|

March 2001, Volume 23, No. 3

|

Update Articles

|

The management of hypertension in the acute settingS S WChan Summary This article is an overview of the acute management of hyper tension, based upon a thorough review of three recently updated guidelines from: (i) The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, United States;1 (i i) The Br iti sh Hyper tension Society;2 and ( iii ) the Wor ld Heal th Organi sation – International Society of Hypertension.3 It relates to themanagement approach and the choice of anti-hypertensive agents in acute situations in a rational, evidence-based manner; and is particular ly relevant to primar y care, emergency and family physicians. Introduction Much has been written about the management of hypertension; and many recent updates and guidelines have resulted from scientific studies with consensus of opinions from international experts.1-3 This articlemainly focuses on themanagement of hypertension in the acute situation – the scenario so commonly encountered on a day-to-day basis by doctors in family medicine, primary care, emergency, as well as in many other specialties. The approach of using nifedipine (‘Adalat’) sublingually in response to a certain pre-defined blood pressure reading is still common in Hong Kong, despite serious warnings in theUnited States against thispractice as early as in 1985. A current understanding and a very important concept indeed is that the patient’s clinical presentation is a more important factor to consider in therapeutic decision-making than the absolute systolic or diastolic values. In most cases of acute hypertension, a sudden immediate drop in blood pressure is generally not required,nor desirable.1-5 Hypertensiveemergencies Hypertensive emergencies occur in less than one percent of all hypertensive patients, and the specific pharmacological management of these conditions isnot a primary focusof this article. It requires the ongoing care and expertise of critical care specialists. However, primary care practitioners do need to be able to recognise acute hypertensive emergencies and respond with prompt and appropriate referral. Practitioners need to be able to distinguish between what constitutes a hypertensive emergency from what is simply a hypertensive ‘nonurgency’. The differentiation is mostly clinical, and not simply from the levels of raised blood pressure. Hypertensive emergencies are the most serious complications of hypertension, and these are the only situations in the acute setting that warrant immediate reduction of blood pressure. Thismost serious category is also known asmalignanthypertension,or hypertensivecrisis. Target organ damage is present with acute progression, in syndromes such as intracranial haemorrhage, hypertensive encephalopathies, unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, acute left ventricular failure with pulmonary oedema, dissecting aortic aneurysm, and pre-eclampsia. Hypertensive emergency is currently notdefined according to any absolute range of blood pressure measurements. Instead, it is defined as hypertension with fundoscopic evidence of retinal haemorrhage or papilloedema, and/or evidence of target organ damage. Thus, examination with ophthalmoscope is essential and should not be neglected in assessing a patient with acute hypertension. The treatment goal in acute hypertensive emergencies is the immediate reduction of mean arterial pressure in a controlled manner in order to limit the damage to target organs (brain, eyes, heart, or kidneys). Parenteral anti-hypertensive agents are used specifically in conditions such as hypertensive encephalopathy,pre-eclampsia,pulmonaryoedemaandaortic dissection. An enteral route may be indicated in other situations. The patient's improvement in clinical condition is used as a guide to ongoing therapy. Clinical assessment of patients with acute hypertension Assessment of hypertensive patients is directed towards i) determining the underlying cause; and ii) evaluating the effects of target organ damage. Elevated blood pressure (systolic > 140 mmHg or diastolic >90 mmHg) should be confirmed by repeat measurement in both arms after a period of rest. History History-taking should note any prior diagnosis of hypertension, treatment regimen, compliance and baseline recordings of past blood pressure measurements. Certain dr ugs (e.g. monoamine oxidase i nhi bi t or s or amphetamines) may raise blood pressure acutely. Comorbid illnesses such as congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular or renal disease should be elicited. Features indicating possible end organ damage include CNS symptoms such as headache, diplopia, visual disturbance, mental confusion; cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnoea, palpitations; and renal symptoms such as haematuria and anuria. Physical examination Physical examinati on includes neur ologi cal assessment to detect signsof cerebrovascular accident or encephalopathy, and fundoscopy for retinopathy. As mentioned above, fundoscopic examination is vitally important, yet perhapsmost frequently neglected by the busy practitioner. Cardiovascular examination includes auscultation for carotid bruits, and third and fourth heart sounds. Diminished extremity pulses may suggest coarctation of the aorta or aortic dissection. Abdominal examination may reveal a bruit and a palpable pulsatile mass, suggesting the presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Investigations Further investigationsmay be required depending on the clinical findings. These may include electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiograph (CXR), blood tests for renal function, electrolytes, complete blood picture and urinalysis. The ECG may show evidence of ischaemia,or left ventricular hypertrophy. TheCXR may be helpful in demonstrating congestive heart failure or aortic dissection. Urinalysismay indicate haematuria or proteinuria in the patient with renal impairment. Although most cases of hypertension are considered to be essential with no known cause, the practitioner should be aware of the specific causes that do exist. Important secondary causesof hypertension include renal disease (e.g. renal arteriostenosis, chronic pyelonephritis, glomerulonephritis and congenital polycystic kidneys), coarctation of the aorta, and endocrine causes (e.g. Conn’s syndrome, adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome, phaechromocytoma, and acromegaly). Illicit dr ugs, such as cocaine and amphetamines, and medications such as oral contraceptives, decongestants, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsmay all cause elevated blood pressure. Approachto management As mentioned earlier, a patient with hypertensive emergency should be urgently referred for critical care management. For non-emergency cases, in the acute setting, it is helpful to consider three categories for the management of elevated blood pressure. This will help in answering the important question: ‘to treat or not to treat?

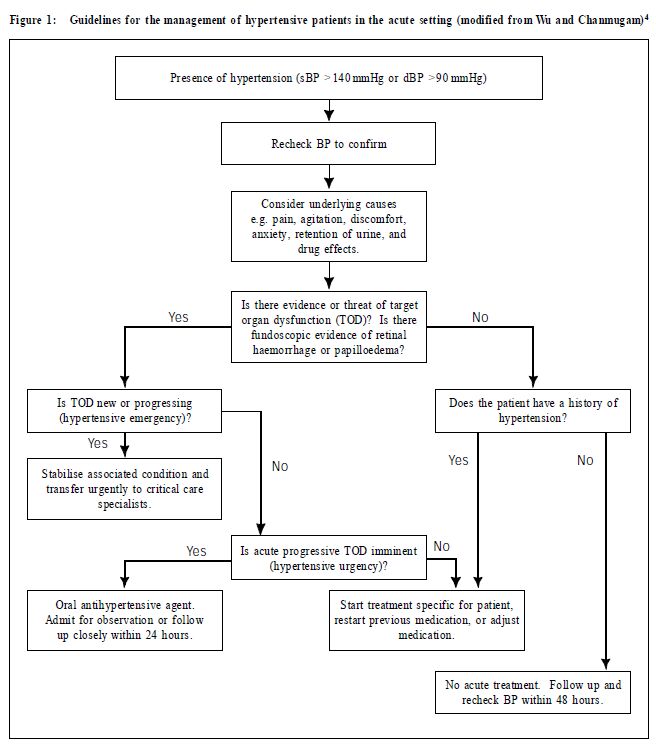

In these patients, acute end organ injury has not yet occurred, but the risk of damage is high if the elevated blood pressure is allowed to persist. In the presence of pre-existing conditions such as chronic renal failure, peripheral vascular disease, retinopathy, coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure, the likelihood of acute progressive target organ damage increases. There is baseline chronic dysfunction of target organs, in impending danger of acute det eriorat ion. The t reatment goal of hypertensi ve ur genci es is to use oral ant ihypertensive agents to reduce the blood pressure gradually within 24 hours. (Note that in the literature, the recommended duration for blood pressure reduction ranges from a few hours1 to 48 hours.)A common cause of hypertensive urgencies is non-compliance to previous treatment, and it is acceptable, in choice of anti-hypertensive agent, to restart the patient on a previously established regime. The patient may or may not need to be treated as inpatient, and this is dependent on the severity of comorbid conditions, age, and the likelihood of compliance to therapy. If managed as an outpatient, follow up should be arranged within 24 hours. Family physicians or primary care practitioners competent in managing hypertensive urgencies can maintain continuity of care, even on an ambulatory basis. The Observation Wards of Accident and Emergency Departments are also suitable for the initial acute management of this condition. The patient has stage 3 hypertension (Systolic >180 mmHg or diastolic >110 mmHg) with no feature of evolving target organ damage. There is no pressing need for immediate reduction of blood pressure (e.g. administration of short-acting sublingual nifedipine) if the patient isasymptomatic. Frequent ly, the patient has been chr onically hypertensive without treatment, and an acute reduction of blood pressure can be deleterious. If the patient has previously been diagnosed to have hypertension, but has been non-compliant to medications, it is reasonable to restart the previous regime and follow up within 24 – 48 hours. In these cases, acute reduction of blood pressure (in terms of hours) has not been shown to be beneficial for longterm contr ol, or for t he chronic effects of hypertension. A patient may have elevated blood pressure associated with painful conditions, anxiety or discomfort (e.g. retention of urine). A phenomenon called white-coat hypertension6 (or “isolated office hypertension”3) is well-reported in the literature, in which the patient gets hypertensive in clinical settings but has normal pressures at other times. Elevated blood pressure recordings on one occasion should never be the basis for diagnosis of hypertension, and should not be an indication for treatment. However, close follow up should be arranged to recheck the blood pressure. Figure 1 gives a summary to the approach of management of hypertensive patients in the acute setting (modified fromWu and Chanmuggam).4 The emphasis is on the clinical presentation and not on the levels of elevated blood pressure measurement. Follow up is essential for all patients. Doctors who do not normally provide continuity of care for their patients with hypertension should refer these patients to the appropriate family physicians or General Outpatient Departments. Advice on life-style modification and assessment of cardiovascular risk-factors areimportant aspectsof follow up management. The decision to initiate drug therapy also depends to a large extent on the presence and severity of cardiovascular risk-factors (e.g. smoki ng, dyslipidaemia,diabetes and family history).1-3

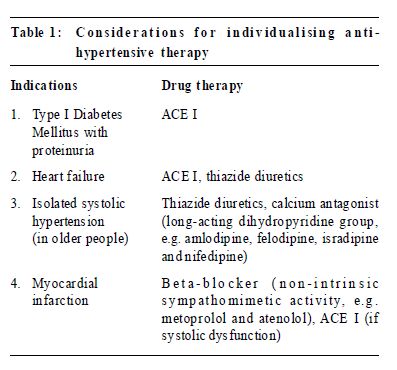

Initiation of drug treatment In the acute setting, initiation of drug treatment is justified in hypertensive urgencies, or in cases when the patient has a history of hypertension but has neglected treatment. Otherwise, anti-hypertensive medications should be started or adjusted for an asymptomatic patient if necessary on follow up assessments.1-5 Therapy for most patients (uncomplicated hypertension) should begin with the lowest dosage to prevent the adverse effect of too great or too abrupt reduction in blood pressure, especially for elderly patients. Ideally, long-acting agents are preferable, to provide 24-hours efficacy on a once-daily basis. The advantage is smoother and more consistent control of blood pressure, which may provide greater protection against the risk ofmajor cardiovascular events and the development of target-organ damage. If the blood pressure remains uncontrolled after 1-2 months, the next dosage level should be prescribed. It may take months to control blood pressure adequatelywhile avoiding adverse effects of medication. It is important to treat the patient and not just the numbers. Choice of agents Thiazide and beta-blockers When the decision has been made to initiate antihypertensive therapy, and when there isno indication for another type of drug, then a thiazide diuretic or a betablocker should be used as first-line. Numerous randomised controlled trials have shown a reduction in morbidity and mortality with these agents.1-3 With the exception of the systolic hypertension-Europe,7 systolic hypertension-China trials8 and the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) study9 from Sweden and Finland,most evidence fromoutcome trialswhich has shown reduction in mortality is for treatment based on thiazide or betablockers. Contraindications and side-effects of these agents should be noted. Thiazides may increase cholesterol, glucose, calcium and uric acid levels, and may reduce potassium, sodium and magnesium levels. Beta-blockersmay cause bronchospasm or bradycardia, mask symptoms of insulin-induced hypoglycaemia and impair peripheral circulation. Other alternatives Three long-termdouble-blind studies have compared the major classes of anti-hypertensive drugs (thiazide diuretic, beta-blocker, calcium antagonist, angiotensinconverting- enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, and alpha-blocker), and overall,no consistent or important differences in antihypertensive efficacy, side-effects or quality of life were found.10-12 Few trials have compared different drug classesdirectlywith respect to reduction in cardiovascular events with convincing results.2,13 As there isno evidence of superiority in anti-hypertensive efficacy or tolerability of the alternative agents (ACE inhibitors and calcium antagonists) over thiazides or beta-blockers, and since these alternative drugs are widely used as first-line therapy,more studies are needed to confirm that they also reduce overall long-term morbidity and mortality, as has been shown for thiazides and beta-blocker. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors These are safe and effective agents, and are now much less expensive than when first introduced. They have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality when the patient has heart failure.14 They are also particularly effective in retarding the progress of renal disease in patients with Type I diabetes, and for patients with diabetic nephropathy with proteinuria.15 Their most common side effect is dry cough. Angio-oedema, though rare, is a serious life-threatening adverse effect. Despite the guidelines recommendations,1-3 many experts do maintain that the beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors on the heart, the kidney, and even the eyes16 are so pronounced and the incidence of their side effects so low that it seems more than reasonable to use them as an initial treatment of uncomplicated hypertension.17 It is contraindicated, however, in patients with renal artery stenosis; and there is an increased risk of adverse effects in patients with chronic renal failure and collagen vascular disease. Nifedipine All of the recent guidelines1-3 have stressed that short-acting nifedipine should be avoided in the treatment of any form of hypertension. As early as 1985 the Food andDrugAdministration (FDA) of theUSA had reviewed data regarding the use of sublingual nifedipine for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies, and concluded that the practice should be abandoned because it was neither safe nor efficacious.18 Short-acting nifedipine has never been approved by the FDA for the treatment of any form of hypertension, accelerated or mild. It is not recommended for treatment of true hypertensive emergencies because its absorption is unpredictable.18 Over the years its use has since gradually declined in theUS, but it seems to be still rather common in Hong Kong. The literature is fraught with reports of serious adverse effects with sublingual or oral short-acting nifedipine, as reported in a review by Grossman et al.18 These reported adverse effects included myocardial ischaemia or infarction, ischaemic strokes and syncope. Recent meta-analysis and case-control studies have further shown a statistically significant association between the use of short-acting calcium antagonist and an increased risk of myocardial infarction, cardiovascular event and mortality.19-21 However these findings should not be extrapolated to the long-acting slow-release formulations of nifedipine and other calcium antagonists, which are approved by the FDA for anti-hypertensive therapy.21-23 There are several situations inwhich definite benefits are demonstrated for the choice of particular antihypertensive agents. Table 1 shows the compelling indications suggested by the National Institutes of Health1,24 of the United States for these classes of antihypertensiveagents.

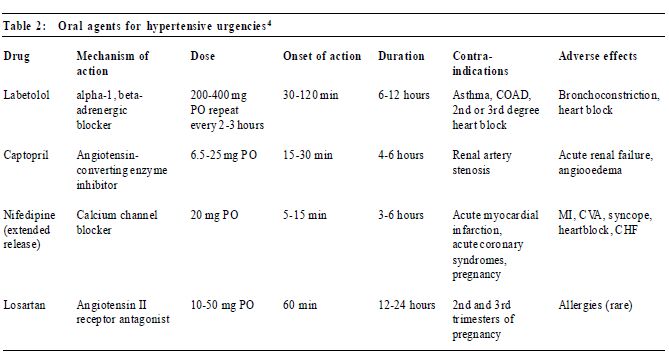

Hypertensive urgencies The choice of oral agents for hypertensive urgencies includes captopril, labetolol, slow-release nifedipine, and losartan.4 Again, short-acting nifedipine, whether sublingual or oral, is not recommended. (Table 2)

Conclusion Hypertension is a common condition and every practitioner should be able to manage the acutely hypertensive patient based upon sound concepts and acceptable standards of care. It is hoped that this short review can provide fundamental guidelines, and that enough interest is generated for more in-depth studies of the topic. Key messages

SS WChan, MBBS( Syd),FRCSEdin(A&E),FHKCEM,FHKAM(Emerge ncyMedicine)

Senior Medical Officer, Depar tment of Accident and Emergency, Pr ince of Wales Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr S S W Chan, Depar tment of Accident & Emer gency, Pr ince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, N.T. , Hong Kong.

References

|

|