|

September 2001, Volume 23, No. 9

|

Discussion Paper

|

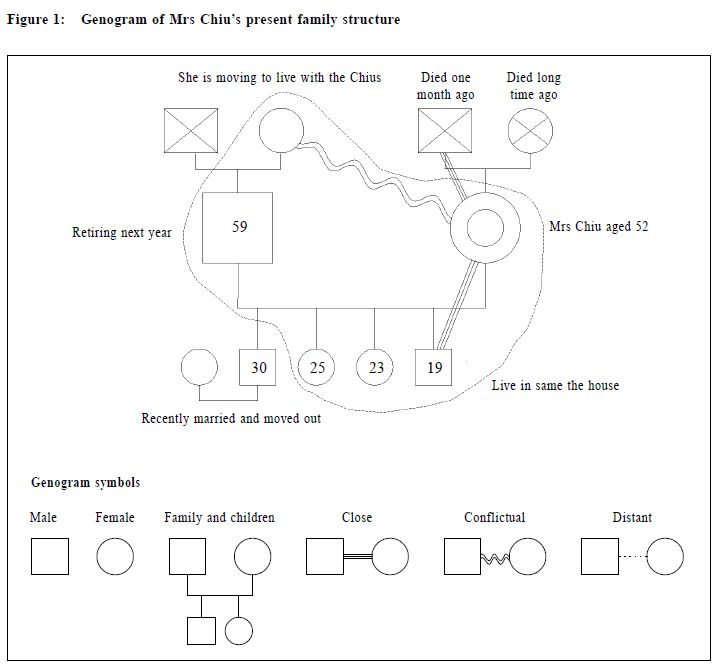

Functional disorders and their assessment in family practice – do we have time?N C L Yuen 阮中鎏 HK Pract 2001;23:401-404 Summary Family doctors see many patients in their daily practice who present with physical symptoms that are primarily of emotional or psychological (functional) origin with ill defined or no organic causes (somatoform disorders). It has been well documented, that this group of patients constitutes a significant proportion of visits to primary care clinics. Primary care doctors need to know how to recognise, assess and treat or when to refer such patients. Pertinent questions always raised include time constraints for dealing with these patients in busy primary care settings or that family physicians are not trained to do so. However, if the interviews are focused and structured, and with some training, there is no reason why primary care doctors cannot competently meet such demands. 摘要 家庭醫生常見到主訴軀體病徵的病人,但病因是 情緒或心理的原因(功能性)或是沒有明確的器質性 原因(軀體心理疾病)。這些病人在基層醫學中佔有 相當的比例。基層醫生需要知道如何確認、評估、治 療和何時轉介這類病人。工作時間緊迫和缺乏訓練是 基層醫生面對的兩大困難。通過集中有計劃的會診安 排加上足夠的訓練,基層醫生是有能力治療此類病人 的。 Introduction First of all I would like to quote a case from Professor Frede Olesen of Denmark who delivered a keynote address at one of the Plenary Sessions at the Vienna WONCA Conference in July 2000, entitled "Somatising Patients in General Practice – Can we Improve Diagnosis and Care?" The story is about a 30 years old female who has had pain in her chest near the breast from time to time for five years. Doctor A listens to her symptoms, examines the patient's muscles and breast. He explains that there does not appear to be anything seriously wrong. They discuss pros and cons of mammography and agree not to perform this for the time being. The rhythm of the consultation is good, the patient seems reassured and satisfied when she leaves the room, and the final diagnosis is muscular pain. However, Dr A did not notice three important sentences spoken by the patient during the consultation. Firstly, she said: "Sometimes it comes when I feel stressed", then "sometimes it comes when I wake up at night and think of all the work I have to do the next day" and later: "I wonder if it has anything to do with stress". However, both Dr A and the patient perceive the consultation as having gone well. Dr B, on the other hand, examines the patient in a way to make sure she feels understood and taken seriously, and to be sure that there is nothing physically wrong with her. At the same time he has a discussion with the patient about her work and her feelings of stress, and they discuss that stress may cause muscular pain. At the end of the consultation she feels reassured and has learned about mind-body relations. Now what is this about? Professor Olesen called it "body sensations that are turned into symptoms that are finally turned into a diagnosis". Dr A makes the diagnosis of muscular pain. What is the diagnosis made by Dr B? Dr B makes the diagnosis of somatising behaviour, that is, a functional or psychosomatic disorder. Definition and prevalence Functional disorders can be defined as physical disorders caused or aggravated by psychological factors. They can be viewed as responses made by an individual to stress. They can broadly be defined into two main categories: (A) Those that contribute to physiological or pathological changes (e.g. asthma, peptic ulcer, and irritable bowel syndrome); and (B) Those that give rise to physical symptoms in the absence of physical disease (somatisation) (e.g. headache, palpitation or muscular pains).1 More detailed description of somatoform disorders in terms of diagnostic classification and management can be found in the excellent Update Article by K Y Mak in the October 2000 Issue of "The Hong Kong Practitioner".2 However, many anxious patients do not meet strict criteria for diagnosis of anxiety or depressive disorders when they first present. They are often seen at early stages in the illness by primary care doctors who are in an excellent position to provide therapeutic intervention early on, before the symptoms become truly disabling.3 As family doctors, we see many patients who present with physical symptoms that are primarily of emotional or psychological origin with no organic cause.4,5 Studies have shown that 10-20% of primary care patients may have functional elements as opposed to biomedical problems as the main reason for their visits.6-8 Most if not all of our Chinese patients express their emotional problems through physical symptoms.9 Family rules may lead the family members to have great hesitation about revealing their family secrets to others, expressing anger or criticising their parents and siblings in front of others, as this reflects disloyalty, ingratitude, or disrespect towards them. Even if they have expressed and revealed their anger, there is usually a sense of guilt.10 A large percentage of these patients do not know that their symptoms could be related to emotional or stressful situations at home or at work. For many patients, the suggestion that their symptoms could be psychological implies that their symptoms were not "real" or that they were imagined. Since many primary care doctors have little training in dealing with emotional disorders, there is a tendency to treat the physical symptoms alone. And when the physical symptoms persist, patients wonder why the medications do not work, and will try to obtain treatment elsewhere, adding to the so called "doctor shopping" behaviour. How do we assess? We, as family doctors must realise that functional disorders are common problems that should be taken seriously. How do we do it? We should try to pay more attention to our consultation and diagnostic skills, putting more emphasis on psychosocial rather than on purely biomedical orientation. Next, we need to spend more time understanding the patient's family structure and function. Knowing how to use a genogram is a quick way of understanding family dynamics.11 In order to better understand a patient's personality, and the way he/she reacts and copes with stressful situations, the family doctor should try to learn more about his/her growing environment. The common concerns voiced by family doctors is either that we do not have the time or that we have insufficient training to deal with psychosocial problems. However, if the patient interview is more focused and structured, and with some training, the patients concerns can be alleviated. Let me show you a recent case history to demonstrate my point. Just about 3 weeks ago, Mrs Chiu, aged 52 years, came to see me after being referred by a friend. She complained of weakness in the legs, dizziness, shortness of breath, a tight feeling in the chest, poor appetite and she had not been sleeping well. She was a non-smoker, non-drinker, and had no history of allergies. She had a past history of duodenal ulcer, but was cured of this many years ago. Physical examination was normal. With regard to her family and social history, here is her story: The genogram illustrates the family story. (Figure 1)

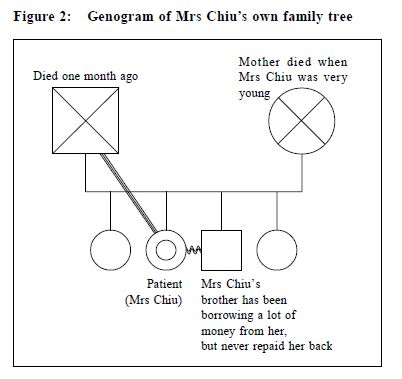

Mrs Chiu was worried about her mother-in-law coming to live with her family, she knew her mother-inlaw was a very difficult person to live with. She had four children. One son was married and had moved out, the second son and third daughter were working and were living at home. The youngest son had just started university this year. It was obvious that she was concerned with how she could live with her mother-inlaw. Here was a person with multiple, non-specific symptoms. She was anxious and looked depressed. As always, consultation with a patient with psychosocial problems takes a longer time than consultation with a patient with biomedical problems. She was assured that she had no serious diseases which she might be worried about, and that her discomfort was probably due to anxiety and stress. This ended the first consultation, which lasted for about 12 minutes, and she was given some mild anxiolytic. One week later, Mrs Chiu came back and told me that she had been feeling better but the feeling of weakness and tight feeling in the chest had not completely gone away. I decided to explore her own family further. During the interview, she suddenly burst into tears. She was the second daughter of four siblings (Figure 2).

Her mother had died many years ago when she was still young, but her father had died just one month ago. It had been a big loss for her as she was very attached to her father. She was very angry with her younger brother, who had borrowed money from her from time to time, but had failed to repay any of it in the last 10 years. As a result, her life savings were gone. Her younger son, who had just turned 19, now needed $43,000 per year for his university tuition fees. She was unable to help him since she had no money of her own and the family did not have enough money to support him. She was really in a bad situation. She felt frustrated, angry and helpless. After spending 10 minutes with her, I could understand her sad predicament, but as a family doctor, apart from lending a sympathetic ear and reassuring her that she did not have serious illness, what could one do? I suggested to her whether she had considered a university loan. She said she would talk to her son about it. I reassured her again that her symptoms were not due to any physical disease. Mrs Chiu apologised for her outburst of tears, however, she appeared relieved. Conclusion In dealing with functional disorders, first of all, we do not need that much time in every consultation. If it is a long case, we can always divide the time needed into different sessions. A key factor in time management is deciding early on what must be known today and what can wait until the next visit or the one after that. If it is a more complex and difficult case, then we should consider referring the case to a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. In regard to assessing a patient's family structure and function a genogram can help a doctor integrate a patent's family information into the medical problem-solving process. A genogram allows a doctor to obtain medical and psychosocial information from a patient easily and quickly and , as a result, to have a better understanding of the context of the presenting symptoms.12,13 A very good article published in the Canadian Family physician on "Genograms, Practical tools for family physician"11 is worth reading. Key messages

N C L Yuen, MBBS, MD, FRACGP, FHKAM(Fam Med)

Adjunct Professor, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr N C L Yuen, 22A Junction Rd , G/F, Kowloon City, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

|