|

December 2002, Volume 24, No. 12

|

Case Report

|

|

A patient requiring three hours of cardio-pulmonary resuscitationH H Sze 施漢豪,S C Siu 蕭成忠,K P Leung 梁機培 HK Pract 2002;24:608-610 Summary Cardiac arrest is frequently encountered in our daily practice. We report a case of refractory ventricular fibrillation secondary to hyperkalaemia in an elderly man. The patient was known to have ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, and mild renal impairment with polypharmacy. He presented with sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation was carried out immediately. He responded after normalisation of the high serum potassium level. 摘要 醫院裡我們常遇到心臟驟停的情況。本文報告一位老翁由於血鉀過高引起心室纖維顫成年人病例。病者原有冠心病、充血性心臟衰竭和輕度腎功能損害,同時服用種藥物。因突發心臟驟停和心室纖顫,需進行急救,當血鉀水平恢復正常後病人獲救。 Introduction Hyperkalaemia is a potentially life-threatening condition that can be difficult to diagnose because of a paucity of distinctive signs and symptoms. Physicians must have a high index of suspicion as hyperkalaemia can lead to sudden death from cardiac arrhythmias. Any suggestion of hyperkalaemia requires an immediate electrocardiogram (ECG) to ascertain whether electrocardiographic signs of electrolyte imbalance are present. Case report

A 72 years old gentleman was diagnosed with ischaemic heart disease, congestive

heart failure, mild renal impairment and gout 5 years ago. Percutaneous transluminal

cardioangioplasty was done for his triple vessels disease 2 years later. In a cardiac

rehabilitation programme, he received comprehensive education, and exercised regularly

under close supervision. His medication included digoxin 62.5mcg daily, furosemide

80mg daily, isosorbide mononitrate 60mg daily, atorvastatin 10mg daily, aspirin

80mg daily, and perindopril 8mg daily. Since then, he had been admitted to hospital

six times for congestive heart failure secondary to ischaemic heart disease. The

latest echocardiography one year ago showed a dilated left ventricle with markedly

impaired function (ejection fraction of <10%), mild mitral regurgitation and

moderate tricuspid regurgitation compatible with ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy.

Spironolactone 25mg daily and carvedilol 3.125mg daily were added to optimise the

regime. Renal function was monitored (sodium 135mmol/L, potassium 4.4mmol/L, urea

13.7mmol/L, creatinine 141

Earlier this year, during walking exercise under supervision, he collapsed suddenly.

He became unconscious with no detectable pulse and blood pressure. ECG showed ventricular

fibrillation (VF). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was started immediately.

Defibrillation and antiarrhythmic drugs were given repeatedly to no avail, VF persisted.

Meanwhile, he was put on mechanical ventilation and received continuous external

cardiac massage. Results of laboratory tests showed sodium 132mmol/L, potassium

7.4mmol/L, urea 23.2mmol/L and creatinine 217

After resuscitation, he regained consciousness and obeyed commands. Potassium level

was around 6.5mmol/L. A further 40 units of soluble insulin infusion was given to

bring the potassium down to normal level. On the next day, mechanical ventilation

was stopped successfully. All his medications were resumed except perindopril and

spironolactone in view of their association with hyperkalaemia. His general condition

improved and his renal function was stable: sodium 141mmol/L, potassium 4.5mmol/L,

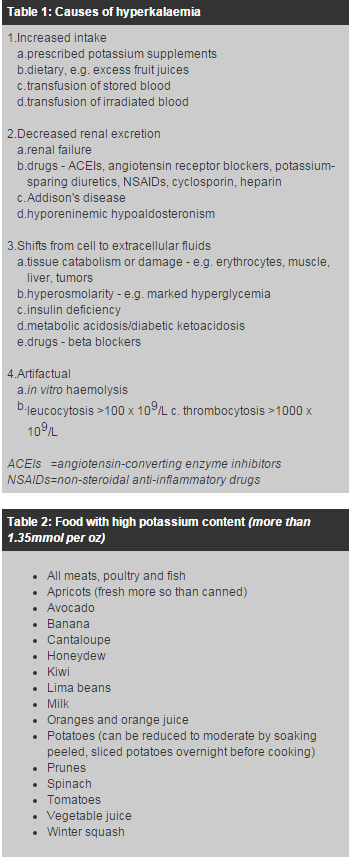

urea 11.2mmol/L and creatinine 102 The patient suffered from refractory VF, which was probably caused by hyperkalaemia. He had mild chronic renal failure, on perindopril and spironolactone, all of which are known to increase the risk of hyperkalaemia. On detailed review of his diet, he disclosed that he took a lot of fruits, about 10 oranges and 5 bananas, every day. Oranges and bananas have high potassium content; one medium orange contains 6.5mmol, one medium banana contains 8mmol.1 The large amount of fruit intake was likely to contribute to the occurrence of hyperkalaemia in this patient who was already at high risk. Discussion There are many causes of hyperkalaemia (Table 1).2 The usual daily dietary intake of potassium varies between 80 and 150mmol depending on the amount of fruit and vegetable. Foods with high potassium content are shown in Table 2. Treatment of hyperkalaemia depends on the urgency of the clinical status, potassium level, cardiac symptomatology, and the rate at which the hyperkalaemia evolved. Emergency treatment of hyperkalaemia consists of two phases. The first is to rapidly counteract the effects of hyperkalaemia, and to induce an intracellular shift of the ion, these effects are transient. The second phase is the removal of potassium from the body. Diuresis, ion exchange resin and dialysis are definitive means of eliminating potassium from the body. Concerning the ion exchange resin, more rapid effect is achieved with rectal rather than with oral administration. Each enema should be retained for 30 minutes and may decrease serum potassium level by 0.5 - 2mEq/L.3 Resonium C removes potassium from the body by exchanging it within the gut for calcium. This action occurs in the large intestine, which excretes potassium to a greater degree than does the small intestine. Resin is not selective for potassium. The efficacy of potassium exchange is unpredictable and variable.

Schepkens Hans et al. suggested that a combination of angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors (ACEIs) and spironolactone should be used with caution and monitored

closely in patients with renal insufficiency, diabetes, older age, worsening heart

failure, at risk for dehydration, and in combination with other medications that

may cause hyperkalaemia.4-6 Patients with creatinine levels of 120 to

150

Our experience with this patient emphasises the importance of obtaining a detailed history in patients who have serious hyperkalaemia that is not readily attributable to acute renal failure, or other known predisposing factors. Patients who are predisposed to hyperkalaemia should avoid eating excess amount of fruit, particularly if they have impaired renal function or are taking medications with potassium sparing effects such as ACEIs and angiotensin II antagonists. Starting CPR promptly in case of cardiac arrest has been proven to be effective in improving the outcome of prolonged VF.9 It is also important to monitor the renal function closely if they are taking ACEIs, potassium sparing diuretics and/or angiotensin II antagonists.

H H Sze, MBBS(HK)

S C Siu, MBBS(HK), MRCP(UK), FHKCP, FHKAM(Med) Chief of Service, Department of Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tung Wah Eastern Hospital. Correspondence to: Dr H H Sze, , Department of Medicine & Rehabilitation, Tung Wah Eastern Hospital, 19 Eastern Hospital Road, Hong Kong. References

|

||