Management of advanced breast cancer - a multidisciplinary approach

K L Cheung 張國良, S Y Chan 陳恩達, A J Evans, L Winterbottom, J F R Robertson

HK Pract 2002;24:114-131

Summary

Despite improvement in screening and early diagnosis, breast cancer still presents or recurs in an advanced state (either locoregionally or with distant metastases) in a significant proportion of women. Advanced breast cancer is heterogeneous and requires a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis, treatment and long-term care. The surgeon, clinical/medical oncologist, radiologist and breast care nurse, all with adequate training and interest in advanced breast cancer, form the core personnel in the multidisciplinary team. Rational use of different modalities of therapy (e.g. surgery, endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, palliative treatments) is required to improve survival and quality of life.

摘要

雖然乳癌的篩選和早期診斷方法已有所改進,但 仍有相當比例的病人罹患原發或復發性晚期乳癌(局部或遠處轉移)。晚期乳癌是異質性的,它需要多部門合作診斷、治療及長期護理。訓練有素和集中研究晚期乳癌的外科醫生、臨床腫瘤科醫生、放射科醫生及乳房護理科護士是多部門護理團隊的主要成員。理性地運用不同的療法,例如:外科手術、內分泌治療、化學治療、放射治療及紓緩治療,可改善患者的生存機會及生活質素。

Introduction

The management of early primary breast cancer is more clearly defined1,2 than that of advanced breast cancer in the form of either locally advanced primary disease or metastatic disease. Due to the heterogenicity of the disease and the complexity of the clinical presentation, advanced breast cancer requires to be managed in a multidisciplinary fashion. The principles of management of locally advanced primary breast cancer (LAPC) and metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are discussed with particular reference to the multidisciplinary approach adopted by the Nottingham Breast Unit which is at present one of the largest, single, specialist, breast units in England and runs a through-and-through breast cancer service from screening, primary disease treatment to advanced disease treatment including palliative care.

Locally advanced primary breast cancer

Locally advanced primary breast cancer is defined either by size (>5cm) or by the presence of certain clinical features such as skin ulceration, chest wall fixation, peau d'Orange, fixed axillary node and/or lymphoedema, which are known as Haggenson's criteria.3 Prior to the era of systemic therapy, survival was poor after local treatment (surgery or radiotherapy) only. Many patients with LAPC die from metastatic disease despite aggressive surgery, although some patients have more indolent tumour and survive much longer. Locally advanced primary breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with differing behaviours and no single therapeutic approach is optimal for all patients.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually obvious although occasionally tumours of >5cm (usually in women with large breasts) are diagnosed through mammographic screening programmes. Histological diagnosis with needle core biopsy has the advantage of obtaining useful information (e.g. oestrogen receptor (ER) status) which may be used to guide treatment. In contrast to early primary breast cancer where metastatic work-up is often not cost effective, investigations to exclude distant metastases are required for patients presenting with LAPC since the chance of distant metastases increases with the size of the primary tumour and the diagnosis of metastatic disease usually saves the patient from undergoing surgery unless this is necessary for local control. These tests should at least include full blood count, serum tumour markers, liver function tests and serum calcium, chest radiograph and pelvis x-ray. Bone scan and liver ultrasound examination should be carried out if clinical features or liver function tests suggest the possibility of metastases.

Treatment

As noted above the survival of patients with LAPC has improved with the introduction of systemic therapies. There is a view at present among some clinicians that neoadjuvant (given before surgery) systemic therapy should be standard treatment. However in LAPC neoadjuvant systemic therapy has not been shown to be superior to standard therapy, i.e. primary locoregional treatment (surgery and radiotherapy) followed by adjuvant systemic therapy. Indeed the combination treatment approach using neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, radiotherapy with or without further chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy is popular and most recent clinical trials on the treatment of LAPC have involved comparison of different regimes of combination. Randomised trials which directly compare different therapeutic approaches for LAPC are sparse and two such trials have been carried out in Nottingham. The first study initiated in the early 1980s was a randomised, cross-over trial which compared initial treatment of LAPC with radiotherapy (i.e. a local treatment) versus tamoxifen (i.e. a systemic therapy).4 Radiotherapy was selected as the local treatment because it was widely regarded as the standard treatment at that time. It was also an attractive choice because of its non-operative nature and its high initial response rate (approximately 70%). However many of the responses to radiotherapy are short lived. The high rate of distant recurrence after radiotherapy (or mastectomy) indicates that many of these patients have occult metastases at presentation. With its excellent side-effect profile it was possible to view tamoxifen as a 'minimal' therapy. However tamoxifen was seen as a systemic therapy which might make a significant impact on not only the control of the primary tumour but also distant disease. Patients whose disease had progressed during the initial treatment (either radiotherapy or tamoxifen) were changed to the other treatment. No difference was seen in the two groups in terms of the rates of local failure, metastases and survival. The median time to progression of the second treatment was about two years which was comparable to that seen in another study of LAPC when both treatments were given initially in combination.5 It appeared that similar control of LAPC both locally and systemically could be achieved by giving a local treatment (i.e. radiotherapy) and a systemic treatment (i.e. tamoxifen) in a sequential manner. Nevertheless the survival figures (as well as the local and distant control results) were poor for both treatment groups, in line with previous studies and reports of LAPC. This prompted the commencement of the second randomised trial for LAPC patients in Nottingham in which a more aggressive approach was adopted (so called 'maximal' arm) and compared to tamoxifen ('minimal' arm). Patients were randomised, regardless of ER status, into two arms which compared initial endocrine therapy versus combination therapy using neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Patey mastectomy (mastectomy with full axillary clearance), postoperative radiotherapy and adjuvant endocrine therapy. Patients who had been randomised to receive initial endocrine therapy had their treatment changed as appropriate at the time of disease progression. The results of the trial were first published at a median follow up at 30 months showing no significant difference in the two treatment groups in terms of uncontrollable locoregional disease, rate of metastases and survival.6 A recent update at 52 months again confirmed the same findings.7 Treatment of LAPC using a sequential approach appears to be a reasonable alternative to the combination approach. Initial treatment with endocrine therapy produces superior results in cases of ER positive tumours compared to ER negative tumours.

To date neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not been shown to produce a survival benefit when compared with chemotherapy given post-operatively.8,9 It has the potential to downstage LAPC so that inoperable tumours can become operable and breast conservation is feasible in those patients who would otherwise require mastectomy. However it must be borne in mind that long-term follow-up has shown a higher local recurrence rate after breast conservation following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients whose tumour had been unsuitable for such surgery.8,9 On the other hand, endocrine therapy has the advantage over chemotherapy in having less side effects and in that it can be continued perioperatively. The role of preoperative endocrine therapy especially using the new agents such as the pure anti-oestrogens (e.g. fulvestrant (FaslodexTM, AstraZeneca)) and the third generation aromatase inhibitors (e.g. anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane) seems promising and is the focus of ongoing research.10

At present in Nottingham patients with ER negative LAPC who are deemed fit for multimodality therapy undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy (using 5-fluorouracil, adriamycin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) regime), Patey mastectomy followed by radiotherapy to the mastectomy flap. Patients with ER positive tumours receive either initial endocrine therapy with subsequent treatment change as appropriate at disease progression or combination treatment (surgery and radiotherapy) followed by adjuvant endocrine therapy if they wish the primary tumour to be excised. Chemotherapy is given depending on the patients' 'biological' age and the nature of the tumour (i.e. fast growing versus indolent tumour which the patient may have been aware of for many months or even years). Postmenopausal patients receive tamoxifen as standard endocrine therapy while premenopausal patients receive goserelin in addition to tamoxifen.

Patey mastectomy is the standard operation for patients with LAPC undergoing surgery although very occasionally radical mastectomy is required when the tumour involves the pectoralis major muscle. Sometimes resection of an area of chest wall is necessary. If the area of chest wall to be resected is substantial a thoracic surgeon is involved. Patients with stage IIa and some with stage III tumours who wish to discuss breast reconstruction are seen at a joint reconstruction clinic involving a breast surgeon and a plastic surgeon. Immediate reconstruction (using implant and/or autogenous tissue transfer) is carried out at the time of Patey mastectomy. Patients with T4 lesions are not offered breast reconstruction.

Metastatic breast cancer

The median survival of patients with symptomatic MBC is between 2-3 years and virtually all patients will eventually die from the disease. Maximising the quality of life with palliation of symptoms is the primary objective of management of MBC. Prolongation of survival is seen in patients in whom a response to systemic therapy can be achieved.

Diagnosis and staging

Information on the nature of the primary cancer (e.g. ER status, histological grade) is important to guide therapeutic decision making and this can usually be obtained from the histology report at the time of operation for the primary cancer. In cases when the first presentation is of MBC a needle core biopsy of the breast tumour is necessary to establish both the diagnosis of a breast primary and other information as required (e.g. invasive nature, ER status).

Accurate staging of metastatic disease is important as extensive lung or liver disease may indicate the need for chemotherapy even in patients with ER positive tumours.

Depending on the index of suspicion, a variety of investigations are carried out for possible MBC which presents either as the first presentation of breast cancer or as relapse after treatment of primary breast cancer. Full metastatic work-up includes blood tests (full blood count, liver function tests, serum calcium, tumour markers (e.g. CA15.3 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)), chest radiograph, bone scan (plus x-ray of hot spots) and liver ultrasound examination. Further tests may be required in certain circumstances. For example, a CT scan might reveal multiple pleural nodules in case of small pleural effusion seen on a plain chest radiograph. A high resolution CT scan can also help confirm lymphangitis carcinomatosa in doubtful cases. An MRI scan is indicated to investigate severe bone pain (e.g. in the spine) despite normal plain radiographs and bone scan. Lumbar puncture is indicated for suspected meningeal metastases when CT scan of the brain is not conclusive. Bone marrow biopsy may be indicated in a patient who is anaemic or even pancytopenic with negative imaging, although with the introduction of MRI this is less common. Bone biopsy to confirm the nature of a solitary bone lesion is still a valuable test. With the help of serum tumour markers (CA15.3 and/or CEA are elevated in between 70-90% of MBC) as a complementary tool,11 it is nowadays less necessary to resort to invasive procedures (e.g. bone biopsy, liver biopsy) to confirm a diagnosis of MBC.

Treatment

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapy in the form of either cytotoxic therapy or endocrine therapy is the mainstay of treatment for MBC. Where possible we prefer to try endocrine therapies until the tumour becomes hormone insensitive and then move to chemotherapy. However there are a group of patients with MBC where chemotherapy is the initial treatment of choice. The choice between chemotherapy and endocrine therapy depends on factors such as the ER status, the aggressiveness of the tumour, site and presentation of metastases, the likelihood of response and fitness of the patient to a particular therapy (Table 1). Generally speaking endocrine therapy works slower but once a response is induced, it can be sustained for a longer period. The best survival in MBC is achieved in a patient who has responded to endocrine therapy. Chemotherapy on the other hand induces responses more rapidly, but the duration of response is shorter than that with endocrine therapy. Obviously the group requiring chemotherapy has more aggressive disease. Thus typically chemotherapy has been used as a first line treatment in patients with immediately life-threatening disease especially if the tumour is ER negative. With the introduction of third generation selective aromatase inhibitors (e.g. anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane) and pure anti-oestrogens (e.g. FaslodexTM) the time to response in ER positive tumours seems to be shorter.

| Table 1: Endocrine therapy versus chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer |

|

Endocrine therapy |

Chemotherapy |

| Action |

Slow |

Rapid |

| Response |

Sustained |

Short-lived |

| Survival benefit |

Large |

Small |

| Side effects |

Less |

More |

| ER |

+ |

- |

| Sites |

Soft tissue, bone |

Viscera |

|

|

(a)

|

Cytotoxic therapy

The chemotherapy given on the development of MBC is dependent on whether the patient has received adjuvant chemotherapy and if so, the regime given. The conventional strategy is to start with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) and then with an anthracycline-containing regime. However there is an alternative view that there is no 'standard' first line chemotherapy regime12 and some oncologists tend to use an anthracycline-containing regime as a first line therapy for MBC especially if the patient has immediately life-threatening visceral disease.

Newer drugs have recently become available. Taxanes (including taxol and docetaxel) and vinorelbine act on the mitotic spindles and are generally used after an anthracycline-containing regime has failed. In some centres taxanes are used as first line therapy (e.g. in combination with doxorubicin).13,14 Recent data have suggested that doxorubicin and paclitaxel are not totally cross-resistant, which support further investigations of their use, either in combination or in sequence as single agents.15 Continuous 5-fluorouracil infusion could be useful after failing all other forms of chemotherapy and the oral fluorouracil derivative, capecitabine, has been shown to be effective in patients in whom both taxanes and doxorubicin have failed.16

In patients with tumour which overexpresses the oncoprotein c-erbB2 (HER2/neu), the humanised c-erbB2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (HerceptinTM, Roche), either used alone17 or in combination18 with chemotherapy (e.g. docetaxel), induces a reasonably good response after failing an anthracycline-containing regime. It would appear therefore in patients with tumour overexpressing c-erbB2 the choice of cytotoxic therapy after failing an anthracycline-containing regime is a combination of a taxane and HerceptinTM.

|

|

(b) |

Endocrine therapy

The first line endocrine therapy for premenopausal patients is ovarian ablation which can take the form of oophorectomy, ovarian irradiation or a luteinising hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist (e.g. goserelin). The combined use of ovarian ablation and tamoxifen has been shown to produce both a better endocrine effect and a better efficacy when compared to ovarian ablation alone.19,20 Nevertheless, although the CHAT meta-analysis has shown that the combination of goserelin and tamoxifen is better than one, it remains unclear whether concurrent therapy with both these agents is superior to the use of the two agents sequentially. The standard second line endocrine therapy used to be megestrol acetate (megace), a progestogen, but in the last 3-4 years it has been replaced by non-steroidal selective aromatase inhibitors (e.g. anastrozole, letrozole) due to better efficacy and/or side-effect profile.21-23 The strategies of using endocrine therapy in MBC are summarised in Table 2.

|

| Table 2: Strategies of using endocrine therapy |

|

Past |

Present |

| 1st line |

Ovarian ablation*/ Tamoxifen |

Ovarian ablation*/ Tamoxifen |

|

2nd line

|

Megestrol acetate |

Selective aromatase inhibitor |

| 3rd line |

Aminoglutethimide |

Megestrol acetate |

|

* Oophorectomy/Radiation menopause/LHRH agonist (e.g. goserelin)  tamoxifen tamoxifen

Remarks: See text for details.

|

Recently a new steroidal selective aromatase inhibitor, exemestane, has been shown to have better efficacy and side effect profile compared to megace when used as a second line therapy for MBC.24 Furthermore exemestane appears to be useful even after failing one of the third generation non-steroidal selective aromatase inhibitors.25 It can therefore be considered to be used either as a second line therapy or as a third line therapy after anastrozole or letrozole. Some clinicians would still use megace as third line therapy after anastrozole or letrozole and use exemestane as fourth line therapy in appropriate patients.

Recent results of two prospective, randomised, double-blind trials comparing anastrozole directly with tamoxifen as first line treatment have confirmed therapeutic equivalence of anastrozole versus tamoxifen. In fact the data shows that anastrozole is superior to tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor positive tumours26,27 and in this group of patients anastrozole should be regarded as treatment of choice. A randomised trial comparing letrozole with tamoxifen have shown similar results.28 Further ongoing studies of endocrine therapy include randomised trials comparing the new anti-oestrogen FaslodexTM with tamoxifen and with anastrozole as first and second line therapy. In Nottingham the combination of gamma linoleic acid and tamoxifen has been shown to produce more profound initial anti-tumour effects both clinically (in terms of more rapid responses) and also biologically (e.g. down-regulation of ER).29 Its long term benefits are

Assessment of response

Assessment of response to a systemic therapy is important in several respects. The most effective treatment can be given and a survival benefit as well as an improved quality of life due to better control of the disease can be achieved. An ineffective treatment (and hence its resultant side effects) can be discontinued so that the quality of life can be further improved. Significant cost-savings can be achieved since expensive but ineffective treatments are discontinued and the most effective treatments are targeted. Furthermore evidence of an objective response to one therapy will influence selection of subsequent therapies.

|

The response to systemic therapy for a patient with MBC is generally assessed in the following ways.

|

(i) |

Symptoms

|

|

- |

Improvement (or deterioration) in symptoms is crucially important in the treatment of patients with MBC. However there may be no correlation between symptoms and objective response. The clinician therefore needs to be cautious in interpreting and managing a particular symptom. For instance, a flare reaction with increasing bone pain is fairly common in patients showing an early response to tamoxifen. Symptomatic improvement can be due to effective palliative measures (e.g. pain relief as a result of analgesics) while some symptoms can be due to the side effects of an effective therapy (e.g. nausea and vomiting from cytotoxic therapy).

|

(ii) |

Objective measurements |

|

|

(a) |

International Union Against Cancer (UICC) criteria

|

|

|

|

-

|

Conventional criteria for objective assessment by clinical and/or radiological measurements of tumours are laid down by the UICC (Table 3).30 Objective measurements can complement clinical assessment by symptoms as a measurable increase or shrinkage of the tumour can be seen. However UICC criteria only measure changes in tumour bulk (i.e. dimensions) but lack information on tumour dynamics (e.g. a histologically complete response can be seen at operation for a tumour which has been assessed as 'static' by UICC criteria after neoadjuvant chemotherapy - the measured 'bulk' being composed of fibrous and/or necrotic tissue without viable tumour). Furthermore up to 40% of MBC (e.g. sclerotic bone metastases, pleural effusion, ascites, irradiated lesions) are not measurable and/or assessable by UICC criteria.31 The clinician therefore needs to be aware of their limitations when using UICC criteria. As will be described below biochemical assessment using blood tumour markers may prove to be a better form of assessment of therapeutic response.

|

| Table 3: Assessment of therapeutic responses - International Union Against Cancer (UICC) criteria |

|

Response category

|

Definition

|

|

Complete response (CR)

|

Complete disappearance of lesion

|

|

Partial response (PR)

|

>50% reduction of bi-dimensional product

|

|

Stable disease (SD)

|

25% increase or  50% decrease of bi-dimensional product |

|

Progressive disease (PD)

|

>25% increase of bi-dimensional product or appearance of a new lesion

|

|

|

(b) |

Blood tumour markers

|

|

|

|

-

|

Assessment by blood tumour markers has been shown to be more objective, reproducible and cost-effective.11,32 Carcinoembryonic antigen and a MUC1 mucin (e.g. measured as CA15.3 or CA27.29) are most widely studied. The Nottingham group has devised a biochemical index score comprising CA15.3, CEA and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) for monitoring patients on systemic therapy for MBC (Table 4). The method has been prospectively proven, in monitoring both endocrine therapy and chemotherapy, in our centre and also in a multicentre study.33-37 Biochemical assessment correlates or predates UICC assessment. When a combination of three markers are used as in the score, around 80% of patients are biochemically assessable before therapy and nearly all patients are assessable during therapy.37 It is also the only validated assessment method in patients with disease unassessable by UICC criteria.38-40 Tumour marker measurement has been recommended as a standard tool of assessing response of MBC to systemic therapy in a recently published set of guidelines for management of bony metastases in the United Kingdom.39

|

| Table 4: Scores for changes in marker concentrations |

| |

Upper limit of normal |

Decrease (>10%) |

Stable (±10%) |

Increase (>10%) |

| CA15.3 |

33 U/ml |

-2 |

+1 |

+2 |

| CEA |

6ng/ml |

-2 |

+1 |

+2 |

| ESR |

20mm/hr |

-1 |

+1 |

+2 |

| Biochemical index score (BIS) |

=

|

Summation of scores for all three markers |

| Biochemical response |

:

|

BIS  0 0 |

| Biochemical progression |

:

|

BIS > 0 |

|

|

Direction of therapy

|

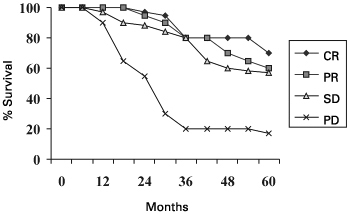

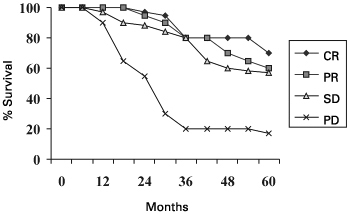

Figure 1: Survival according to response at 6 months on first line endocrine therapy

|

|

| CR versus PR versus SD |

|

ns |

| CR/PR/SD versus PD |

|

P < 0.05 |

|

Conventionally chemotherapy is administered in a fixed number of cycles according to different regimes though it may be discontinued earlier if obvious disease progression is seen. Endocrine therapy, on the other hand, is continued till disease progression occurs. It has been demonstrated that patients with stable disease achieved at 6 months have the same survival as those achieving either a complete response or partial response at 6 months, for first, second, and possibly third line endocrine therapy,41-45 (Figure 1) and possibly also for cytotoxic therapy.41 Patients and clinicians can both be reassured that patients with stable disease are benefiting to a similar extent in terms of survival as patients who achieve a complete or partial response. These findings (classifying patients into 'progressors' and 'non-progressors') therefore emphasise that significantly more patients than previously acknowledged (classifying patients into 'responders' and 'non-responders') appear to benefit from systemic therapies especially endocrine therapy.

Taking the advantages of using blood tumour markers for monitoring response to a systemic therapy, one can extrapolate the potential of therapy directed by marker measurements. Effective therapy can be continued. Ineffective therapy can be discontinued early thus saving the patients from unnecessary side effect and the health care providers from unnecessary expense. Potential cost savings have been estimated.32 A small, randomised study showed that patients receiving continuous chemotherapy as directed by markers had longer survival and better quality of life.36 Larger scale randomised trials are warranted.

|

2. |

Palliative care

All patients with MBC will eventually die from the disease. Although systemic therapies can prolong survival in patients in whom a response is achieved, at some stage of the disease it will often be inappropriate to pursue further systemic therapy. This may be for a variety of reasons such as resistance to a previously effective therapy, intolerance to an ongoing therapy, deterioration in a patient's condition where further therapy is thought inappropriate or the patient chooses to discontinue active anti-cancer treatments.

Palliative care can be instituted and maintained throughout all stages of MBC, aiming at reducing symptoms as a result of the metastatic disease itself, and sometimes, of the treatment given. Owing to the complexity of symptoms due to a variety of presentations of MBC, a multidisciplinary approach using multimodality treatments is mandatory. Both physical and non-physical needs have to be addressed.

|

|

(a)

(i)

|

Physical needs

Pain

|

|

|

- |

Pain is the commonest symptom experienced by patients with cancer. A stepwise approach starting from simple analgesics (e.g. paracetamol), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, to mild to potent opioids is adopted to ensure that the patient is pain-free so that she can enjoy a reasonable quality of life. Drugs can be given in oral form, dermal patches or subcutaneously using syringe drivers. Other useful drugs include tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline) which have adjunctive action to potentiate the analgesic effect of opioids and neuroleptic agents (e.g. carbamazepine) which have distinctive benefits for nerve-related pain (e.g. extensive regional lymph node recurrence associated with brachial plexus compression).

While patients in the late stage of MBC are often given cocktails of analgesics, the side effects (e.g. sickness and constipation as a result of opioids) should be borne in mind. Additional measures and medications to minimise the side effects may be necessary if increasing the dose of opioids is unavoidable. Alternative therapies to control pain include physiotherapy, acupuncture, biofeedback etc.

Occasionally anxiety and other psychological problems can lead to or exacerbate physical pain; the underlying psychological cause has to be treated accordingly (e.g. by counselling).

|

|

(ii) |

Effusions and ascites

|

|

|

- |

Drainage of symptomatic pleural effusion, pericardial effusion and ascites is an effective form of palliative treatment. Treatment of pleural effusion due to MBC is different from benign causes in that the effusion tends to re-accumulate in patients with MBC. Repeated needle aspirations are therefore not advisable since they would lead to loculations further increasing the difficulty of subsequent aspirations. Insertion of a chest drain followed by pleurodesis is preferred. Owing to the danger of pneumothorax and difficulty of subsequent effective aspirations after initial pleurodesis, ultrasound-guided aspiration/drainage is recommended if the effusion re-accumulates and becomes symptomatic.

|

|

(iii) |

Skeletal problems

|

|

|

- |

The bone is the commonest site of metastases from breast cancer. Often the tumour is ER positive and bone metastases respond reasonably well to endocrine therapy and hence quite a large proportion of patients survive for years. Patients who respond to systemic therapy have a good chance of being alive at 3 years and 20% will be alive at 5 years.39 Adequate palliative care is therefore essential to ensure a maximal quality of life.

Bisphosphonates (e.g. pamidronate) have been shown to reduce bone pain, incidence of hypercalcaemia, need for radiotherapy and skeletal complications (e.g. fractures) for patients with lytic bone metastases. They can also be used prophylactically alongside a systemic therapy (e.g. endocrine therapy) prior to the development of skeletal symptoms and complications.46-48

Bone pain can be effectively controlled by radiotherapy and/or bisphosphonates in addition to analgesics.

Up to 40% of patients with bone metastases may develop hypercalcaemia. Hyper-calcaemia results in thirst, drowsiness, nausea, vague abdominal pain, constipation, confusion, coma and death if untreated. Treatment should be vigorous since the condition is often reversible. Acute management includes adequate hydration with normal saline (3-4L per day) and intravenous infusion of bisphosphonates (e.g. pamidronate). Loop diuretics should be avoided unless fluid overload occurs.39

The role of orthopaedic surgical intervention should not be underestimated and identification of an orthopaedic surgeon with a special interest in MBC within the cancer centre is helpful in the delivery of a better service.39 Pain due to nerve entrapment may be relieved by surgical decompression or a nerve block (with local anaesthesia and/or opioids).

Prophylactic fixation prior to radiotherapy is indicated in patients with lytic metastases causing significant cortical destruction in weight-bearing bone (e.g. peritrochanteric region of the femur).49 Management of pathological fractures due to bone metastases differs from that of traumatic fractures since it should be assumed that the former would not heal and the patient has to be mobilised early to achieve a better quality of life owing to the shortened life expectancy. The fractures therefore often need aggressive surgical intervention (with different operative techniques) rather than a conservative approach and radiotherapy generally forms an integral part of the management and is often given after the patient has been operated on and mobilisation can be started.

Spinal cord compression is another oncological emergency which must be treated promptly to avoid permanent neurological damage. The compression can be either of the spinal cord itself or of the cauda equina. This is caused either by visceral type metastases to the spinal cord or from bone metastases to the spinal column which put pressure on the cord by erosion of the bone or by collapse and angulation of the spinal column. Urgent MRI scan is indicated to establish the diagnosis and to evaluate the situation. High dose steroids (with dexamethasone) should be started as soon as possible. Urgent radiotherapy may suffice but if the patient is fit decompression and/or stabilisation surgery should be considered and the opinion of a spinal surgeon should be sought.

|

|

(iv) |

Brain metastases

|

|

|

- |

Most systemic therapies do not cross the blood brain barrier and symptomatic brain metastases are generally treated by whole brain irradiation. Steroids produce a dramatic improvement in the symptoms and should be started as soon as a diagnosis has been made and while radiotherapy is being organised. Most patients with brain metastases will die within a few months from the time of diagnosis and should be given maximal symptomatic care. The role of surgery for solitary brain metastasis is rare but may sometimes be oncologically worthwhile.

|

|

(v) |

Miscellaneous symptoms

|

|

|

- |

It is paramount to look out for and treat an underlying cause of a symptom. Sometimes symptoms are iatrogenic (e.g. sickness and constipation as a result of analgesics and often a systemic therapy) and could be effectively controlled by adjusting the medications. They could also be due to an easily reversible cause (e.g. constipation due to hypercalcaemia, fatigue due to anaemia). Bronchodilators and various cough mixtures are helpful in intractable cough which is a less common symptom in MBC. A cocktail of bronchodilators, steroids and antibiotics may reduce the breathlessness due to lymphangitis carcinomatosa especially in a patient who is not fit for cytotoxic therapy. Steroids may be helpful in alleviating the distending pain of the liver capsule due to a huge metastasis.

|

|

(b)

(i)

|

Non-physical needs

Psychological

|

|

|

- |

Depression, fear and anger occur in different stages of this incurable disease. They can be treated by drugs (e.g. anti-depressants), counselling, behavioural therapy and psychiatric intervention.

|

|

(ii)

|

Social

|

|

|

- |

The social, domicilliary and financial circumstances can be taken care of through involvement of medical social workers, home helpers and/or community nurses.

|

|

(iii) |

Spiritual

|

|

|

- |

The spiritual need has to be recognised and often the provision of a chaplaincy service is helpful. The involvement of the patient's own church or religious community in giving her support may also be useful.

|

The multi-disciplinary advanced breast cancer team

The surgeon, the clinical/medical oncologist and the breast care nurse generally form the core personnel of the multi-disciplinary advanced breast cancer management team. All should have a special interest and had training in advanced breast cancer management. A training in communication skills is absolutely desirable for clinicians involved in the management of patients with MBC. As will be shortly described other personnel are required under different circumstances to provide a comprehensive service to patients with advanced breast cancer.

The surgeon has a central role in establishing and leading a breast unit in that the patient's first contact islikely to be with the breast surgeon. Also the initial treatment of primary breast cancer is currently surgical and this is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Furthermore the surgeon should be prepared to take a joint role with the oncologists in the breast team when assessing and managing patients with advanced disease.50 The breast surgeon retains his role in the management of advanced breast cancer due to at least two reasons. Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy for a large proportion of patients with LAPC. Although Patey mastectomy is the standard procedure and extensive radical procedures are seldom required with the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or preoperative radiotherapy, additional involvement of the thoracic surgeon and/or plastic surgeon may occasionally be required for chest wall resection and complex reconstructive procedures. The other reason is that historically surgeons have a major role in the delivery of systemic therapies especially endocrine therapy. Since Beatson first reported on the use of oophorectomy to treat a patient with advanced breast cancer51 endocrine therapy used to involve surgical ablative procedures (e.g. adrenalectomy, hypo-physectomy) until in the last one to two decades when they have been gradually replaced by pharmacological manipulation. Many surgeons have maintained their interest in endocrine therapies despite the fact that most endocrine treatments are essentially drug based. With the introduction of minimally invasive surgery, patients can now have a choice of laparoscopic oophorectomy as against the use of reversible blockade using an LHRH agonist. The choice between these options may depend on a combination of patient age, patient preference and cost.

The clinical/medical oncologist plays a pivotal role in the use of cytotoxic therapy and radiotherapy (locoregionally as in LAPC and in treating patients with MBC e.g. metastases in bone and brain). In some centres the clinical/medical oncologist also delivers endocrine therapies. There are some oncological emergencies (e.g. spinal cord compression) which require the prompt attention of an oncologist. Other urgent and potentially life-threatening or debilitating circumstances include superior vena caval obstruction, lymphangitis carcinomatosa, brachial plexus compression and bone marrow suppression.

While specialty nurses to provide information regarding radiotherapy and chemotherapy are often available in most oncology units, the breast care nurse offers through-and-through support and care for patients with advanced breast cancer in a comprehensive fashion. Owing to the heterogeneity of presentation and the complexity of needs in patients with advanced breast cancer, especially those with MBC, a breast care nurse dedicated to advanced disease is preferred. The breast care nurse offers support to the patient (and sometimes to her family) in coming to terms with the diagnosis and treatment. She should co-ordinate with other members of the team and if necessary liaise with other disciplines (e.g. palliative care physicians, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, clinical psychologist, chaplain, medical social worker, community nurse, home helper) in order to ensure that the patient's physical and non-physical needs are being adequately attended to. The service should not be limited to clinic appointments or hospital stays. Home visits also form an important component.

The patient and the family physician should also be provided direct access to the team if the need arises. Effective communication should be maintained between the multidisciplinary team and the family physician. While the patient is being assessed by the multi-disciplinary team who initiate and change therapies as appropriate, the family physician can play an important role in continuing the anti-cancer therapy, adjusting medications (e.g. analgesics) and in providing feedback to specialists in the team so that, for instance, the patient may be brought back for an earlier assessment, or management plan can be discussed and clarified at any point during the course of her disease.

Multidisciplinary meeting

Meetings should be held regularly, preferably just prior to the clinic, to assess response of therapy and to discuss management of patients. This is particularly paramount for MBC since the presentation is so complex and heterogeneous. The breast surgeon and clinical/medical oncologist dedicated to advanced breast cancer, as well as the radiologist with a special interest in MBC should form the core personnel of the meeting. At the meeting the radiologist should be aware of the duration of a systemic therapy and the sites of radiotherapy so that imaging results can be properly reviewed for the assessment of therapeutic response. The input of thebreast care nurse is essential in deciding the optimum treatment for an individual patient. Although the best treatment can be decided from an oncological point of view, the choice of the patient is particularly important in this distinct type of disease.

Multidisciplinary clinic

Role fidelity is an important principle of medical ethics. Patients with MBC would be confused with consequent increased anxiety if different messages are conveyed by different clinicians. Based on the contextual circumstances (e.g. interest and training of available clinicians, availability in manpower in different disciplines), the team should decide on the roles of different disciplines in the clinic. One option is for the surgeon to be responsible for surgical issues and the delivery of endocrine therapy (if he/she has developed an interest in endocrine therapy) and for the clinical/medical oncologist to deliver chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. The breast care nurse should be involved in all circumstances which require the breaking of 'bad' news (e.g. new diagnosis of metastases, progression on an existing therapy) and in cases when additional psychosocial support is expected.

Audit and research

Audit on clinical data and performance is becoming an essential component of virtually all forms of clinical practice. This should be carried out in a computerised fashion by dedicated data personnel who, depending on the need of individual hospitals, might work as part of the audit service for the whole hospital or department. The audit process should aim at improving present clinical practice and its contents may include constructing a database of patients with advanced breast cancer with regular review of data on survival, response to a therapy, for example. It may also involve a particular treatment regime e.g. the use of bisphosphonates in different categories of patients with bone metastases.

With the design of a multidisciplinary approach, various research projects can be streamlined. The surgeon can be the principal investigator of various endocrine therapy trials (e.g. the new pure anti-oestrogen, steroidal selective aromatase inhibitor) while the clinical/medical oncologist can direct chemotherapy studies (e.g. taxanes, HerceptinTM). The radiologist can pursue on the radiological presentations, changes and assessment for patients with MBC (e.g. the use of MRI scan for assessing therapeutic response). Psychosocial assessments and quality of life studies can be co-ordinated by the breast care nurse. There is evidence to suggest that patients treated in centres actively involved in research have improved outcomes.52

|

Key messages

|

|

1.

|

Locally advanced primary breast cancer:

|

|

a) |

It is a heterogeneous disease.

|

|

b) |

Metastatic work-up is required at diagnosis.

|

|

c) |

Treatment generally includes the use of systemic therapy in the form of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and radiotherapy. Initial endocrine therapy is an alternative especially for oestrogen receptor positive tumours.

|

|

| 2. |

Metastastic breast cancer:

|

|

a) |

It is not curable but treatable.

|

|

b) |

Treatment aims at improving quality of life. It consists of (i) systemic therapy in the form of cytotoxic or endocrine therapy; (ii) palliative care for control of symptoms with attention to both physical and non-physical needs. Survival may be improved in patients who respond to systemic therapy.

|

|

c) |

Therapeutic response is assessed by (i) symptoms; and (ii) objective measurements (including both clinical/radiological and biochemical assessments).

|

|

| 3. |

Advanced breast cancer is best managed by a multidisciplinary team comprising the surgeon, clinical/medical oncologist, radiologist and breast care nurse as core personnel.

|

K L Cheung, DM, FRCSEd, FHKAM(Surgery), FACS

Consultant Breast Surgeon,

S Y Chan, DM, MRCP, FRCR

Consultant Clinical Oncologist,

A J Evans, MBChB, MRCP, FRCR

Consultant Radiologist,

L Winterbottom, SRN, NDNCert

Macmillan Breast Care Nurse,

J F R Robertson, BSc, MD, FRCS (Glasg)

Professor of Surgery,

City Hospital, Nottingham, U.K.

Correspondence to :

Mr K L Cheung, Professorial Unit of Surgery, City Hospital, Hucknall Road, Nottingham NG5 1PB United Kingdom.

References

- Cheung KL. Management of primary breast cancer. HK Pract 1997;19:256-263.

- Cheung KL. Management of primary breast cancer in Hong Kong - Can the guidelines be met? Eur J Surg Oncol 1999;25:255-260.

- Haagensen CD, Stout AP. Carcinoma of the breast 2: criteria for operability. Ann Surg 1943;118:859-870.

- Willsher PC, Robertson JFR, Armitage N et al. Locally advanced breast cancer: Long term results of a randomised trial comparing primary treatment with tamoxifen or radiotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol 1996;22:43-47.

- Rubens RD, Bartelink H, Englesman E et al. Locally advanced breast cancer: the contribution of cytotoxic and endocrine treatment to radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1989;25:667-678.

- Willsher PC, Robertson JFR, Chan SY et al. Locally advanced breast cancer: early results of a randomised trial of multimodal therapy versus initial hormone therapy. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:45-49.

- Tan SM, Cheung KL, Willsher PC et al. Locally advanced primary breast cancer - Medium term results of a randomised trial of multimodal therapy versus initial hormone therapy. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:2331-2338.

- Fisher ER, Wickerham DL, Wolmark N et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2483-2493.

- Fisher B, Bryant J, Wolmark N et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on the outcome of women with operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2672-2685.

- Cheung KL, Howell A, Robertson JFR. Preoperative endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2000;7:131-141.

- Cheung KL, Graves CRL, Robertson JFR. Tumour marker measurements in the diagnosis and monitoring of breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2000;26:91-102.

- Hayes DF, Henderson IC, Shapiro CL. Treatment of metastatic breast cancer: present and future prospects. Semin Oncol 1995;22:5-19.

- Gianni L, Capri G. Experience at the Instituto Nazionale Tumori with paclitaxel in combination with doxorubicin in women with untreated breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S3-S1-S3-S3.

- Gianni L, Dombernowsky P, Sledge G et al. Cardiac function following combination therapy with Taxol and doxorubicin for advanced breast cancer. Program and Proceedings of ASCO Annual Meeting 1998; Abstract 444.

- Paridaens R, Biganzoli L, Bruning P et al. Paclitaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line single-agent chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomised study with crossover. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:724-733.

- Blum JL, Buzdar AU, LoRusso PM et al. A multicenter phase II trial of xelodatm (capecitabine) in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. Program and Proceedings of ASCO Annual Meeting 1998; Abstract 476.

- Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D et al. Efficacy and safety of HerceptinTM (humanised anti-her2 antibody) as a single agent in 222 women with her2 overexpression who relapsed following chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Program and Proceedings of ASCO Annual Meeting 1998; Abstract 376.

- Slamon D, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S et al. Addition of HerceptinTM (humanised anti-HER2 antibody) to first line chemotherapy for her2 overexpressing metastatic breast cancer markedly increases anti-cancer activity: a randomised, multinational controlled phase III trial. Program and Proceedings of ASCO Annual Meeting 1998; Abstract 377.

- Robertson JFR, Walker KJ, Nicholson RI et al. Combined endocrine effects of LHRH agonist (Zoladex and tamoxifen (Nolavdex therapy in premenopausal women with breast cancer. Br J Surg 1989;76:1262-1265.

- Klijn JGM, Blamey RW, Boccardo F et al. Combined tamoxifen and luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist versus LHRH agonist alone in premenopausal advanced breast cancer: a meta-analysis of four randomised trials. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:343-353.

- Buzdar AU, Jones SE, Vogel CL et al Arimidex Study Group. A phase III trial comparing anastrozole (1 and 10 milligrams), a potent and selective aromatase inhibitor, with megestrol acetate in postmenopausal women with advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer 1997;79:730-739.

- Buzdar AU, Jonat W, Howell A et al. Arimidex Study Group. Anastrozole versus megestrol acetate in the treatment of postmenopausal women with advanced breast carcinoma: results of a survival update based on a combined analysis of data from two mature phase III trials. Cancer 1998;83:1142-1152.

- Dombernowsky P, Smith G, Falkson G et al. Letrozole, a new oral aromatase inhibitor for advanced breast cancer: double-blind randomised trial showing a dose effect and improved efficacy and tolerability compared with megestrol acetate. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:453-461.

- Kaufmann M, Bajetta E, Dirix LY et al. Survival advantage of exemestane (EXE, Aromasin over megestrol acetate in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer refractory to tamoxifen: results of a phase III randomised double-blind study. Program and Proceedings of ASCO Annual Meeting 1999; Abstract 412.

- L

nning P, Bajetta E, Murray R et al. A phase II study of exemestane in metastatic breast cancer patients failing non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1998;50:3043. nning P, Bajetta E, Murray R et al. A phase II study of exemestane in metastatic breast cancer patients failing non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1998;50:3043.

- Bonneterre J, Thlimann D, Robertson JFR et al for the Arimidex Study Group. Anastrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer in 668 postmenopausal women: results of the Tamoxifen or Arimidex Randomised Group Efficacy and Tolerability Study. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3748-3757.

- Nabholtz JM, Buzdar A, Pollak M et al for the Arimidex Study Group. Anastrozole is superior to tamoxifen as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: Results of a North American multicenter randomised trial. J Clin Oncol 18:3758-3767.

- Mouridsen H, P

rez-Carri rez-Carri n R, Becquart D et al. Letrozole International Breast Cancer Study Group. Letrozole (Femara n R, Becquart D et al. Letrozole International Breast Cancer Study Group. Letrozole (Femara ) versus tamoxifen: preliminary data of a first-line clinical trial in postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2000;36(Suppl 5):S88, Abstract 220. ) versus tamoxifen: preliminary data of a first-line clinical trial in postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2000;36(Suppl 5):S88, Abstract 220.

- Kenny FS, Pinder SE, Ellis IO et al. Gamma linolenic acid with tamoxifen as primary therapy in breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2000;85:643-648.

- Hayward JL, Carbone PP, Heuson JC et al. Assessment of response to therapy in advanced breast cancer. Cancer 1997;39:1289-1293.

- Whitlock JPL, Evans AJ, Jackson L et al. Imaging of metastatic breast cancer: distribution and radiological assessment of involved sites at presentation. Clin Oncol 2001;13:181-186.

- Robertson JFR, Whynes DK, Dixon A et al. Potential for cost economics in guiding therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1995;72:174-177.

- Williams MR, Turkes A, Pearson D et al. An objective biochemical assessment of therapeutic response in metastatic breast cancer: a study with external review of clinical data. Br J Cancer 1990;61:126-132.

- Robertson JFR, Pearson D, Price MR et al. Objective measurement of therapeutic response in breast cancer using tumour markers. Br J Cancer 1991;64:757-761.

- Dixon AR, J

nrup I, Jackson L et al. Serologic monitoring of advanced breast cancer treated by systemic cytotoxic using a combination of ESR, CEA and CA 15.3: fact or fiction? Disease Markers 1991;9:167-174. nrup I, Jackson L et al. Serologic monitoring of advanced breast cancer treated by systemic cytotoxic using a combination of ESR, CEA and CA 15.3: fact or fiction? Disease Markers 1991;9:167-174.

- Dixon AR, Jackson L, Chan SY et al. Continuous chemotherapy in responsive metastatic breast cancer: a role for tumour markers? Br J Cancer 1993;68:181-185.

- Robertson JFR, Jaeger W, Syzmendera JJ et al. The objective measurement of remission and progression in metastatic breast cancer by use of serum tumour markers. Eur J Cancer 1999;35:47-53.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumour markers in breast and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:2843-1877.

- Breast Specialty Group of the British Association of Surgical Oncology. The guidelines for the management of metastatic bone disease in breast cancer in the United Kingdom. Eur J Surg Oncol 1999;25:3-23.

- Cheung KL, Evans AJ, Robertson JFR. The use of blood tumour markers in the monitoring of metastatic breast cancer unassessable for response to systemic therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;67:273-278.

- Howell A, Mackintosh J, Jones M et al. The definition of the 'no change' category in patients treated with endocrine therapy and chemotherapy for advanced carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1988;24:1267-1272.

- Robertson JFR, Williams MR, Todd J et al. Factors predicting the response of patients with advanced breast cancer to endocrine (Megace) therapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1989;25:469-475.

- Robertson JFR, Willsher PC, Cheung KL et al. The clinical relevance of static disease (no change) category for 6 months on endocrine therapy in patients with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:1774-1779.

- Robertson JFR, Howell A, Buzdar A et al. Static disease on anastrozole provides similar benefit as objective response in patients with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999;58:157-162.

- Cheung KL, Robertson JFR. The importance of stable disease in breast cancer patients treated with endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Abstracts 1999;1:2-4.

- Paterson AH, Powles TJ, Kanis JA et al. Double-blind controlled trial of clodronate in patients with bone metastases from breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:59-65.

- Conte PF, Giannessi PG, Latreille J et al. Delayed progression of bone metastases with pamidronate in breast cancer patients: a randomised, multicenter phase III trial. Ann Oncol 1994;5(Suppl 7):S41-S44.

- Hortobagyi GN, Theriault RL, Porter L et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal complications in patients with breast cancer and lytic bone metastases. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1785-1789.

- Mirels H. Metastatic disease in long bones. A proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fracture. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1989;249:256.

- Breast Specialty Group of the British Association of Surgical Oncology. The British Association of Surgical Oncology guidelines for surgeons in the management of symptomatic breast disease in the UK (1998 revision). Eur J Surg Oncol 1998;24:464-476.

- Beatson GT. On the treatment of inoperable cases of carcinoma of the mamma: suggestions for a new method of treatment with illustrative cases. Lancet 1896;2:104-107.

- Stiller CA. Survival in patients with breast cancer: those in clinical trials do better. Br Med J 1989;299:1056-1059.

|