|

May 2001, Volume 23, No. 5

|

Update Articles

|

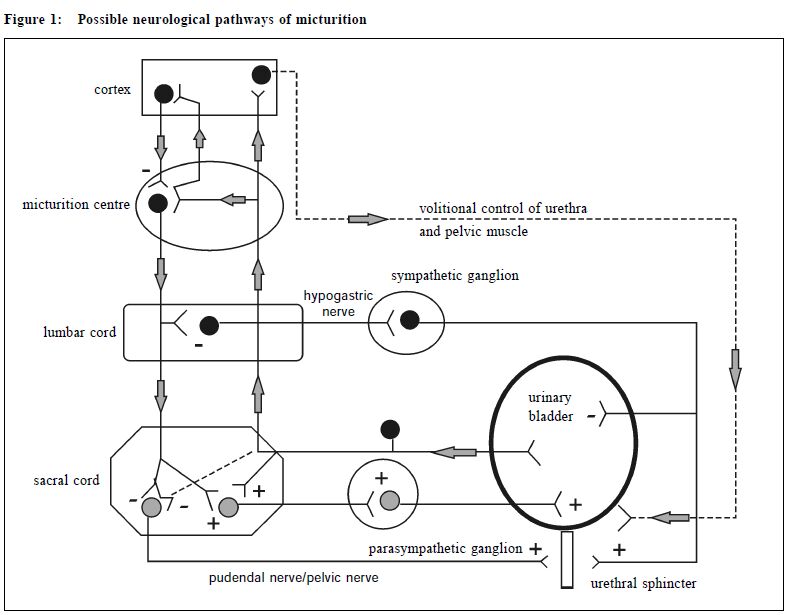

Incontinence in elderly – a complex problem with a simple presentationJ K H Luk 陸嘉熙, C K W Pei 邊其偉, F H W Chan 陳漢威 HK Pract 2001;23:201-207 Summary Urinary incontinence is common in older persons. The neurological innervation and neuropharmacology of the lower urinary tract are complex and are not completely understood. Good history taking, targeted physical examination, simple bedside and laboratory tests are enough to establish diagnosis in many cases. Urodynamic study is helpful in patients with diagnostic difficulty. Transient causes of incontinence should be identified and treated promptly. The differentiation of various types of established incontinence is essential to develop appropriate management strategies. Nonpharmacological treatment can be offered first followed by drugs. Occasionally surgery is needed in resistant cases. Restoration of continence should be the aim for every incontinent older patient. 摘要 小便失禁問題在老年人中較為常見。下泌尿道的 神經分佈和神經藥理機制很複雜,尚未被完全了解。 通過詳細的病史採集、針對性的體檢、簡單的臨床檢 查和實驗室檢驗,大部份的病例都可以作出正確的診 斷。尿動力測試可以幫助診斷困難的病例。對於暫時 性小便失禁的病因應作出及時的診斷和治療。小便失 禁的不同類型要清楚地區分,繼而作出正確的治療對 策。藥物治療之前應先進行非藥物治療。若藥物和非 藥物治療都不能改善失禁的情況,可以考慮採用手術 療法。我們應以恢復老年失禁患者的小便控制能力為 治療目標。 Introduction Urinary incontinence is a common problem of the elderly people in Hong Kong.1,2 It is associated with pressure ulcers, skin irritation, bone fractures and falls. Psychologically, it leads to anxiety, depression, embarrassment and isolation. Socially, it leads to carer stress and institutionalisation.3 Hence, family physicians should have a good understanding of this problem so as to develop appropriate management plans for the patients. The anatomy of the lower urinary tract The bladder neck and urethral mechanisms are important components of the sphincter mechanism. There is a well-defined collar of smooth muscle around the bladder neck in male but not in the female. This explains why bladder neck incompetence is more common in female than male. The urethral mechanism is formed by the involuntary striated muscle at the distal prostatic urethra in male and in the middle third of female urethra. The intra-abdominal urethral segment contributes to continence maintenance by allowing changes in intraabdominal pressure to be transmitted to this segment. In woman, the frequent displacement of the urethra due to weakening of supportive ligaments results in loss of the intra-abdominal urethral segment. This explains why female is more prone to stress incontinence. The neurological innervation of lower urinary tract The possible human neurological pathways are shown in Figure 1.4 The parasympathetic nerve stimulates bladder contraction while the sympathetic system inhibits bladder contraction and activates urethral sphincter to delay micturition. The activity between the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems is coordinated by the pontine micturition centre, which in turn is under the control of the cerebral cortex. There is also a volitional pathway to delay voiding in socially inappropriate situation.

Neuropharmacology of bladder smooth muscle Muscarinic cholinergic receptors are present in the bladder wall and a sustained bladder contraction follows parasympathetic stimulation of these receptors.5 The adrenergic receptors in the bladder are mainly beta-2 and alpha-1 receptors. The alpha-1 receptors are excitatory while beta-2 receptors are inhibitory. There are more beta receptors than alpha in the bladder wall. On the contrary, the bladder base and proximal urethra contain predominantly alpha receptors. Non-adrenergic and non-cholinergic (NANC) sensorimotor nerves also exist in bladder. They consist of a number of putative neurotransmitters, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP), prostaglandins (F2, E, E2), opioids, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), substance P, neuropeptide Y, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), amines and amino acids.6-12 The exact role of the NANC in human bladder is not totally understood. Types of incontinence Urinary incontinence can be classified according to the clinical presentations into: urge, stress, overflow and functional. (Table 1) Alternatively, incontinence can be categorised according to its etiology into: transient, and established.

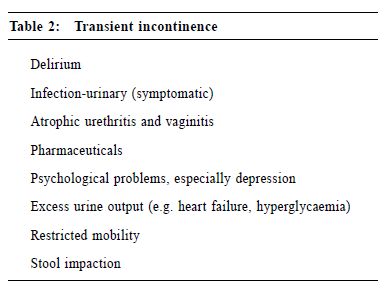

Transient incontinence The word DIAPPERS is useful in helping physicians to rule out the possible reversible causes of transient incontinence (Table 2).13 Transient incontinence is common in community-dwelling and acutely hospitalised elderly.14 Albeit transient, the causes of incontinence may persist if untreated, leading to established incontinence.

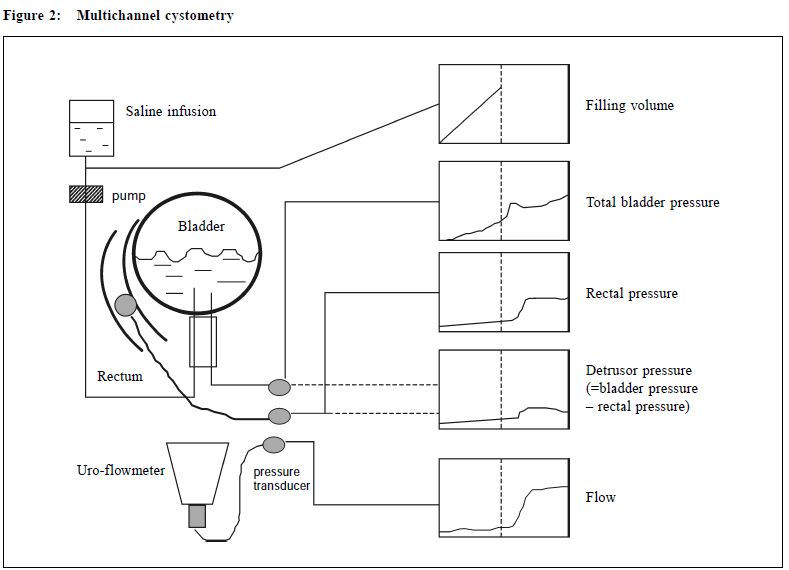

Established incontinence Established incontinence includes detrusor overactivity, stress incontinence, outlet obstruction, detrusor underactivity and functional incontinence. Detrusor overactivity presents with urge incontinence and is the most common cause of established urinary incontinence.15 Detrusor overactivity is further classified into detrusor hyperreflexia, or detrusor instability. Detrusor hyperreflexia describes the occurrence of an uninhibited bladder due to central nervous system lesions including stroke, Parkinsonism, dementia, cervical cord disease and multiple sclerosis.16-18 Non-neurological causes such as aging, urethral obstruction, urethral incompetence, bladder stone and bladder carcinoma are associated with detrusor instability. In fact, a demented old man may have detrusor overactivity due to both detrusor hyperreflexia and instability as a consequence of aging, dementia, prostatic hypertrophy with urethral obstruction and old stroke. Detrusor overactivity in elderly actually exists as two subsets, one in which contractile function is preserved, and in the other contractile function is impaired. The latter one is termed detrusor hyperactivity and impaired contraction (DHIC).19 DHIC is the most common form of detrusor overactivity in the elderly.15 The recognition of DHIC in clinical practice is important as treatment of urge incontinence with anti-cholinergic agents can be complicated by urinary retention if DHIC is present. Stress incontinence is more common in older women and is usually due to pelvic muscle laxity, previous operative trauma and atrophic vaginitis. In men, sphincter damage complicating prostectomy is the major cause. Outlet obstruction with overflow incontinence is the second most common cause of incontinence in older men. In women, fibrotic changes associated with atrophic vaginitis can lead to urethral stenosis. Occasionally, it is due to kinking of the urethra after bladder neck suspension or a large cystocoele. Patients with detrusor underactivity often present with overflow incontinence.20 Detrusor underactivity is associated with diabetes neuropathy, alcoholism, tabes dorsalis, spinal cord lesion, early phase of stroke or long standing obstruction. Idiopathic cases are also common. Functional incontinence refers to incontinence despite a normally functioning lower urinary tract. It is associated with depression, dementia, psychiatric illnesses and immobility. We should rule out other reversible causes of incontinence before labelling incontinence as functional. Evaluation of incontinence in elderly The main objectives of evaluation are to identify reversible conditions, develop a targeted management plan and determine the need for further investigation. History should focus on the characteristics of the incontinence, current medical problems, medications, and impact on patients and caregivers. Bladder records are helpful to characterise symptoms and follow the response to treatment. Physical examination should include checking for signs of neurological disease, per vaginal examination and rectal examination. Stress testing is by asking the patient to cough to observe for any leakage of urine in the upright posture. The presence of leucocytes and/or nitrites in urine dipstick testing should alert physicians about the possibility of urinary tract infection. Urodynamics When history, physical examination, and simple tests are insufficient to make an accurate diagnosis, urodynamics are helpful.21 Usually, multichannel cystometry, including filling and voiding cystometry, is performed (Figure 2). A catheter is inserted into the rectum to record the abdominal pressure. Two catheters are inserted into the bladder for saline infusion and intravesicle pressure measurement (detrusor pressure = bladder pressure – abdominal pressure). The bladder is filled with normal saline and the patient is asked to report when the first desire to micturate and the strong desire to void occur. After the bladder is full, the patient is asked to void. The volume, pressure and flow rate tracings during the procedure will be recorded by the machine computer. If radiological facilities exist, videocystometry can be performed in which contrast media is used to visualise the bladder and outflow tract during cystometry. Videocystometry is used to assess complex cases where equivocal results have been obtained from simple cystometry.

Management Behavioural therapy Pelvic floor exercise is useful in treating stress and urge incontinence.22 Biofeedback can be done in conjunction with pelvic floor exercise. It involves the use of bladder, rectal or vaginal pressure recordings for proper pelvic floor muscle contraction and relaxation training.23 Electrical stimulation has been tried in stress and urge incontinence but evidence of its effectiveness is still conflicting.24 Bladder retraining is effective for subjects with good motivation and adequate cognitive function, with stress and urge incontinence. It usually involves progressive lengthening or shortening of intervoiding intervals.25 Toileting procedures involving the application of timed voiding and prompt voiding are suitable for more dependent and less motivated subjects. In timed voiding, routine toileting at regular intervals is offered to the clients. Prompt voiding implies the offering of opportunity to toilet at regular intervals with positive reinforcements for continent voids and neutral remarks for incontinent episodes. Drugs Drugs commonly used in incontinence include bladder relaxants, bladder stimulants, alpha agonists and antagonists.26 Anticholinergic agents such as oxybutynin and tolterodine can reduce the strength of the detrusor contraction and are effective in treating urge incontinence. Alpha- adrenergic antagonists can reduce bladder overactivity (due to altered receptor function) as well as reducing outlet resistance. Stress incontinence may be t r eated by alpha-adrenergic agonists such as phenylpropanolamine to increase outlet resistance. Bladder emptying may be facilitated in patients with overflow incontinence by parasympathomimetics like bethanecol or distigmine. In postmenopausal women with atrophic vaginitis and urethritis, systemic or topical oestrogen replacement reduces urge and stress incontinence. Surgery Surgery has a role in the treatment of stress and urge incontinence if other non-surgical methods have failed.27 If urethral hypermobility is confirmed in stress incontinence, anterior vaginal repair, retropubic suspension and needle suspension can be tried to reposition the urethra. Clam ileocystoplasty is at present the surgery of choice for management of overactive bladder. In this procedure, the bladder is bivalved in the coronal plane, giving it the appearance of an open clam. A length of the ileum with its own blood supply is then sutured to the bladder. This results in a larger bladder with ineffective involuntary contractions. Others Supportive devices available commercially include disposable diapers, disposable adult briefs, reusable briefs with disposable pads, and absorbent bed protectors. The use of bedside commodes, bed pans, urinals and external collecting devices can also be helpful to minimise the impact of incontinence. Simple dietary or drug modifications are often helpful to reduce the severity of incontinence. For instance, a patient with nocturia and incontinence at night is advised against drinking water just before going to sleep. If he is on diuretics, a smaller dose given in the morning is desirable to reduce nighttime diuresis. The challenge of elderly incontinence Incontinence should not be regarded as a natural phenomenon when one becomes old. The diagnosis is often crippled by the reluctance of the patients to openly discuss their incontinence problems with the doctors. In addition, the management depends more on the attitude of doctors than on their knowledge. An elderly subject can achieve a better quality of life and function if continence can be maintained. Restoration to continence should be the aim for every elderly incontinent patient. Key messages

J K H Luk, MBBS(HK), MSc, MRCP(UK), FHKAM(Medicine)

Senior Medical Officer, C K W Pei, MBChB, MRCP(UK), FHKCP, FHKAM(Medicine) Senior Medical Officer, F H W Chan, MBBCh(Wales), MSc(Wales), MRCP(Ireland), FHKAM(Medicine) Consultant (Geriatrics), Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Fung Yiu King Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr J K H Luk, Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Fung Yiu King Hospital, 9 Sandy Bay Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|