|

December 2003, Volume 25, No. 12

|

Original Articles

|

Establishing the content validity in Hong Kong of the prioritised criteria of consultation competence in the Leicester Assessment Package (LAP)J K C Lau 柳坤忠, R C Fraser, C L K Lam 林露娟 HK Pract 2003;25:596-602 Summary

Objective: To test the content validity in Hong Kong of the prioritised

criteria of consultation competence in the Leicester Assessment Package (LAP).

Keywords: Validation, criteria of consultation competence, Leicester Assessment Package, Hong Kong. 摘要

目的: 評估李斯特評估準則(Leicester Assessment Package)有關診症能力的優先次序指標的內容是否適用於香港。

Introduction The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine (HKAM) was established in 1993 as a statutory body to regulate the standard of specialist training and practice in Hong Kong. Since 1993, registered doctors must be fellows of the HKAM to be listed in the Specialist Register of the Medical Council of Hong Kong. Family medicine was recognised as a specialty and the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP) became one of the foundation colleges of the HKAM. The examination requirements for HKAM fellowship in all specialties were standardised to include an intermediate examination after three to four years of basic training and an exit assessment at the end of two to three years of higher training. This has resulted in the extension of the previous four-year family medicine vocational training programme to six years and the introduction of a regulatory exit assessment (EA) to assure the standard of a specialist family physician. In 1997, the HKCFP held the first EA of its Higher Education Training Programme. One of the three components of the EA is a consultation skills assessment1 in which candidates engaged in consultation with a minimum of six unselected and consecutive patients in the doctor's own consulting room are directly observed by two College assessors. Performance is judged against the explicit and prioritised criteria of consultation competence as contained in the Leicester Assessment Package (LAP).2,3 The LAP was selected by the HKCFP because it was specifically designed for assessing consultation performance, its criteria for assessment were clearly defined to facilitate a more objective assessment and there were preliminary data available on its validity and reliability. The LAP is an integrated assessment tool which contains 7 prioritised categories of consultation competence and 39 components. It has been designed for both formative and regulatory purposes and can be used in both live and video-recorded consultations and with real or simulated patients. The LAP consultation categories and component competences have been demonstrated to be valid for general practice in the United Kingdom (UK).4 The LAP has also proved to be reliable, feasible and acceptable in a variety of situations: with simulated patients in an experimental situation,5 in regulatory assessments of general practice registrars in Kuwait,6 with established general practitioners in the UK7 and with medical undergraduates.8 Although the LAP has been successfully used as a tool for consultation skills assessment in the EA,1 its criteria of consultation competence have not been formally validated in the specific context of Hong Kong family medicine. Accordingly, we set out to test the content validity in Hong Kong of the prioritised criteria of consultation competence as contained in the LAP among family physicians. Methods A detailed questionnaire, modelled on the questionnaire used in the UK validation study, was sent to 489 full members of the HKCFP having a current mailing address in Hong Kong. These were doctors who had been predominantly engaged in family medicine for a minimum of three years (to include at least one year in Hong Kong), who had at least one higher qualification in family medicine recognised by the HKCFP and who had fulfilled three consecutive years of quality assurance before obtaining full member status. Those who fail to respond received postal reminders after two and five months. The questionnaire sought the views of the College members on the content validity of the seven categories of consultation competence and their 39 components. Opinions on the relative weightings of the different categories were also sought. Respondents were given the opportunity to respond to a series of statements or questions on a six-point scale (strongly approve, approve, tend to approve, tend to disapprove, disapprove, strongly disapprove). Respondents also had the opportunity to reject any of the proposed categories, components or weightings; suggest additional categories or components; state whether particular components should be re-allocated to other categories; give their opinion on the principle of prioritisation; and to propose amendments to the suggested weightings. Recipients of the questionnaire were also invited to provide some background demographic and professional information. Results There was a response rate of 57% with 279 questionnaires returned after three mailings. Almost three quarters (73%) of respondents were over 40 years of age, 52% were Fellows of the HKCFP, 32% were also Fellows of the HKAM, 22% were trainers and 11% were trainees in family medicine. Table 1 shows that 92% of respondents either strongly approved or approved of the overall set of LAP consultation categories and 82-97% either strongly approved or approved of the individual categories. Only 12 respondents (4.3%) wanted to exclude any categories. Although 50 respondents (17.9%) suggested a variety of new consultation categories such as communication skills (7 respondents), time management (4), continuity of care and evidence based care (3 each), there was no consensus among them.

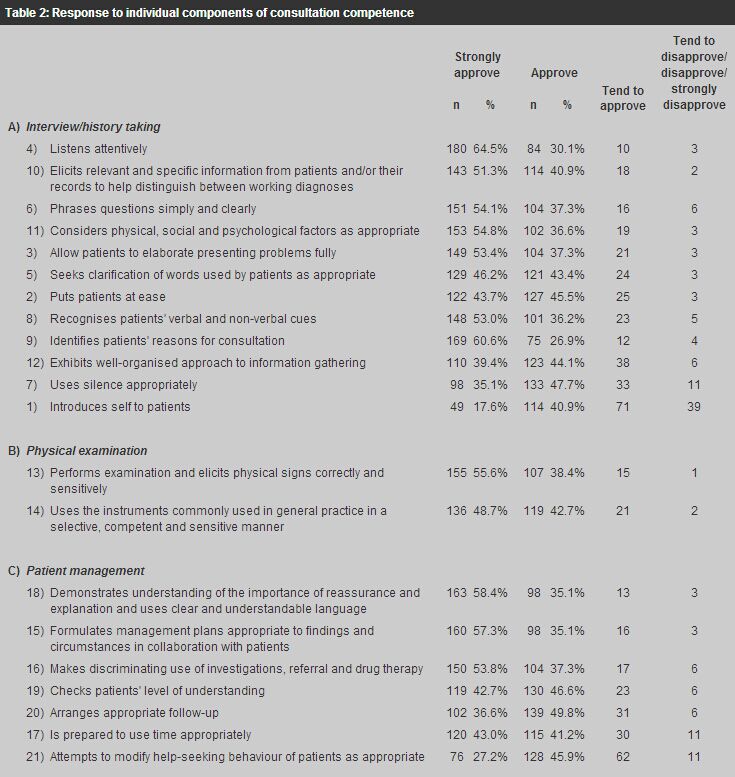

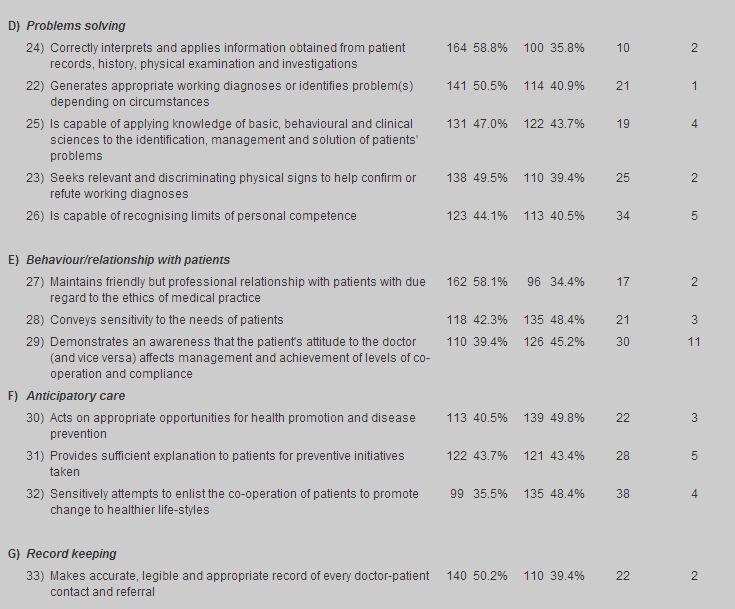

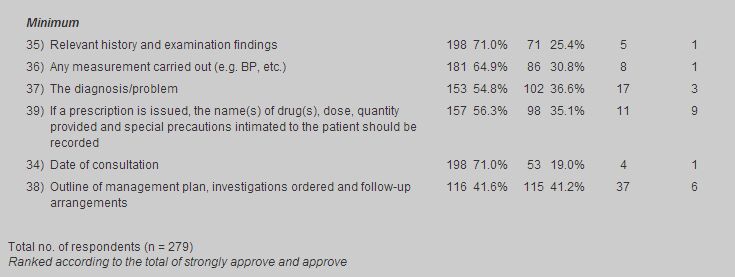

The responses to the 39 components of consultation competence are shown in Table 2. Twenty-one components were strongly approved or approved by 90-97% of respondents, 16 components by 80-90%, while "Introduces self to patients" received the lowest rating (59%). This latter component was also the only one to attract statistically significant differences in responses from trainers (72.1%), trainees (64.5%) and the remaining respondents (53%).

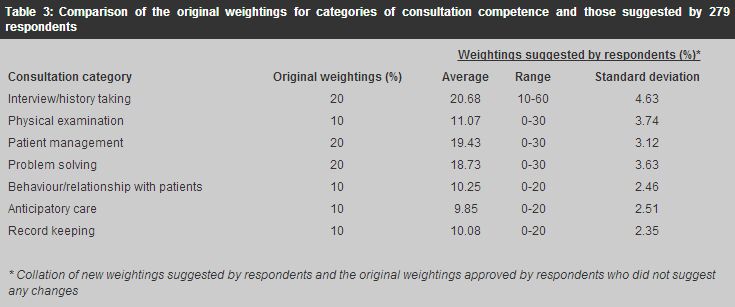

The differences between proportions of strongly approved or approved responses among three subgroups of respondents (trainer, trainee and neither according to their training status in family medicine) were not significant when they were compared together or by every two subgroups, except for component (1) "Introduces self to patients". There was a higher proportion of the trainer subgroup who strongly approved or approved of this component than the other two subgroups when they were compared together (X2=7.41, p=0.02 df=2). Only 9 respondents (3.2%) believed that any of the listed components should be shifted to another broad LAP category and only 23 respondents (8.2%) suggested additional components but with no clear consensus. When asked if they agreed with the statement "If consultation competence is to be formally assessed, some attempt must be made to identify relative priorities between any agreed categories of component consultation competence", 74% of the 260 respondents strongly approved or approved of such a principle. This increased to 93% when the tended to approve group was included. Only two respondents expressed strong disapproval of the statement. Concerning the suggested weightings of consultation categories, 65% of the 264 respondents strongly approved or approved while a further 23% tended to approve. Only three respondents strongly disapproved of the suggested weightings. Table 3 shows the high degree of agreement between the original weightings and those suggested by respondents. However, 81 respondents (29%) suggested alternatives when offered the opportunity to change the distribution of weightings between consultation categories. Fifty respondents (17.9%) suggested changes to the category of "Problem solving" while twenty-seven respondents (9.7%) suggested changes to "Record keeping". The other categories all had an average of forty respondents (~14%) who suggested changes to the weightings. Nevertheless, there was no consensus for change in the original weightings.

Discussion The above results demonstrate strong support in Hong Kong for the content validity of the seven categories and the 39 components of consultation competence as contained in the LAP and for the LAP weightings of consultation categories. Indeed, the responses of the Hong Kong doctors closely correlated with those of their UK counterparts.4 An overwhelming majority of respondents (92%) strongly approved/approved of the overall set of consultation categories and even the least supported individual consultation category (anticipatory care) was strongly approved or approved by 82% of respondents. There were also consistently high levels of support for 38 of the 39 individual components of consultation competence with no clear consensus to shift or to include any new components. The least approved component (as also in the UK study) was "Introduces self to patients" which was strongly approved or approved by only 59% of respondents (69% in the UK study). This was the only component competence, however, which produced statistically significant differences in approval for inclusion ratings in the respective responses from the sub-groups of trainers (72.1%), trainees (64.5%) and those who were neither (53%). This may partly be explained by the fact that the latter group of respondents (as in the UK study) were senior and experienced doctors who would already be known to their patients (and vice versa). On the other hand, it is surprising that only two-thirds of trainees recognised the importance of this component as they were the group of junior doctors who were most likely to be consulted by patients they did not know. We would support the continual inclusion of "Introduces self to patients" but stress that this consultation behaviour is only necessary when encountering a patient with whom the doctor is unfamiliar. The inclusion of weightings on the categories of consultation competence, a feature unique to the LAP, was approved in principle by 93% of respondents; and 88% of respondents expressed some degree of approval for the actual LAP weightings. While 29% of respondents suggested alternative weightings, high degrees of agreement were achieved between the original weightings and those put forward by the respondents (see Table 3). Consequently, we believe that the LAP weightings have been validated. The authors wish to emphasise that the scope of this study was limited to testing the content validity in Hong Kong of the explicit and prioritised criteria of consultation competence as contained in the LAP. It was not a study of all the types of validity of the LAP or of the reliability, feasibility, acceptability or educational impact of the LAP. Ideally, validity should be tested against a gold standard but this is not available for consultation competence. The only way to test such content validity is to determine whether an appropriate professional consensus exists. This is a standard method for assessing content validity of psychometric measures.9 A 57% response rate is comparable or even better than most other surveys among doctors in Hong Kong. Opinions may change but researchers can only test the here and now. Conclusion The criteria of consultation competence as contained in the LAP (7 categories and 39 components) have been field tested by exposure to the scrutiny of senior and experienced doctors in Hong Kong and found to achieve a high degree of content validity. Overwhelming support was demonstrated for the principle that whatever assessment procedure is used, some attempt must be made to identify the relative priorities between any agreed categories of consultation competence. Although a smaller proportion of respondents expressed approval of the suggested weightings, this however represents a high degree of consensus, as only a negligible proportion expressed outright opposition. Accordingly, the content validity of the prioritised criteria of consultation competence in the LAP has been established in Hong Kong, which strengthens its relevance as an assessment tool for both regulatory and summative purposes. Despite the differences in the funding systems and practice organisation between the two locations, the similar responses of doctors in Hong Kong and UK support the original conceptualisation of the LAP as a generic assessment tool that can be applied to consultations in widely different settings. It is hoped that by establishing the validity of explicit criteria of consultation competence in the context of Hong Kong, the awareness of the utility of the LAP in the assessment and improvement of consultation skills may be enhanced. As a result the standard of family medicine and patient care in Hong Kong may be improved. Key messages

J K C Lau, MBBS(NSW), FRNZCGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine)

Member, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. R C Fraser, CBE, MD, FRCGP, FHKCFP Professor of General Practice, University of Leicester, UK, Honorary Advisor, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. C L K Lam, MBBS, FRCGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Associate Professor, Family Medicine Unit, The University of Hong Kong, Honorary Advisor, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. Correspondence to : Dr J K C Lau, Research Committee, HKCFP, 7th Floor, HKAM Jockey Club Building, 99 Wong Chuk Hang Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|