|

August 2001, Volume 23, No. 8

|

Update Articles

|

Management of cancer painR P L Chan 陳佩蘭, T W Lee 李振垣 HK Pract 2001;23:331-336 Summary Pain is common in advanced cancer patients. It is often undertreated, and this may be due to factors related to the doctors, to the patients and to the health care system. Optimal management involves careful assessment and choosing the appropriate therapeutic regime. Although opioid analgesic is the mainstay of treatment, symptomatic treatment of its side effects, addition of adjuvant drugs and integration with other therapies are essential for successful holistic management. 摘要 晚期癌症病人常有疼痛。由於醫生、病人及醫療 制度的因素,這類病人常未能得到充分治療。最佳的 處理方法是要謹慎評估病情,再選擇適當療法。類鴉 片止痛劑是主要的方法,但它的副作用要適當處理; 並結合其他輔助藥物和療法,才能讓晚期癌症病人得 到全面妥善的治療。 Introduction Pain is a common symptom in at least 30% of patients undergoing treatment for metastatic disease and in over 70% of patients with advanced cancer.1-3 Quality of life is compromised by poorly controlled symptoms which will have serious impact on both the patient and the family. Adequate pain relief can be achieved in about 90% of patients with appropriate drug therapies.4 However, cancer pain is often undertreated. In a multicenter study,5 36% of patients with metastatic disease had pain severe enough to compromise their daily function. Women older than 70 years of age were more likely to have inadequate analgesia. Barriers to adequate pain management The reasons for undertreatment of cancer pain include factors related to health care professionals, to patients and to the health care system. Many health care professionals are not trained in pain management. Poor assessment of pain, fear of drug addiction, concern about side effects of analgesics and about development of tolerance to analgesics may cause inadequate pain treatment.6-8 Secondly, "good" patients are reluctant to report pain. They are concerned about disturbing the health care staff or distracting physicians from treatment of the underlying disease. Other patients have fear of addiction or side effects. These concerns occur more in patients with less education, lower incomes and higher levels of pain.9 Thirdly, cost could be an issue in cancer pain management. It is of major concern especially in small hospitals where providing acute health care service is a priority.10 Components of cancer pain management Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.11 It is not merely a sensation; it also has a psychological component and may involve tissue damage. Optimal cancer pain management involves careful assessment of pain characteristics and choosing the most appropriate therapeutic regime with or without integration with other therapies. A holistic approach is important and multidisciplinary care is necessary.

Cancer pain should be assessed by history, physical examination and investigations. The expression of cancer pain changes constantly and new causes emerge rapidly,thus regular reassessment is essential. Some of the common causes of cancer pain are listed as follows:

In the history, pain characteristics have to be sought and the main components include intensity of pain, character, location, radiation, timing, aggravating and relieving factors. Intensity of pain can be assessed by the use of visual (VAS) or verbal analog scale (VRS). The rating scale ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain one can imagine. In VAS, the rating scale is displayed on a ruler for the patient to choose a point on the scale, while in VRS, the patient chooses a number from 0 to 10 to represent his pain intensity. However, since pain is a multidimensional experience, physicians cannot rely on pain score alone to evaluate treatment efficacy. Other factors have to be considered, such as what level of pain is considered tolerable; how pain interferes with daily function. One method for multidimensional evaluation of cancer pain is the use of Brief Pain Inventory, in which patients rate their pain (0 to 10) together with self-assessment of pain interference with everyday functions (seven areas of psychosocial and physical activities). Doctors and nurses tend to underestimate pain intensity and in turn lead to undertreatment. The character of pain may help to establish the cause of cancer pain. Nociceptive pain originating from somatic structures is usually well localised and characterised as sharp, aching, throbbing or pressure like. Visceral pain is typically more diffuse. In obstruction of a hollow viscus, it is gnawing or cramping or colicky in nature. When organ capsules or mesenteric structures are involved, the pain tends to be aching, sharp or throbbing. Neuropathic pain occurs after injury to the nervous system. The pain may be continuous or episodic lancinating. It may be described as burning or sharp cutting although the painful area may be paradoxically numb. The location and radiation of pain are important in both diagnosing and treating the patient. Pain may be due to injury at the site or referred pain. Pain at the lumbar spine with radiation to both legs suggests nerve injury at the spine level. Localised pain may be managed by localised therapy, for example, radiotherapy or nerve block with or without systemic analgesia. Generalised pain is usually managed with systemic analgesic agents. The timing of pain may be associated with activity (incident pain) or end of a dosing period (breakthrough pain). Associated aggravating and relieving factors can help to find out the cause of pain. Headache which is worse on straining may indicate brain metastases. The effect of current medication on pain treatment has to be assessed. The degree of limitations to patients' daily activities can reflect the severity of pain. Sleep disturbance, loss of appetite, poor social interaction with significant others suggest severe pain. Lastly, it is important to understand what the pain means to the patient. Hidden fear, such as concern about more investigations and treatment, may lead to underreporting of pain. Physical examination should include examination of the painful areas and a full neurological examination. Radiological examination including plain x-ray, bone scan, computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be needed to find out the cause of pain. World Health Organisation (WHO)12 has established guidelines for cancer pain relief. According to the WHO analgesic ladder, pain management passes through various steps until pain relief is achieved. The first step is to use a non-opioid analgesic, such as paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). If pain relief is not achieved, then the next step suggests the use of weak opioids (e.g. codeine) and finally progresses to the use of strong opioids (e.g. morphine). Other drugs may be added to treat side effects or used as adjuvant analgesics. These include tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, anti-emetics or sedatives. Combination therapy, such as paracetamol and opioid, is commonly employed. The basic principle with the use of analgesic ladder is "by the ladder, by mouth, by the clock and for the individual." The largest study reporting the experience with the WHO ladder in cancer patient was performed by Zech et al.13 In his study, efficacy of pain relief was "good" in 76% of patients. However, there were doubts about starting at step one for every patient. According to Zech et al, 25% of patients at this stage had moderate to severe pain. Going through the steps of the 'ladder' strictly may lead to delay in establishing adequate analgesia. A more flexible approach, to treat according to the severity, is recommended by the Agency for Health Care P o l i cy and Research (AHCPR) Cancer Pa i n Guidelines14 in 1994. With a pain score of 1 to 4 (mild pain), paracetamol or NSAIDs are used. If the pain score is 5 to 6 (moderate pain), the treatment should start at step 2, and a weak opioid is used. For severe pain (pain score of more than 7), one should start at step 3 with strong opioids.

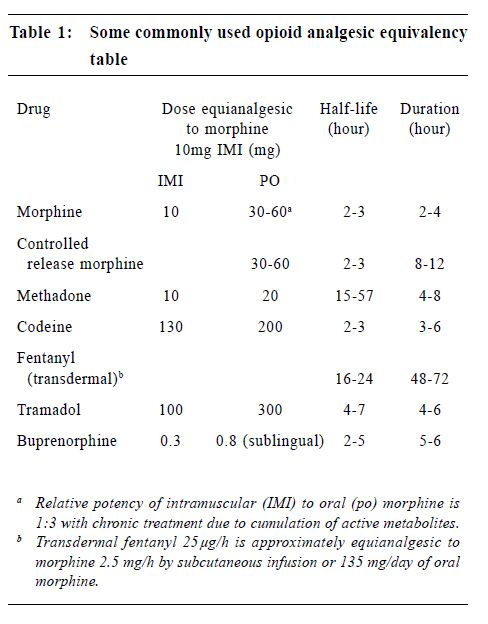

Oral opioids are the primary treatment for cancer pain, though they are more effective in treating nociceptive pain syndromes than neuropathic pain syndromes.15 Therapy is often initiated before the aetiology of pain is established. For opioid-naïve patients, it is recommended to titrate with an immediate release preparation. An example is to give regular oral morphine at a starting dose of 2.5-5 mg 4 hourly during the day and 5-10 mg at night. If adequate pain relief is not achieved, the dosage can be increased by 30-50% every one to two days. The aim is to achieve a balance between adequate analgesia and minimal side effects. There is no "maximal" dose. Oral morphine undergoes extensive first pass metabolism in the liver. Only a small fraction (approximately one third for chronic dosing) goes into the blood stream and is effective. Hence, care should be exercised in patients with liver failure. These patients should be started on a lower dosage and be titrated more slowly. In patients with renal failure, active metabolites will accumulate and result in toxicity. Opioid needs to be started at a lower dosage or be administered at longer intervals, such as 6 or 8 hourly instead of 4 hourly. While opioid therapy is the mainstay of treatment, other adjuvant therapy can be added. Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) is useful for neuropathic pain ("burning pain" as described by patients) and it potentiates the analgesic action of opioids. Sleep pattern is improved. The dosage used in pain management is generally lower than for treatment of depression. For example, amitryptyline may be started at 10-25 mg nocte and increased slowly every 2-3 days. Dosage over 100 mg nocte does not seem to offer additional advantage. Side effects include excessive sedation, particularly in the frail and old, dry mouth and cardiac arrhythmia. Dothiepin and nortriptyline may have less sedating and anticholinergic side effects. Anticonvulsants are useful in treating neuropathic pain characterised by lancinating or paroxysmal dysaesthesias. Carbamazepine is widely used in the past but it is associated with side effects such as nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, rash and blood dyscrasia. Valproate is an effective alternative. Baclofen, which relieves muscle spasm, is sometimes used for paroxysmal or lancinating neuropathic pain. NSAIDs are indicated for mild to moderate pain, especially in patients with somatic pain from inflammation or bone metastases. They produce dose-dependent analgesic effects and have a ceiling dose for analgesia. When combined with an opioid in treating more severe pain, they have opioid sparing effect. Side effects are due to cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-1 inhibition and include gastrointestinal and renal toxicity, platelet dysfunction. Coadministration of steroid and NSAID should be avoided as it increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. The use of COX-2 selective inhibitors, e.g. rofecoxib, has significantly decreased these side effects. Corticosteroid is effective in treating metastatic bone pain,16 hepatic capsular distension, symptomatic lymphoedema, nerve plexus or peripheral nerve compression, superior vena cava syndrome, spinal cord compression and raised intracranial pressure. In these painful syndromes, a dose of oral dexamethasone 4-8 mg is given initially and is tapered to a lower dose (2-4 mg daily) when there is a response. In case of suspected spinal cord compression while waiting for radiotherapy or surgery, an intravenous bolus of dexamethasone (16-32 mg) can be given. Intravenous dose of 100 mg dexamethasone is indicated in patients with severe headache secondary to increased intracranial pressure. In patients with malignant intestinal obstruction, anticholinergic drugs, such as buscopan, are useful in reducing pain and vomiting. When pain is reduced, the physician should continue to look for the cause of pain and treat accordingly. For example, antibiotics should be prescribed for infection, local anaesthetics application for pressure sore, immobilisation or surgical treatment for pathological fractures, etc. Analgesic therapies have to be consolidated. Short acting opioids could be converted to longer acting preparations to improve compliance. An example is MS Contin (MST). The total daily dose of morphine can be converted to MST directly by dividing the total daily opioid consumption in equal doses of MST to be given 12 hourly or 8 hourly. Another example is transdermal fentanyl patch. It eliminates the need for oral opioids and has a lower incidence of constipation. Each transdermal fentanyl patch usually provides three days of analgesia. However, it needs to be changed every two days when the patient has fever which enhances the release of fentanyl and shortens the period of use. Dosage can be converted according to Table 1. In addition, short acting opioid should be prescribed for breakthrough pain on an as-needed basis. The dosage is usually 10-15% of the regular daily dose. Another consideration is to manage the opioid side effects. For example, laxatives should be prescribed at the same time to prevent constipation. Stimulants and stool softener are preferred to bulking agents and osmotic laxatives. Antiemetic should be available to prevent nausea and vomiting. If a patient experiences dose limiting side effects with one opioid, he may benefit from another opioid. There is wide individual variation in the therapeutic window and side effects of different opioids. The process of changing opioid requires the knowledge of equianalgesic opioid dosing (Table 1). In general, the starting dose of the new opioid needs to be reduced by 25-50% to account for incomplete crosstolerance between different opioids. A change of route of administration to intraspinal or transdermal route may also help to decrease side effects.

Regular reassessment is the key to successful management. Adjustment of dosage depends on patients' response to treatment. For example, if adequate analgesia is not achieved during the dosing period, an increase in dosage is probably of benefit. However if pain is experienced at the end of the dosing period, short acting morphine should be prescribed for breakthrough pain and the total daily dose can be increased a few days later after stabilisation. Pain therapy has to be individualised. If the patient cannot tolerate oral medication, other routes of administration have to be considered. Morphine given by subcutaneous injections or infusion via a small syringe driver can be useful. The difficult patients should be referred to specialists for management. Apart from opioid treatment, other therapies are often integrated into the pain programme.

For advanced tumour when palliative care is the aim, the doctor should strike a balance between the benefits of anticancer therapy and its potential side effects. Radiotherapy is useful in pain control for bone metastases (particularly carcinoma arising from the lung, breast and prostate). The overall responses are usually 70 to 80%, independent of tumour histology.17 Radiotherapy is also helpful for pain relief in epidural spinal cord compression,18 control of tumour ulceration, superior vena cava obstruction, bronchial obstruction and the management of cerebral metastases. The peak analgesic effect occurs about 2 to 4 weeks later and other treatment is required during this period. For suitable patients, intravenous radioactive Strontium is useful for treatment of bone metastases. Bisphosphonates are sometimes also useful for treating the pain of bone metastases.19 They are indicated when other conventional analgesics and adjuvants fail to control bone pain and at the same time they treat hypercalcaemia. Psychological support is important and should be considered early in the course of illness. Cognitive and behavioural techniques can help these patients.20 For instance, providing information about pain and its management help the patients to think differently about pain and is a form of cognitive technique. Behavioural techniques, such as hypnosis, distraction or relaxation can be learned by the patient to cope with pain. Participation in self-help group, family support and pastoral counselling may also help cancer patients to deal with the illness and pain experience. Nerve blocks have a role in some cancer patients. These are indicated when conventional analgesics fail. Autonomic nerve block, such as celiac plexus block, is useful in neoplastic infiltration of the upper abdominal viscera,21 including the pancreas, upper retroperitoneum, liver, gallbladder and proximal small bowel. Somatic nerve block, such as intercostal nerve block, helps in rib secondaries. Spinal or epidural opioids are sometimes administered to patients who have unmanageable side effects of opioids such as somnolence. Generally, one tenth of the intravenous opioid dose is needed epidurally and one hundredth is needed if given intrathecally. The procedure involves the insertion of an intra-spinal catheter that is connected to a subcutaneous injection port of reservoir. Physical therapies, such as cutaneous stimulation (massage, heat and cold compress), physiotherapy, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation and acupuncture may decrease the need for analgesics. In patients with delayed and inadequate pain control, pain may be refractory due to activation of n-methyld- aspartate receptors in the spinal cord. These patients may benefit from ketamine infusion. The very difficult patients who cannot be managed by oral analgesics alone should be referred to specialised centres where palliative care physicians, anaesthesiologists and other allied health professionals can provide these modalities of treatment. Conclusion Pain in cancer patients is often undertreated. An understanding of the barriers to pain treatment, mechanisms of cancer pain, factors that affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of analgesic agents help to provide proper cancer pain management. A holistic approach and multimodal type of pain management help to improve the quality of life in these patients. Key messages

R P L Chan, MBBS(HK), FHKCA, FHKAM(Anaesthesiology)

Associate Consultant, T W Lee, MBBS(HK), FANZCA, FHKCA, FHKAM(Anaesthesiology) Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia & Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr T W Lee, Department of Anaesthesia & Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, N.T., Hong Kong.

References

|

|