|

January 2003, Volume 25, No. 1

|

Discussion Paper

|

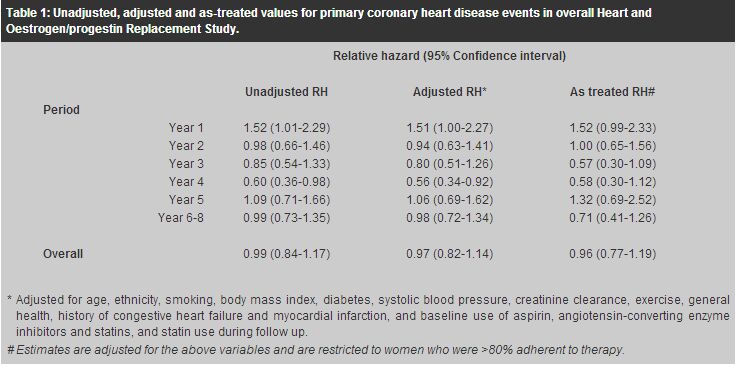

New evidence on risk-benefit profile of combined hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal womenP M Lam 藍寶梅, T K H Chung 鍾國衡, C Haines 韓英士 HK Pract 2003;25:30-36 Summary The risks and benefits of long-term postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) have long been a source of controversy. Based on numerous non-randomised observational studies, most investigators believed until recently that the use of HRT reduces the risk of osteoporosis, colorectal cancer, cardiovascular events, Alzheimer's dementia, and possibly stroke but increases the risk of thromboembolic events and possibly breast cancer. Overall, benefit has been considered to outweigh risk. However, these findings have been criticised as selection bias of relatively healthy women may have affected the observed long-term effects in these non-randomised studies. Recently, two large prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of continuous-combined oestrogen-progestin therapy for postmenopausal women have been published. These studies, the Heart and Oestrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) and the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), have drawn much attention from both the health profession and the public. It is essential for the practitioners prescribing HRT to interpret the study results with care and to convey the message to the public correctly. 摘要 停經後長期服用荷爾蒙補充劑的利弊一直都是個倍受爭議的話題。以往根據大量非隨機性觀察性研究, 醫學界普遍認同荷爾蒙補充劑可減低骨質疏鬆、腸癌、冠心病、老人痴呆症、及甚至中風的風險。 雖然它也增加了患血管栓塞及乳癌的機會,但總而言之利大於弊。但是,這些研究結果一直受到質疑, 因為這些非隨機性研究可能會甄選一些較健康的女士參加,故所觀察到的長期效果亦可能會受到影響。 最近,有兩個關於持續性雌激素加黃體酮混合荷爾蒙補充劑的大型研究結果公佈了。 這兩項前瞻性、隨機、雙盲、安慰劑對照式的研究 [the Heart and, Oestrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS)] & [the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial] 已引起醫學界及公眾的廣泛注意。 醫生在開出荷爾蒙補充劑前,應細心分析了解這些研究結果,並向公眾提供正確的訊息。 Introduction Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been used increasingly by post-menopausal women in Western countries. Women have been prescribed HRT for several reasons: relief of menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, prevention of heart disease and osteoporosis, and for a list of other supposed benefits such as improvement in quality of life. Although treatment of menopausal symptoms is a common indication for the short-term use of HRT, the potential benefits as well as risks of HRT on long-term health outcomes have become an increasingly important consideration. Based on numerous non-randomised observational studies, most investigators believed until recently that the use of HRT reduces the risk of osteoporosis, colorectal cancer, cardiovascular events, Alzheimer's dementia, and possibly stroke but increases the risk of thromboembolic events and possibly breast cancer.1 Overall, benefit has been considered to outweigh risk. However, these findings have been criticised as selection bias of relatively healthy women may have affected the observed long-term effects in these non-randomised studies.2 Two large prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of continuous-combined oestrogen-progestin therapy for postmenopausal women have been recently published. These studies, the Heart and Oestrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS)3-5 and the Women's Health Initiative (WHI),6 are the first two randomised trials on this issue and have drawn much attention from both the health profession and the public. The benefits as well as risks of HRT on long-term health outcomes require reconsideration. Therefore, this article aims to discuss these two studies in detail. It should be emphasised that these two trials examined the use of a particular combination of oestrogen and progestin given on a daily basis. Whilst the results are extremely important, they do not relate to the use of oestrogen alone, nor do they necessarily relate to the use of other oestrogen/progestin combinations. HERS HERS was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled secondary prevention trial of the effect of 0.625mg of conjugated oestrogens plus 2.5mg of medroxypro-gesterone acetate daily on coronary heart disease (CHD) event risk among 2763 postmenopausal women with an intact uterus who had already had established coronary heart disease. Mean age was 67 years (range 55-79). The initial study (HERS I) ended after 4.1 years average follow-up.3 There were no significant differences between the hormone and placebo groups in the CHD events. However, post-hoc analyses suggested a possible higher risk of coronary events during the first year but a subsequent reduced risk after years 3 to 5, so the study was extended in an open-label design (HERS II) by asking participants to consider remaining on their assigned treatment (oestrogen plus progestogen or no active hormones) after consultation with their physicians.4,5 In all, 93% of the original HERS participants (N=2321) were enrolled into HERS II with an additional 2.7 years average follow-up (mean total, 6.8 years). The proportion of women at least 80% adherent to hormone therapy declined from 81% in year 1 to 45% in year 6; while in the placebo group, hormonal use increased from 0% in year 1 to 8% in year 6. With additional years of follow-up in HERS II, it was found that the reduced risk of CHD events in the hormone group after years 3 to 5 in HERS I did not persist. Instead, the risk of CHD events was significantly higher in the hormone group during the first year of HRT (unadjusted relative hazard [RH] 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01-2.29). Overall, with 6.8 years of continuous-combined HRT, there were no significant differences in rates of primary CHD events (non-fatal myocardial infarction and CHD-related death) among women assigned to the hormone group compared with the placebo group (unadjusted RH 0.99; 95% CI 0.84-1.17).4 The results were similar after adjustment for potential confounders, and in analyses restricted to women who were adherent to the assigned treatment. These cardiovascular disease outcomes of HERS are summarised in Table 1.

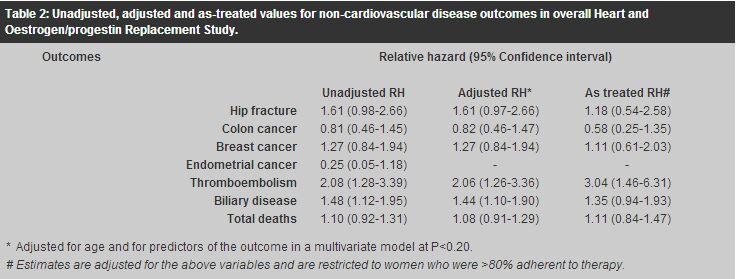

Apart from the lack of efficacy for secondary prevention of CHD, treatment with continuous-combined HRT did not show favourable trends in other non-cardiovascular disease outcomes among these women.5 There were significantly higher rates of venous thromboembolism (unadjusted RH 2.08; 95% CI 1.28-3.39) and biliary disease (unadjusted RH 1.48; 95% CI 1.12-1.95) among women assigned to the hormone group compared with the placebo group. When the risk for venous thromboembolism was examined by year of observation, the RH declined after the first 2 years, but the time trend was not statistically significant (P=0.08). Moreover, there were no significant differences in the rates of fractures, colon cancer, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and total deaths. Adjusted and as-treated analyses did not alter the conclusions. These non-cardiovascular disease outcomes are summarised in Table 2.

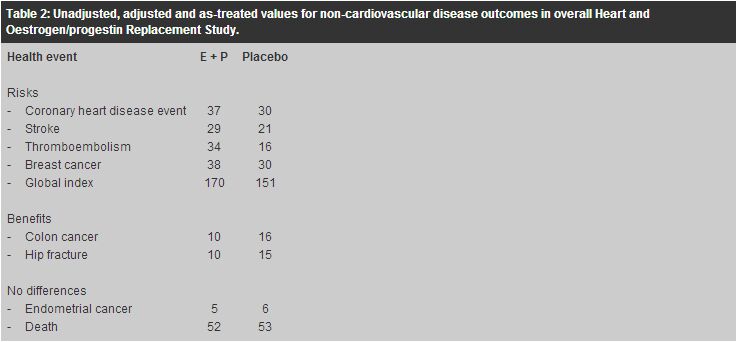

The conclusions drawn by the HERS investigators were that postmenopausal HRT did not reduce risk of CHD events in women with established CHD and trends in other disease outcomes were also not favourable. Therefore, in the viewpoint of HERS investigators, postmenopausal HRT should not be used for secondary prevention of CHD events. WHI study WHI was a multi-centre observational study in predominantly healthy postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years (mean age 63).6 In contrast to the secondary prevention trial of HERS, WHI was a primary prevention trial aiming to assess the major health benefits and risks of HRT in healthy postmenopausal women. It consisted of a set of three interrelated clinical trials: the randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled hormone part of continuous-combined HRT arm for women with a uterus (N=16,608) and oestrogen-only arm for women without a uterus (N=10,739), as well as the ancillary part evaluating memory, dementia, low-fat diet, calcium and vitamin D. The continuous-combined HRT arm used the same drug combination as the HERS study, and the trial was terminated prematurely in July 2002 after an average of 5.2 years follow-up because the overall risks were thought to exceed the benefits. At study end, adherence rates were only 58% for the hormone group and 62% for the placebo group. The oestrogen-only arm continues, as does the ancillary part. Although the study population of WHI was younger and generally healthier than that of HERS, it differs from our local Chinese population considering or using HRT. More than 80% of them were white Caucasian and only about 2% were Asian. Among the 8,506 women randomised to continuous-combined HRT, 33.4% were 50 to 59 years old, 45.3% were 60 to 69 years old, and 21.3% were 70 to 79 years old. With the mean age of menopause being 50 years old, two-third of them aged 60 years had been menopausal for more than 10 years. Also, about a quarter of them had been using hormones before the trial entry, and among them, 30% had used it for more than 5 years. The study population was in general overweight with an average body mass index of 28.5kg/m2, and half of them were either current or past smokers. At trial entry, 7.7% had established cardiovascular disease. In addition, 35.7% of the treatment group and 36.4% of the placebo group had been treated for hypertension whilst 12.5% of the treatment group and 12.9% of the placebo group had been treated for hypercholesterolaemia. These potential differences in patient characteristics from our local population limit the generalisability of the trial results. Concerning the long-term health risks of continuous-combined HRT, compared with the placebo group, the hormone group had a higher CHD event rate (37 versus 30 per 10,000 person-years), a higher stroke rate (29 versus 21 per 10,000 person-years), a higher rate of venous thromboembolism (34 versus 16 per 10,000 person-years), and a higher rate of breast cancer (38 versus 16 per 10,000 person-years). There were no differences between groups in endometrial cancer rates (5 versus 6 per 10,000 person-years) or all-cause mortality (52 versus 53 per 10,000 person-years). Beneficial effects of HRT included a lower rate of hip fractures (10 versus 15 per 10,000 person-years) and lower rate of colorectal cancer (10 versus 16 per 10,000 person-years). However, as a whole, the summary global index showed a net harm, with 15% higher adverse outcome rate in the hormone group (170 versus 151 per 10,000 person-years). These results are summarised in Table 3. The increased risk of venous thromboembolism and breast cancer as well as the reduced risk of hip fractures and colorectal cancer were compatible with the previous non-randomised observational studies.1,7 More importantly, the observed higher rate of CHD events and stroke in the hormone group supported the HERS findings that have contradicted the previous non-randomised studies.

Time-to-event analysis was used to examine the long-term health risks of continuous-combined HRT by assessing the cumulative hazards of the related clinical outcomes along time. A diverging time-to-event curve indicates increasing difference between the treatment group and the placebo group. The time-to-event analysis showed that the curves for breast cancer remained similar for about 4 years before diverging. Also, the subgroup analyses revealed that the breast cancer risk was significantly higher in the HRT group only among the women who had used hormones before the trial entry (RH 2.21; 95% CI 1.35-3.62) but not among those who had never used hormones before (RH 1.06; 95% CI 0.81-1.38). This was compatible with the findings of previous non-randomised studies in that tTime-to-event analysis was used to examine the long-term health risks of continuous-combined HRT by assessing the cumulative hazards of the related clinical outcomes along time. A diverging time-to-event curve indicates increasing difference between the treatment group and the placebo group. The time-to-event analysis showed that the curves for breast cancer remained similar for about 4 years before

he increased breast cancer risk associated with HRT was mainly concentrated in long-term

users with Discussion At first glance, the HERS and WHI results appear very convincing because they were both well-controlled trials with large sample sizes. While much attention has been drawn to these trials, the results should be interpreted with care by the health profession and the message conveyed to the public should not be biased or misleading. Firstly, the patient characteristics of the study population of both trials were very different from our local population. The HERS population all had documented CHD, and they averaged 67 years old on trial entry and 74 years old at the end of HERS II. The absolute risk of CHD events will certainly be higher in this older population with established CHD, as compared with those we would usually see around the time of the menopause for consideration of treatment. Similarly, the absolute risks of the outcomes (CHD, stroke, thromboembolism, and breast cancer) on which continuous-combined HRT may have a harmful effect would be higher among the WHI study population because it has more prevalent risk factors such as being Caucasian, old age, smoker and being overweight. In this way, the harmful effects of HRT may be exaggerated in these high-risk groups. On the other hand, even with HRT, it may be too late for women who have been menopausal for more than 10 years to reverse the harmful effect of prolonged hypoestrogenism on bone. Therefore, the generalisability of HERS and WHI study results to our local population is in doubt. Secondly, neither HERS nor WHI trials targeted highly symptomatic postmenopausal women despite treatment of menopausal symptoms being a common reason for seeking medical advice or the commencement of HRT. Although HERS reported no effect of continuous-combined HRT on quality of life (QOL) after menopause, this finding was criticised for not targeting the most relevant population (symptomatic menopausal women) and not using a validated QOL instrument. Also, the current WHI report has not addressed a variety of other conditions for which continuous-combined HRT may or may not provide a favourable effect, including menopausal symptoms, quality of life, and cognitive function. Therefore, the reported risk-benefit profile of continuous-combined HRT may not be complete. Hopefully, the on-going ancillary parts of WHI trial, WHI Memory Study (WHIMS) and WHI Study of Cognitive Aging (WHISCA), may help determine whether HRT has an effect on cognitive function. Thirdly, only one particular oral form of continuous-combined HRT, 0.625mg of conjugated oestrogens plus 2.5mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate daily, has been evaluated in the HERS and WHI trial. It is not possible to generalise the data to other oestrogens and progestin regimens, oestrogen-only regimens, other dosages, and other routes of administration. However, a better risk-benefit profile of other HRT regimens cannot be assumed until proven. Despite the above limitations, these trials did give us some new insight about the use of postmenopausal HRT. Continuous-combined HRT should not be used primarily for either primary or secondary prevention of CHD events. Proven alternative cardioprotective regimens should be considered instead. The effect of oestrogen-only therapy on CHD remains unclear. Until confirming data are available, oestrogen-only therapy should also not be used for primary and secondary prevention of CHD. Many HRT products are FDA-approved for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis; however, because of the potential risks associated with HRT, alternative treatments for osteoporosis should also be considered. Most importantly, an individual risk-benefit profile is essential for every woman contemplating any HRT regimen and she should be informed of the potential risks. With proper counselling, an informed decision about the use of postmenopausal HRT can be made and reviewed annually with both the clinician and the patient. Conclusion While HRT remains an effective treatment for moderate or severe postmenopausal symptoms, extended use of HRT as primary prevention of chronic disease should be considered and counselled on the basis of individual risk-benefit profile. Key messages

P M Lam, MRCOG

Medical Officer, T K H Chung, MD Professor, C Haines, MD Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr P M Lam, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong.

References

|

|