|

June 2001, Volume 23, No. 6

|

Update Articles

|

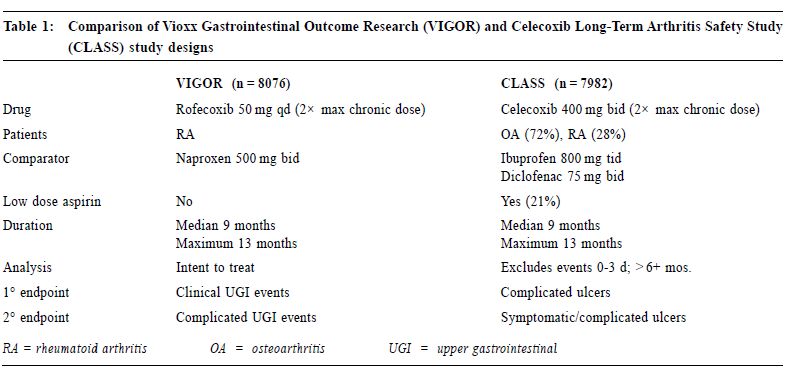

New approach of arthritis management: a physician-patient perspectiveS H K Huang 黃憲綱 HK Pract 2001;23:238-245 Summary Traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit COX-1 and COX-2. By inhibiting COX-2, these drugs have analgesic, anti-inflammatory effects. By inhibiting COX-1, they can cause upper gastrointestinal (UGI) symptoms, lesions, complications; renal dysfunction, reduction of platelet aggregation and other side effects. COX-2 specific inhibitors on the other hand inhibit only COX-2. Therefore, they should be analgesic, anti-inflammatory without the UGI, platelet side effects associated with traditional NSAIDs. Clinical trials including large scale, prospective, controlled studies using clinically significant UGI complications such as perforation, gastric outlet obstruction, or bleeding (POB) and perforation, ulcers (symptomatic or complicated), or bleeding (PUB) as end points have proven that celecoxib and rofecoxib have analgesic, anti-inflammatory effects comparable with traditional NSAIDs, without the usual UGI side effects associated with the traditional NSAIDs. This improvement in UGI safety should increase physician's confidence in prescribing COX-2 specific inhibitors and patient compliance in taking these drugs. While there are still unresolved questions regarding the COX-2 specific inhibitors, they should be considered the NSAID of choice for patients with musculoskeletal pain, especially for patients at risk of developing NSAID induced UGI side effects. 摘要 傳統的非類固醇消炎藥同時抑制環氧合 J1 (COX-1)及環氧合 J2(COX-2),藉抑制COX-2,藥物 能發揮止痛、消炎作用。但同時亦會抑制COX-1,因 而引致腸胃不適等併發症、腎功能失調、減低血小板凝 聚力及其他副作用。專門抑制COX-2的藥物則只有止 痛、消炎作用而不會引起其他副作用。臨床研究顯示專 門抑制COX-2的藥物和傳統的藥物比較,止痛、消炎 功用相若,但沒有傳統藥物常見的腸胃潰瘍、出血、穿 孔及幽門閉塞等副作用。這方面的改善,可以增加醫生 使用此類藥物的信心和病人對它的應受性。雖然此類藥 物尚有其他有待解答的問題,但應優先考慮作為治療肌 腱骨骼疾病,特別是在那些容易產生腸胃副作用的病 人。 Introduction Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are frequently used in the management of musculoskeletal pain.1 All traditional NSAIDs inhibit the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, thus prevent the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins (PGs). PGs have different effects in different tissues and organs. In the arthritic joints, they promote pain and inflammation. In the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract, kidney and platelets, they maintain normal functioning of these organs. PGs protect the stomach mucosa, maintain normal renal blood flow in patients with compromised renal function, and maintain normal platelet aggregation. By inhibiting PGs production, traditional NSAIDs are effective in reducing pain and inflammation. But they can also cause UGI side effects, renal and platelet dysfunction. Therefore, they are considered to be "double edge swords".2 Patients' perspective To find out how arthritic patients viewed their conditions, how they perceived available NSAIDs, what medication characteristics were appealing to them, and how they adhered to doctors' suggestions, a national survey was carried out in Canada in 1990.3 Question-naires were sent out to 10,000 homes. Seven hundred and fifty rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and 750 osteoarthritis (OA) patients who were currently on NSAIDs responded. In general, RA and OA patients shared the same attitude towards NSAIDs. "Safety" and "efficacy" were the two most important attributes of NSAIDs. Efficacy was identified by 57% patients as the major reason why they take their NSAIDs, followed by 22% who did so due to lack of side effects, and 20% because of physician endorsement. Of the patients who changed their NSAIDs, 48% did so because of side effects, while 38% did so due to lack of efficacy. Forty-one percent of patients stopped their NSAIDs when they were not in pain, 31% continued to take the medications even if they felt well. Most patients stopped their NSAIDs because of fear of toxicity. This survey demonstrated that patients and physicians share the same concerns on NSAIDs: efficacy and safety. NSAID induced UGI side effects NSAID users may develop three types of UGI toxicities: symptoms, structural lesions, or clinically significant complications. It is estimated that 15-40% patients taking NSAIDs experience UGI symptoms such as dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, bloating, reflux, or abdominal pain.4 On endoscopy, a similar percentage of them were found to have peptic ulcers.5 Most NSAIDs associated upper GI lesions are asymptomatic.6 In one study, almost 60% of NSAID associated peptic ulcers which presented for the first time as a complication requiring hospitalisation have previously been silent. The annual risk of developing a clinically significant UGI complications such as perforation, gastric outlet obstruction, or bleeding for chronic NSAID users was 1.5-2%.7-9 The risk of these complications increases with increasing age, a previous history of peptic ulcer or UGI bleed, and concomitant medical illnesses.7 Misoprostol could reduce NSAID induced UGI complications by 40-60%.7 However, its use is sometimes associated with dyspepsia, bloating or diarrhoea. It is not known whether H2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors are effective in preventing NSAID induced UGI complications. COX-2 specific inhibition In 1989, 2 isoforms of the COX enzymes were identified.10 COX-1 is the constitutive enzyme normally present in the platelet, kidney, and the UGI tract. It controls the production of PGs required for normal physiological functions, such as protection of the UGI mucosa, maintenance of normal renal blood flow and platelet function. COX-2 is usually induced in inflamed tissues by different cytokines or bacterial lipopolysaccharides. It controls the production of PGs which mediate inflammation in the synovium in patients with RA or OA. A small amount of COX-2 however is constitutively present in tissues such as the kidney, brain and bone.10 Drugs which specifically inhibit only COX-2 without inhibiting COX-1 should therefore be beneficial in controlling pain and inflammation without interfering with normal UGI or platelet functions.11 In 1999, celecoxib and rofecoxib, the first COX-2 specific inhibitors, became available for the management of acute pain, OA, or RA, with the promise that they should control pain and inflammation as effective as traditional NSAIDs, but without causing UGI or platelet side effects. Efficacy of COX-2 specific inhibitors Both rofecoxib and celecoxib are effective analgesics. Rofecoxib 50 mg is as effective as ibuprofen 400 mg in relieving pain associated with dental extraction with a longer duration of analgesic action.12 Celecoxib 200 mg as a single dose is as effective as hydrocodone 10 mg/acetaminophen 1,000mg combination in relieving pain following orthopedic surgery. When administered at 200 mg q8h prn, it is more effective and has less side effects than the hydrocodone/acetaminophen.13 Several studies have demonstrated that daily doses of celecoxib 200-400 mg or rofecoxib 12.5-25 mg are as effective as daily doses of ibuprofen 2,400 mg, or naproxen 1,000mg, or diclofenac 150 mg in treating OA patients over 6-52 weeks. Study end points have included not only pain measurement scales, but also a quality of life index, the Western Ontario McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), and a functional index, the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF 36).14-17 In treating patients with RA, celecoxib 200 mg bid is as effective as naproxen 1,000 mg or diclofenac 150 mg daily.18,19 It was also shown that rofecoxib 25 or 50 mg daily is as effective as naproxen 1,000 mg daily in treating patients with RA.20 In summary, both celecoxib and rofecoxib are effective analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. They are as effective as the currently available traditional NSAIDs. Upper gastrointestinal safety of COX-2 specific inhibitors Both celecoxib and rofeco xib have l e s s endoscopically demonstrable UGI ulcers when compared with traditional NSAIDs. In a randomised, placebo controlled study of 1,148 RA patients followed for 3 months, endoscopically demonstrable UGI ulcers were found in 4% subjects taking bid doses of celecoxib 100mg, 200mg, 400 mg, or placebo. On the other hand, patients taking naproxen 1,000mg daily had a significantly higher risk at 28% of having such ulcers.18 Similarly, in a 6 month placebo controlled study of 1,227 OA patients, subjects taking rofecoxib 25 mg or 50 mg daily or placebo had a 4-7% chance of developing an endoscopically demonstrable UGI ulcer. On the other hand, patients on ibuprofen 800 mg tid had a risk of more than 26% of developing such ulcers.21 However, many clinicians are unconvinced that the reduction of endoscopically demonstrable UGI ulcers will translate into clinically meaningful benefits, as the majority of these endoscopic lesions are asymptomatic, and do not evolve into clinically significant complications. To study whether COX-2 specific inhibitors do cause less clinically significant UGI complications when compared with traditional NSAIDs, a meta-analysis of 14 randomised, placebo and active comparator controlled studies on celecoxib treated patients was performed.22 For patients treated with celecoxib 50-800 mg daily, the yearly rate of UGI perforation, gastric outlet obstruction, or bleeding (POB) was 0.18-0.2%. This rate is not statistically different from patients taking placebo, while it is significantly less than the yearly POB rate of 1.7% for patients taking comparator NSAIDs (naproxen 1,000mg, ibuprofen 2,400mg, or diclofenac 150mg daily).22 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 8 randomised, placebo and active comparator controlled studies on rofecoxib treated patients was performed.23 The annual rate of UGI perforation, symptomatic or complicated ulcers, or bleeding (PUB) was 1.3% for rofecoxib treated subjects. This risk of PUB associated with rofecoxib is significantly less than the annual risk of 1.8% for NSAID treated subjects. Recently, the results of two large scale prospective, long-term, randomised, controlled studies: the Celecoxib Long-Term Arthritis Safety Study (CLASS)8 and the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcome Research (VIGOR)9 looking at the UGI complications were presented. CLASS included 7,982 patients with either OA (72%) or RA (28%) with an average age of 60 years. Patients were randomised to take either celecoxib 400 mg bid (n = 3,995), diclofenac 75 mg bid (n = 1,999), or ibuprofen 800mg tid (n = 1,988). Subjects were followed for 6-12 months, with a median of 9 months. Twenty to twentytwo percent of individuals in each group were taking low dose acetysalicylic acid (ASA) (< 325mg daily). VIGOR included 8,076 RA patients with an average age of 58 years. Patients were randomised to take either rofecoxib 50 mg daily (n = 4,047), or naproxen 1,000 mg daily (n = 4,029). Subjects were followed for a similar period of 6-12 months with a median of 9 months. Fifty-six percent of subjects were on steroid. ASA was not allowed in this study. (Table 1)

In CLASS, the yearly risk of POB was 0.8% for patients taking celecoxib, compared with a risk of 1.5% for patients taking ibuprofen or diclofenac, p = 0.09. When symptomatic ulcers were added to the POB, the risk of PUB (perforation, symptomatic and/or complicated ulcers, or bleeding) was 2.0% per year for patients taking celecoxib, compared with a rate of 3.5% for patients taking the comparator NSAIDs, p = 0.03. (Figure 1) Low dose ASA, being a COX-1 inhibitor, can increase UGI bleeding.24 Since low dose ASA is likely to cause an increase in UGI complication in the celecoxib but not in the traditional NSAID group of patients, a secondary analysis excluding the 20% individuals on low dose ASA was undertaken. For patients taking celecoxib alone, (n = 3,101), the POB risk was 0.4% per year, compared with a risk of 1.3% per year for NSAID users, (n = 3,126), p = 0.037. When PUB was analysed, the risk of PUB for celecoxib users was 1.5% per year, compared with a risk of 3.0% per year for NSAID users, p = <0.02.25 (Figure 2) In VIGOR, the yearly risk of POB for patients taking rofecoxib was 0.6% per year, compared with a rate of 1.4% for patients on naproxen, p = 0.005.26

In summary, the reduction of clinically significant UGI complication for both celecoxib and rofecoxib is similar. (Figure 3) Both COX-2 specific inhibitors have a lower risk of UGI complications such as POB and PUB when compared with traditional NSAIDs. While no costbenefit analysis have been carried out, a number needed to treat (NNT) analysis based on the VIGOR study showed that 125 patients would need to be treated with rofecoxib instead of naproxen to prevent one single POB, and 41 patients would need to be treated to prevent one PUB. Similarly, based on the CLASS study, for patients not taking ASA, 100 patients would need to be treated with celecoxib instead of ibuprofen or diclofenac to prevent one single POB, and 67 patients would need to be treated to prevent one PUB.

Both CLASS and VIGOR also demonstrated that celecoxib and rofecoxib were better tolerated than traditional NSAIDs. In CLASS, celecoxib was associated with less UGI symptoms than diclofenac and ibuprofen, including dyspepsia, nausea, abdominal pain, constipation, and withdrawal due to these UGI symptoms. In VIGOR, rofecoxib when compared with naproxen was associated with fewer withdrawals from the study due to abdominal pain, epigastric discomfort, and was associated with fewer UGI symptoms including dyspepsia, abdominal pain, epigastric discomfort, nausea, or heart burn. In a meta-analysis of 5 randomised, double blind, placebo controlled studies, celecoxib 100, 200, 400 mg bidwas found to be superior than naproxen 500 mg bid and was comparable to placebo in causing abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and nausea.27 In summary, the COX-2 specific inhibitors are associated with less UGI adverse events than traditional NSAIDs. The reduction in adverse events include UGI symptoms, endoscopically demonstrable UGI ulcers, and clinically significant UGI complications. Cardiovascular safety of COX-2 specific inhibitors Traditional NSAIDs can reduce platelet aggregation by inhibiting platelet COX-1. COX-2 specific inhibitors do not inhibit platelet COX-1. This raises the question whether patients receiving COX-2 specific inhibitors may have a higher risk of thrombo-embolic events. In CLASS, patients on celecoxib had the same risk of cardiovascular or cerebral vascular events as ibuprofen or diclofenac, including myocardial infarction (MI), any myocardial events, cardiovascular death, and any vascular events. There was less cerebral vascular events in the celecoxib group when compared with the NSAID groups, (0.2% versus 0.5%). (Table 2) Even when the 20% patients taking low dose ASA were excluded from the analysis, there were still no differences between celecoxib and comparator NSAIDs for cardiovascular or cerebral vascular events, including angina pectoris, unstable angina, coronary artery disease, MI, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), thrombophlebitis, and any of these events. In VIGOR, patients taking rofecoxib had the same risk of CVA, cardiovascular death as patients taking naproxen. However, there was a significantly higher risk of MI (0.4%) in the rofecoxib group compared with the naproxen group (0.1%). (Table 3) The reason for the increase in MI is unknown. When the study population was further analysed, 4% patients enrolled in VIGOR actually met criteria for secondary cardiovascular prophylaxis. These included previous history of MI, CVA, transient ischemic attack, angina, coronary artery bypass graft, or angioplasty. Forty-seven percent of the MI occurred in this 4% patients. When this 4% of patients were excluded in a secondary analysis, the incidence of MI in the remaining 96% showed no statistical difference between the rofecoxib (0.2%) and the naproxen groups (0.1%). Secondly, it is possible that naproxen, having anti-platelet effects, can reduce the MI risk compared with rofecoxib. Finally, higher dosage of rofecoxib can be associated with increased oedema and hypertension.11 Since hypertension is associated with increased risk of MI,28 this raises the question as to whether there may be an association between hypertension and the increased incidence of MI in the VIGOR study. However, in VIGOR, only one patient who had MI had hypertension as an adverse event. Celecoxib was not associated with a dose related increase in oedema or hypertension when used in treating RA patients.18 Furthermore, in CLASS, celecoxib 400mg bid was less likely to cause hypertension or oedema than ibuprofen 800 mg tid.

Recently, the results of a direct head-to-head comparison study between celecoxib and rofecoxib were presented.29 Eight hundred and ten hypertensive OA patients over the age of 65 were randomised to take celecoxib 200 mg OD (n = 411) or rofecoxib 25 mg OD (n = 399). Patients on rofecoxib had higher chance of developing oedema (10%) or systolic hypertension (12%) than patients taking celecoxib (5% oedema and 7% hypertension). In summary, rofecoxib may be more likely than celecoxib to cause oedema and hypertension. Although COX-2 is constitutively present in the juxta-glomerular apparatus of the kidney, the oedema and hypertensive effects of rofecoxib are probably not entirely due to renal COX-2 inhibition, as both rofecoxib and celecoxib should equally inhibit renal COX-2. Since COX-2 i s constitutively present in the kidney, COX-2 specific inhibitors should be used with caution in patients with renal insufficiency or with compromised renal blood flow. Other safety issues Traditional NSAIDs may cause relapse of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The effect of COX-2 specific inhibitors in patients with IBD has not been studied. They should therefore be used with caution in these patients. Traditional NSAIDs may cause exacerbation of asthma. COX-2 specific inhibitors should be used with caution in asthmatic patients although a recent report showed the use of celecoxib in patients with ASA induced asthma did not cause increased asthma symptoms.30 Celecoxib structurally contains a sulphonamide side chain. Its manufacturer does not recommend its use in patients with allergies to "sulfa" or sulphanilamide antimicrobial drugs. However, Steven-Johnson Syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with sulphanilamide antimicrobial drugs are due to a reaction to an aromatic amine group attached to the sulphonamide group within the molecule and not to the sulphonamide group itself.31 The sulphonamide group within celecoxib is similar to that of chlorothiazide or furosemide. Unlike the sulphanilamide antimicrobial drugs, the suphonmide groups of these drugs are not attached to an aromatic amine group. It has been demonstrated that individuals "allergic to sulfa" can still take celecoxib without developing allergic reactions.32 In CLASS, celecoxib is associated with a higher incidence of skin rash than ibuprofen or diclofenac (6.2%, 3.7%, 2.8% respectively). However, none of the rash observed was due to Steven- Johnson Syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. In clinical studies, celecoxib was not associated with an increased international normalised ratio (INR) in patients receiving warfarin.33 However, significant elevation in INR had been observed after initiation of celecoxib.34 Therefore, when this drug is used in patients on warfarin, frequent monitoring of INR is essential until the INR is stabilised. Finally, since COX-2 specific inhibitors significantly reduce systemic production of prostacyclin,35 they theoretically can shift the haemostatic balance toward a prothrombotic state. Four patients with connective tissue diseases have been reported to develop ischaemic complications after receiving celecoxib.36 Though these patients had a tendency to develop thrombosis prior to the use of COX-2 specific inhibitor, physicians should be cautious when using these agents in patients with thrombotic tendency. Key messages

S H K Huang, MD, FRCP(C)

Clinical Associate Professor, Division of Rheumatology, University of British Columbia. Correspondence to : Dr S H K Huang, 501-1160 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC Canada V6Z 2E8.

References

|

|