxation time is defined as the time required for a target to cool from the temperature acquired immediately after laser irradiation to half that temperature. If the exposure duration to laser is greater than the time required for heat diffusion to the surrounding tissue of the target, the thermal damage will be extensive and non-specific. Thirdly, sufficient energy fluence is necessary to reach a destructive temperature in the target, and this depends on the laser power output and the spot size of the hand-piece of different laser machines. Clinical applications of laser therapy The common indications of laser therapy in dermatological lesions are summarised in Table 1. The responses to laser therapy, however, do vary between different dermatological conditions and different individuals. In general, those with good response include port-wine stain, telangiectasia, cherry angioma, angiokeratoma, capillary haemangioma, venous lake, naevus of Ota, lentigo simplex, freckle, seborrhoeic keratosis, etc. Those with satisfactory response include spider naevus, melanocytic naevus, café-au-lait, tattoo, appendage tumours, xanthelasma, etc. While those with unsatisfactory or unpredictable results include melasma, Becker's naevus, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, congenital lentiginosis, cavernous haemangioma, and keloid.

Different types of laser machines Basic components The basic elements of a laser machine consist of a power source, a gain medium and two optical resonators. The power source can be electrical, optical or chemical. The gain medium consists of the lasing material, for example, carbon dioxide, argon, copper vapour, etc. and the laser machines are named according to these lasing materials (Table 2). In operation, the power source stimulates the lasing medium, causing the excited atoms to emit the energy in the form of protons, which then resonate between the two reflective mirrors and stimulate more excited atoms to emit their energy. As a result, light is amplified in intensity and then finally released as laser.

Evolution of laser machines Laser machines, like other hi-tech innovations, develop from primitive models to sophisticated models as time goes by. In the early days, argon laser and carbon dioxide lasers with continuous wave emissions were used. These machines were bulky, unstable, expensive and carried considerable risks to the patients. With the rapid development of laser industry, more and more laser machines have been developed for the medical field. The improvements are not only confined to the lasing materials, but also include the delivery system, the cooling system and various new accessory devices. The evolution of continuous wave laser to quasi-continuous wave laser to pulsed or Q-switched laser, and the invention of cooling devices have greatly improved the efficacy and safety. The change of water-cooling system to air-cooling system has made the installation of laser system more feasible in ordinary clinics. The higher laser power output, larger spot size of the hand-piece, and the computerised automated scanner have facilitated the operating process and made it less operator dependent. New machines and devices Over the past decade, great advances and innovations in laser machines have been achieved. The followings are some of the currently available laser machines and devices that are worth mentioning:

The modern development of CO2 laser technology has greatly enhanced the safety of this type of machine. The old continuous wave CO2 laser was well known for its risk of thermal injury to dermis and adnexal structures, which can lead to permanent changes like scarring and pigmentation. The new generation pulsed CO2 lasers, complemented by various scanning devices (such as flash scanner or computerised pattern generator), have reduced the thermal damage and improved ablation uniformity. Carbon dioxide laser is mainly used in fine ablative procedures like resurfacing or removal of appendage tumours in dermatology. Er:YAG laser, like CO2 laser, is highly absorbed by water and is absorbed superficially in skin. It is therefore suitable for superficial skin resurfacing. Its merits include rapid healing, precision tissue sculpting and less post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. The latter is particularly useful in Orientals. The main indications are similar to CO2 laser. To improve the versatility of the laser machines and to increase their competitiveness in the market, there is a trend for the laser machine industry to launch combination models. Currently, various models are available in the market, which include the following combinations:

Diode laser technology is the hope of small, portable, economical and stable laser machines in the future. Currently, gallium aluminium arsenide diode laser (810nm) is available for hair removal. Skin cooling is used to minimise the epidermal damage in a variety of laser dermatological procedures, including port-wine stain removal, leg vein treatment and photoepilation. Spray and contact cooling are two popular methods. Based on this rationale, different systems have been developed by different laser companies, for example, chilled-tip delivery system used in the treatment of vascular diseases. This reduces the epidermal damage, pain during treatment and downtime. In combining skin cooling and new non-ablative laser machine (such as 1.32mm Nd:YAG), one can achieve the purpose of non-ablative resurfacing. Complications and hazards Just like other aesthetic surgery, laser therapy may have complications and hazards (Table 3). The early continuous wave and quasi-continuous wave lasers are extremely operator dependent and can potentially result in significant risks including scarring.4 The pulsed and Q-switched systems of modern laser adhere most closely to the principle of selective photothermolysis, and thus result in more selective destruction of the target and minimising the risk of scarring through unwanted thermal diffusion. Despite these improvements, laser therapy may still result in significant scarring especially in procedure like resurfacing, when the ablation needs to go down to the dermis, in order to stimulate a healing response resulting in deposition of increased amount of new collagen in skin. Other risk factors of scarring include the use of continuous wave laser in children, keloid tendency, and treatment at bony area like the jaws, shoulders and the presternal area.

Most medical lasers are Class 4 devices with high output. They are capable of causing eye injuries, skin injuries and fire hazard, and therefore must be used with extreme care. The occupational health hazard with surgical smoke released during laser therapy has also raised concern. The Health Hazard Alert from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) warned on the dangers of the smoke plume, a byproduct of the thermal destruction of tissue released during laser therapy.5 The smoke plume may contain toxic gases, dead and live cellular material and viruses. Smoke evacuator system with viral and carbon filters should therefore be used by the operators. Protective high efficiency laser mask that filters out particles greater than 0.3 micron is also important. Limitations and uncertainties Despite the wide clinical applications and enthusiasms in laser therapy, there are still lots of limitations and uncertainties about this treatment modality.

What are new in the applications? Current trend After years of treatments on cutaneous vascular and pigmented diseases, there is a general trend to use laser as a cosmetopeutic tool. More and more applications are now on cosmetic purposes, such as photoepilation, hair transplantation, tattoo removal, resurfacing for scar or wrinkle and facial rejuvenation. One of the hot topics is hair removal, in conditions like hypertrichosis, hirsutism or unwanted hair for aesthetic reasons (hair at axilla, bikini line and face). Various systems, such as ruby laser, Nd:YAG laser, diode laser and intense pulsed light have been used for this purpose. These photoepilation devices target follicular melanin as chromophore, resulting in thermal destruction of the hair follicle and shaft. To the contrary, laser technology is also used in hair restoration. The advent of carbon dioxide or Er:YAG laser-assisted hair transplantation in recent years provides a new recipient area technique for hair restoration surgery. It has the advantages of less bleeding, less time consuming, less graft compression, and providing precise preparation of the reception area for implantation. Other new applications These include the dermablation of cutaneous amyloidosis with frequency-doubled Nd:YAG, carbon dioxide10 and pulsed-dye laser; laser phototherapy with 308nm excimer machine in psoriasis,11 etc. Their efficacy needs further study. Controversies in laser therapy Laser, being a relatively new treatment modality, inevitably will have many controversial and debatable viewpoints. The following are some issues for discussion: Is this really an indication for laser therapy? In considering laser therapy, dermatologists have no doubt that conditions like port-wine stain or naevus of Ota should be regarded as medical indications than simply for cosmetic purpose. However, the boundaries between medical, psychological or aesthetic indications become blurred for lots of other cutaneous conditions, such as telangiectasia, melanocytic naevus, wrinkle or unwanted hair. One may therefore argue if it is worthwhile to use this invasive procedure to treat these benign conditions. Nevertheless, as time advances, more and more cutaneous conditions are attended to with laser therapy despite these controversies. Long lists of indications are included in laser literatures and brochures of the laser companies. These however must be interpreted with great cautions, as some of these indications are only based on small-scale uncontrolled study, case report or even anecdotal personal impression. Even for formal well-designed study, assessment of the end-results of laser aesthetic surgery is often bound to have biases among the assessors. Before one proceeds to use the laser machine, one has to judge whether it is really useful and indicated, or simply a marketing tool. What is the optimal timing for laser therapy? This aspect is of special concern in children. The opinions on the optimal age for laser therapy in paediatric patients are still diverse among the medical profession. It is still a common concept among doctors that very small children should not be treated until they are older, although some enthusiastic operators believe that there is potential psychological benefit in starting the treatment at as early an age as possible, and treatment is safe and effective even for infants.12 One certainly has to consider the risks of anaesthesia and consequences of noncooperation among small children. High scarring risk with the old continuous wave lasers (like argon or copper vapour) in children makes this group of machines almost obsolete. Condition like strawberry haemangioma, which has a tendency to resolve spontaneously, should not be treated with this aggressive approach unless it occurs near the vital organs or leads to complications. Should the public health resources be allocated to aesthetic laser surgery? Due to the high costs of laser therapy, financial implication is great in this treatment modality, which is basically confined to more affluent areas at present. Patients' affordability, cost and maintenance of the laser machines, fee of the operators are the factors to be considered before one commences a laser clinic. In general, the set up of a laser centre with different machines used by multiple operators would be much more cost-effective than solo practice. An even more important issue, however, lies in the concern of budget holder for public resource allocation: how much of the public resource should be put on aesthetic laser therapy? Although laser therapy is fashionable, a symbol of hi-tech development, easier for application of new research funds and publications, the fundamental service needs and basic research in dermatology should not be overlooked or compromised. Should the use of medical laser machines be legally regulated?13 In recent years, there is a growth in beauty parlours in Hong Kong offering cosmetic laser treatments to their customers. Some of these beauty parlours use Class 3b laser machines and recently one even uses Class 4 machine for photoepilation. This raises the concern about the use of these potentially hazardous devices by inadequately trained non-medical personnel to treat medical conditions. Class 3b and Class 4 laser machines are high power devices that pose not only risks to patients, but also occupational health hazards. Unfortunately, there is no special regulation for importing and placing of laser machine in Hong Kong. Legal opinion here also stated that Medical Regulation Ordinance could not restrict the use of laser to medical doctors, especially in the grey area of defining whether it is a medical or a cosmetic treatment. Although there is great difficulty in legislating against the improper use of medical devices due to the interests of different stakeholders, it is an international trend to safeguard the consumers' safety, and Hong Kong should be harmonised with the international standard. According to health authority, regulation of medical equipment nowadays is only practical when it is riskbased. However, to safeguard the public health, this should be based on prospective views rather than hindsight. Among the profession, a consensus on appropriate standards is also imminently needed for a properly supervised training programme for laser therapy. Who should be the right person to perform laser therapy? Expertise and experience are important in laser therapy. Although legally every registered medical practitioner can perform laser treatment, the operators have to consider whether they are able to defend themselves with their record of experience and training if medico-legal dispute arises. In some countries, laser therapy is also widely performed by family physicians or even specialised nurses, but proper training and supervision are essential. For dermatological patients, studies had shown that there was a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders.14 Their symptoms may be out of proportion to the skin lesions, or the skin disease and psychological disturbance may be linked. Some patients who are over-enthusiastic with laser therapy do have a certain type of personality trait that includes anxiety, tension, demanding character or even dysmorphophobia. These patients may at times be over-demanding and have unrealistic expectations from the treatment. As a result, medico-legal dispute is likely to occur. Suitable recruitment of patients, preoperative psychological preparation, and full explanation about the limitations and possible complications beforehand are therefore essential. Prospects for the future Hopefully, with the advance of modern laser technology, an "ideal" laser machine will be available in the near future. An ideal laser machine should be one which is efficacious, safe, free from side-effects, having a fast recovery phase, versatile with a wide range of applications in different ethnic groups, handy and portable, easy to operate, stable and reliable, affordable and within a reasonable price range. Diode laser is probably one of the potential candidates to fulfill these criteria. Although many cutaneous conditions which are previously untreatable or unsatisfactorily treated with old laser machines are now amendable to treatment with the newer versions, further improvement and search of new applications are still needed for lots of other conditions. Apart from pigmented or vascular conditions, another challenge for laser treatments in the future is to develop ways of treating non-pigmented and non-vascular skin "targets". It is also hoped that more experience can be gained and more evidence-based researches can be conducted to look for new applications and clarify the uncertainties of laser therapy that exist, such as optimal treatment interval, treatment parameters and endpoints, as well as prognostic factors. As usual, there is often discrepancy between theoretic consideration and actual treatment outcome, and these should be carefully studied through actual practice. Finally, although development in this field is desirable, the medical profession should not sacrifice basic research in dermatology and put all weight at one side of the balance, especially in the health resource allocation. Conclusion Laser therapy no doubt has revolutionised and widened the dimension of treatments in dermatological conditions. This innovative technique has signified the integration between hi-tech and clinical practice in medicine. As time goes by, there are more and more new laser machines available. To many patients, laser therapy is a miracle as it offers new hopes to them. However, as discussed above, there still exists many limitations, uncertainties and controversies. At times, it can be a nightmare to patients, especially for those who have irreversible complications. Hopefully, the medical profession can treasure this precious tool and does not misuse or overuse it. Key messages

L Y Chong, FHKAM(Med), FRCP(Lond, Edin, Glasg), FHKCP

Consultant Dermatologist, Social Hygiene Service, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Dr L Y Chong, Yaumatei Dermatology Clinic, 12/F, Yaumatei Specialist Clinic (New Ext), 143 Battery Street, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

|