|

August 2002, Volume 24, No. 8

|

Case Report

|

||||||

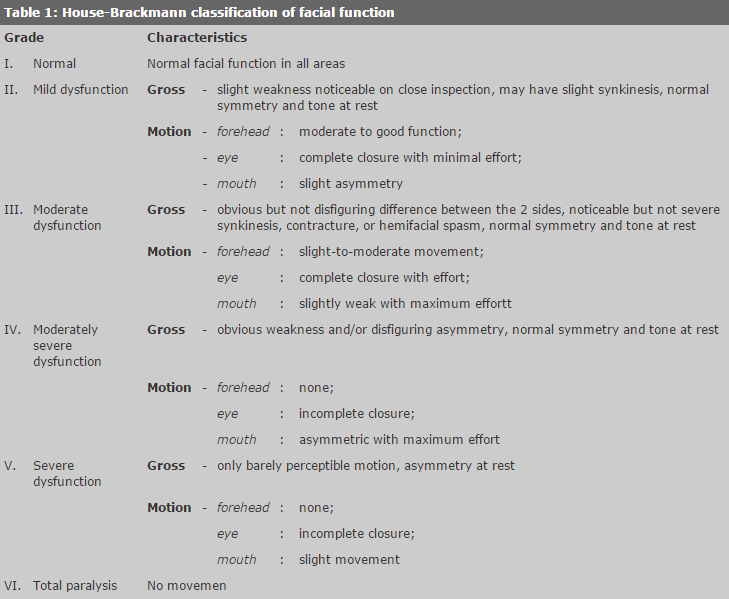

Neurological sequelae of acute otitis media in a six-month-old baby - facial nerve palsy: a case reportY L Cheuk 卓幼蓮, C K Chow 周振權, Y Hui 許由 HK Pract 2002;24:401-404 Summary Acute Otitis Media (AOM) is common among children. It almost always resolves completely with no sequelae. In unusual cases, however, bacterial resistance to antibiotics, disordered host immunity or anatomical deficits may lead to severe complications including facial nerve palsy. Prompt treatment by drainage and appropriate antibiotics is required for recovery from facial nerve palsy. 摘要 急性中耳炎常見於兒童,絕大多數經適當治療都 會痊癒。不過某些特殊情況下,例如:抗藥性病菌,自身免疫疾病和先天結構缺陷,可能出現包括面神經麻痺等嚴重的併發症。通過及時引流和適當的抗生素治療面神經麻痺可以康復。 Introduction Children often present with acute otitis media (AOM). Most infections are controlled and managed conservatively without severe sequelae. Complications can occur if there is bacterial resistance to the antibiotics, immature host immunity or a congenital predisposing factor such as dehiscence of the fallopian canal. Prompt recognition and treatment are necessary. Case report A six-month old baby girl presented with upper respiratory tract infection symptoms for one week followed by fever and purulent otorrhea from the left ear. Otoscopy showed pus in the left ear canal. She was given a course of oral antibiotics (Augmentin) and her fever gradually subsided. However, the purulent otorrhea from the left ear continued. She became less playful and showed a decreased response to the voice from the left side. When her fever returned on the ninth day after first presentation, she was noticed to have left facial weakness. An otorhinolaryngologist was consulted. Physical examination revealed House-Brackmann grade III (Table 1) left facial nerve palsy, i.e. mild drooping of the angle of the mouth but eyelid can be closed1 (Figure 1). Otoscopy showed a bulging left eardrum compatible with AOM. The mastoid did not seem to be tender. A left ear swab culture came back showing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, sensitive to Ceftazidime. Ofloxacin eardrops and intravenous Ceftazidime were started. An urgent CT scan of the temporal bone showed fluid and granulation in the left middle ear, with bony erosion into the mastoid cells. The CT scan also detected dehiscence of the fallopian canal (Figure 2), which is the bony canal containing the facial nerve. By this time, her facial weakness had deteriorated to House-Brackmann grade VI, i.e. paralysis of whole left side of her face. Emergency drainage of the mastoid infection was performed via a cortical mastoidectomy. Operative findings showed multiple perforations of the eardrum with pus and granulation in the middle ear and mastoid cavity. There was also a 5mm bony erosion of the mastoid cortex (Figure 2). Drainage of the pus was sufficient to control the inflammation and achieve decompression of the nerve. In order to avoid further damage to the nerve, the facial nerve was therefore not explored.

Post-operatively, she was given intravenous Dexamethasone 0.5mg q8h for three days in order to reduce the injury to the facial nerve due to inflammation. The course of antibiotics given intravenously was continued to completion. The facial weakness improved to House-Brackmann grade II on the sixth day after the operation, and recovered completely by the ten th day. Discussion

Research has shown that AOM accounts for 6.3% of all consultations for paediatric patients in private practice in Hong Kong.2 In the USA, there are 24.5 million consultations per year for children suspected of having AOM by paediatricians and family physicians3 and it is reported to be responsible for 8% of paediatric presentations in general practice in Australia.4 AOM occurs most often in children between the ages of 6 and 36 months. Almost three-quarters of all children experience at least one episode of AOM, and a third will have three or more episodes by the age of 3.3 Of all the pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for 30% to 40% of cases of AOM, followed by Haemophilus influenzae at 20% to 30%, and Moraxella catarrhalis at 22% to 27%. Respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus and influenza viruses are the other common causes.3 Pseudomonas aeruginosa was found in the culture taken from our patient. This unusual organism is more likely to be found in infants with poor host resistance. Its resistance to antibiotics explains the patient's poor response to oral Augmentin. Complications related to otitis media were common in the time prior to the discovery and use of antibiotics. They included otitic meningitis, brain abscess, mastoiditis, chronic otitis media, facial paralysis and hearing loss. Fortunately, these problems have become less common with advances in diagnosis and antibiotics. The complications our patient suffered were acute mastoiditis and facial palsy. Facial nerve palsy is an uncommon complication in AOM unless there is dehiscence of the fallopian canal. A study in Denmark, which examined retrospectively patients over a 17-year period, reported the incidence of facial nerve palsy during AOM to be 0.005%.5 Eight percent of patients with facial nerve paralysis have it as a result of suppurative otitis media.6 Direct extension of the inflammatory process to the fallopian canal via persistent dehiscence or direct invasion of the infectious organisms into the facial canal through the middle ear results in edema of the inflamed nerve within the fallopian canal. Venous return is cut off and the increasing pressure on the nerve leads to its dysfunction. The CT scan of the temporal bone of our patient showed a dehiscence of the fallopian canal. Poor host resistance, in infants can also play an important role in the development of facial nerve palsy from AOM.7 Eradication of the suppurative process is the most important goal in treating AOM with facial paralysis. Intravenous antibiotics are the treatment of choice, however, myringotomy and mastoid surgery might be necessary if the suppurative process does not respond to medical therapy. The results of prompt recognition and treatment are usually excellent, with complete resolution.5,6,8 In summary, if complications are to be avoided, it is important not to miss the diagnosis of AOM in children. Diagnosis may be difficult, however, as signs and symptoms of AOM in young children are often non-specific and subtle, particularly in infants. It is important, therefore to be vigilant for signs and symptoms such as neck stiffness, mastoid tenderness, facial asymmetry, etc, which indicate possible complications. Jensen and Lous9 reported that the diagnostic certainty of AOM was 67% in children under 2 and increased to 75% in older children. This is related to a good view of the eardrum and could be improved by cleaning the ear canal and more use of pneumatic otoscopy. Tympanometry is another very useful tool for identifying otitis media with effusion.

Y L Cheuk, MBBS(HK)

C K Chow, MBChB(CUHK), FRCS Ed(ORL), FHKAM(ORL) Consultant (ENT), Division of Otorhinolaryngology, Department of Surgery, University of Hong Kong Medical Centre, Queen Mary Hospital. Correspondence to: Dr C K Chow, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of Hong Kong Medical Centre, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong. References

|

|||||||