|

January 2003, Volume 25, No. 1

|

Update Articles

|

Dietary management of type 2 diabetes mellitusT Y T Chan 陳艷婷 HK Pract 2003;25:22-28 Summary Dietary guidelines for medical nutrition therapy (MNT) of people with diabetes mellitus have undergone considerable revision and the most updated one was published in 2002 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).1 Knowledge and application of dietary guidelines for MNT of patients is of prime concern. The aim of this article is to review the dietary management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Hong Kong based on current guidelines. 摘要 隨著科學發展,糖尿病飲食治療的指引也作出了不少修正。2002年, 美國糖尿病協會刊登了最新的糖尿病飲食指引。明瞭和應用糖尿病飲食治療對病人至關重要。 這篇文章的目的是根據最新的指引,回顧香港二型糖尿病飲食治療的概況。 Introduction The incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasing at an alarming rate and at a younger age. In Hong Kong, the prevalence of type 2 DM is around 10% and accounts for over 90% of all cases of DM.6 Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) for people with DM remains a mainstay of diabetic control. No matter what medical treatments they are receiving, the ingestion and utilisation of nutrients from food they choose to eat affect metabolic control. Effective management of people with type 2 DM cannot be achieved without proper attention to diet and nutrition.5 Dietary management Dietary management of DM should be geared towards individual biochemical and lifestyle parameters in order to help patients to make changes in dietary and exercise habits that lead to improved overall metabolic control. It can be considered in terms of five key goals:1

- to optimise blood glucose levels

Figure 1: The food guide pyramid.

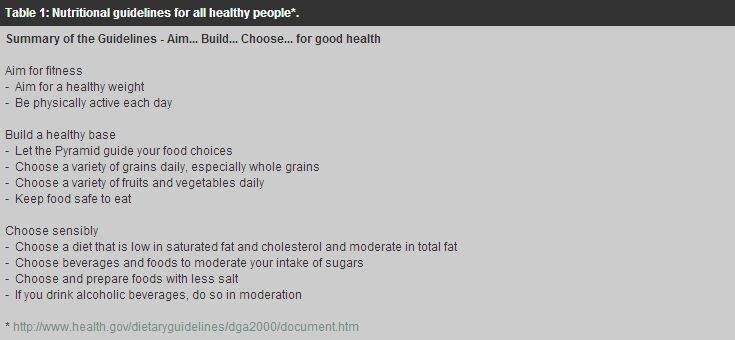

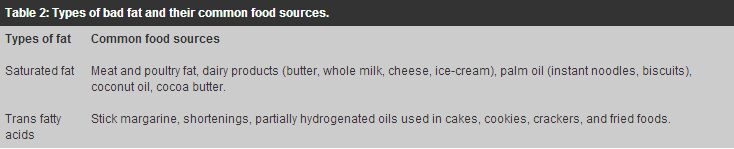

Obesity The majority of people with type 2 DM are overweight or obese. Excess body fat leads to insulin resistance, resulting in high blood glucose and may also aggravate hyperlipidaemia and hypertension. Weight reduction should be targeted as primary dietary intervention in obese type 2 DM. Many studies show that a modest weight loss (5-10% of body weight) can cause dramatic improvements in blood glucose levels, lipid profile, blood pressure management and also life expectancy.7 Very-low-calorie diets (VLCD), 800kcal or fewer calories daily have reported to be effective for weight loss and resulted in rapid improvements in blood glucose and lipid levels in people with DM.8,9 It is considered to be safe when prescribed under medical supervision, as a short-term application for obese people. However, most people treated with VLCDs cannot maintain the body weight in the long term. Modest calorie restriction with accompanying behaviour therapy to achieve/maintain desired body weight should be most appropriate.10 Decrease in energy intake can be achieved by healthy food choices, cutting down on fat and sugar, reducing habitual portion sizes and eating regular meals based on Food Guide Pyramid. Realistic energy deficits of 500kcal per day usually produce better end results than very restrictive diets, leading to a weight loss of approximately 0.5 - 1kg per week. Patients may benefit from supportive strategies such as individual counselling or group therapy. Intensive lifestyle intervention that included a low-fat diet, increased physical activity, educational sessions and frequent follow-up were shown to be effective for losing body weight and sustaining weight loss.1 Exercise is encouraged as a most useful adjunct to dietary management and is important in the long-term maintenance of weight loss. Exercise improves insulin sensitivity, which actually lowers blood glucose and may also lower blood lipid, blood pressure and stress. Regular physical activity such as brisk walking or cycling for at least 30 minutes at moderate intensity is recommended daily.5 Energy prescription Body weight and activity levels dictate calorie requirement. Nutrition guidelines have progressed from very restrictive to fewer diet restrictions. Recommended nutrient energy distribution for people with DM is 15 to 20% of calories from protein and the remaining calories from carbohydrate and fat.1 Carbohydrate and monounsaturated fat should together provide 60-70% of energy intakes.1 Such dietary flexibility brings responsibility. The medical team needs to provide diabetic patient with self-management skills while the dietitian tailors meal plans to energy requirement of the individuals. Protein Protein intakes should comprise approximately 15 to 20% of total daily energy intakes. There is no need for modification if renal function is normal. High protein, low carbohydrates diets have claimed to produce short term weight loss and improved glycemia.1 However, there is no evidence of long-term success in addition to extra renal load. Most of these diets also tend to be high in fat and may increase plasma LDL cholesterol. Therefore, people with type 2 DM should maintain their meat group (meat, poultry, fish, seafood and meat alternatives) intake in moderation. Fat People with DM have a 3- to 4- fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease as accelerated artherogenesis is associated with DM.13 Generally, they should follow the same fat recommendation for the general public: i.e. less than 30% of calories from total fat, less than 10% from saturated fat and less than 300mg of cholesterol per day. Intake of saturated fat and trans-fatty acids should be curtailed, as they are associated with increased LDL cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein, the 'bad' cholesterol). People with high LDL cholesterol may benefit from lowering saturated fat intakes to less than 7% of daily calorie intake. Thus, they should be discouraged from taking foods high in saturated fat and trans-fatty acids, such as foods with high animal fat (lard, butter, chicken skin, luncheon meat), palm oil (found in instant noodles and biscuits), coconut oil and hard margarine. (Table 2)

Patients with elevated triglycerides and high LDL cholesterol may benefit from getting more monounsaturated fats in their diets. Studies show that monounsaturated fats result in desired decrease in total and LDL cholesterol without the deleterious effects of hyperglycaemia, hyerinsulinemia, hypertriglyceridemia and reduced HDL cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein, the 'good' cholesterol) concentrations associated with high carbohydrate and low fat diet.14 Monounsaturated fats are commonly found in foods like olive oil, canola oil, avocado, peanut butter and nuts. However, increasing fat intake may result in increased energy intake as all kind of fat gets the same high energy density (9kcal/g compared to only 4kcal/g for carbohydrate or protein). (Figure 2)

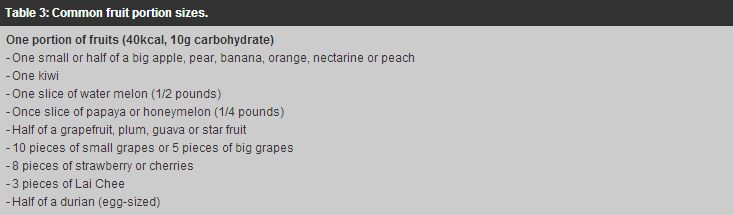

Figure 2: Breakdown of fat types in various oils. Alcohol Ingestion of moderate amounts of alcohol with food has no acute effect on blood glucose or insulin levels of people with DM.1 As alcohol suppresses gluconeogenesis and has a hypoglycaemic effect, alcohol should not be taken on an empty stomach. Daily alcohol intakes should be limited to one drink per adult women and two drinks per adult men. One drink is defined as a 12-ounce beer, 5-ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounce distilled liquor.4 Excessive chronic ingestion of alcohol increases blood pressure and hypertriglyceridemia, and thus may increase the chance of stroke. Alcohol provides no nutritional value and is a concentrated source of energy (7kcal/g). Obese type 2 DM should be discouraged from taking it. Carbohydrate The importance of including food containing carbohydrate from whole grain foods, fruits, vegetables, and low-fat milk in the diet is promoted for healthy people as well as people with DM. ADA gives the consensus that carbohydrate and monounsaturated fat should together provide 60-70% of energy intake. The British Dietetic Association suggests that intakes of 45-60% energy from carbohydrate are compatible with good diabetic control and a diet containing about 50% carbohydrate energy is a realistic objective in the UK.3 Regular meals based on starchy foods with plenty of vegetables may help reduce the amount of energy dense foods (e.g. meat, fish, seafood) consumed. Regarding the glycaemic effect of carbohydrates, there is strong evidence that the total amount of carbohydrate in meals or snacks is more important than the source or type.1 The belief that a diet free of sugar, or sucrose, is the most important dietary modification in the MNT for DM is commonly held but incorrect. Sugar is no longer prohibited for people with DM. Numerous studies indicate that blood glucose profiles are similar when sucrose is substituted for part of the total carbohydrate intakes of the diet. Current guideline is that sugar intakes should not exceed 10% of the daily dietary energy.4 A small amount of sugar used in cooking is fine. However, high sugar food, like cakes, pineapple bun, ice cream and desserts, should only be taken in small portions and infrequently, as they tend to be high in fat and calories. Carbohydrate content of these foods must also be counted as part of the carbohydrate loading of the diet. Sweeteners Nutritive sweeteners (e.g. fructose and sugar alcohols (polyols)) are not recommended due to their energy content, cost or laxative effect. Non-nutritive sweeteners (e.g. saccharin, aspartame, acesulfame K) are safe for use when consumed within the established Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) levels. Current actual intake is much less than the ADI. The daily ADI for aspartame is 50mg/kg body weight but the range of actual daily aspartame intake at the 90th percentile is 2-3mg/kg body weight.1 People with DM may use them as sugar substitute in foods. Fiber Dietary fiber promotes satiety and gastrointestinal motility. Daily intakes of 20 to 35g of fiber are generally recommended. Increased intakes of fiber (~50g per day), especially soluble fiber, may reduce total and LDL cholesterol and cause a decrease in postprandial blood glucose levels.15 However, there is concern of the palatability and gastrointestinal side effects (e.g. flatulence, stomach upset) of such high levels of fiber intake. Food sources of soluble fiber are oatmeal, legumes, fruits and vegetables. People with DM are generally recommended to have at least 6tael/ounces of vegetables and 2 portions of fruits per day (Table 3). High fiber foods tend to be high in vitamins and minerals.

Vitamins and minerals Patients with diabetes mellitus may be in a state of increased oxidative stress. Antioxidant vitamins like Vitamins C and E are believed to help alleviate the damaging effects of high blood glucose on cells and thus minimise the risks of complications.17 There is no clear evidence of benefit from vitamin or mineral supplementation in people with DM who do not have underlying deficiencies.1 There is also concern about potential long-term toxicity of mega dose antioxidants. The best and safest way to get adequate vitamins and minerals is a well-balanced diet through a good variety of food choices, especially fruits and vegetables. Diet counselling Effective dietary management of DM requires the consideration of many factors like body weight, calorie requirement, status of biochemical parameters and lifestyle. It is prudent that the service of a registered dietitian be made available to people with DM, so that individualised meal plan and appropriate nutrition therapy can be implemented. There is evidence for intensive nutritional intervention providing significant improvement in glucose control.2 The benefits of keeping tight glucose control was also shown in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and UK Prospective Diabetes Study.17,18 The dietitian is recognised as an important team member in educating patients on nutrition, improving adherence in order to achieve HbAlc goals and prevent or delay diabetes-related complications. Conclusion Medical nutrition therapy should be considered, along with physical activity in the initial treatment of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. When oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin are needed, additional encouragement of diet adherence and physical activity, improvements in diabetes self-management knowledge and skills are also crucial. To achieve tight control of blood sugar, people with diabetes mellitus should ideally see a registered dietitian for an individualised diet. They should get physically active and have self-management knowledge and skills for diabetes mellitus. Key messages

T Y T Chan, BSc(Hons), PgDip(Dietetics), SRD(UK)

Dietitian, Dietetic Department, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to : Ms T Y T Chan, D ietetic Department, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

|