|

October 2002, Volume 24, No. 10

|

Update Article

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

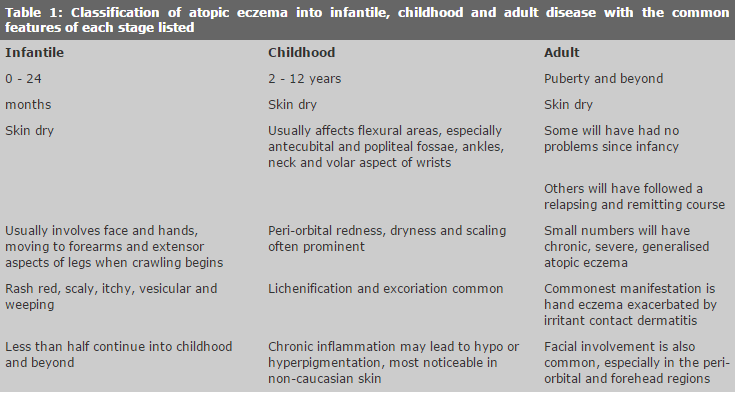

Treatment of atopic eczema in adults and childrenA Drummond, F A Campbell, D T Roberts HK Pract 2002;24:480-489 Summary Atopic eczema is an increasingly prevalent condition that follows a relapsing and remitting course. It predominates in infancy and childhood but may persist or recur in adults. Management is aimed at preventing dryness, itch and inflammation whereas treatment is directed at disease activity and its suppression. Both should address the emotional and physical symptoms and be tailored to the individual patient. Primary care physicians will frequently be involved in the diagnosis and management of patients with eczema. Many will respond to the regular application of emollients and the intermittent use of topical steroids while others will follow a more chronic course necessitating second or third line therapy. 摘要 特異性濕疹發病率逐漸增加。病情反覆,時而緩 解,時而復發。最常見於嬰兒和兒童期,但可以遷延不愈,或成年時再發作。治療的目的是預防乾燥,痕 癢和發炎,針對患處活動性和抑制病情,要留意病人心理、生理兩方面的症狀,治療要因人而異。家庭醫 生常見到濕疹病人,給予潤滑藥和間歇使用類固醇後大部份患者會好轉。但有些轉為慢性,需要採用第二 或第三線的藥物。 Introduction Atopic eczema is a chronic, pruritic, relapsing and remitting skin condition affecting 10 - 15% of the population1 and usually presenting within the first 12 months of life. Although a large proportion remit by their mid-teens, 60% of patients go on to develop problems with dry, "sensitive" skin which predisposes them to eczematoid eruptions in later life.2 There is often a family history of atopy in the form of asthma, eczema or allergic rhinitis and although the predisposition to eczema may be inherited, environmental factors play a role in both the aetiology and the management of the disease. These environmental factors may contribute to the observed increase in the disease over the last 30 - 40 years3 during which people have become accustomed to living in warm, centrally-heated environments, having numerous irritant cosmetics and cleaning agents at their disposal and generally leading more stressful lives. The presentation of atopic eczema (Figures 1-3) is dependent on the age of the patient and falls into three broad categories which may be separated by periods of remission or which may blend into one another - Table 1.

Explanation and education Patients and carers should be made aware of the nature of their disease and its normally good prognosis. They should be advised that the condition is "controllable" rather than "curable" and that there is often no explanation for their flare-ups. In children there may be psychological upset arising from the constant necessity to apply treatment and from the inability to participate in activities that can exacerbate their eczema such as swimming. Adolescents often have problems with confidence, self-esteem and body image, perceiving themselves as unattractive, thereby withdrawing from their social group. Teenagers and adults will benefit from careers advice and should avoid certain occupations such as nursing or hairdressing where there is much "wet work" and exposure to irritants. Employment in industry where there is contact with irritant oils and chemicals should also be avoided. Avoidance of precipitating factors and irritant Central heating, double-glazing and draught-proofing all contribute to an increase in the ambient temperature within the home and this in turn creates a warm, dry environment that is hostile to eczematous skin. Increased frequency of personal washing coupled with the more liberal use of soaps, shower gels and bubble baths leads to a marked rise in the exposure of skin to agents which tend to aggravate eczema. The use of convenience-products such as surfactant and perfume-impregnated hygienic wipes that decrease the integrity of the epidermal barrier can exacerbate the problem. These should be avoided where possible. Fabrics such as wool, synthetics (like nylon) or dyed fabrics can irritate eczema sufferers and should also be avoided if possible. Treatment of itch Scratching can be minimised by keeping fingernails short and if necessary, applying occlusive dressings to affected areas of skin. Tar or ichthammol bandages may be beneficial for overnight use. For severe involvement, sedating oral antihistamines are helpful for relief of itch but patients should be warned of their side effects. Behaviour therapy techniques can help to treat the compulsive scratching observed in many atopics.4 Emollients While excessive washing and the use of soaps can exacerbate skin dryness, bathing can also be beneficial when emollient bath oils are used and moisturisers applied immediately thereafter. This apparent conflict should be explained to the patient or carer so that they are more likely to comply with a 15-minute soak in an emollient-containing bath followed by the liberal application of moisturising cream or ointment to damp skin. Emollient bath products may contain antiseptic or antipruritic agents but occasionally these may cause discomfort and compound the symptoms. Many moisturising creams can also be used as soap substitutes but some patients dislike their lack of lather. Topical steroids

If emollients and good skin care fail to control activity then the mainstay of therapy are topical steroids. It is vital for the practitioner to promote the benefits of such agents rather than enhance the patient's fear of using them. In general, 1% hydrocortisone is rarely an effective treatment but is often viewed as a strong steroid by patients and parents. As a general rule mild to moderately potent steroids are used in infants and children whereas stronger preparations can be used in adults. On certain sites, such as the face and flexures, weak to moderately potent steroids are advised. Adequate supervision and avoidance of prolonged use will minimise side effects such as skin atrophy and striae (Figure 4). Children, especially infants, should be closely monitored in case systemic absorption results in growth retardation or adrenal suppression. This, however, is a rare complication when topical steroids are used properly. Table 2 lists the therapeutic potencies of topical steroids into mild, moderate, potent and very potent.

Treatment of infection Bacterial

Staphylococcus aureus is commonly cultured from eczematous skin and is frequently implicated in secondary infection. Active eczema which is secondarily infected can be identified clinically by the presence of yellow crusting on the skin. If such infection is widespread a systemic antibiotic should be prescribed which can be used in conjunction with a topical steroid. More localised infection can be treated with a combination preparation containing a topical steroid plus an antiseptic or an antibiotic. There are many such combinations on the market. When the infection has cleared topical antibiotics should be replaced with a pure steroid preparation to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance developing. Prolonged courses of oral antibiotics are required in those patients where recurrent episodes of infected eczema are frequent and remissions short lived. Viral Herpes simplex infection may be severe and generalised in atopics (Figure 5) and such patients will usually require hospital admission for isolation, nursing care and intravenous antiviral agents. Steroids should not be applied to affected areas. Atopics are also more prone to infection with viral warts and molluscum contagiosum. Mollusca should be covered where possible and steroid use near the lesions discontinued.

These drugs are topical immunomodutators and as such should be capable of selectively modifying the immune system within the skin without a systemic effect. Both drugs are macrolide molecules that inhibit T-cell activation in a similar fashion to cyclosporin. The two drugs are currently approved for use in atopic dermatitis in many countries. Both are licensed for use in adults and children and clinical trials show them to be effective. The major side effects are local irritation with burning, pruritus and erythema but these tend to diminish as treatment progresses. The long-term toxicity of these topical immunomodulators remains unclear and will become apparent with time.

Bandaging techniques Wet wrap dressings, with or without mild topical corticosteroids, can be effective if the child is co-operative.5 This technique aims to 'overdose' the skin with moisturisers to prevent it drying too fast and to control inflammation with a mild topical steroid under occlusion. It can be useful in treating poorly controlled eczema and can reduce itch. It promotes skin healing as the bandages provide a physical barrier against scratching. Initially the dressings are applied daily after bathing and the treatment continued for a variable length of time until the skin is clear. The wet wraps can be applied over-night in school-aged children but this may not be as effective as continuous wrapping. The first layer of tubular bandages is cut and soaked in warm water while the emollient and topical steroid is applied to the child. The excess water is squeezed out of the wet bandages and these are applied when warm to the body. A second dry layer is then placed over the wet layer (Figure 6a-e). Zinc paste and Ichthammol bandages can be useful in poorly controlled eczema in both adults and children. They are messy to apply and are often used when the patient is attending a dermatology day treatment unit or admitted to an in-patient bed for treatment.

The role of allergy in atopic dermatitis is controversial and often over emphasised in the lay press. It is not a primary aetiology in this disease but rather a secondary phenomenon. Allergen avoidance is therefore a second line treatment rather than a first. Food Allergens Food allergy is thought to play a role in a small subset of patients, particularly infants and young children.6 The gold standard test for food allergy is a double blind oral food challenge in a hospital setting. Most children will outgrow their food allergies and so the problem is rarely of importance in older children and adults. It is important not to suggest food exclusion diets to parents of atopic children without assessment by a dermatologist and a paediatric dietician. House Dust Mite (HDMs) Environmental allergens, most importantly HDM, seem to play a variable role in the maintenance of atopic dermatitis in some patients. The HDM is a major indoor allergen and several studies have evaluated the effect on disease activity with HDM eradication programmes.7,8 These programmes tend to involve encasing mattresses and pillows, a weekly hot wash of bedding, frequent vacuum cleaning of living and bedrooms, soft toys and carpets are regularly cleaned or removed and pets excluded. These procedures are time consuming and can be expensive. The studies have shown some benefit with these measures,7 mainly in the children. HDM avoidance is usually suggested to those children and adults whose dermatitis is not controlled with first line and other second line treatments. Psychological support The majority of patients with atopic dermatitis will be diagnosed and managed by their primary care physician. Chronic disease is notably disruptive to family life. The negative impact of a scratching and fractious child and associated sleep deprivation cannot be over emphasised. Such children and their families require psychological support the mainstay of which is constant reassurance that the disease is controllable if not curable. The primary care physician is in an excellent position to provide this reassurance to the majority of patients. However, a small subgroup that does not respond to conventional therapy will require formal psychological support with clinical psychoanalysis and input from a psychologist. Oral gamolenic acid The evidence for this therapy in atopic eczema is inconclusive.9 It appears to be more helpful in children compared to adults. It should be given for a trial period of 3 months and only continued beyond this period if there is obvious clinical benefit. Out-patient treatment unit The out patient treatment unit is an ideal place to educate patients and parents on atopic eczema. A dermatology-trained nurse can demonstrate the application of their treatment and bandages. Patients can also attend to have their treatments applied by the nurse and this often results in more rapid remission of their dermatitis. In-patient treatment Patients are generally admitted if their disease has failed to respond to all other first and second line treatments and when they are unwell, often secondary to infection. It is not uncommon for patients to improve in hospital with the treatment that has allegedly been used in the home environment. Bandages are more easily applied in a hospital setting and appropriate treatment for infection can be administered. It is important for ongoing eczema education to be given during an in-patient stay.

These treatments are reserved for the patients with severe disease that has failed to respond to first and second line therapies and should only be prescribed and supervised by a dermatologist. They are used more frequently in adult patients but may be required in children with recalcitrant disease. The choice of treatment is based on an evaluation of the patient, their ability to use the treatment and the ratio of risk and benefit to the individual. Each treatment has potential side effects that must be considered before starting any of these therapies.

PUVA This treatment combines an oral or topical photosensitising agent, psoralen, with UVA phototherapy. It can be used for older children and adults but requires regular attendance at a hospital-based dermatology unit. Studies have shown that prolonged treatment courses are usually required to induce clearance but long-term remissions have been documented.10The risk of photocarcinogenesis is the major problem with PUVA and therefore treatment should be reserved for the most severe and recalcitrant patients. UVB Narrow band (TL-01) UVB phototherapy is generally given more frequently but does not require the patient to take any oral photosensitising medication. Long treatment courses are often required to induce remission but long-term benefits have been reported.11 The potential risk of photocarcinogenesis is again a limiting factor with this treatment. UVA1 UVA1 therapy appears promising in the treatment of atopic eczema12 but this type of phototherapy is not yet widely available and clinical experience is limited.

Oral steroids Systemic corticosteroid therapy is effective for most patients. However, rapid recurrence after discontinuation of treatment and high risk of potential side effects precludes their use. Atopics are often prescribed oral steroids for asthma, which can complicate the management of the co-existing eczema. Cyclosporin Cyclosporin, a T-cell modulator, is extremely effective in the treatment of atopic dermatitis and has been used in both adults and children.13 It induces rapid remission but relapse rates are high after discontinuation of treatment. Intermittent use has been shown to be as effective as continuous reducing dosage and so there is a tendency to prescribe it for short periods of 8-16 weeks, as required. It has several potentially serious side effects that require the patient to be closely supervised. Symptomatic side effects such as tremor, paraesthesia, gastrointestinal disturbance, hypertrichosis and gingival hypertrophy are totally reversible on withdrawal of the drug. However, nephrotoxicity and hypertension may be severe and occasionally permanent. There is also a risk of future development of malignancies that requires to be discussed with patients prior to instituting this treatment. Azathioprine This drug has long been used as a steroid sparing agent but has been shown to be effective in the treatment of atopic dermatitis as a single agent in both adults and children.14 It is generally well tolerated and now with the ability to test for thiopurine methyltransferase, a predictor of severe myelosupression, side effects can be minimised by reserving its use for those with adequate enzyme levels. It can be used for lengthy periods although long-term toxicity of this drug remains unclear. As with all the systemic treatments regular monitoring of the patient is required. Others Many other therapies have been reported as treatment for atopic dermatitis but are not routinely or regularly used. All are prescribed by an experienced dermatologist to individual cases if all other treatment had failed. Conclusion General practitioners will be involved in the management of many patients with atopic eczema. Most will have mild disease that is adequately controlled with first line treatments. A small proportion will require more aggressive therapy that may necessitate referral to a dermatologist for consideration of second or third line treatments. The primary care physician is in an excellent position to provide psychological support to the patient and family. This approach, in conjunction with secondary care intervention where appropriate, promotes emotional and physical well being thereby minimising the impact of the disease on the patient's life.

A Drummond, BSc, MBChB, MRCP(UK)

D T Roberts, MBChB, FRCP(Glasg) Specialist Registrar in Dermatology, North Glasgow University Hospitals Trust, Royal Infirmary. Correspondence to: Dr D T Roberts, South Glasgow University Hospitals Trust, Southern General Hospital, Glasgow G51 4TF, U.K. References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||