November 2001, Volume 23, No. 11 |

Update Article

|

|

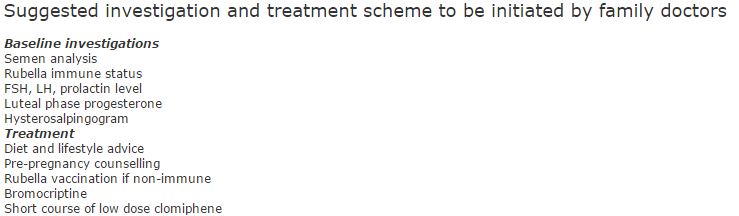

Management of subfertilityH F Tung 董曉方,K M Chow 周鑑明,L C Ho 何樓章 HK Pract 2001;23:495-501 Summary Ten percent of the local population have problems in conceiving. Management varies from simple lifestyle advice to sophisticated micromanipulation with assisted reproductive techniques. Appropriate investigation and counselling alleviates the patient's anxiety and enables efficient referral to the relevant specialist. 摘要 隨著各種人工輔助生殖技術的應用,許多不孕的夫婦可以達成妊娠的心願。主要適應症包括輸卵管阻塞、排卵障礙、子宮內膜異位症、男性弱精及不明原因不孕。 婦女年齡是成功受孕的一個重要因素。家庭醫生在及早診治和轉介方面擔當重要的角色。 Background The development of techniques in reproductive medicine in the past twenty years has dramatically changed the life of many subfertile couples and the practice of doctors. Many couples once considered infertile can now conceive with assistance. Family doctors remain their first contact when they have problems. Pre-pregnancy advice Diet Women who are planning for pregnancy should have a balanced diet with folic acid supplement before conception and during the first 3 months of pregnancy. The recommended daily consumption of folate is 400mcg to prevent neural tube defect. A dose of 5mg should be given if there is past history of neural tube defect or if the patient is on anti-epileptic drugs. Minerals and vitamins such as vitamin E and C have been used to treat male infertility. However, their efficacy is not established. Weight Women with normal body mass index (between 20-25kg/m2) are more likely to have normal pregnancy. Obese women tend to be anovulatory and have higher risks of complications such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome during treatment. Underweight women may also be anovulatory and amenorrhoeic. They tend to have lower birth weight babies. Alcohol and smoking Smoking can cause oxidative damages to oocyte and morphological sperm abnormalities. Alcoholism causes impotence and disturbs testosterone metabolism and ovulation. Excessive consumption during pregnancy leads to fetal alcohol syndrome. Age Age is the most important determinant.1 For women less than 25 years old, cumulative conception rate at 6 months of unprotected intercourse is 60% and at 1 year is 85%. For those older than 35 years of age, cumulative conception rate is 60% at 1 year and 85% at 2 years. Thus the fecundity is halved. Not only is the fecundity affected by age, the risk of congenital abnormalities also increases with maternal age. Hence if there is fertility problem, investigation and treatment should not be delayed especially if the female partner is of advanced age. Rubella vaccination All women contemplating pregnancy are advised to check their rubella immunisation status and to have vaccination if they are not immune. Sexual behaviour Coital frequency less than twice per month may cause reduction in fertility. Abstinence until the day of ovulation should be avoided as it is detrimental to sperm function. The optimal coital frequency would be every 2-3 days during the follicular phase and around the day of ovulation. Investigations When to start? Couples with difficulties in conceiving should be offered proper counselling. Couples who cannot conceive after one year of unprotected coitus should be offered an infertility work-up and treatment. Tests for ovulation Women with regular 28-30 days menstrual cycles have 95% chance of having ovulatory cycles. Basal body temperature (BBT) chart can help to detect ovulation, because progesterone in the luteal phase will raise BBT by 0.2-0.4°C. However, apart from causing stress, it has a high false negative rate. Ten percent of women who are ovulatory have a monophasic pattern. A day 21 progesterone level of 30nmol/L or more suggests ovulation. But if the patient has an irregular cycle, it is difficult to know when to perform the test. Sometimes it may be necessary to take two progesterone measurements in the same cycle or aid with serial ultrasound monitoring. In natural cycles, a dominant follicle appears on day 5 and it grows at a rate of 2-3mm per day to 16-18mm on the day of ovulation. Tests for tubal patency Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a reliable test for tubal patency. It is usually performed at the follicular phase of the cycle (within 10 days of last menstrual period). A water-soluble contrast medium is injected into the uterine cavity while x-ray imagings of the pelvis are taken. It is relatively non-invasive and can provide valuable information about the uterine cavity and tubes. Complications such as allergic reaction and infection are rare. Tubal spasm can occur, leading to a false positive result of blocked tube. This can be avoided by slow injection of contrast or by giving glucagon. A higher pregnancy rate is noticed among patients who have undergone diagnostic HSG, and this leads to the speculation of the therapeutic effect of this procedure. The mechanism is unknown, but dislodgement of a mucus plug in the fallopian tube has been suggested. Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy Laparoscopy is the 'gold standard' for investigation of tubo-peritoneal factor.2 The uterus, the bowel and the Pouch of Douglas are inspected. The liver surface is examined for any adhesions from previous inflammatory disease. The ovaries are inspected for signs of ovulation, endometriosis or other pathology. The ovarian fossa is a common site of endometriotic tissue deposition. Filmy adhesions should be lysed. Methylene blue is then injected transcervically and the spillage of dye can be observed at the fimbrial ends of fallopian tubes via the laparoscope. The severity of tubal damage and adhesion can be graded using different scoring systems to give some indication of prognosis. Hysteroscopy should be performed if there is any suspicion of intracavitary lesion by HSG or ultrasound scan. Diagnostic laparoscopy is a simple procedure, but it also carries risks of bowel injury, and a risk of mortality of 1:12000. Patients should also be informed of the risk of converting to laparotomy. Management Anovulation A normal follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) level excludes premature ovarian failure. For patients with secondary amenorrhoea and galactorrhoea, assay of prolactin level can be useful and they can be treated with dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine. When the prolactin level becomes normal, ovulation returns. In rare cases of primary hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) is an effective treatment. The most commonly used ovulation inducing agent is clomiphene which is an antioestrogen. The starting dose is 50mg per day for 5 days, usually starting on day 2 of the menstrual cycle. The dosage can be doubled if there is no response after 3 cycles. Dosage beyond 100mg has a detrimental effect on cervical mucus and endometrium. Cervical mucus becomes thickened and may impede the penetration of sperm. If ovulation occurs for 6-12 months and the couple still fails to conceive, other ways of ovulation induction should be considered. There is an increased risk of ovarian cancer associated with prolonged usage of clomiphene. It is safe when used for less than 12 cycles.3 Human menopausal gonadotrophins (HMG), purified or recombinant FSH and GnRH agonist may be used if clomiphene fails. HMG is derived from urine of postmenopausal women and is available in 75-unit ampoules containing both FSH and luteinising hormone (LH). It is given intramuscularly. Highly purified FSH can be administered subcutaneously by the patient herself. Recombinant FSH and LH are produced by transfecting human gonodotrophin genes into the hamster ovary cell lines. They have the advantage of having more purified gonadotrophins. Treatment with gonadotrophins starts on day 5 of menstrual cycle or day 7 if clomiphene is added from day 2 to day 6. Transvaginal ultrasound is used for monitoring of endometrial response and follicular growth. Ovulation is triggered with a single dose of human chorionic gonadotrophin if there is at least one but not more than 3 mature follicles. However, there is a significant risk of hyperstimulation and multiple pregnancies. Clomiphene has a multiple pregnancy rate of 11%, and that of gonadotrophins is around 20%. In patients with anovulatory subfertility associated with polycystic ovaries, ovulation induction can achieve a pregnancy rate as high as the natural rate of normal women appropriate for their age. However, the incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation and multiple pregnancies is higher. For these patients, laparoscopic ovarian diathermy alone or combined with postdiathermy antioestrogen treatment can be very effective in selected cases with fewer hyperstimulation and multiple pregnancies.4 Tubal factor In-vitro fertilisation (IVF) was originally developed for the treatment of tubal factor infertility. It is indicated for women with moderate to severe tubal disease, husbands with sperm dysfunction or unexplained infertility. If the female partner is over 35 years old, more aggressive treatment such as IVF should be started early. However, it is a stressful and time-consuming treatment. Each treatment cycle offers a single chance for ova retrieval, and multiple chance of pregnancy if more than two or three embryos are obtained and frozen. Nevertheless, the number of treatment cycles are often limited by financial considerations or the female partner's age. On the other hand, successful tubal surgery can provide permanent improvement, with the possibility of more than one pregnancy. Tubal reanastomosis for patients with tubal ligation achieve a pregnancy rate as high as 80% and thus should be recommended. Salpingostomy by reopening of the ostium of fallopian tube and reconstructing the fimbrial ends can be performed laparoscopically or by laparotomy. Cases with good prognosis are those with small hydrosalpinges which have thin walls and normal tubal mucosa. The frequency of ectopic pregnancy after tubal surgery may be as high as 5%. Patients should be warned and advised to have early diagnosis of pregnancy and confirmation by ultrasound of an intrauterine pregnancy. Large hydrosalpinges are associated with poor prognosis and it may affect the outcome of IVF, possibly due to the toxic effect of hydrosalpingeal fluid on the endometrial environment. Salpingectomy should be considered for these patients before they embark on IVF.5 Unexplained infertility Ten percent of the infertile population who fail to conceive after 2 years of unprotected coitus may yield normal results in a routine fertility work up. It is estimated that 60% of couples with unexplained infertility of less than 3 years duration will become pregnant within 3 years of expectant management. Secondary unexplained infertility has a better prognosis than primary. For the rest, controlled ovarian stimulation (OI) with intrauterine insemination of washed sperm (IUI), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) and IVF are all superior to no treatment.6 OI and IUI has a success rate of 40% after three cycles of treatment. The principle is to bring the selected highly motile sperms near to the two or three mature follicles at the time of ovulation to increase the chance of pregnancy. If this fails or if the female partner is more than 35 years of age, IVF should be considered. Most IVF centers do not perform GIFT, as it involves laparoscopy and does not provide information on fertilization when the woman does not conceive. Endometriosis The incidence of endomeriosis is 1-7% in the general population and with higher incidence in the subfertile group. The severity of pelvic endometriosis is classified according to the revised American Fertility Society scoring system. Severity of disease is the most important prognostic factor. The association between mild endometriosis and infertility is controversial. Mild endometriosis has a high spontaneous pregnancy rate with expectant treatment. On the other hand, women who are found to have mild endometriosis on diagnostic laparoscopy and have the visible endometriotic tissue ablated have a higher cumulative pregnancy rate than the control group. Therefore, it is recommended that mild endometriosis should be ablated at the time of laparoscopy.11 Medical suppression of endometriosis does not enhance fertility. Ovulation induction and IUI increases fecundity in patients with endometriosis and the results are comparable to IVF.7,8 For moderate to severe cases, surgical treatment is indicated for two purposes: to remove or destruct the endometriotic cyst wall and to ablate active endometriotic tissue, and to correct anatomical distortion induced by adhesions. Cumulative conception rate after surgical removal of deeply infiltrating endometriotic tissue is 60% in 12 months in tertiary centers.9 Most procedures can be accomplished laparoscopically. If pregnancy does not occur within 6-12 months, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination can be attempted. Medical therapy for moderate or severe endometriosis will not improve fertility but it does suppress disease progression and can be given while patients await IVF. Male factor infertility The cause and pathogenesis of most male infertility remain uncertain. The response to hormones or other treatment is often unsatisfactory. Male partners should be advised to refrain from smoking and alcohol, and from wearing tight jeans. Men with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism respond to endocrine treatment. Donor insemination of sperm can be considered if there is severe male factor infertility or the presence of genetic disorders. This service is available from the Family Planning Association. Mild male factor infertility such as slight decrease in sperm count can be treated with superovulation and intrauterine insemination. With IVF or GIFT, the fecundity can be 2.5 times higher.10 IVF requires at least 50,000 motile sperm whilst microscopic manipulation with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) only requires a few sperm from which one sperm is chosen and injected. Sperm retrieved surgically from either the epididymis or the testis are usually too scanty for either intrauterine insemination or conventional IVF, but can do well with ICSI. There is no evidence that babies born with this technique have any increased congenital abnormalities. However, there is a higher chance of chromosomal abnormalities and there is also concern whether male babies born following ICSI would also have infertility as their fathers. Conclusion With various treatments available, case selection is the most important step to improve the pregnancy rate and to reduce the financial burden, both to patients and to the health care system.

H F Tung, MBChB, MRCOG, FHKAM K M Chow, MBBS, MRCOG, FHKAM Consultant, Chief of Service, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Princess Margaret Hospital. Correspondence to: Dr H F Tung, Room 240, Tung Ying Building, 100 Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong. References

|

||