|

November 2001, Volume 23, No. 11

|

Original Article

|

|

A training course to promote evidence-based clinical audit in primary care in Hong KongR Baker, K Khunti, C Y Tsang 曾昭義 HK Pract 2001;23:484-489 Summary Objective: To evaluate a training course for primary care professionals on evidence-based audit. Design: A five-day course was developed and delivered to introduce the principles and practicalities of evidence-based audit. Questionnaires were administered to participants before and after the course, and participants of the first course reported the audits they had conducted in the year following the course. Subjects: Forty course participants, including 16 physicians from general outpatient clinics, 11 family medicine physicians, 7 other physicians and 6 other primary care professionals. Main outcome measures: The level of confidence of participants in conducting an audit reported before and after the course, and the audits undertaken by the participants of the first course. Results: Participants reported increased confidence in their ability to conduct audit, use the Cochrane Library, develop review criteria, collect data and implement change. Of the 20 participants on the first course, 17 presented the audits they had undertaken. Conclusion: The course improved participants knowledge of and confidence in evidence-based audit. It was also followed by the conduct of good quality audits. With suitable training and appropriate support from service managers, it is possible to implement effective evidence-based audit in primary care in Hong Kong. Keywords: clinical audit, family physician, training 摘要 目的: 評估一個實證醫學審計訓練課程的成效。 設計: 為期五天的課程,主要是實證醫學審計的原則和運用。課程之前和之後,參加者要填寫問卷,首期學員要在學完後一年內交審計報告。 對象: 共有40名學員,包括16位普通科醫生,11位家庭醫學醫生,7名其他科醫生和6位其他提供基層醫療的醫生。 測量內容: 課程前後對於進行審計的信心,以及有學員的審計報告。 結果: 參加者對於進行審計,使用Cochrane Library,制定評估標準,數據收集和落實改善工作能力的信心有所增強。20位首屆學員中有17人提交了審計報告。 結論: 課程可以增加參加者的知識和實證醫生審計的信心和能力。通過適當的訓練和上司的支持。香港基層醫療服務範疇內進行有效的實證醫學評估是有可能的。 主要詞彙: 臨床審計,家庭醫生,訓練 Introduction In the health care systems of most countries, the development of efficient programmes of primary health care and the implementation of effective quality improvement are regarded as priorities. Hong Kong is no exception in this respect, and both were key components of a recent study commissioned to review the existing health care system and to recommend necessary changes (the "Harvard Report").1 In response to the findings of this review, the Health and Welfare Bureau published a consultation document on health care reform.2 The general aims of the proposed reforms were to create a health care system that promotes health, provides holistic care, enhances quality of life and enables human development. Key features of the proposals included the re-organisation of primary care and improved quality assurance mechanisms, including clinical audit. The changes suggested to improve primary care involved an increase in the number of qualified family medicine specialists and the transfer of the Department of Health's general outpatient service to the hospital authority following which the service would be redesigned to concentrate on the financially vulnerable. To extend quality assurance, the regulatory system was to be reviewed, the complaints system strengthened, and health professionals encouraged to take part in quality improvement activities. These activities included the use of clinical protocols, a system of clinical supervision, and clinical audit, supported by a newly created research office to assist the administration in collecting data, identifying problems and assessing priorities. Clinical audit has also been promoted in primary care in the UK, and resources to support the activity were first made available from 1991.3 Since then, many health professionals have taken part in audit although the impact has been variable.4,5 In view of this experience, a more comprehensive quality improvement system referred to as clinical governance was introduced from 1999.6 Clinical governance incorporates clinical audit, but also includes steps to support evidence-based clinical practice, along with risk management systems, life-long learning and strengthened accountability.7 The UK experience has lessons for the introduction of audit in Hong Kong, and therefore a course was designed to help practitioners in Hong Kong in developing their own expertise in audit. In this paper, we report the delivery and evaluation of the course. Methods The course The course has been delivered twice, the first time in 2000 and the second in 2001, each course lasting five full days. Twenty participants attended each course. The course aims were to:

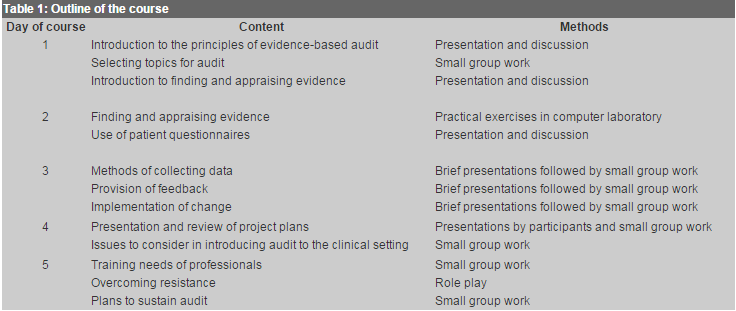

A course manual was prepared that included copies of published papers to be read before the course and extracts from the course book, Evidence based Audit in General Practice: from principles to practice.8 The teaching methods were a combination of didactic presentation, interactive sessions, small group work and role play.

An outline of the course content and teaching methods is shown in

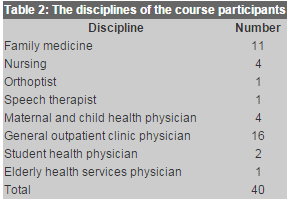

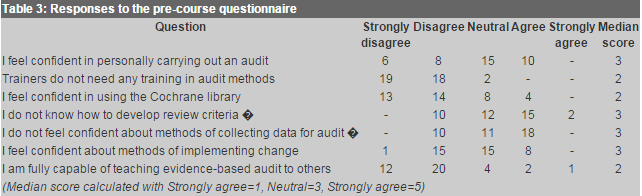

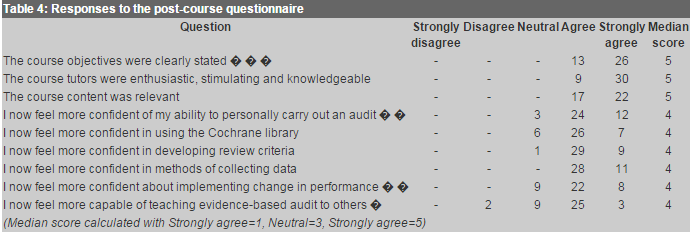

Evaluation In order to assess the immediate impact and acceptability of the course, participants were asked to complete questionnaires. A questionnaire was administered at the start of the course and another at the end. The pre-course questionnaire included seven questions and sought participant's perceptions of their ability to undertake audit, develop review criteria, use the Cochrane library, collect data, implement change and teach audit to others. The post-course questionnaire included nine questions about the participants perceptions of the course objectives, the performance of the tutors and relevance of content, and abilities in undertaking audit, using the Cochrane library, developing review criteria, collecting data, implementing change and teaching evidence-based audit to others. Responses in both questionnaires were in the form of five options from strongly agree to strongly disagree. To further assess the long term impact of the course, the participants of the first course were asked to present any audit they had done in the past year to the second course in 2001. Results A total of 40 participants attended the courses (Table 2). The course was generally evaluated positively by the participants. They increased their understanding of evidence-based audit and how it may be used and taught (see Tables 3 and 4). In particular, participants reported being more confident in undertaking audit, including use of the Cochrane library, developing criteria, collecting data and implementing change. There was also some increase in perceived ability to teach evidence-based audit to others.

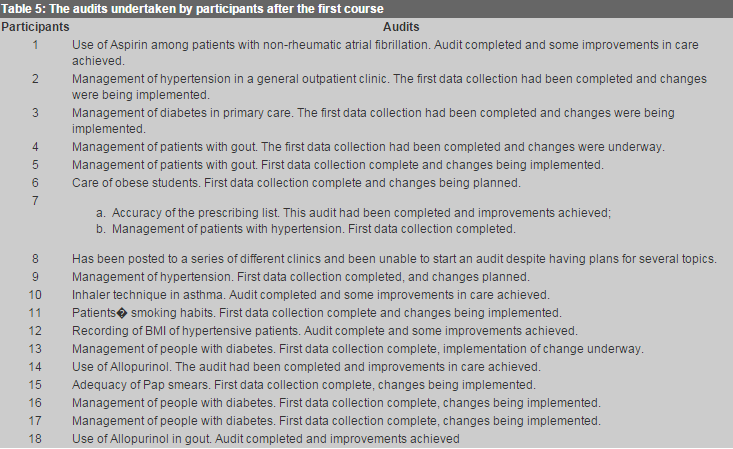

Our evaluation took place at the conclusion of the second course, and therefore the participants of the second course had not had time to begin their own audits. Of the 20 participants in the first course, 18 returned to present the audit work they had undertaken in the year since they had attended the course. Of the two who did not present, one had been seconded from clinical practice to the Department of Health and the other was on holiday at the time of the second course. Only one of the 18 had not been able to undertake an audit, the reason being frequent relocation to different clinics. The projects are summarised in Table 5.

Discussion We have reported an evaluation of a course to teach professionals in primary care the principles of evidence-based audit. A mix of professional groups attended the course, and the findings indicate that participants did increase their knowledge of audit and their confidence in undertaking audit. The reports of audit projects undertaken by participants of the first course support this conclusion, since most of them had undertaken audits in their clinical settings, and those that had been completed demonstrated improvements in the quality of care. The course participants demonstrated considerable enthusiasm and industry. Their attitude should serve as encouragement for the plans of the Department of Health to introduce clinical audit in primary care as part of the recommendations to implement quality improvement activities. Our findings suggest that the provision of training is an important step in implementing clinical audit in primary care. It is difficult for individuals to undertake audit if their colleagues in the workplace do not appreciate the function or methods of audit. In the long term, therefore, a greater number of people trained to undertake evidence-based audit will be required. Furthermore, clinical services must be aware of the need to develop audit and provide the necessary support to teams and individuals who use audit to improve the quality of care. For example, facilities and information systems in primary care services did not present insurmountable obstacles to the participants undertaking audit, but improved record systems would be desirable in the future. A number of factors contributed to the impact of the course. First, the provision of protected time for five days enabled participants to consider audit in depth. In particular, the format allowed positive attitudes to quality improvement to develop, and for ideas to be exchanged between participants about how audit could be implemented despite the pressures facing professionals in primary care. Second, considerable time was spent in small groups, during which participants gave thought to developing their own projects. In consequence, the potential problems in undertaking particular projects could be aired and addressed. In addition, networks formed to enable participants to support each other in undertaking audit in the months following the course. Third, the use of the computer laboratory enabled participants to gain practical experience of using resources for finding research evidence. Many participants had limited confidence in these methods prior to the course, but discovered that the resources available (for example the Cochrane library), are easy to use and offer good quality information. Some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. The evaluation was based on the self-reports of participants, and they may have over-estimated the impact of the course, however, the information presented about the audits undertaken by the participants of the first course does indicate that the course had a longer term and practical outcome. The course has included participants selected because of their interest in developing the ability to undertake audit, and therefore it cannot be assumed that professionals disinterested in audit would benefit. Nevertheless, the findings confirm the impact of the course among interested professionals, and point to the potential of audit to improve services in primary care in Hong Kong. Acknowledgment: We thank the Department of Health who funded the course.

R Baker, MD, FRCGP Director, K Khunti, MD, FRCGP Lecturer, Clinical Governance Research & Development Unit, Department of General Practice, University of Leicester. C Y Tsang, MBBS(UNSW), FRACGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine), DFM(CUHK) Consultant, Department of Health.Correspondence to:Professor R Baker, Clinical Governance Research & Development Unit, Department of General Practice & Primary Health Care, University of Leicester, Leicester General Hospital, Gwendolen Road, Leicester, LE5 4PW, UK. References

|

||