February 2001, Vol 23, No. 2 |

Update Articles

|

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus – a family physician’s perspectiveS K Kwok, P C P Ho, G K O Chau HK Pract 2001;23:57-62 Summary Herpes zoster is commonly encountered by family physicians. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is of special interest because it is a potentially blinding disease if left untreated. It is amongst the commonest cause of corneal scarring and secondary uveitis in ophthalmic practice. The role of primary care physicians is important because antiviral therapy is most effective with treatment begun within 72 hours of onset of rash. The purpose of this article is to address the diagnostic dilemma faced by family physicians and to discuss the various aspects of treatment. Introduction The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) VZV is responsible for chickenpox (varicella) and herpes zoster (HZ). VZV is one of eight herpesviruses that infect humans and is characterised by rapid growth and spread, destruction of infected cells and the ability to establish latent infection primarily in ganglionic tissue (neurotropism).1 The great majority of herpes zoster cases result from reactivation of latent virus. The most important risk factor for developing HZ is related to the status of cell-mediated immunity (CMI) to VZV. Thus, the incidence of HZ increases with age, with immunosuppression (such as due to human immunodeficiency virus infection), or immunosuppressive therapy.2 The trigeminal ganglion Most dorsal root and cranial nerve ganglia from immune individuals contain detectable latent VZV (65% to 90% of trigeminal, 50% to 80% of thoracic, 70% of geniculate ganglia).3 Reactivation of the virus that resides in the trigeminal ganglion with disease that involves the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve is referred to as herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO). Single dermatome: multiple site involvement In contrast to dorsal root ganglion that supplies only the dermatomes, the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve also supplies visceral structures. The ophthalmic nerve branches into the frontal, nasociliary, supraorbital, and supratrochlear branches. These branches innervate the facial region, the palate and the eyeball. The nasociliary nerve Involvement of the nasociliary nerve often signifies intraocular involvement because it has intraocular branches. Pathogenesis of HZO As a whole, 50% of patients with HZO develop ocular complications.4 There are diverse pathogenic mechanisms that include direct invasion, vasculitis, neuritis, and host immunologic reactions. The inflammatory reaction can occur in any portion of the eye or periocular tissue.5 Common ocular complications of HZO include:4

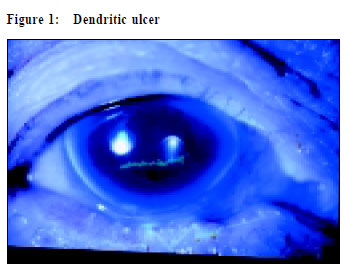

HZO in immunosuppressed patients Patients with cancer, leukaemia, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome are all at increased risk of HZ because of immunodeficiency. Severe cutaneous lesions and keratouveitis characterise HIV patients with HZO. VZV is known to cause acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome and progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) syndrome especially in immunosuppressed individuals. Retinitis develops either from reactivation of latent VZV or during primary infection. Retinal detachment arising from retinitis is devastating. Medical and surgical management is only partially effective in salvaging vision. Other features of HZO in HIV patients include lower age at onset, multiple dermatomal involvement, ocular disease sine herpete, chronic infectious dendrites, and serious neurologic complications.6 Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) Incidence of PHN increases markedly with age and is an important cause of chronic morbidity. Unfortunately, the pathophysiology of this debilitating condition is not completely understood. It is unrelated to the degree of inflammation of the peripheral nerve and the occurrence of ocular complications.7 Both the afferent pathways and the CNS are thought to play a key role in PHN because sectioning of the peripheral nerve does not completely relieve the pain. The normal descending inhibitory inputs from the CNS are thought to have been damaged by HZV and results in hyperexcitable state of the ascending fibers.8 A family physician’s perspective Early manifestations Patient with HZO typically presents with malaise, headache, fever and nausea, which are followed by burning itching and tingling sensation in the involved area. Later there is hot, flushed hyperaesthesia with oedema in the forehead where the vesicles erupt. Diagnostic pitfalls Before the vesicular phase, HZO may be mistaken as preseptal cellulitis or cellulitis on the forehead. Some patients have the neuralgia without ever developing a cutaneous eruption (zoster sine herpete). Likewise, a patient may develop intraocular complications in the absence of the vesicular phase. Clinical clues to diagnose intraocular involvement It is essential to ask if the patient noticed any change of vision after the onset of rash. Visual acuity testing is mandatory as visual loss always signifies a severe intraocular process. The corneal clarity of the patient has to be noted. A hazy cornea can be the result of keratitis or glaucoma that necessitates immediate treatment. Examination of a fluorescein stained cornea with blue light from a direct ophthalmoscope is a convenient way to look for corneal ulcer (Figure 1).

Peri-ciliary flush indicates presence of iritis. Testing of corneal sensation and extraocular movement are simple but important office procedures to look for cranial nerve palsies. Oedema of the forehead with swollen eyelid can lead to tear film disorder that results in mild conjunctival hyperaemia. This condition is benign and will resolve after the periorbital oedema subsides without causing chronic visual loss. The Hutchinson’s sign Cutaneous vesicles at the side of the tip of the nose (Hutchison’s sign) indicate nasociliary involvement and a greater likelihood that the eye will be affected (Figures 2&3). However, ocular involvement can occur even if the side of the tip of the nose is not affected. A negative Hutchison’s sign does not obviate the need to perform a basic eye examination.9

Treatment General treatment Hospitalisation for rehydration, pain control and intravenous drug administration is necessary if the general condition is compromised. Antiviral treatment The mainstay of treatment is anti-viral medications that are given topically, orally or via parental route. Antivirals must be given within 72 hours of onset of rash for maximum effect. Acyclovir Acyclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir are commonly used by family physicians to treat herpes zoster. These drugs are dependent on viral thymidine kinase phosphorylation and are targeted at viral polymerase. A large, prospective, doubleblind controlled study confirmed that late ocular inflammatory complications occurred in approximately 29% of patients treated with acyclovir versus 50% to 71% of untreated patients.10 Acyclovir use in HZO leads to a reduced incidence of pseudodendritic keratopathy, episcleritis and iritis. There is little if any effect on corneal hypaesthesia, neurotrophic keratitis, or postherpetic neuralgia. The usual duration of treatment for HZO is 10 days. Acyclovir has the added advantage of its availability in topicals forms (5% ointment). Several studies have reported that 5% acyclovir ointment combining with topical steroids is highly effective in resolving HZO epithelial keratitis and in preventing recurrent disease, in comparing with control patients receiving topical steroids alone.11 Valacyclovir Valacyclovir is the prodrug of acyclovir. By using a stereospecific transporter to facilitate gastrointestinal absorption, the plasma concentration of acyclovir is enhanced. The result of a multi-centre, randomised, double-masked study in France is published recently. The efficacy of valacyclovir in treating HZO is found to be comparable with acyclovir.12 Its advantages over acyclovir are simpler dosage schedule (three times daily versus five times daily) and shorter course (7 days versus 10 days). However, valacyclovir is much more expensive than generic acyclovir. Famciclovir Famciclovir is the oral form of penciclovir. The intracellular half-life of famciclovir in herpes virus infected cell in vitro is 10-20 hours versus approximately one hour for acyclovir. In an unpublished randomised, double masked clinical trial, 454 HZO patients were treated for 7 days with either famciclovir 500mg three times daily or acyclovir 800mg five times daily. Eighteen percent of acyclovir -treated patients developed keratitis, compared with 13% of famciclovir patients. Decrease in visual acuity was found in 6.3% of acyclovir -treated patients and in 2.6% of famciclovir patients. Approximately 25% of patients in both groups experienced uveitis.13 Foscarnet The majority of acyclovir resistant mutants of VZV have been found in AIDS patients, relating to diminished viralencoded thymidine kinase function which acyclovir acts on. Foscarnet inhibits DNA replication by directly inhibiting the viral DNA polymerase and does not require phosphorylation by the VZV thymidine kinase. Therefore, viruses with mutations in the thymidine kinase gene are still susceptible to inhibition by foscarnet. However, foscarnet can be given only parentally and its use is usually limited to physicians specialised in treating infectious diseases.14 Pain control of HZO Acyclovir, famciclovir and valacyclovir will reduce the acute pain if given within 72 hours after the appearance of rash. Administration of corticosteroids in combination with an antiviral agent may be considered in patients with severe pain and without contraindications to steroidal treatment. However, the effect of antiviral agents and steroids on the incidence, severity and duration of chronic PHN is not as consistent as their beneficial effects on acute PHN.7,15-17 As mentioned earlier, the mechanism of chronic PHN may be related to hyper-excitability of afferent neurons due to decreased inhibitory signal from the central nervous system. Aggressive pain control at the onset of HZO, especially in elderly patients, may reduce the magnitude of the initiation phase of nociceptor-evoked central hyperexcitability. The possible mechanism is that early pain suppression may reduce the production of factors that maintain abnormal central processing. Based on this concept of pain modulation, adrenergically active antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or desipramine are employed to treat PHN. There are studies indicating that routine use of tricyclic antidepressants in all patients older than 60 may reduce the incidence of chronic PHN.18,19 In summary, current therapeutic strategies for acute HZO include an antiviral and good pain control. Use of tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline in all patients older than 60 may decrease the chance of developing post-herpetic neuralgia. In the presence of post-herpetic neuralgia, one could combine topical application of a local anaesthetic with a tricyclic antidepressant. DMDA receptor antagonists such as dextrorphan, dextromethorphan are also effective in suppressing nociceptor-evoked central hyperexcitability.20 Prevention of HZO Pilot studies have been done in the Veterans Administration hospital system with live attenuated vaccine in patients 60 or older to determine if varicella vaccine will decrease the incidence of HZ, and to evaluate its effect on the cellular immune response to VZV. The expected result is that it may protect against reactivation of HZ.21,22 We are looking forward to the result of these studies to determine whether varicella vaccine should be given to the elderly as a prophylactic treatment against the development of herpes zoster. Conclusion HZO is a treatable cause of blindness. A basic eye examination by a family physician should be performed in all patients with HZO to exclude intraocular involvement. An immunosuppressed patient is more likely to have vision threatening complications and should always be referred to an ophthalmologist for detailed assessment. Key messages Antivirals in herpes zoster ophthalmicus:

S K Kwok, FHKAM(Ophthalmology) P C P Ho, FHKAM(Ophthalmology) G K O Chau, FHKAM(Ophthalmology) Correspondence to : Dr S K Kwok,Suite 7A, 28 Yee Woo Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. References

|

|