|

February 2003, Volume 25, No. 2

|

Original Articles

|

"Tell me about your most loyal patients": Doctors' perceptions on factors affecting the doctor-patient relationshipA K Y Cheung 張潔影, C S Y Chan 陳兆儀 HK Pract 2003;25:52-58 Summary

Objective: To evaluate the quality of diabetic care in three primary

care clinics through collating data from clinical audit on the process of diabetic

management and glycaemic control.

Keywords: Diabetic care, audit, contro 摘要

目的: 通過對糖尿病管理過程和血糖控制進行臨床審核,分析有關數據,就 3 所基層醫療診所之糖尿病治療的質量做出評估。

Background Achieving good glycaemic control in diabetes mellitus is important. The Diabetes Control and Complications trial (DCCT 1993) proved that good glycaemic control in patients with Type 1 diabetes reduced the occurrence and progression of complications.1 The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 1998) found the same to be true for patients with Type 2 diabetes.2 For macrovascular complications, a subanalysis of the Framingham Heart Study cohort has demonstrated a dose-response association between glycosylated haemoglobin levels and the prevalence of cardio-vascular disease.3 The role of general practitioners in diabetic care is clear and beyond doubt.4 However, the level of performance in primary care is variable.5 General practitioners often do not follow international recommendations.6 Some patients received part of the care recommended by guidelines7 and some remained in poor glycaemic control. Evidence about both process and outcome is needed to ensure the quality of primary care for diabetic patients. Diabetes mellitus is a major health problem. According to the Hong Kong Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study (Janus 1995), among both men and women aged 25-74, about 1 in 10 had diabetes mellitus. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in men increased from 2% at age 25-34 to 21.7% in those aged 65-74. In women the corresponding prevalences were 1.4% and 29.3%.8 There are three families clinics of the Department of Health. They are located at Wan Chai, Chai Wan and Yau Ma Tei to provide primary care to civil servants, their dependants and pensioners. The authors wish to evaluate the components of diabetic care and the treatment goals in the families clinics, and implement interventions to achieve improvement through audit.9 Medical audit is a process for critical analysis of medical practice, to improve the quality of routine medical care provided for patients.10 Marshall Marinker defined audit as the attempt to improve the quality of medical care by measuring the performance of those providing the care, by considering the performance in relation to the desired standards, and by improving on this performance.11 Objectives

Method A complete list of diabetic registry in each clinic was obtained, either from the computer system or manual registry. All medical records of diabetic patients regularly followed up in the three clinics during the study period were reviewed. The first data collection in early 2000 was a retrospective record review of diabetic patients actively attending the clinics during the period 1/1/1999 to 31/12/1999. Patients registered as diabetes mellitus were identified and the correct diagnosis was reviewed. Fasting plasma glucose cut-off value of 7.8mmol was used for patients with chronic diabetic history.14 Patients under regular specialist care were not included. Eight hundred and eleven records were retrieved, four actually had impaired fasting glucose and 807 patients met the inclusion criteria. This audit reviewed both clinical performance and outcome of diabetic care. For process measurement, the criteria of Monitoring Diabetes of the Eli Lilly National Clinical Audit Centre were adopted. Compliance was measured for having a diabetic registry, correct diagnosis, assessment of smoking habit, checking for urine albumin, blood pressure, feet examination, fundi examination, checking for HbA1c, review of diet, body weight check, review of hypoglycaemic attacks, checking for patient monitoring technique and home monitor records, performance of visual acuity, regular provision of follow-up, recording of complications and checking of blood lipids.12 For outcome glycaemic control, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) standards of medical care for patients with Diabetes Mellitus were adopted. The goal was glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) <7%, additional action suggested when >8%.13 The first audit results were presented in the clinic meeting within each clinic. Doctors and nurses showed awareness for the need to improve. Further meetings amongst change facilitators from each clinic were held to adopt improvement suggestions. The second data collection was performed one year after implementation of changes during late 2001. Records of diabetic patients actively attending the clinics during 1/9/2000 to 31/8/2001 were reviewed. With the revised recommendations from WHO, the diagnostic criteria of fasting plasma glucose of 7mmol/l was adopted for new patients.14 Nine hundred and seventy seven records were retrieved, 2 had impaired fasting glucose and 975 patients met the inclusion criteria. Results (a) Patients characteristics There were 801 and 975 records reviewed in the first and second phases respectively. In both phases, nearly all (>99%) were suffering from non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. One quarter of patients required diet treatment only. The results were summarised in Table 1.

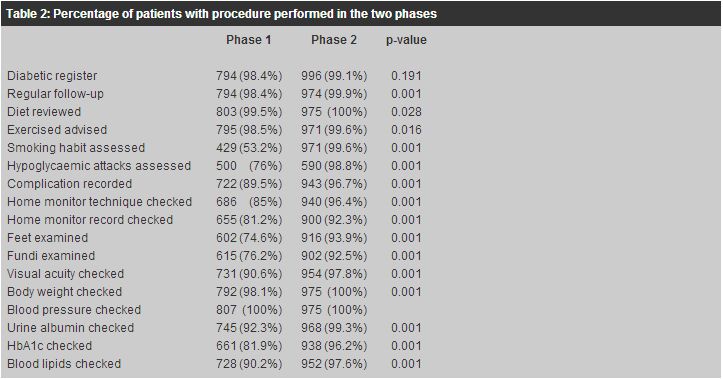

(b) Process performance The results of the two phases were compared and summarised in Table 2. There were improvements in all criteria.

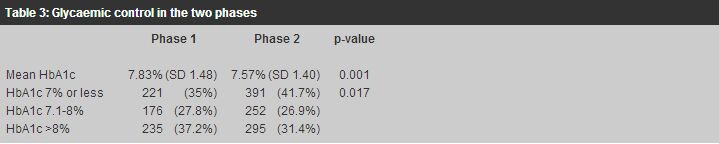

(c) Glycaemic control (Table 3) Mean HbA1c lowered from 7.83% (SD 1.48) to 7.57% (SD 1.40) (p=0.001). Patients with satisfactory HbA1c7% increased from 35% to 41.7%, whereas patients with unsatisfactory HbA1c >8% lowered from 37.2% to 31.4% (p=0.017). The results were summarised in Table 3.

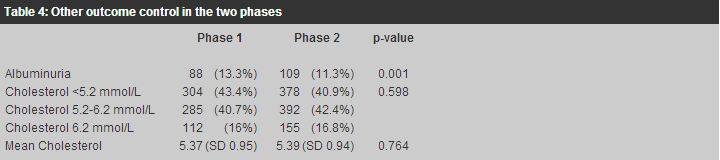

(d) Other outcome Other outcome results of the two phases were shown in Table 4. Slightly more than one quarter of patients maintained normal blood pressure. Over 10% of patients had albuminuria. About 40% patients had normal total cholesterol. The mean cholesterol was around 5.3mmol/L.

Statistical methods The results of the two audit phases were compared and analysed by SPSS. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Independent t-test was used for numerical variables. Paired t-test is not used because subjects in the two phases were not identical. However, there is overlap in the subjects in the two phases. Separate analyses for paired and unpaired subjects were not done. Discussion The adherence to diabetic guidelines in general practice was variable. Faruqi assessed the attitudes to the use of guidelines for the clinical management of diabetes mellitus in general practice, and found that many respondents were not aware of the guidelines, and 13 out of the 31 diabetic projects reported the use of guidelines.15 Weiner reported that the compliance to guideline in management of elderly diabetic patients was low, 85% did not have the recommended HbA1c measured, and 45% did not have cholesterol measured.6 In our primary care clinics, diabetic patients were managed according to diabetes a protocol developed by the Department of Health. Data on process and outcome were entered into a computer software programme for general outpatient clinics.16 We emphasised the compliance to procedures recommended with a higher level of evidence.12 During the audit period, difficulties in adhering to the protocol were identified and solutions sought out. In this study, patients under regular care of the same doctors had most procedures done, while some patients who had to attend different doctors in the follow-up consultation were more likely to have procedures outstanding. There were frequent change of doctors during the year in some consultation rooms. This may affect the adherence to the clinic's diabetic guideline. To tackle this problem, written guidelines were given to all doctors including new arrivals. Doctors were reminded about the protocol during periodic record review sessions and clinic meetings. The use of a coloured annual assessment flow chart in the first page of the medical record served as a reminder. Computer reminders were also used for patients with data outstanding. These combined efforts aided compliance with the clinic protocol and we were able to obtain improvements in all process measurements. The quality of diabetic care, as reflected in the process performance, varied among practices. In 1996 Dunn17 performed audit in 37 UK practices with 3974 patients. Notes were reviewed, 44% had eyes examined, 25% had cholesterol checked, 50% smoking status checked, feet examined in 57%, glycaemic control and blood pressure measured in 75% of patients. We compared the results of this audit to diabetic audit in the General Practice Unit of the University of Hong Kong by Lam 1992,18 which had already achieved good results. There were 140 diabetic patients reviewed in Lam's audit, feet examination 77.9% (ours 93.9%), fundi examination 59.3% (ours 92.5%), urine albumin checked 78.6% (ours 99.3%), glycosylated haemoglobin checked 65.7% (ours 96.2%), blood pressure checked 99.5% (ours 100%). Overall, the process performance was good in our three clinics. Concerning glycaemic control, according to the ADA 2002, average HbA1c7% (1% above the upper limits of normal) were associated with fewer long-term microvascular complications, while more than 8% is associated with a higher risk of complications.13 In the UKPDS study, 3867 patients newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus were randomised to the intensive group and the conventional group. Over 10 years, HbA1c was 7% in the intensive group compared with 7.9% in the conventional group.2 In Dunn's audit,17 mean HbA1c was 8.07%. A randomised controlled study with 6 years follow-up on type 2 diabetic patients by Olivarius et al in 2000, involving 311 Danish practices with 474 general practitioners, median HbA1c was 8.5% in the intervention group who received structured care with regular evaluation, and 9% in the comparison group who received routine care in ordinary consultations, where doctors were free to choose any treatment and change.19 We had 41.7% patients with HbA1c7%, with overall mean 7.57%. Nearly one-third of patients had HbA1c >8%. There is room for further improvement. Future cohort study on the glycaemic control will be useful to better reflect glycaemic control. For microvascular complications, it has been shown that intensive normoglycaemic control delays the onset of microalbuminuria and the progression to albuminuria in both type 1 and 2 diabetic patients. Nephropathy developed in 20-30% patients.13 The use of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) provides a selective benefit over other antihypertensive agents in delaying the progression of microalbuminuria to albuminuria.13 At the time of the audit, patients were screened for albuminuria. From June 2000, the three clinics included microalbuminuria screening into the diabetic protocol. It would be meaningful to evaluate the use of ACEI and the development and progression of microalbuminuria and albuminuria, in future studies. In Hong Kong, the prevalence of retinopathy and neuropathy for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus was estimated to be 22% and 13% respectively.20 The three clinics had retino-photography support, and patients had either intinal-photographs taken or fundi examination by ophthalmoscope. However, the rates of retinopathy and neuropathy were not reviewed in this audit. For cardiovascular complications, the UKPDS has demonstrated that rigorous blood pressure control reduces the risk of both macrovascular and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, even more so than the effect of strict glycaemic control,21 in which an upper limit of 150/85mmHg was used. According to ADA, diabetic patients with systolic blood pressure not exceeding 130mmHg and diastolic blood pressure not exceeding 80mmHg was associated with reduced cardiovascular risk.13 In this audit, around 30% of patients had a blood pressure of 130/80mmHg or below. There is definite room for improvement. Lipid management aimed at lowering LDL cholesterol, raising HDL cholesterol and lowering triglycerides has been shown to reduce macrovascular disease and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.13 It would be useful to evaluate the management of dyslipidemia and the development of cardiovascular complications. Objective evidence of lifestyle changes such as weight control, increased physical exercise, and smoking cessation, which are potentially beneficial in preventing coronary heart disease, would be meaningful in future studies. Limitation This is an audit study in which no control group is used. Thus, the changes observed may reflect a change in practice of the doctors or medical system rather than the intervention. Conclusion Audit is not fault finding. It was through this audit that clinic staff realised the objective evidence of quality of care provided. The exercise also facilitated staff to identify the deficiencies of the clinic and to find methods to tackle. The multi-practice audit reflected the objective evidence of quality of diabetic care in the three primary care clinics. Measuring the process performance, results showed much improvement and had met the standards. However, outcome measurements would be of utmost importance. Sixty percent of patients required more stringent glycaemic control. Blood pressure, lipid control and development of complications were not initially addressed for comparison in this audit. Future study should emphasise on the outcome measurements and aim at optimal control. Acknowledgement We would like to give our sincere thanks to Richard Baker and Kamlesh Khunti for their advice and support throughout the audit cycle. All clinic staff are highly appreciated for their participation and help in data collection and input. We thank Dr Luke Tsang, Consultant in Family Medicine, for his support in the writing up. We also like to thank the Department of Health for the approval in publication. Key messages

C Y M Fan, FHKAM(Family Medicine), Specialist in Family Medicine

Senior Medical Officer, i/c, L C Choy, MRCP(UK), FHKCFP, FRACGP Senior Medical Officer, K W Ho, DFM(CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP Medical & Health Officer, Chai Wan Families Clinic, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. K B Tsui, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Senior Medical Officer, Hong Kong Families Clinic, Tang Chi Ngong Specialist Clinic. K H Kwok, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Senior Medical Officer, Kowloon Families Clinic, Yau Ma Tei Jockey Club Polyclinic. W M Pau, MRCGP(UK), FHKAM(Family Medicine), Specialist in Family Medicine Senior Medical Officer, Family Medicine Clinic, St. John Hospital, Cheung Chau. Correspondence to : Dr C Y M Fan, Chai Wan Families Clinic, 1/F, Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong.

References

|

|