|

February 2003, Volume 25, No. 2

|

Update Articles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early detection of visual lossJ S M Lai 黎少明 HK Pract 2003;25:70-77 Summary A logical and organised approach to the symptoms of patients with eye disorders is the key to diagnosis and proper management. This article reviews structured approach to patients with visual impairment, ocular pain and change in the external appearance and considers the wide differential diagnosis. It focuses specifically on the evaluation of patients with the 3 common ocular symptoms, and visual loss resulting from cataract, glaucoma, uveitis, diabetic retinopathy, macular diseases, central retinal artery occlusion, retinal detachment, optic neuritis and ischaemic optic neuropathy. 摘要 合理有序的處理症狀是正確診斷和治療眼病病人的關鍵。本文回顧了視力障礙、 眼痛和眼外觀異常的病人的處理方法和各種鑒別診斷。作者重點論述如何評估以上三種常見眼科症狀的病人, 並述了可能導致視覺喪失的常見眼疾,包括白內障、青光眼、眼葡萄膜炎、糖尿病性視網膜病、黃斑病、 視網膜中央動脈堵塞、視網膜脫落、視神經炎和缺血性視神經病。 Introduction Many blinding eye diseases are treatable if diagnosed early. It is therefore important to detect early visual symptoms that may signify a serious eye disease so that appropriate treatment can be given before irreversible damage has occurred. Although most severe eye diseases ultimately require intervention by an ophthalmologist, the primary care physician can play a major role in diagnosing and preventing many blinding eye disorders. Appropriate referral requires knowledge of the early symptoms, and signs of these diseases and is critical to visual outcome. In the first part, this article discusses the 3 main common ocular symptoms, and in the second part some of the non-traumatic causes of visual impairment in Hong Kong. Ophthalmic symptoms Patients with ophthalmic problems usually complain of the following 3 symptoms either alone or in combination: visual impairment, ocular pain or discomfort and change in external appearance. To form a clear, undistorted and 3-dimensional image in our brain from a seen object, we need to have proper alignment of both eyes' visual axis, normal refraction power of the cornea and the lens, transparent media in the visual pathway, normal rods and cones functionally and anatomically, normal optic nerve and visual cortex. Visual impairment can occur when any of the above structures is abnormal.

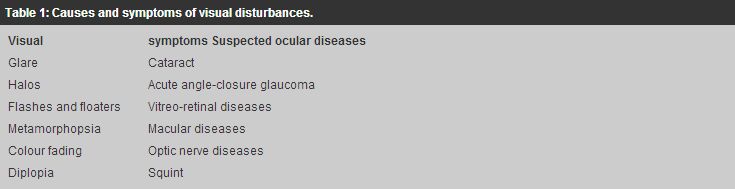

Visual impairment can range from minor visual disturbance to actual visual loss. Symptoms of visual disturbance include glare which may occur in cataract when light is scattered by the opacities in the lens;1 halos which may occur in acute angle-closure glaucoma when light is dispersed into different colours by the oedematous cornea (Figure 1); flashes and floaters which may occur in vitreo-retinal diseases when there is vitreous traction on the retina and opacities in the vitreous;2 micropsia (seeing diminished objects) metamorphopsia (seeing bending of lines) which may occur in macular diseases when the photoreceptors in the macula area are deranged anatomically;3 colour fading which may occur in optic nerve diseases;4 diplopia which may occur in squint (Table 1).

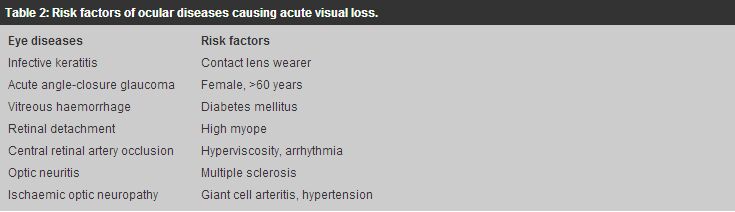

Visual loss can be near or/and distant, central or/and peripheral. Refractive error can affect preferentially distant or near vision. For example, myopia affects mainly distant vision whereas presbyopia affects near vision. Visual impairment due to refractive error can generally be improved when patients see through a pinhole. On the other hand, ocular pathology like cataract usually affects both distant and near vision and the visual impairment is usually not improved with a pinhole. Central vision is tested using the standard Snellen chart and peripheral vision is assessed by visual field tests. Pathologies involving the macula affect the central vision early whereas diseases of the peripheral retina may not impair the central vision until late. Chronic glaucoma typically affects the peripheral field of vision in the early stage of the disease. The finding of central or peripheral visual loss may signify an on-going ocular disease and warrants further investigations. Visual loss can be acute, progressive and acute on chronic. Some of the causes of acute visual loss are infective keratitis, acute iritis, acute angle-closure glaucoma, vitreous haemorrhage, retinal detachment, central retinal artery occlusion, optic neuritis and ischaemic optic neuropathy. Some patients are at higher risk of developing the above eye diseases (Table 2). Progressive or chronic visual loss is most commonly due to cataract. However, a mature cataract complicated by phacomorphic (lens induced) glaucoma may present with acute on chronic visual loss.5

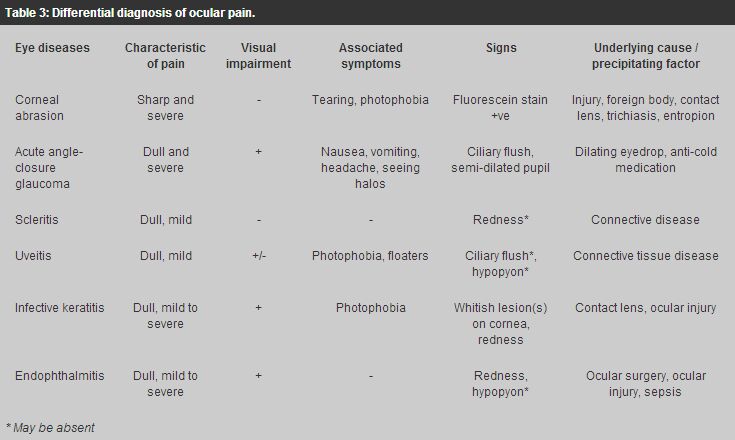

Ocular pain Ocular pain can be sharp and/or dull aching. Sharp and severe ocular pain signifies pathology in the cornea. In corneal abrasion where the corneal epithelium is ablated and the nerve endings are exposed, the patient complains of severe, sharp ocular pain, excessive tearing and photophobia. This can be caused by mechanical injury from fingers, hard objects, eyelashes in trichiasis (posterior misdirection of lashes), eyelid in entropion (in-turning of eyelid). The pain is so severe that the patient will squeeze the eyelid and ocular examination may be impossible. Fortunately, the corneal epithelium regenerates rapidly and the denuded area usually heals in 1-2 days. Treatment with topical eye ointment is enough.6-8 However, if the epithelial defect fails to heal in a few days, an underlying cause or ocular infection should be suspected. Table 3 summarises the different causes of ocular pain.

Dull aching pain occurs in ocular infection and inflammatory diseases e.g. infective keratitis, endophthalmitis, scleritis, uveitis. It is stressed that ocular pain is usually absent in most of the chronic types of glaucoma in which the intraocular pressure (IOP) is progressively elevated. Severe ocular pain is only present in acute angle-closure glaucoma when the IOP markedly increases within a very short period of time. Change in external appearance Change in external appearance This refers to eyelid conditions like exophthalmos, ptosis (dropping of eyelid), entropion, ectropion (out-turning of eyelid) and ocular conditions like red eyes, leukocoria (white pupil) and squint. Apart form cosmetic reasons, corneal complication is the common indication for surgical correction in eyelid diseases. Red eyes are commonly due to conjunctivitis especially viral in origin. However, when there is pain or associated loss of sight, or conjunctivitis that does not respond quickly to treatment, causes other than conjunctivitis like ocular, intraocular, orbital infection and inflammation should be suspected. Leukocoria in a child needs careful examination (Figure 2). Pupillary dilation can enhance the ability of the examiner to detect leukocoria.8 Retinoblastoma (Figure 3) and congenital cataract can both give rise to a white pupil with or without co-existing squint.9 Early diagnosis and treatment is the only way to save the child's life and vision and referral of the child to an ophthal-mologists is crucial in the management of leukocoria. The management of a child with squint requires a team-approach. The team consists of an ophthalmologist, orthoptist and optometrist who will assess the type and degree of the squint, rule out organic cause especially retinoblastoma, treat amblyopia if present, decide on surgery for re-alignment of the visual axis.

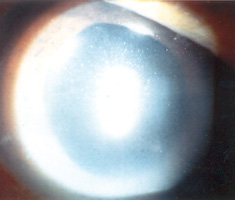

Cataract Senile cataract is the most common cause of visual impairment in the elderly population. Patients experience glare and/or change in the refractive status in the early stage of the disease depending on the morphology of the cataract. As the density of the cataract increases, the vision becomes progressively blurred. When the visual disability interferes significantly with the patient's daily activities, cataract extraction with implantation of an intraocular lens is indicated. When the cataract becomes mature, the patient will carry a risk of developing lens induced uveitis and/or angle-closure glaucoma.10,11 Microbial keratitis Microbial keratitis, infection of the cornea by micro-organisms, is a serious complication associated with contact lens wear. Micro-organisms probably adhere to the contact lens, transfer from the contact lens to a damaged or compromised corneal epithelial surface, penetrate into the deeper layers of the cornea and produce corneal damage. Host responses to the invading micro-organisms, while designed to protect the eye, can often exacerbate the situation and the resulting microbial keratitis can lead to permanent blindness. Patients suffering from microbial keratitis complain of decreased vision, redness, eye pain and photophobia. Whitish infective lesion may be seen on the cornea and pus may be seen in the anterior chamber (hypopyon). Urgent microbial work-up including corneal scraping and contact lens solution culture, appropriate anti-microbial agents are important in the management. Empirical topical antibiotics should cover both gram positive (e.g. Staph. Aureus) and gram negative (e.g. Pseudomonas aeruginosa) organisms. This includes gentamicin or tobramycin and ciprofloxacin (fortified drops preferred). The cornea may perforate or may scar excessively requiring corneal transplantation.12,13 Glaucoma Glaucoma is one of the most common preventable causes of visual loss. It is a group of diseases leading to damage of the optic nerve head with characteristic optic disc cupping and progressive visual field loss. The exact mechanism of damage is unknown, but current research is pointing toward a multifactorial disease process, in which elevated IOP is just one of the factors.14-16 There are at least 2 major types of glaucoma, open angle and angle closure. Angle-closure glaucoma can present insidiously like open-angle glaucoma and can also present as acute attack with prominent symptoms and signs. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is an asymptomatic condition until late in the process. Primary care physicians rarely test their patients for this type of glaucoma, primarily because of the lack of specificity or sensitivity of any one particular test. Direct ophthalmoscopy proved to be the most valuable single test in diagnosing glaucoma and the combination of measurement of IOP and direct ophthalmoscopy was shown to be the most likely method of diagnosing glaucoma or identifying glaucoma suspects.17 Acute angle-closure glaucoma is a specific type of glaucoma characterised by sudden increase in the IOP. Patients complain of acute visual loss, ocular pain, headache with nausea and/or vomiting. Examination reveals ciliary flush (redness around limbus), corneal oedema and a semi-dilated pupil in the attacked eye. Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) is an eye emergency requiring immediate treatment to lower the IOP. Immediate treatment includes the use of systemic acetazolamide (250 - 500mg intravenous or oral stat dose) to suppress the aqueous production and pilocarpine eyedrop to constrict the pupil. Primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) which is more common in Asians can develop silently like POAG without going through the highly symptomatic stage of AACG (Figure 4).

Uveitis The cause is usually idiopathic and may be associated with connective tissue diseases. In anterior uveitis (iritis), there are inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber and keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelial surface (Figure 5). Hypopyon may also be present. The redness is distributed around the limbus (ciliary flush). The main symptoms include decreased vision, redness, dull ocular pain, tearing and photophobia. In posterior uveitis, there are inflammatory cells in the vitreous. Depending on the site of involvement, symptoms may vary from seeing floaters only to impairment of vision. The optic disc and the macula may be oedematous. There may be exudative retinal detachment. Treatment is by topical steroid. In severe cases, systemic steroid or even immunosuppressant may be required. Severe uveitis can result in keratopathy, cataract and secondary glaucoma (Figure 6).18

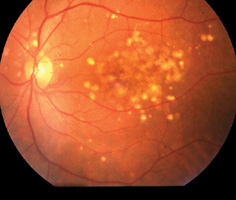

Diabetic retinopathy Patients with diabetes are at risk for multiple visual complications, most notably diabetic retinopathy. In non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, microvascular damage from diabetes leads to microaneurysms, haemorrhages, exudates, and cotton-wool spots. Patients are usually aymptomatic at this stage. Further progression into the proliferative stage leads to new vessel growth, or neovascularisation, on the retina and the iris. Growth of new blood vessels can cause severe haemorrhage in the vitreous cavity (vitreous haemorrhage) and the anterior chamber (hyphaema), tractional retinal detachment and neovascular glaucoma, and permanent visual loss. However, when there is macular oedema, vision can be impaired at the non-proliferative stage. Laser photocoagulation is indicated to prevent further deterioration of the vision. In countries where ocular complications of diabetes have been managed on the basis of well-codified protocols, the incidence of visual loss has been significantly reduced. In other areas large numbers of diabetic patients still experience visual loss due to retinal complications of the disease.19,20 Diabetic retinopathy is a preventable blinding disease. If patients are treated with laser photocoagulation in the early stage, the disease can be prevented from advancing to the proliferative stage which often requires complicated vitreo-retinal surgery. Patients with diabetic mellitus should have a thorough eye examination at least once a year. Referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary when diabetic retinopathy is found and urgent referral is needed when there is acute visual loss or further deterioration of the impaired vision. Macular diseases The macula is the most important structure in the retina responsible for central vision. Any pathology that results in disturbance in the cellular function or the anatomy of the macula will cause a disturbance in the central vision. Some of the pathologies that affect the macula include central serous retinopathy (CSR) and age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). CSR usually occurs in young male adults (Figure 7). Fluid leaks out from the choriocapillaries. Patients commonly complain of micropsia and metamorphopsia. This phenomenon is due to disturbance of the alignment of the rods and cones by the fluid in the subretinal space. Most of the cases resolve spontaneously but may recur.21 Laser treatment is useful in selected cases.22 ARMD, a disease of the aged, can manifest from its early stage of drusen formation to sub-retinal neovascular membrane (SRNVM) haemorrhage and finally to macular scar (Figure 8a,8b,8c). Patients in the early phase of age-related maculopathy may have scotopic dysfunction including difficulty in night driving, near vision tasks and glare disability.23 Symptom of metamorphopsia may signify the onset of SRNVM. Some types of SRNVM are treatable with photodynamic therapy.24 Unfortunately, in many of the macular diseases low visual aids may be the only mode of treatment.

Central retinal artery occlusion Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) occurs most commonly between the ages of 50 and 70 years, and nearly one-half (45%) of patients also have carotid artery disease.25 This is commonly due to blockage of the central retinal artery by an embolus. There is acute visual loss. Although no specific treatment is available at present, the patient should be referred urgently to ophthalmologist. Non-specific treatments including paper bag breathing to induce vasodilation from hypercapnia, lowering of the intraocular pressure by medications or anterior chamber tapping to release some of the aqueous are usually initiated.26 The prognosis of CRAO is in general poor. Most importantly is to have a thorough medical assessment for underlying life-threatening cardiovascular diseases. Retinal detachment Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment refers to detachment as a result of a retinal break. High myopic patients are at higher risk of developing retinal detachment than the general population.27 The presence of a retinal break can be asymptomatic, or can present with floaters and flashes.28,29 In the presence of retinal detachment, there may be localised visual field defect. When the macula is involved, the central vision is affected. Treatment of retinal detachment is by surgery. Tractional retinal detachment refers to detachment as a result of the pulling force from fibrous tissue traction on the retina. This is seen in advanced stage of proliferative diabetic retinopathy.20 Ischaemic optic neuropathy This occurs in the elderly patients who present initially with acute and profound visual loss and optic disc oedema which progresses to optic atrophy in a few months.30 Patients may have an altitudinal visual field defect (field defect that crosses the midline). Ischaemic optic neuropathy (ION) can be idiopathic or can be caused by giant cell arteritis (GCA) which gives rise to symptoms including malaise, fever, weight loss, headache, muscle aches, jaw claudication and scalp tenderness over the temporal arteries.31 The optic disc looks pale and swollen. The ESR is markedly raised. Systemic steroid is given once the diagnosis is confirmed histologically by temporal artery biopsy.32 Optic Neuritis Optic neuritis is an acute demyelinating event affecting the optic nerve. It is typified by sudden onset of visual impairment and pain with eye movements, followed by spontaneous recovery of vision to normal or near normal over several weeks.33 It is often associated with multiple sclerosis as the first clinical manifestation of the disease.34 Clinical findings include diminished central visual acuity and colour sensation ('washed-out' coloured objects), decreased contrast sensitivity, and visual field abnormalities.4 An afferent pupillary defect is often present.35 Depending on the site of the inflammation, optic disc oedema may be seen if the optic nerve head is involved. Treatment with high dose systemic steroid hastens the recovery but does not affect the final visual outcome.36 Conclusion Many blinding eye diseases have characteristic symptoms and signs in their early presentations. If primary care physicians are alert to these symptoms and signs, immediate first-line treatment can be initiated and appropriate referral can be made and the blinding eye diseases may hopefully be controlled. Key messages

J S M Lai, MBBS, FRCOphth

Consultant, Department of Ophthalmology, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr J S M Lai, Department of Ophthalmology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||