|

March 2001, Volume 23, No. 3

|

Case Report

|

Rheumatology: 2. What laboratory tests are needed?*KShojania HK Pract 2001;23:301-303 The case A 32-year-old woman, consults her physician about generalised aches and pains in her limbs, low back and neck and intermittent headaches during the last 3 years. She experiences fatigue and sleep disturbance. Her hands have always turned red in the cold, and she describes her fingers as sometimes swollen. She has no morning stiffness, alopecia, photosensitivity, psoriasis, skin rash, dry eyes or dry mouth. She has not been able to work as a teacher for the last 4 months. Two years ago, her previous physician told her that, according to blood tests, she probably has systemic lupus erythematosus. She is not taking any medication and is otherwise healthy. A physical examination reveals nothing remarkable except generalised tenderness, particularly in the fibromyalgia tender points. There is no evidence of joint inflammation. Previous investigations, ordered by another physician, included a complete blood count, a urinalysis and thyroid-stimulating hormone and creatinine levels; all were normal. An antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titre of 1:80 with a homogeneous pattern. Rheumatoid factor was positive at a titre of 1:20, complement C3 was 1.75g/L and complement C4 was 0.13g/L. What further investigations, if any, are warranted? To make a preliminary diagnosis of a rheumatic disease the physician must take an extensive patient history and performa thorough physical examination. No screening tests exist for arthritis; thus the "shotgun approach" of ordering a number of laboratory tests for patients with joint or muscle pain can lead to a falsepositive result or canmislead the physician into thinking that there is no rheumatic disease. Most of the common rheumatic diseases such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis,psoriatic arthritis and soft-tissue rheumatism can be diagnosed without laboratory tests. There are a few indications for ordering laboratory investigations to confirm or rule out potential rheumatic disease after a clinical diagnosis is considered. For example, a presumptive diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be ruled out by a negative antinuclear antibody (ANA) test in most cases, and gout or pseudogout can be confirmed by a joint-fluid aspiration. On the other hand, the presence of rheumatoid factor will not confirm or rule out a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Table 1 indicates the usefulness of various laboratory tests for assessing different rheumatic diseases.

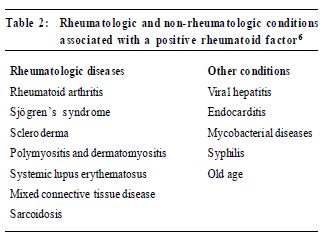

Once a rheumatic disease diagnosis has been made certain laboratory tests can help in assessing prognosis or determining the extent of the disease in various organ systems. For example, for a patient with SLE it would be important to determine the presence of renal disease by conducting a urinalysis and checking serum creatinine levels; a 24-hour analysis of urine protein may be necessary if the urinalysis is abnormal. A poor prognostic sign in SLE is the presence of antibodies to doublestranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), indicating an increased likelihood of major organ involvement (e.g., renal disease or vasculitis). In rheumatoid arthritis the presence of rheumatoid factor at a high titre may correlate with severe, erosive arthritis and an increased risk of extraarticular disease, such as rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis or rheumatoid lung disease. In this case the physician may consider more aggressive disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs such as gold or methotrexate earlier in the course of the disease. Some laboratory tests can assist in the monitoring of certain rheumatic diseases. For example, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be helpful inmonitoring the response to therapy in polymyalgia rheumatica,giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) and rheumatoid arthritis. A common pitfall, however, is to use the ESR as the sole measure of improvement in these diseases. If there is a discrepancy between the clinical response and the ESR, the physician should rely on the clinical response to guide treatment. Finally, some laboratory tests can be used for monitoring potential drug toxicity. For example, monitoring methotrexate therapy will require select hepatic tests (i.e., aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, albumin), a creatinine test and a complete blood count every 4-6 weeks, for cytopenias and macrocytosis. The uses and limitations of specific rheumatologic laboratory tests are described below. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein tests ESR is ameasure of the rate at which red blood cells settle through a column of liquid. Measuring ESR takes approximately 1 hour and is relatively inexpensive compared with the C-reactive protein test. C-reactive protein is produced by the liver during periods of inflammation and is detectable in the blood serum of patientswith various infectious or inflammatory diseases. Use These are non-specific tests that are sometimes helpful in distinguishing between inflammatory and noninflammatory conditions. However, they are not diagnostic and may be abnormal in a vast array of infectious, malignant, rheumatic and other diseases.1 An ESR above 40mm/hmay indicate polymyalgia rheumaticaor giant cell arteritis if the patient's history and physical examination are compatible with either diagnosis. Unfortunately, the ESR may be below 40mm/h in up to 20%of patients with these conditions.2,3 This test may be useful for monitoring patients with rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis,1 where a rise in ESR may herald a worsening of the disease when a corticosteroid dose is being tapered. This should not automatically result in an increase in the corticosteroid dose, but rather closer observation and perhaps amore gradual tapering of the corticosteroid. Common pitfalls Using the ESR to screen for inflammation is usually not helpful because the rate can rise with anemia, infections and the use of certain medications such as cholesterol-lowering drugs. The ESR will also rise with age and is of extremely limited value in the elderly; an elevated ESR in an elderly patient should not prompt further investigation in the absence of clinical findings. The C-reactive protein test is slightly more reliable than the ESR and does not rise with anemia.4 Test for rheumatoid factor "Rheumatoid factor" is a misnomer; it confers a specificity to this test that is not deserved. Rheumatoid factors are immunoglobulinMantibodiesdirected against the Fc (constant) region of the immunoglobulin G molecule. Their presence can be detected with a wide variety of techniques (e.g., agglutination of sheep red bl ood cel ls, lat ex part icl es coat ed with human immunoglobulin G, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or nephelometry). Unfortunately, the measurement is not standardised in many laboratories. Rheumatoid factor is present in most people at very lowlevels, but higher levels are present in 5%-10% of the population, and this percentage rises with age. Use Many conditions can cause an elevated rheumatoid factor (Table 2). Only 60%of patientswith rheumatoid arthritis test positive for rheumatoid factor.5 In a hospitalbased study, the positive predictive value of the rheumatoid factor was only 24%-34%.6 However, for rheumatoid arthritis a high-titre test (³1:512)may predict a more severe disease course. This test should be done only if a patient shows evidence of polyarticular joint inflammation formore than 6 weeks. Serial testing is not useful for patients with rheumatoid arthritis or any other condition.

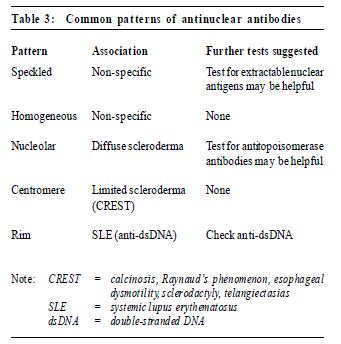

Common pitfalls This test is not useful for screening. It is nonspecific and insensitive – the presence of rheumatoid factor doesnot indicate rheumatoid arthritis,nor does its absence rule out rheumatoid arthritis. Thus, a positive rheumatoid factor in a patientwith non-specific symptoms may precipitate unnecessary investigations. Antinuclear antibody test Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) are diverse, and some have specifi c disease associations. Many of the autoimmune diseases are associated with a positive ANA test. A positive ANA is 1 of the 11 criteria used in the diagnosis SLE.7 This is a useful screening test if SLE is suspected because a negative test virtually rules out SLE. Results are reported as a titre with a pattern (Table 3), which is occasionally useful in making a diagnosis of a connective tissue disease. The ANA test is positive in 98% of patients with SLE, 40%-70% of those with other connective tissue diseases, up to 20% with autoimmune thyroid and liver disease and in 5% of healthy adults (at a cutoff titre of 1:160).8

Use AnANAshould be ordered when a connective tissue disease such as SLE is suspected on the basis of several specific findings on history or physical examination. These findings could include photosensitivity,malar rash, alopecia, mouth ulcers, sicca symptoms, Raynaud's phenomenon, inflammatory arthritisor pleuropericarditis. SLE can usually be ruled out if the test is negative. However, a positive test does not by itself ensure a diagnosis of a connective tissue disease. The ANA is valueless in monitoring disease activity and, thus, does not need to be repeated. Common pitfalls At a cutoff titre of 1:40 a staggering 32% of the general population are positive for ANAs (13% are positive at a titre of 1:80).8 In that only 0.1% of the population have SLE, a low-titre ANA is almost always of no consequence. If the history and physical examination are unremarkable, no further investigation of a positive ANA is necessary. Tests for antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens Extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs) are specific antinuclear antibodies obtained from the blood. There are a large number of ENAs, but most are used for research purposes. Commercially available ENAs include anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Smith, anti-RNP and in some labs, anti-Jo. Use A test for antibodies to ENAs (anti-ENA) should be ordered only if there is a suspected or known connective tissue disease and theANA test is positive at a significant titre (i.e., 1:160 or higher). Many of the anti-ENA tests are helpful if they are positive (Table 4), and some indicat e the possibility of more severe disease manifestations. For example, the presence of anti-Jo antibodies in dermatomyositis often predicts an aggressive course of the disease with interstitial lung disease and inflammatory arthritis.9

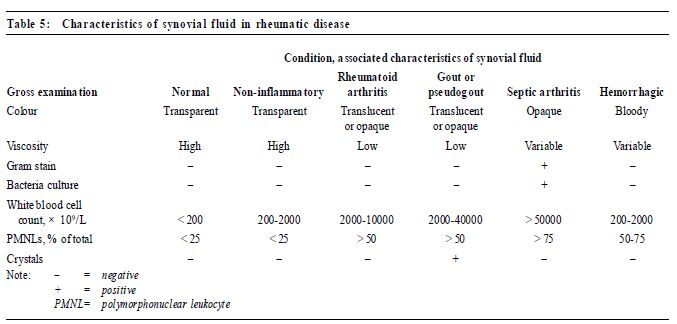

Common pitfalls There are no major pitfalls, although the test is rarely needed and would rarely be ordered by a primary care physician. Negative tests are usually not helpful because most anti-ENA tests have low sensitivity. An exception would be a negative anti-Ro or anti-La result in a pregnant patient with SLE,which may be associated with a lower risk of having a child with neonatal lupus.10 Test for antibodies to double-stranded DNA Antibodies to DNA can be divided into 2 groups: those that react to denatured or single-stranded DNA and those recognising double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). Tests for anti-single-stranded DNA have limited usefulness and are not generally available. In contrast, anti-dsDNA antibodies are relatively specific (95%) for SLE,making them useful for diagnosis.11 A negative test does not rule out the disease, however, because anti-dsDNA antibodies only occur in up to 30% of patients with SLE. Use This test should be ordered only when SLE is suspected after history and physical examinations have been carried out and an ANA test is positive. The antidsDNA test is1 of the 11 diagnostic criteria for SLE,7 and the presence of anti-dsDNA may predict a more severe form of SLE with renal or central nervous system involvement. Some authors12 suggest this test may be useful in following the clinical course of SLE, although this had been disputed.13,14 Most rheumatologists would not treat an isolated rise in anti-dsDNA level in the absence of a clinical flare. Common pitfalls This test should never be performed as part of a routine screening process for patients with aches and pains. Complements C3 andC4 Decreased levels of complement arise from immunecomplex disorders such as SLE, selected forms of vasculitis (e.g., essential mixed cryoglobulinemia and rheumatoid vasculitis), certain typesof glomerulonephritis and inherited complement deficiencies. Use Complement testing is useless for screening but is often used to monitor disease activity in patients with SLE; however, the evidence for the efficacy of this practice is sparse.13 It is expected that an SLE flare will result in decreased complement levels – an elevated complement level is a non-specific finding with no clinical relevance. Common pitfalls Complement levels may reflect disease activity in some patients with known vasculitis or SLE; 10%-15% of Caucasian patients with SLE will have an inherited complement deficiency.15 Repeated testing of these people is not helpful. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) are autoantibodies to the cytoplasmic constituents of granulocytes. They are detected by indirect immunofluorescence on ethanol-fixed neutrophils and produce a characteristic cytoplasmic fluorescence (c-ANCA) or peri nucl ear fluor escence (p-ANCA) . ANCAs characteristically occur in vasculitic syndromes.16 c-ANCAs occur in more than 90%of patients with systemic Wegener's granulomatosis (with renal or pulmonary involvement, or both), 75%of patients with limited Wegener's granulomatosis (without renal involvement) and 50% of patients with microscopic polyarteritis. c-ANCAs are actually antibodies to protein 3. The presence of c-ANCAs is 98% specific for these diseases; changes in c-ANCA levels often precede disease activity and may guide treatment. p-ANCAs occur in a wide range of diseases. They are directed against different cytoplasmic constituents of neutrophils including myeloperoxidase, lactoferrin, elastase and other unspecified antigens,Positive p-ANCA titres are totally non-specific. Only antibodies to myeloperoxidase have significant disease associations. Use The c-ANCA test can be helpful in confirming a diagnosis of Wegener's granulomatosis, microscopic polyarteritisor idiopathic crescentic glomerulonephritis. It has a 98%specificity for these conditions and a high sensitivity for extended Wegener's granulomatosis with renal involvement but is less sensitive for the limited condition without renal involvement. Apositive c-ANCA test in a patient with typical Wegener's granulomatosis may obviate the need for a tissue biopsy. The p-ANCA test is not useful unless it is confirmed by testing for antimyeloperoxidase antibodies,which may occur in several related diseases: Churg-Strauss syndrome, crescentic glomerulonephritis andmicroscopic polyarteritis.17 Common pitfalls A primary care physician will rarely need to order this test; it helps in the diagnosis and management of only a very small number of patientswith relatively rare conditions, and screening patients with non-specific symptoms results in many false-positive p-ANCA results. Serum uric acid test Use This test is helpful in monitoring the extent of hyperuricemia in patientswith gout requiring treatment. The prevalence of asymptomatic hyperuricemia among men is 5%-8%, and fewer than 1 in 3 people with hyperuricemia will ever develop gout.18 Asymptomatic hyperuricemia does not confer a diagnosis of gout and need not be treated unless serum uric acid levels are persistently above 760μ mol/L (12.8mg/dL) for men or 600μmol/L (10.0mg/dL) for women. At these levels there is an increased risk of renal complication.19 Common pitfalls Serum uric acid testing is often ordered for the patient with acute monoarthritis. Unfortunately, this will not be helpful in the diagnosis because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic hyperuricemia and the fact that, in 10%of patients with acute gout, serum uric acid levels are normal. A diagnosis of acute gout can only be made with certainty by joint aspiration to confirm the presence of urate crystals under polarized light. Test for human leukocyte antigen B27 Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27 is present in the blood of 5%-8%of the general population but in 95% of white and 50% of black patients with ankylosing spondylitis.20 This antigen isalso present in 50%-80% of patientswith other seronegative spondyloarthropathies, such as reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome), psoriatic arthritis with spondylitis and spondylitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Use This test is of no value in diagnosing the usual patient with back pain. In addition, it does not usually need to be ordered to confirm a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis although, rarely, it will be helpful in diagnosing patients who have an atypical presentation of this condition.21 Testing for HLA-B27 may be useful for the patient with acute unilateral uveitis who also has inflammatory back pain but no sacroiliitis visible on plain radiographs and for young women with recent onset of inflammatory back pain with no sacroiliitis on plain radiographs. Women with ankylosing spondylitis are more likely than men to have normal plain pelvic radiographs, thereby making diagnosismore difficult. Common pitfalls The routine ordering of HLA-B27 tests for patients with non-specific low-back painwill invariably result in many false-positive results and thus, erroneous diagnoses. Because a first-degree relative of a patient with ankylosing spondylitis has only a 10%-20% chance of ever developing the disease, asymptomatic family members of a personwith ankylosing spondylitis should not be tested for the presence of HLA-B27. A positive test might also limit a person's ability to obtain life or disability insurance. There are no preventative measures to introducewhen an asymptomatic person has a positive test result. Synovial fluid testing Synovial fluid, obtained by joint aspiration, is examined visually for viscosity and tested for cell count and differential,gram staining, bacteria and the presence of crystals under polarized light22 (Table 5).

Polymorphonuclear leukocyte assessment The assessment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in synovial fluid is essential in the investigation of an acute inflammatorymonoarthritis to diagnose septic arthritisor crystal joint disease. A white blood cell count of less than 2000 × 109/L indicates a non-inflammatory effusion. Inflammatory effusions are often accompanied by a white blood cell count of 2000 × 109/L – 50000 × 109/L and infectious arthritis by a white blood cell count over 50000× 109/L,with a predominance of neutrophils. Other tests of value in specific cl inical situations are mycobacteria tuberculosis staining and culture, fungal culture or cytological examination. Ideally, an examination for crystals should be carried out using a fresh sample of synovial fluid, especially to find cal cium pyrophosphate dihydr ate crystals. Monosodium urate crystals seen with gout are needle shaped and strongly negatively birefringent, while the calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals of pseudogout are rhomboid in shape and weakly positively birefringent. Common pitfalls Themost common pitfalls occur when synovial fluid testing is not done. It must be done to make a diagnosis of infectious or crystal synovitis. Gram stains and cultures are not necessary when synovial fluid appears to be non-inflammatory in origin (i.e., transparent and high viscosity) or when septic arthritis is not at all suspected. Chemistry testing (e.g., glucose, lactic dehydrogenase, protein) of synovial fluid is not helpful in making such diagnoses.23 Does the patient require more tests? The patient has no clinical evidence of SLE. According to the history and examination,her symptoms of non-specific aches and pains, sleep disturbance and fatigue are soft tissue in nature. The low-titre positive ANA and rheumatoid factor are non-specific and do not require further investigation. None of these tests needed to be ordered. The patient can be reassured that she does not have SLE; she should enroll in an exercise program for her soft-tissue pain and sleep disturbance; her fibromyalgia might be treated with physiotherapy or amitriptyline. Competing interests: None declared. Key messages

K Shoj ania,

Clinical Assistant Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Univer sity of Br itish Columbia. Correspondence to : Dr K Shojania, 230- 6091 Gilber t Road, Richmond BC V6K 2Y9, Canada.

References

|

|