|

December 2002, Volume 24, No. 12

|

Original Article

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Study on behaviour change after dietary education intervention in elderly people with hypercholesterolaemiaR S Y Lee 李兆妍,R H Y Li 李曉陽,K S Ho 何健生 HK Pract2002;24:583-593 Summary Objective: To evaluate the awareness, knowledge, stages of behaviour change using the Transtheoretical model, significance of different perceived barriers to behaviour change and the factors affecting behaviour change in elderly people with total cholesterol ?5.2mmol/l three months after dietary education intervention. Design: Prospective cross-sectional survey by questionnaire. Subjects: 256 elderly patients from an elderly health centre. Main outcome measures: The awareness, knowledge of hypercholesterolaemia, stages of behaviour change, and the perceived barriers to behaviour change were evaluated three months after dietary education intervention. Results: Only 46.1% reported behaviour change although over 98% were found to have good awareness, knowledge and intention to change. The major perceived barriers to change were lack of self-control, lack of control over food preparation at home, reluctance to affect family members, and eating out. No significant association was detected between behaviour change and demographic factors, lifestyle or pre-existing health status. Conclusion: Assessing the stages of behaviour change with stage-matched interventions may be more effective in changing behaviour.Keywords: Behaviour change, diet, hyperchole-sterolemia 摘要 目的: 調查總膽固醇相等或高於5.2mmol/l 的長者接受飲食建議三個月後,關於膽固醇的知識、警覺性、行為轉變的階段、意識到的主要障礙以及其影響因素。 設計: 以問卷作前瞻性橫切面式調查。 對象: 同一長者健康中心的 256位長者。 測量內容: 評估接受飲食建議三個月後,受訪者的警覺性、關於膽固醇的知識、行為轉變的階段和主要意識到的障礙。 結果: 雖然有超過98%的受訪者有良好的警覺性、知識以及改變的意向,但只有46.1%有行為上的轉變。意識到的主要障礙包括缺乏自制力、難以控制家中煮食、不願影響家人和外出進餐。行為轉變與人口統計因素,生活方式和原有健康狀況沒有明顯的聯繫。 結論: 評估病人所處行為轉變的不同階段,並且提供相應的治療,可能更有利病人的行為改變。 主要詞彙: 行為轉變,節食,高膽固醇血症 Introduction Ischaemic heart disease is one of the commonest chronic illnesses in Hong Kong. Local studies showed a prevalence of 11.2%1 to 18% in the elderly,2 and elevated serum cholesterol has been found to be a major modifiable risk factor for arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease.3,4Therapies for hypercholesterolaemia include drug treatment and adopting a healthy lifestyle: eating a healthy diet, getting regular exercise and quitting smoking.5 Dietary intervention has been found to be effective in the care of patients with hyperlipidaemia,6 and it is now the first approach to control blood cholesterol.7 The best trial data regarding the efficacy of diet came from the Lyon Diet and Heart Study.8 Other studies have also suggested that educational interventions are effective in decreasing serum cholesterol.9,10 The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of behaviour change has been presented as an integrated and comprehensive model of behaviour change.11,12 Original work based on the TTM was related to smoking cessation. It has been applied successfully to promote change in diet behaviour.13,14 The TTM is a general explanatory model of behaviour change.11 It is based on the premise that people move through a series of stages in their attempt to change a behaviour. Assessing the stage of change a patient is at and then tailoring behaviour change interventions to that stage has received support.15 Interventions that are mismatched to stage have been found to be less effective than stage-matched interventions.16 For individuals in the stage of precontemplation who do not intend to change their behaviour, the goal is to increase awareness of the need to change. For individuals in the stage of contemplation and preparation, the goal is to increase their motivation and self-confidence in their ability to change, and to negotiate a plan to change. For people in the action stage, the goal is to reaffirm commitment. For those in the maintenance stage, the goal is to encourage active problem solving to prevent relapse.17

Elderly Health Services (EHS) was established in 1998 to provide comprehensive primary

health services to elderly people in Hong Kong. All attendants of the elderly health

centres (EHCs) have their total cholesterol checked. Dietary advice and explanation

of the risk of hypercholesterolaemia on health by nurses is provided to all those

with total cholesterol

Objectives Hypercholesterolaemia is common and a major risk factor for ischaemic heart disease, which is one of the commonest chronic illnesses and leading causes of death in the elderly in Hong Kong. Dietary educational intervention is at present considered to be the first approach in its management. Understanding the barriers to behaviour change in the elderly who intend to change but have not done so may provide insight into the future direction of health promotion programmes in our services.

The study aims at assessing elderly patients with total cholesterol level

Methods Study design This is a survey using questionnaire (Appendix) to explore:

Target population

The target population is elderly patients at an EHC, aged 65 or over with total

cholesterol level

Pilot study

A pilot survey by questionnaire similar to that suggested by Burbank et al17

was conducted by face-to-face interview on 30 elderly patients with total cholesterol

level

Sampling study population

In an EHC, there are around 120 patients found to have total cholesterol

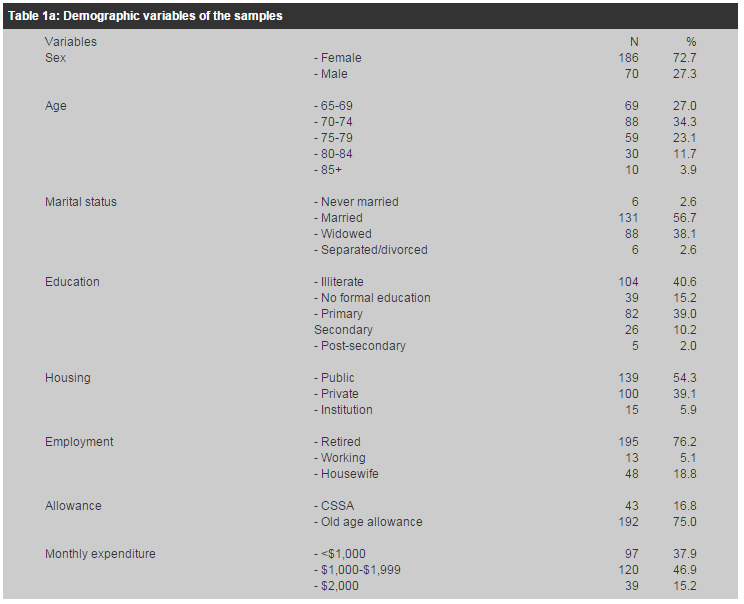

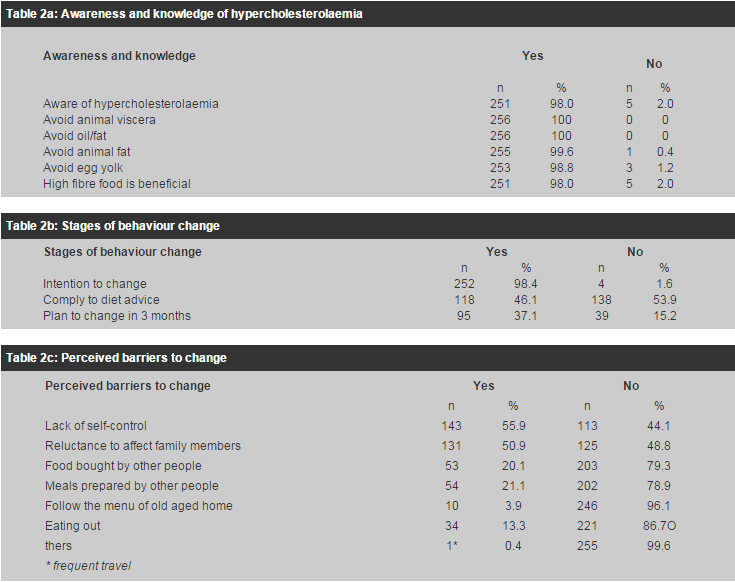

Exclusion criterion Elderly with severe hearing loss that could not be corrected by hearing aid were excluded from the study. Data collection Data were collected using questionnaire (Appendix) by face-to-face interview for all those who attended the follow-up from August to October 2001. Verbal consents were obtained prior to data collection. Statistical analysis Data were entered into Epi-Info ver 6 (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA), and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for windows ver 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, III). Descriptive results were presented as percentages. Statistical analysis was started with univariate analysis. Association between potential risk factors and cholesterol diet non-compliance was determined by the chi-square test of association. Attributable risk was used to determine the fraction contributing to the cholesterol diet non-compliance. The OR of cholesterol diet non-compliance was estimated by the logistic regression method. Multivariate analysis was then repeated using multiple logistic regression with a backward stepwise procedure. The cut-off point of entry of multiple logistic regression was fixed at 0.05 and the cut-of point of exclusion at 0.10. A two-sided 5% level of significance is considered significant for all statistical tests; exact probability values were reported down to p<0.001. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were provided as appropriate. Results Consecutive samples of 256 elderly were recruited from August to October 2001. Their demography and pre-existing health status are shown in Table 1. Their awareness and knowledge of hypercholesterolaemia, stages of behaviour change and perceived barriers to behaviour change are shown in Table 2a-c respectively. There were 118 (46.1%) elderly in the action stage, four (1.6%) in the precontemplation stage, ninety-five (37.1%) in the preparation stage and 39 (15.2%) in the contemplation stage.

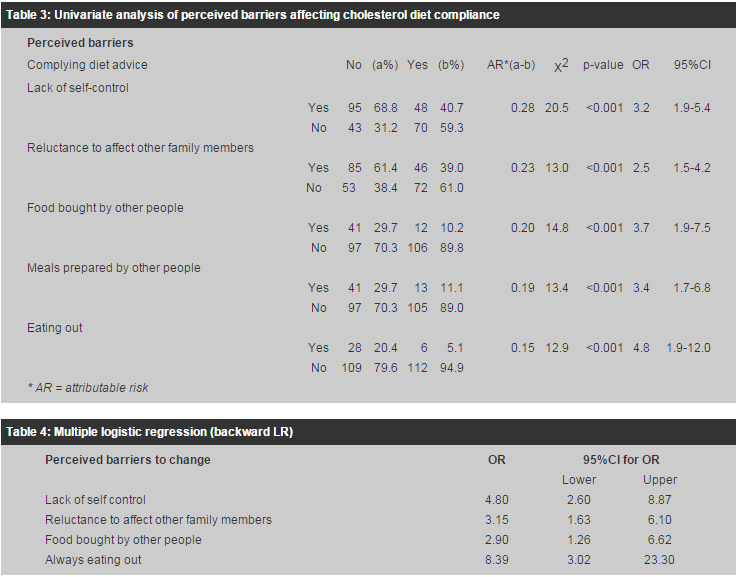

Univariate analysis of perceived barriers affecting diet compliance was performed. (Table 3) The most encountered perceived barriers were lack of self-control (AR=0.28), reluctance to affect other family members (AR=0.23), and food bought or prepared by other people (AR=0.20, 0.19), followed by eating out (AR=0.15). After adjusted for each factor by using multiple logistic regression, eating out is the most important perceived barrier to diet compliance (OR=8.39; 95%CI 3.02-23.30). This was followed by lack of self-control (OR=4.80, 95%CI 2.60-8.87), food bought by other people (OR=2.90, 95%CI 1.26-6.62), and reluctance to affect other family members (OR=2.90, 95%CI 1.63-6.10). Preparation of food by other people was excluded from the model after adjusting the other factors, probably due to its similarity to food bought by others. As all residents of old aged homes follow the menu of the old aged home, this would not be interpreted as a perceived barrier to change.

Univariate analysis for factors affecting diet compliance was performed. (Table 5) Application of the chi-square test revealed no significant association between behaviour change and demographic factors, lifestyle or pre-existing health status. However, the number of people with previous cerebrovascular accident was too small for interpretation by the test. Among the 41 elders taking a lipid lowering drug, 29 (71.0%) of them complied with the diet advice while among the 215 requiring no lipid lowering drug, only 89 (41.4%) complied. There was a significantly higher proportion of people complying with the diet advice in the group taking drug than those without it (OR=0.29, 95% CI 0.14-0.60, c2 test p=0.001).

Discussion It was found that most (98%) of the study population were aware of their hypercholesterolaemia. Their knowledge about diet was good, with almost all of them knowing what foods to avoid and that high fibre food was beneficial. Almost all patients (99.6%) received health education. This may have delivered good knowledge but was not very effective in changing behaviour. 252 patients (98.4%) intended to comply with the health advice but only 46.1% of them were in the action stage of behaviour change. 37.1% and 15.2% were found to be in the preparation and contemplation stage of behaviour change respectively. Only 4 (1.6%) had no intention of changing. These findings are compatible with the finding that traditional methods used to change health behaviours focus primarily on education. However, even after the best education, clients often make no change or practice the healthy new behaviour for only a short time before reverting back to their previous unhealthy patterns.17 Assessing individuals' stages of change and then tailoring behaviour change interventions to their stage of change has received support.15 Matching interventions to the variables of the TTM has been found to be effective in behaviour change.15 Interventions that are mismatched to stage have been found to be less effective than stage-matched interventions.16 For individuals in the stage of precontemplation who do not intend to change their behaviour, the goal is to increase their awareness of the need to change. For individuals in the stage of contemplation and preparation, the goal is to increase their motivation and self-confidence in their ability to change, and to negotiate a plan to change. The majority (52.2%) of our study population was in these stages and understanding their perceived barriers to change is therefore important to formulating a plan to change. The most frequently encountered perceived barriers were lack of self-control and reluctance to affect other family members, followed by food bought and prepared by other people. However, eating out has been found to be the most significant barrier, followed by lack of self-control, lack of control at home due to food preparation by other people, and reluctance to affect family members. Tailoring future health education activities in this direction may improve compliance. For people in the action stage (46.8%), the goal is to reaffirm their commitment. No significant relationship was detected between compliance and demographic factors, lifestyle or pre-existing health status except significantly more elderly on lipid-lowering drug complied with the diet advice. This group usually has higher blood cholesterol level and more risk factors. It is therefore not surprising to find them more ready for change and complying better. Limitations Consecutive samples of 256 patients were recruited over a 10-week period from August 2001 to October 2001. This is non-random sampling assuming that there is no seasonal variation. Furthermore, all interviews were carried out by the doctor. Patients may be reluctant to admit to their doctor that they have no intention of changing, and this may cause interviewer bias. Our target population was members of an elderly health centre where enrolment is voluntary. Our population had a higher female to male ratio (2.7), was older and was less literate and less economically active than the general population.18 78.4% of our members have one or more chronic illnesses. The prevalence of chronic diseases, hypertension and diabetes in our population was higher compared with some other local studies.19 As a result, the study population is a biased population compared to the general population. Data from this study may not be applicable to the general population. This study has evaluated only the gap between knowledge and behaviour change; whether compliance to dietary advice results in significant change in cholesterol level will need to be evaluated by further study. Conclusion Almost all of the study population was found to have good awareness of their hypercholesterolaemia, good knowledge about diet and good intentions of complying. Only 46.1%, however, reported behaviour change. 70.9% of those not complying reported intention of changing. 70.9% of those not complying reported intention of changing within 3 months. Their major perceived barriers were eating out, lack of self-control, lack of control over food at home and reluctance to affect family members. The goal for this group is to increase their motivation and self-confidence in their ability to change, and to negotiate a plan to change. Strategies targeted at eating out may include promoting healthy menus in restaurants, pamphlets on fat content of common restaurant food items, and substituting other social activities for eating out. Incorporating psychologist input into health education programmes may improve motivation and self-control. Encouraging family members to participate in health education activities, and empowering the elderly as health ambassadors of healthy diet in their families may also serve to prevent morbidity in the next generation. Almost half of the study population has already effected behaviour change. Continuous support to reaffirm commitment is necessary.Time available for educational intervention is usually limited, making it effective and efficient is important. Assessing the stage of change the patient is at and then tailoring behaviour change interventions to that stage has received support.15 Stage-matched interventions has been found to be effective in behaviour change.15 Burbank et al suggested using a simple questionnaire for the assessment of stages of change by four questions.17 Future health education may need to incorporate exploration of the atient's stage of behaviour change and targeting their perceived barriers to change.

R S Y Lee, MBBS(HK), FHKAM(Family Medicine), Dip Derm(London),

MPH(CUHK)

R H Y Li, MPhil, MSc Consultant Family Medicine, Elderly Health Services, Department of Health. Correspondence to: Dr R S Y Lee, , Aberdeen Elderly Health Centre, 10 Reservoir Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||