|

February 2003, Volume 25, No. 2

|

Update Articles

|

Diagnosis and management of stress-related psychiatric disorders in primary careK Y Mak 麥基恩 HK Pract 2003;25:78-84 Summary Stress is a universal phenomenon. Vulnerable persons exposed to excessive stress can, however, develop a variety of psychiatric disorders. There are three specific disorders in psychiatry that are clearly stress-related: acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Each type is described in some detail in order to facilitate prompt diagnosis. Management by the primary care physician is described. 摘要 生活中普遍存在壓力,但對於脆弱的人來說,壓力過大會導致各種各樣的精神疾病。 精神病學中有三種疾病與壓力有明確關係,即急性應激障礙,適應障礙和創傷後應激障礙。 本文對這三種疾病都進行了較詳細的描述,以幫助醫生及時做出診斷,並介紹適合基層醫生使用的治療方法。 Introduction The term "stress" is a very confusing one that can mean different things to different people. For example, to a physics student the term means weight over area, while to the weather reporter it means atmospheric pressure. Indeed, the Chinese word for stress, "ya li", also means pressure. Engel1 concluded that "stress is neither a noun, nor a verb, nor an adjective. It is an escape from reality". The English word comes from the Middle English word "distress" which was derived from the Old French word "destresse", meaning "placed under oppression". In other words, when ones feels oppressed one is stressed. The concept of stress and stressors Selye2 coined the word "stressor" to refer to sources of potential stress, and Fontana3 distinguished "stress" from "stressors" using the following definitions:

"Stressors" can be internal or external, acute or chronic, actual or perceived, and include physical, psychological and psychosocial stimuli. Using the stimulus-response model, there are three types of stress, viz.:

focus on stimuli or situations that typically disturb or disrupt the individual e.g. life events such as death of a spouse, retirement, etc. the imbalance between the perceived demands placed on an individual and his or her perceived capability to deal with the demands. Lazarus & Folkman4 conceptualised stress as an encounter with the environment that is appraised by the individual as taxing his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being. focus on the state or condition of being disturbed. This stress can be: the physiological response to stress can be seen in Table 1, but the clinical manifestations are quite similar to the symptoms of anxiety, which can be grouped under the following headings: - Increased arousal: difficulty falling or staying asleep, irritability, etc.; - Autonomic hyperactivity: palpitations, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, feeling dizzy, etc.; and - Motor tension: trembling, muscle tension, restlessness, etc.

described in terms of unpleasant or negative feelings e.g. anxiety, fear, depression, anger, etc. Behavioural changes can result from these responses. These may include avoiding thoughts about the stressor, absenteeism, abuse of drugs and alcohol, etc. Coping behaviour or reactions to stress Before beginning definitive treatment, we should clearly understand the normal and abnormal reactions to stress. In the past, psychiatrists talked about psychological defence mechanisms such as denial, projection, regression, repression, rationalisation, intellectualisation, projection, displacement, reaction formation, etc. Most of these mechanisms are adaptive during the acute stage, but some can become pathological or self-defeating in the long run. For example, "the sour grapes" rationalisation can be helpful when dealing with an acute loss, but if used all the time can prevent a person from maturing and facing reality. Nowadays, mental health professionals prefer the term "coping" repertoires or behaviours.5 Cohen & Lazarus6 described five general modes of coping behaviour, viz.:

Parker and Brown7 (1982), on the other hand, found 6 types of coping behaviour:

It should be noted that there are some coping behaviours that are more effective than others, depending on the situation and the person involved. Furthermore, a mode useful for a certain individual in a particular situation may do harm or be useless to another person in a different situation or at another time. Stress-related psychiatric disorders Although persons in distress do not always seek help from the medical profession, practicing family physicians do have patients in distressed states and are in a good position to offer help. Rather than immediate referral to a psychiatrist, early recognition of these disorders and prompt treatment are within the scope of a trained frontline doctor. Excessive stress, usually from trauma that is serious or prolonged, can lead to various psychiatric disorders, including depressive disorder,8 somatisation disorder and dissociative disorder. The exact type of disorder that can develop depends on the vulnerability and genetic predis-position of the individual. For example, a person that has a family history of affective disorder is likely to develop a major depressive disorder if under stress. Since stress is closely related to anxiety symptoms, specific anxiety disorders such as panic disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder or generalised anxiety disorder, can result from unbearable stress. Short of the full-blown picture of the above disorders, there are a few specific stress-related mental disorders that need recognition, viz.:

For the first two disorders, the stress involved must be exceptionally acute or catastrophic (involving actual or threatened death or serious injury or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others), thereby causing significant distress to the person or impairment in social or occupational functioning. Stressed patients are also at risk for alcohol or drug dependence abuse.

Besides the general anxiety symptoms of autonomic hyperarousal (hyperactivity of the autonomic nervous system, including palpitations, sweating, hand tremor, etc.) and hyperventilation, there are also some additional symptoms related to the trauma. For a diagnosis of moderate or severe acute stress disorder, one should refer to the ICD-10. It lists the following symptoms:

The DSM-IV, however, added "dissociative symptoms" which include numbness, detachment or absence of emotional responsiveness; reduction in awareness of one's surroundings; derealisation or depersonalisation (feelings that oneself or the environment is not in real existence), and event-related dissociative amnesia (not a genuine loss of memory as in dementia that has a progressive retrograde time element). In addition, there can be some "re-experiencing symptoms" such as recurrent images, thoughts, dreams, illusions, flashback episodes (brief terrifying images of the trauma), sense of reliving the experience; and feelings of distress when exposed to reminders of the traumatic event. The patient often exhibits avoidance behaviour towards stimuli (such as thoughts, feelings, conversations, activities, places, people, etc.) that arouse recollection of the trauma. If the trauma leads to death or serious injury of another person, there can be feelings of guilt about remaining alive or intact, together with self-reproach for not helping the other(s). The patient may neglect personal care and safety, exhibiting impulsivity and risk-taking behaviour. Post-traumatic stress disorder (see below) may develop if the symptoms persist. Social supports, family history, childhood experience, personality variables and pre-existing mental disorders can influence the development of acute stress disorder. The above description may also be modified by cultural factors. For example, dissociative symptoms may be more prominent in cultures in which such behaviours are sanctioned. This disorder has been described in detail elsewhere.9 In some ways, the symptoms are quite similar to those of acute stress disorder, except for the "timing". According to the ICD-10, symptoms should occur within 6 months (with exceptions allowed beyond 6 months) of the stressor or at the end of a period of stress. For the DSM-IV, there are some time specifiers:

The associated features are relatively similar to those of acute stress disorder mentioned above, but the following features are more typical:

It should be noted that not everybody will develop a PTSD or any other psychiatric disorder in response to "stress". Some people remain normal mentally, and a few even grow in character when faced with extreme circumstances. Adjustment disorders occur when clinically significant emotional or behavioural symptoms develop in response to an identifiable stressor (either a single event or multiple items, but not necessarily catastrophic), resulting in functional disabilities. The symptoms may vary in form and severity, but do not include delusions or hallucinations. They must develop after the exposure to the stressor within 1 to 3 months. The DSM-IV subdivides adjustment disorder into acute and chronic by the criterion of 6 months duration. Usually the more acute the onset, the shorter the duration; however the diagnosis does not apply when the symptoms represent bereavement. By definition, the symptoms must resolve within 6 months after the termination of the stressor, unless the stressor is a chronic one or the psychosocial consequences of the stressor are enduring (e.g. financial and relational difficulties). Adjustment disorder should be distinguished from non-pathological reactions to stress when the stressor does not lead to marked distress in excess of what is expected and not cause significant impairment in functioning. Adjustment disorders can be further subclassified into:

Adjustment disorders are quite common, but the prevalence varies widely with the assessment methods used, probably ranging from 20 to 55% in the outpatient setting. Persons with disadvantaged social backgrounds are at higher risk of developing the disorder. Management Generally speaking, good physical health enables a person to withstand stress; in addition, there are a number of mental health promotion measures available,10 such as time management, knowing when to say "no", relaxation exercises, etc. While each disorder may require some specific treatment methods, the underlying principles of the different therapies are similar and are therefore discussed together as below. Psychotherapy Cognitive-behavioural therapy appears to be the most effective method of therapy for stress-related psychiatric disorders. The technique of imagined exposure, for example, is quite effective for post-traumatic stress disorder.11 Cognitive-behaviour therapy techniques can be covert or overt, as outlined below:

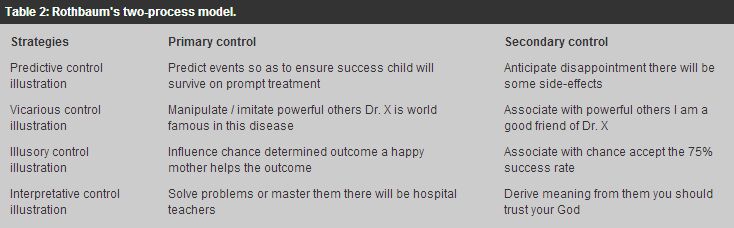

Rothbaum et al12 (1982) describes a two-process model, that of "primary control" (bringing the environment into line with one's wishes) and "secondary control" (bringing oneself into line with environmental forces). There are actually four strategies for both (Table 2 below), and each is illustrated through the case of a mother depressed over her child's recent diagnosis with leukaemia. One can rely on more than one strategy at the same time, and should not be too rigid when applying these strategies.

Pharmaco-therapy Any underlying medical illness, such as thyrotoxicosis, should be appropriately treated. It should be noted that other psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia can present with stress symptoms. In a way, psychopharmacology for stress-related psychiatric disorders is symptomatic and includes mainly the anxiolytics such as the benzodiazepines (e.g. Diazepam) and b-blockers (e.g. Propranolol). Other medications including alcohol or barbiturates have been used with some effect, but drug dependence may become a problem. On rare occasions, anti-psychotics in low dosage can be of use as drug dependence is rare with these medications. In recent years, PTSD has been successfully treated by the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. Sertraline13) or the serotonin modulators (e.g. Nefazodone14), both of which are relatively safe and without the problem of drug dependence. Finally, the use of placebo cannot be ignored, and faith in the medications prescribed by the doctor can be therapeutic. Social treatment "Stress inoculation" has become a fashionable term in stress management. This form of therapy involves exposure to minor stressors with the intent of inducing some coping behaviour that may be useful for future more major stress. There has not, however, been definitive proof of its success. It is not unusual for acute stress to lead to significant psychosocial problems including marital, financial and other social difficulties. Help from various social services can be useful at least in shortening the duration of the symptoms. Grootenhus et al15 describe five adjustment factors that can be developed, including open communication, good social support, good marital relationship, family cohesiveness and satisfactory relationship with the therapist. Assertive therapy is sometimes advocated in order to help the patient cope with further stress. Assertiveness is neither aggression (e.g. scolding others) nor submission (e.g. silence), but an appropriate expression of oneself (e.g. a polite request) in order to achieve the optimal results. Another process is "debriefing", during which the patient goes through the facts, thoughts and feelings of the trauma, followed by advice from the therapist on stress response and management. This has been advocated for PTSD but studies have not confirmed its usefulness.16 For patients who need to adjust to the loss of a loved one, the process of "guided mourning", whereby the patient confronts their memories and says goodbye to the deceased, has been applied with success.17 Interestingly, a fashionable procedure called Eye Movement and Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR) has been found effective for PTSD.18 In this technique, saccadic eye movements are induced by asking the patient to follow rapid side-to-side movements of the therapist's finger. Conclusion Epidemiological studies in the U.S. found that over 60% of men and over 50% of women admitted experiencing at least one recent major stressful event.19 Although vulnerable persons experiencing excessive stress can develop psychiatric disorders, only a relatively small percentage of these subjects had any persisting psychopathology. Nevertheless, stress-related psychiatric symptoms should not be regarded as normal, and should be handled properly. The three different categories of stress-related psychiatric disorders described above are often distinguishable by the time factor alone, and all are amenable to the psychological, pharmacological and social therapies currently available. Such therapies are relatively safe, easy to learn and apply, and can be used independently or in combination. Trained primary care doctors and family physicians are the ideal persons to handle such disorders, as they are in touch with the psychosocial environment of their patients. They can sometimes abort the stresses through proper health education and sound personal advice, and they are better able to call on the patients' relatives for support and care. Prompt referral to psychiatrists should be made when complications occur (such as danger to self or others, treatment failure, co-existence of personality disorder or substance abuse, etc.). Last but not least, all the therapeutic methods discussed above cannot replace a trusting doctor-patient relationship, which by itself is often very therapeutic. Key messages

K Y Mak, MBBS, MD, MHA, FRCPsych

Clinical Associate Professor (Part-time), Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr K Y Mak, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|