|

December 2003, Volume 25, No. 12

|

Update Articles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Obesity - dietary management updateA W C Tang 鄧蕙菁 HK Pract 2003;25:616-622 Summary Dietary modification in weight reduction management is of vital importance. Whilst intensive promotion in the media of fad diets for weight loss is escalating, individuals fail to achieve long-term weight maintenance following the initial weight reduction. Conventional dietary management in conjunction with physical activity remains the best option for the individual who wants to achieve weight loss and maintenance, thus reducing risks of obesity-related co-morbidities. 摘要 減肥過程中,飲食調節至關重要。傳媒極力推廣的纖體餐,初期可以快速減重,但卻不能達到長期的效果。傳統飲食控制配合適當運動,仍然是減肥和保持適當體重的最佳方法,從而可以減低肥胖相關疾病的風險。 Introduction Obesity has become a global epidemic. New observations have concluded that in the past, most studies examining the effects of obesity on health were based on data from Europe or the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) report on obesity, prepared by the International Obesity Task Force, classifies obesity using the Body Mass Index (Table 1).1

People from the Asia-Pacific region are facing increasing health risks associated with obesity at lower Body Mass Index (BMI). In a study of Hong Kong Chinese, the risk of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and albuminuria starts to rise at a BMI of about 23,2 which is lower than the cut-off point currently recommended by WHO to define an increase in morbidity among Europids. Similar data from the Chinese in Singapore have been published.3 Based on risk factors and morbidities, WHO (Western Pacific Region) proposes different BMI ranges for the Asia-Pacific region (Table 1).4

Body fat distribution - waist circumference Fat distribution is just as important as body weight when determining the risks associated with obesity. The simple clinical measure is waist circumference (for visceral fat mass). Using waist circumference as an alternative classification system will provide a more sensitive measure of long-term health risks.5 One Dutch study found that men and women with measurements >102cm and >88cm respectively were associated with a substantially increased risk of metabolic complications.6 A recent WHO report suggested appropriate measurements in Europids to be <94cm for men and <80cm for women.1 However, values of <90cm for men and <80cm for women have been proposed as more suitable for the Asian populations. Reduction in waist circumference even with no weight change may result in significant reduction in obesity-related co-morbidities risk such as type 2 diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.4 Current recommendation is as follows (Table 2):

Waist-hip Ratio (WHR) is also used as a measure of abdominal obesity. In Caucasians, WHR >1.0 for men, and WHR >0.85 for women are indications of abdominal fat accumulation.7 However, waist circumference is still the preferred measurement of abdominal obesity over waist - hip ratio.1 Conventional dietary management Epidemiological studies showed that, within populations, those consuming diets with the highest proportion of fat and lowest proportion of carbohydrate are the most likely to become obese.8 A weight reducing diet prescription should take into account the following:

Specific dietary considerations Balanced diet Distribution of food intake should be as even as possible throughout the day, and meals should not be "skipped" as a weight control method. Although there is no direct association between eating frequency and the risk of obesity, a structured eating plan helps the individual to shop wisely and reduce the risk of unplanned eating episodes. The Food Guide Pyramid principle (Figure 1) provides healthy eating guidelines. The recommended nutrient distribution for weight reduction is as follows (Table 3):

Dietary fat Being the most energy-dense macronutrient, fat provides 9 kcal/g comparing to only 4 kcal/g for carbohydrate and protein. Hidden fat such as added oils, gravy/sauces should be taken into account. Fatty foods such as instant noodles, chips, chicken wings/feet, sausages, fish head and bone soup must be limited. A common misconception is canola oil is "less fattening" (i.e. has fewer calories) than peanut oil. The following (Table 4) shows the fat contents of fast foods from the same outlet:

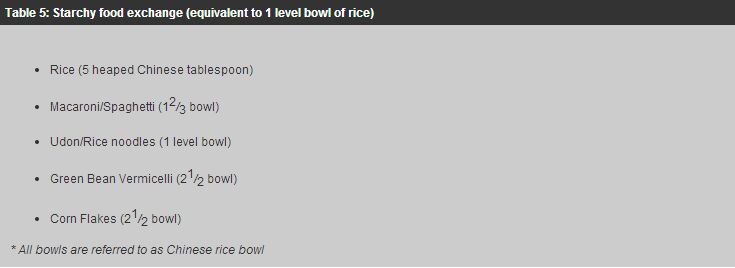

Dietary carbohydrate Starchy carbohydrates are still perceived as "fattening food" by many people especially for those who are trying to lose weight. This misconception must be clarified since carbohydrates actually have a low energy density comparing to fats. High carbohydrate foods such as rice, noodles, pasta, bread, cereals and potatoes provide the bulk of each meal as they help to increase our sense of satiety. They should account for 55-60% of total energy. Exchange systems are usually devised to ease compliance (Table 5). Fibre-rich sources such as red rice/wild rice, wholemeal pasta, bread and cereals also help to reduce risk of constipation when adequate fluid is also taken.

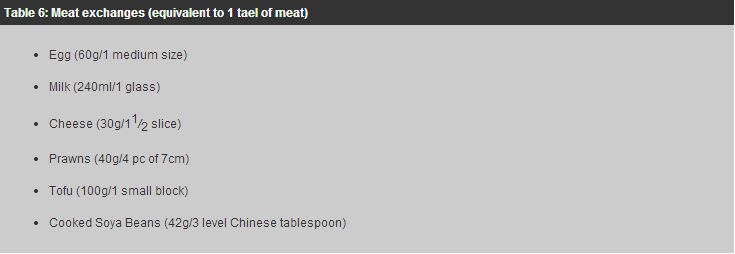

Dietary protein Protein intake should not exceed 15% of total energy but long-term deficiency of protein can result in muscle wasting including that of the heart, increased susceptibility to infection and fatty infiltration of the liver. High protein foods include meat, fish, eggs, tofu, milk, cheese and pulses. Excessive meat intake is also associated with higher fat consumption. For a 1500 kcal diet, meat portions may be approximately 5-6 taels per day (Table 6).

Fruits and vegetables Fruits and vegetables are good source of dietary fibre (non-starch polysaccharides), micronutrients and phytochemicals, which have a protective role on health. They together form a vital part in a balanced, reducing diet. Most vegetables (generally low energy density), especially leafy greens, provide bulk to a meal, thus promoting feelings of satiety. Intake of vegetables should be aimed at a minimum of 6 tael per day. Coconut and avocado have higher fat contents and should be limited. Daily intake of 2 portions of fruit is acceptable. Fruits tend to have a high sugar content. Misconception regarding the need to avoid banana should be clarified. The important concept is to prevent excessive/inadequate intake (Table 7).

Alcohol The UK Government's Inter-Departmental Working Group on Sensible Drinking formulated benchmarks for the general population on alcohol drinking: maximum daily intake should not exceed 3-4 units for men and 2-3 units for women (Table 8).13 Since alcohol provides 7 kcal/g, it should be abstained from or further cut down for those who want to lose weight.

Sugar-rich foods Cutting down on sugary foods and drinks will certainly help to control body weight, e.g. By cutting out one can of Cola/day (equivalent to 7 teaspoons of sugar)....

However, one can of soft drink or one piece of cake will not cause uncontrollable

weight gain. Excessive dietary restrictions run the risk of creating compensatory

cravings for these foods. Whilst total abstinence may sometimes be the best tactic

in those for whom certain foods trigger excessive consumption, for most individuals

it is important to learn how to control their intake of such foods in a rational

manner.

Fluid intake A daily intake of at least 2 litre of fluid (ideally plain water) is recommended. Drinking water before and after meals can also promote sense of fullness and will in turn help to reduce energy density of the meal. Common misconception: Chinese tea will help to lower fat absorption. Snacks Snacks may not be required by everyone. For some people, it may be genuine hunger; for others, taking snacks may be due to sheer boredom. For many people, it is probably best to include light snack between lunch and dinner in order to limit the chance of excessive hunger at dinner. Knowledge for appropriate food choices is important: for instance, a plain bun rather than a piece of cake; a glass of skimmed milk rather than a glass of sweetened lemon tea. The following (Table 9) shows that a fast-food meal can easily provide more than half of one day's energy need:

Sugar and fat substitutes Non-nutritive (intense) sweeteners e.g. Aspartame, Acesulfame Potassium, may be used. Although some do have energy value, their caloric contribution to food is negligible because they are used in such small quantities. On the other hand, fat-replacement foods such as "Olestra" are not generally available in the Asia Pacific region and have limited role.4 PracticalityPracticality Lack of practical skills (rather than lack of knowledge) is often the hindrance for following dietary regimens. Education for shopping, cooking, dining-out, food portions and exchanges are vital. Discussion on coping with social situations, how to decline food, etc is also useful. With intensive promotion in the media, the popularity of new and often bizarre approaches to weight reduction is escalating. The proposed diets which promise fast results with the minimum of effort often lead to low intake of macro- and micro-nutrients and the perpetuation of unscientific practices and substantial monetary loss. The potential health risks are seldom realised since fortunately these diets are usually abandoned after a few weeks. Variations of low carbohydrates, high protein/fat diets have been popular for many years. Protein and fat intakes were unlimited whilst carbohydrate intake was severely restricted. This could easily have led to excessive intake of fat (including saturates and cholesterol) when protein was obtained from animal sources. In addition, the initial rapid weight loss from diuresis was secondary to the carbohydrate restriction. Alternative weight loss products Caffeine Caffeine is a central nervous system stimulant that increases heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle stimulation. It has been used in many diet products to speed up metabolic processes. It can promote the burning up of fat as fuel during exercises. However, it has not been shown to lead to weight loss specifically. On the other hand, caffeine can cause dehydration, irritability, insomnia, headache and irregular heart beat. Chitosan Chitosan, as an ingredient in many weight-reducing commercial products, claims to inhibit dietary fat absorption by binding to lipids. Chitin is an indigestible fibre derived from the exoskeletons of shellfish. However, a recent study on humans reported no significant effects of chitosan on fat absorption; but chitosan may block the absorption of crucial fat-soluble vitamins such as the antioxidant vitamin E and increase calcium excretion.14,15 Study has shown that, chitosan in the administered dosage, without making changes to the diet, does not reduce body weight in overweight subjects.14 Very low calorie diets Very Low Calorie Diets (VLCDs) commonly supply about 400-800kcal per day. These are usually commercially produced nutritional preparations marketed for use as a total food substitute.

They are intended for use only with obese clients (BMI

Although VLCDs promote rapid weight reduction and may benefit certain individuals, such diets have health risks and should be undertaken only under medical supervision. This diet should be limited to 12-16 weeks duration to reduce the risk of adverse complications related to body protein losses, in particular cardiac problems. On completion of the VLCD programme, a gradual refeeding period of 2 to 4 weeks should follow. VLCDs appear to be safe and effective in promoting short-term weight loss and improvements in obesity-related co-morbidities. Perhaps the most serious issue against the use of VLCDs is the inability of the subjects to maintain their weight loss when regular food is reintroduced.18 For long-term maintenance of weight loss, they are considered to be no better than other methods of weight reduction.19 Wadden and Richman showed similar findings when administering standard energy-restricted diets in comparison with VLCDs.20,21 Certain hospitals in Hong Kong use a modification of this approach based on 3-4 drinks of the preparation (~400-550 Kcal) daily for 2 weeks; additional vitamin and mineral supplements are prescribed as required. Nutrition counselling by a registered dietitian is important during and after treatment to establish sound and long-lasting healthy eating habits and weight control. Physical activity Physical activity is a vital component of weight reduction therapy when used in conjunction with an energy-controlled diet plan. Increasing activity is most helpful in weight maintenance. Frequency, duration, and intensity of exercise can be gradually increased as tolerated by the obese individuals. Walking is almost always the most appropriate form of physical activity. An initial goal may be to walk 30 minutes/day for 3 days a week, building up to 45 minutes/day of more intense walking for at least 5 days/week. In addition, the "everyday" level of activity should be increased, such as taking the stairs instead of the elevator and walking short distances instead of driving or taking public transport. Even doing some household tasks instead of watching television can contribute to further increase in energy expenditure. Weight maintenance Studies conducted 2-3 years after treatment with VLCD and behavioural modification showed that those who exercised the most kept the most weight off.22,23 Losses of 5-10% of body weight are usually associated with significant improvements in health.24 Dietitian's continuing support during this phase is vital.25 Weight cycling The term "weight cycling" or "yo-yo dieting" refers to obese people who lose and then gain weight several to many times over their lifespan. Observations from the Framingham Study by Lissner have shown strong associations between weight variability and negative health outcomes.26 Both mortality and morbidity from coronary heart disease were increased in individuals with wider weight fluctuations. Using the data from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT), Blair also linked increased weight variability to the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.27 However, other studies have not shown the same results.28,29 Conclusion Conventional dietary management in conjunction with physical activity remains the best option for the individual to achieve weight loss and maintenance. Decrease in dietary fat and increase in fruit and vegetable and fibre consumption will help to reduce the risk of obesity and minimise the potential for the development of co-morbidities. The importance of physical activity should not be underestimated as it has been shown to be a key component in the prevention of weight gain. Key messages

A W C Tang, BSc(Hons), SRD(UK)

Registered Dietitian, Dietetic Department, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to : Ms A W C Tang, Dietetic Department, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

Bibliography

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||