|

April 2003, Volume 25, No. 4

|

Original Article

|

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in a regional geriatric day hospitalK W Wong 黃桂榮, R Fung 馮子恩, P T Lam 林寶鈿, D V K Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2004;26:172-179 Summary

Objective: To study the prevalence of depressive symptoms in a regional

geriatric day hospital

Keywords: Prevalence; geriatric day hospital; depressive symptoms; 15-item Chinese version Geriatric Depression Scale 摘要

目的: 在一個地區性的老人日間醫院內,研究病人抑 鬱病徵的普及性。

Introduction In Hong Kong, as in Western countries, the number of elders is increasing. The percentage of the elderly population has risen from 10.2% of the population aged 65 and over in 1996 to 11.2% in 2001.1 It has been projected that by 2031, 24% of our total population will be over 65.2 Depression is a common problem in the geriatric population. A previous local study revealed that the prevalence of depression in a community elderly Chinese population was as high as 35%.3 However, there is ample evidence that depression is under-recognised in the primary and secondary care, and it is under-treated when recognised.4-6 Geriatric patients, after prolonged hospitalisation for their acute medical problems, may become de-conditioned from their premorbid state. Some of these patients probably need re-conditioning exercises or physical rehabilitation before they can restore their maximum functional capacity. The risk of depression has been estimated to be threefold greater for elders with disability as compared with those without. Therefore, depression is commonly found in elderly patients commencing rehabilitation.7 Depression at the start of rehabilitation is also found to be associated with failure to restoration to their premorbid function capacity.8 For example, the rehabilitation of depressed stroke patients is more difficult than the rehabilitation of patients who are not depressed: their recovery in hospital is slower and less successful, they are less likely to regain normal lifestyles after discharge, and they have poorer long term survival rates.9 Geriatric day hospitals have been playing a major role in the rehabilitation of older people.10 A significant proportion of patients referred to geriatric day hospitals suffer from cerebrovascular accidents, recent hip fractures and Parkinsonism. With these co-morbidities, the prevalence of depression would be expected to be higher in this group of patients when compared with healthy community elders.11 However, little data is available for the prevalence of depression in local geriatric day hospitals. It is important to recognise and treat depression in this group of patients as it may result in delayed recovery of illness or even failure of physical rehabilitation. In order to increase the detection rate of possible depressive illness, routine use of assessment tools has been suggested.12 We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in a local regional geriatric day hospital by using the 15-item Chinese version Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) as a screening tool. We also attempted to identify possible risk factors for depressive symptoms in a geriatric day hospital setting. Method Study design A cross-sectional survey was conducted to determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Yung Fung Shee Geriatric Day Hospital (YFSGDH). Subjects The study was conducted in YFSGDH, a regional geriatric day hospital under the Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital in Kowloon East area. It has a daily maximum capacity of 80 patients. It receives referrals from physicians in the public sector and through the Community Geriatric Assessment Teams. The YFSGDH receives a wide spectrum of cases for outpatient rehabilitation including stroke, Parkinsonism, hip fracture, and physical de-conditioning after an acute illness episode. All new patients referred to YFSGDH from 1st January to 31st March 2002 were potential participants. Each new patient was assessed within one week of admission for the presence of depressive symptoms. The GDS was used as a screening instrument. Patients were excluded from the study if they were less than 65 years old, or had a past history of psychiatric illness or of cognitive impairment with mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score of less than 15,13 or they were unable to communicate, for example, having severe hearing impairment or dysphasia. Outcome measures The GDS has a high sensitivity and specificity and has been validated against psychiatric criteria.14,15 The sensitivity and specificity are 96.3% and 87.5% respectively for detection of depression using a cut-off point of 8.3 Hence, the depressive symptoms are thought to be significant when GDS score 8. It is recommended as a useful screening instrument for detection of depression in elderly patients both in the hospital and general practice.12 Two trained medical staff administered the GDS with the subjects in YFSGDH during their visits. All questions were standardised and asked in exactly the same phrases in Cantonese. Demographic variables including age, gender, financial conditions, marital status, housing and reason of referral were collected. The MMSE score, Bathel Index (BI) and Elderly Mobility score (EMS) were also collected for analysis. For the measurement of severity of disability, BI and EMS were used. BI consists of 10 items of basic activity of daily living (ADL), with a total score of 100 (bowel control 10; bladder control 10; grooming 5; toilet use 10; feeding 10; transfer 15; mobility 15; dressing 10; stairs 10; and bathing 5). The severity of disability in ADL was categorised into three groups: (1) Severe, with BI<50; (2) Moderate, with BI=50-75; and (3) Mild, with BI>75.16 EMS consists of 7 items with a maximum score of 20 (lying to sitting 2; sitting to lying 2; sit to stand 3; stand 3; gait 3; timed walk 3; functional reach 4). Statistical analysis SPSS 10.0 for Windows statistical software was used in the analyses. Comparisons between groups were made by Chi-square test. The level of significance was set at 5% in all the comparisons, and all statistical testing was two sided. Result There were a total of 255 new referrals to YFSGDH during the study period. One hundred and seven cases were excluded from the study (less than 65 years old, n=25 (23.4%); history of psychiatric illness or cognitive impairment, n=11 (10.3%); MMSE score less than 15, n=33 (30.8%); unable to communicate, n=32 (29.9%); and others, n=6 (5.6%)). One hundred and forty-eight new referrals were analysed. Their demography is shown in Table 1. Eighty-nine (56.4%) patients were more than 75 years old. There were 62 (41.9%) male and 86 (58.1%) female, with a mean age of 76.9 (SD=7.1). Forty-nine patients (33.3%) received Comprehensive Social Security Allowance (CSSA). One hundred and eleven patients (75%) lived with family and 37 patients (25%) were either institutionalised or living alone. The reasons of referral to YFSGDH were: stroke (41.9%), hip fractures (20.3%), Parkinsonism (9.4%) and other causes (28.4%).

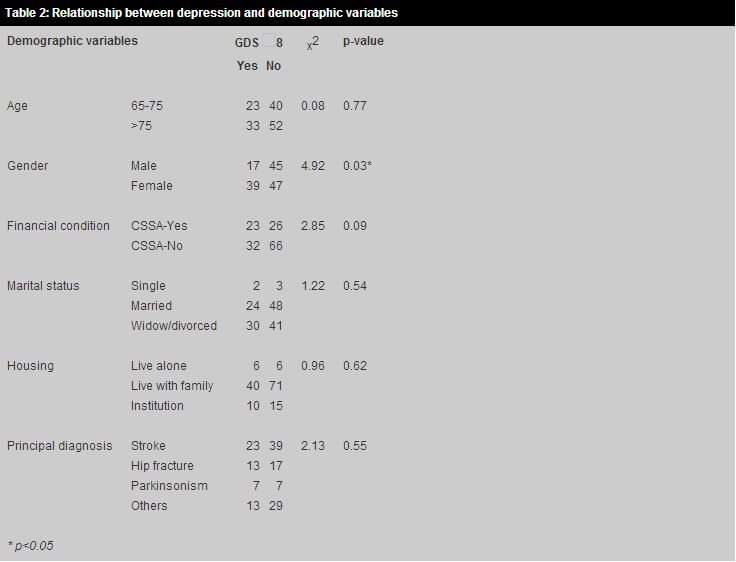

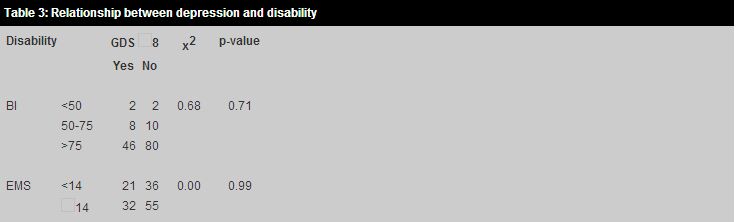

Prevalence of depression For GDS 8, there were 56 patients (37.8%). There were significantly more females having depressive symptoms (p=0.03), with 17 (27.4%) male and 39 (45.3%) female scoring GDS 8. There was a trend that depressive symptoms were more common in those patients who were on CSSA (p=0.09). There was no association between depression and other demographic variables: age, financial condition, marital status, housing and principal diagnosis, nor between depression and the level of disability (Tables 2 and 3s).

Discussion The GDS is widely used as a screening tool for depression. In this study, the 15-item Chinese version GDS was employed. It has been validated in Chinese populations with high sensitivity and specificity using a cut-off point of 8.14,15 It is useful in people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment.17 Subjects with moderate to severe cognitive impairment cannot answer many of the questions and were excluded from our study when their MMSE score was less than 15.13 Our study found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms of elderly patients in the geriatric day hospital was 37.8%, with 27.4% and 45.3% in male and female patients respectively. All these elderly patients were previously not diagnosed as having depressive illness. Studies have generated varied prevalence rates for depression among elderly populations. These range from 9% to 35%.3,18-20 In inner London, the prevalence of depression was found to be 18% in 1994.18 A recent study in a rural Malaysian community showed that 9% of elderly population with chronic illness had depression.19 In another study in a rural Chinese community, 26% of those aged 65 or above were screened positive for depression.20 A study of depressive symptoms in community geriatric population in Hong Kong by Woo et al in 1994 showed a similar prevalence rate as our study.3 The survey was carried out on a group of elderly Chinese aged 70 years and over selected by stratified random sampling from the registered list of all recipients of old age and disability allowance in Hong Kong. The screening tool was also the 15-item Chinese version GDS. The prevalence for this population was 29.2% for men and 41.1% for women. Comparison of prevalence among different populations is difficult, since the studies used different screening tools and diagnostic criteria. The age structures of different populations are also different. It might be expected that those with recent admissions to hospital for treatment of acute illnesses might have a higher rate of depressive symptoms than those without.11 However, this was not demonstrated in our study. We postulated that those who were very depressed might not turn up or simply refused to go to the geriatric day hospital for rehabilitation. Also, those patients with significant depressive symptoms might not be referred to the geriatric day hospital. This could be because their attending physicians perceived these patients as having poor motivation or rehabilitation potential. Similar to the local study,3 our study showed there were significantly more female patients having depressive symptoms than male patients. Though it was not statistically significant, there was a trend suggesting that depressive symptoms were more common in patients receiving CSSA. In this group of patients their financial constraints might have contributed to their depressive symptoms. In our study, functional disability did not predict depressive symptoms. Again, those with depression and severe functional disability might not be referred for rehabilitation in geriatric day hospital because of the perception of low rehabilitation potential by their attending physicians. Our study had its limitations. Firstly, there was potential bias in excluding those patients with a communication problem, psychiatric illness or cognitive impairment. For example, stroke patients usually have deficits in cognition and communication. Exclusion of this group of patients may under-estimate the true extent of depression. Secondly, our questionnaire was administered on admission. The GDS score may not truly reflect their depressive symptoms during their rehabilitation or on discharge. Depression may arise when patients perceive lack of progress during or after rehabilitation. Thirdly, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in YFSGDH cannot be generalised to other geriatric day hospitals or other rehabilitation settings. This is because different geriatric day hospitals may have different referral patterns. The GDS has a high sensitivity and specificity. It has a better performance than having house medical staff identifying depression.3 However, it is only a screening tool. It is definitely not a diagnostic instrument and the score of GDS does not predict the severity of depression. Any person who has GDS 8 cannot be labelled as depression yet unless a psychiatric interview supports and confirms the suspicion. GDS can be used to detect patients with depressive symptoms but it cannot replace our clinical assessment for accurate diagnosis of depression. Thorough clinical assessment is needed to guide the treatment plan. In our study, those patients screened with a score of GDS 8 were further evaluated by a physician for clinical diagnosis. Most of the patients (89%) with GDS 8 only needed counselling from paramedical staff. A minority of cases (11%) with depression needed antidepressant treatment or referral to a psychiatrist for further management. Further studies are needed to examine the effectiveness of screening for depression in the rehabilitation setting. Questions such as whether using GDS can increase the detection rate of depression or whether treatment of depression in depressed patients can reduce the rehabilitation time need to be further examined. Conclusion The World Health Organization estimates that depression will become the second most important cause of disability worldwide (after ischaemic heart disease) by 2020.11 Therefore, we should not overlook this problem. In our geriatric day hospital, a large number of patients have depressive symptoms. Female patients and those in poverty should, in particular, be carefully screened for depressive symptoms. Depression should be identified early and treated promptly so that it does not affect the rehabilitation process. Key messages

K W Wong, MBBS, FRACGP, FHKCFP, DCH

Medical Officer, D V K Chao, MBChB, MFM(Monash), FRCGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Family Medicine Cluster Coordinator (KE), Department of Family Medicine, United Christian Hospital. R Fung, MBBS, MRCP Medical Officer, P T Lam, MBChB, MRCP, FHKAM(Medicine) Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr K W Wong, HA Staff Clinic, Department of Family Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

|