|

March 2003, Volume 25, No. 3

|

Original Articles

|

Evaluation of systolic murmur in the elderlyK S Ho 何健生, T K W Tam 譚嘉渭 HK Pract 2003;25:114-121 Summary

Objective: To study the underlying pathology of systolic murmur

in the elderly.

Keywords: systolic murmurs, elderly, echocardiographic examination 摘要

目的: 探討老年人心臟收縮期雜音病理成因。

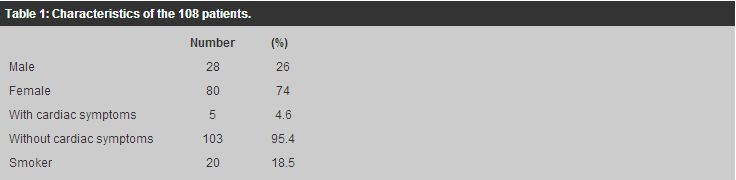

Introduction Heart murmur is a common abnormal auscultatory finding on cardiac examination. It occurs in 80-96% of children and 15-44% of adults.1 Some data also suggests that innocent systolic aortic murmur is present in 30% of the elderly.2 The two main causes of heart murmurs, functional and organic, have different diagnostic and prognostic implications. Functional or innocent murmurs are always systolic in timing; they are usually soft and often vary with the patient's posture; they are heard only over a small area and do not radiate widely; they do not cause cardiac enlargement and the patient is free of exertional symptoms.3 They are related to aortic flow, increased intraventricular velocities, and vibratory phenomena. For the elderly, causes also include dilated aortic annulus, tortuosity of vessels, or atherosclerotic changes over the aortic valve. Murmurs also occur in a hyperdynamic circulation when an abnormally large amount of blood crosses a normal valve, as in anaemia, thyrotoxicosis, CO2 retention and beri-beri.4 In actual practice, it is often a clinical challenge to determine the pathological basis of an individual heart murmur on cardiac auscultation especially in the aged population. In an aging heart, there may be a lot of degenerative processes and age-related structural changes. Valve thickening, fibrosis and calcification, atherosclerosis, reduced valve mobility and subsequent stenosis are recognised age-related findings.2 Studies in other countries have shown that aortic sclerosis, aortic stenosis and mitral annular calcification are common causes of heart murmurs in the elderly. Prevalence rates of 29%, 2-7% and 8% respectively have been reported.6-9 There has also been a surge of interest to prove the positive correlation of these conditions with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular adversity.6,8-12 In our practice, we also encounter systolic murmurs in many of the community-dwelling elderly. There has been no previous report on the findings of these murmurs in the local population. Therefore, in our study, we have looked into this subject by evaluating the murmurs echocardiographically, delineating the underlying pathology and identifying any possible associations with cardiovascular risk factors for a subset of systolic murmur. Methodology Study population Within the study period of year 2000, we examined 2,435 subjects, 775 male and 1,660 female, aged 65 and above who voluntarily attended Health Centre for the elderly. One hundred and eight were found to have systolic heart murmur of grade 2/6 on physical examination by a single doctor. All of them were referred to a cardiologist for echocardio-graphic assessment. Relevant demographic data, smoking status, associated cardiac symptoms, medical co-morbidities including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease, previous myocardial infarction, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, thyrotoxicosis and anaemia and electrocardio-graphic findings were recorded and analysed. Echocardiography All referred subjects agreed to undergo transthoracic two-dimentional and Doppler echocardiography in the supine and left lateral decubitus positions by the same cardiologist. The aTL Apogee 800 Plus echocardiographic machine with a 2-4MHz transducer aTL convex phased array 4-2 C15 was used. The images were recorded on videotapes via a Sony SVHS video recorder and photographed on Polaroid films using a Sony video graphic printer VP890 MD. Echocardiographic measurements were performed according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography. Abnormal valves were those with abnormal leaflet thickness or mobility or a valve mass. Regurgitation was documented by colour Doppler. Normal leaflet thickness was taken as 0.7mm to 3mm. Any leaflet with thickness >3mm was considered abnormal.5 Aortic sclerosis was defined by focal areas of increased echogencity and thickening of the aortic-valve leaflets without restriction of leaflet motion or valvular gradient on Doppler.6 Aortic stenosis was diagnosed when, in addition to calcification of the aortic valve, there was restriction of cusp mobility and reduced systolic opening.2,6 The Doppler-determined estimate of systolic pressure gradient across the aortic valve was calculated by the modified Bernoulli equation P=4V2 where P is the peak pressure gradient in mm Hg and V is the maximal velocity squared in m/sec.17 Echocardiographic signs of flail mitral leaflet included systolic echoes within the left atrium, coarse diastolic fluttering of the mitral leaflets, paradoxic posterior mitral leaflet motion and systolic flutter of the mitral closure line.18 For mitral valve prolapse, the M mode criteria consisted of mid- to late systolic posterior motion (2mm) of at least 1 mitral leaflet and holosystolic hammocking (3mm) of any mitral valve leaflet. Other M mode features were shaggy diastolic echoes, heavy cascading echoes, reduplication of systolic echoes and abutment of the mitral valve E point against the septum.19 Statistic analysis The association of atherosclerotic risk factors with aortic sclerosis was analysed using Pearson Chi-square test, Fisher Exact test, logistic regression model and two sample t-test. Results The characteristics of the 108 studied subjects are listed in Table 1. The mean age of our study population was 75.4 years (range 66 to 91 years); 74% of them were female. Twenty (18.5%) of them had ever smoked (seven current smokers and thirteen ex-smokers). Five (4.6%) of them were symptomatic, one patient with heart failure (Class II, New York Heart Association Classification) and four with stable angina. (Class II, Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification)

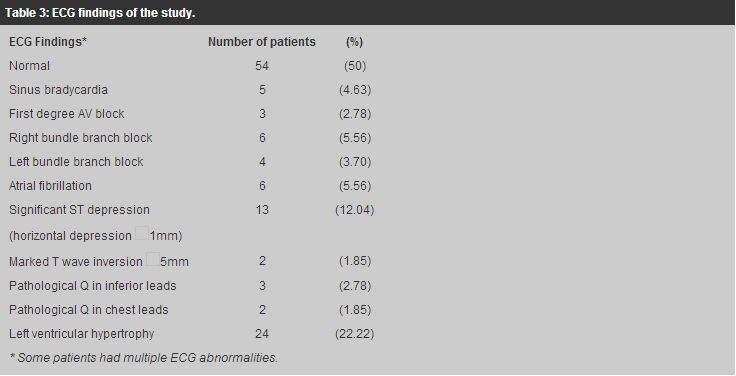

The medical co-morbid states depicted in Table 2 included hypertension (71.3%), diabetes mellitus (13.89%), angina pectoris (10.19%), history of myocardial infarction (0.93%), thyrotoxicosis (2.78%) and anaemia (2.78%). Some had more than one co-morbid state. The ECG findings were summarised in Table 3.

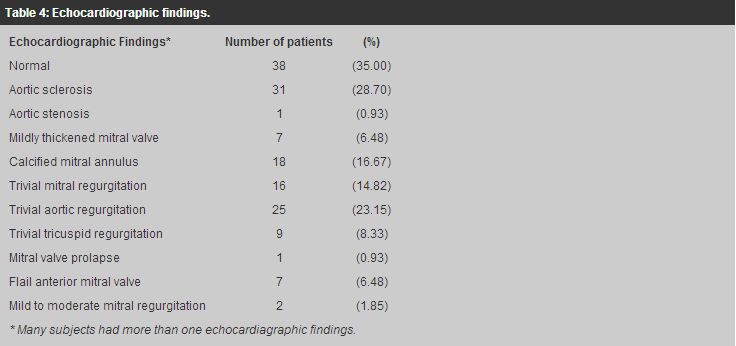

In this study, the posterior wall of the left ventricle of 3 patients could not be properly assessed because of technical difficulties. Among the 108 subjects (Table 4) with systolic heart murmur, the majority of the echocardiographic findings were age-related changes only, which commonly involved the aortic and mitral valves. The age-related features included valve thickening and calcification as in aortic sclerosis (28.70%), mildly thickened mitral valve (6.48%) as well as calcified mitral annulus (16.67%). One patient (0.93%) had aortic stenosis as a result of severe aortic valve sclerosis but the peak gradient across the aortic valve was less than 30mmHg.

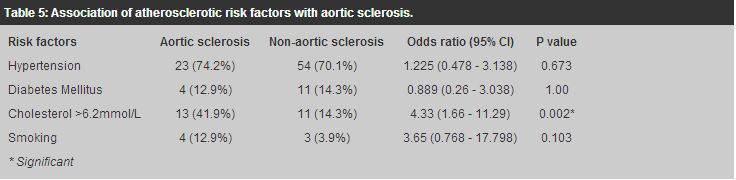

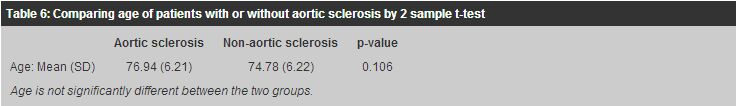

Normal echocardiographic findings were found in 38 patients (35%). Mitral valve prolapse without regurgitation occurred in 1 person (0.93%) only and 7 patients (6.48%) had mildly flail anterior mitral valve. Trivial regurgitation detected by Doppler through the mitral valve (14.82%), aortic valve (23.15%) and tricuspid valve (8.33%), were frequent. These could be related to the degenerative process. There were 2 patients (1.85%) with mild to moderate mitral regurgitation of whom one suffered from dilated cardiomyopathy. Most of the subjects had more than one echocardiographic abnormality. Combined aortic and mitral valve disease were a frequent combination. Calcified mitral annulus was commonly associated with aortic sclerosis. The association of aortic sclerosis with the athero-sclerotic factors - age, hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolaemia - was analysed using Chi square test and two sample-t test. There was evidence that cholesterol >6.2mmol/L was more commonly associated with aortic sclerosis; odds ratio = 4.33 (95% CI=1.66-11.29), p value=0.002 (by Pearson Chi-square test), whereas other risk factors did not show any significant association. (Tables 5,6) Logistic regression model analysis after adjusting for age and sex also revealed that subjects with cholesterol >6.2mmol/L were 4 times more likely to have aortic sclerosis; odds ratio being 4.00 (95% CI=1.37-11.61).

Discussion Systolic murmurs, so frequently found in older patients, often present a puzzle to primary care physicians. In Hong Kong, there has been no related study on the Chinese elderly. This study could give valuable information on the common lesions in these elderly people. Referring to our results, most of the lesions were clinically insignificant, of which 35% of the study population had normal echocardiographic findings (functional murmurs). The rest were mainly lesions related to degenerative process. Aortic sclerosis was common. The prevalence among our subjects (28.7%) was comparable with overseas studies (29%).9 In contrast to their results, we did not demonstrate any significant association with cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. This could be due to the fact that our sample was small and was Chinese. Further studies would be needed to lead us to a different conclusion. Second to aortic sclerosis, mitral annular calcification occurred in 16.67% of our subjects. Some reports have proposed that both mitral annular and aortic valve calcification should be regarded as comparable expressions of underlying age-related cardiac manifestations of atherosclerosis.8 There has also been increasing interest to determine the correlation of submitral calcium with cardiac morbidity and thromboembolic cerebrovascular events.10-13 These associations may be explored in further local studies. On Doppler studies, trivial mitral, tricuspid and aortic regurgitation of no clinical significance may be detected in any age group, but are particularly common in the elderly and our findings were comparable to other studies.2 The prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in our subject population was low (0.93%) when compared with the Caucasian (5-10%).2 None of our subjects were found to have significant aortic stenosis, while prevalence of 2-7% has been reported in Western countries.9 The fact that our population was recruited from the community "well" elderly may partly explain the discrepancy. Aortic stenosis forms the late stage in the development of aortic valve abnormalities where the valve leaflets have become increasingly sclerosed and finally stiff enough to result in obstruction of ventricular outflow. The numbers with aortic stenosis in this study are very small (0.93%) compared with overseas figures. The only patient with aortic stenosis had a transvalvular gradient of <30mm Hg which is considered to be mild.1 The natural history of aortic stenosis consists of a long latent period during which sudden death is uncommon. Mild aortic stenosis may take 15 or more years to progress to severe.14 Mortality rises sharply soon after the onset of symptoms to 3% in the first few months and around 50% at 3 years.15 In clinical practice, differentiation between aortic stenosis and aortic sclerosis is important. Cardiac symptoms are absent in aortic sclerosis. The classical physical findings of the two conditions differ. The carotid pulse and apical impulse are normal in aortic sclerosis. Reverse splitting of the second heart sound is absent. The murmur is soft, occurring in the early to mid-systole; and being best heard at the apex with radiation from base to apex. On the contrary, patients with aortic stenosis have a small carotid pulse with slow and prolonged upstroke, and a sustained, laterally displaced apical impulse. Second sound paradoxical splitting is more frequent, and the murmur is of greater intensity; heard in the mid-to late systole with late peaking; over the second right intercostal space with radiation to both carotids.16 It is important to be aware of the possibility of aortic stenosis in the elderly. Echocardiography should be requested in patients with a loud murmur in the aortic area, with any suggestion of exertional symptoms or clinical signs of heart failure. Ausculatation, although poor at differentiating moderate from severe aortic stenosis, is more reliable at confirming mild stenosis in those without symptoms. Asymptomatic patients with soft, short ejection systolic murmurs and well-heard second sounds are unlikely to have severe aortic stenosis, and do not require echocardiography.15 Some studies have shown the association of aortic valve sclerosis and atherosclerotic factors such as smoking but this is not evident in our study.6 It could be due to the fact that our sample is relatively small; the sample size would need to increase to 324 to achieve 80% power to detect a smoking-related difference between groups with, or without, aortic sclerosis. Our study population is Chinese which could be another relevant factor but this ethnic effect requires further confirmation. In fact, the greatest limitation of this study is that our population is a biased sample and does not represent the elderly population as a whole. Conclusion Most of the systolic heart murmurs in the elderly in our study were clinically insignificant, either being functional or just a reflection of aging changes of which aortic sclerosis and calcified mitral annulus were the commonest. Aortic stenosis was not common in this study. However, it is essential to identify these elders because this diagnosis carries a different clinical implication. Asymptomatic patients with soft, short ejection systolic murmurs and well-heard second sounds are unlikely to have severe aortic stenosis, and may not require echocardiography. Echocardiography should be recommended for all patients with systolic murmurs who have cardiac symptoms, such as heart failure, dysnoea or chest pain.1 There is an association of hypercholestrolaemia with aortic valve sclerosis whereas the relationship with other atherosclerotic factors in Chinese elderly needs further study. Acknowledgement I am indebted to Ms Shirely L Y Chan , research officer of Elderly Health Service, Department of Health, who has helped in compiling the statistics and given expert advice. n Key messages

K S Ho, FHKAM(Medicine), FHKAM(Family Medicine)

Consultant (Family Medicine), T K W Tam, MBChB Medical Officer, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Dr K S Ho, Consultant (Family Medicine), Elderly Health Services, Department of Health, 35/F, Hopewell Centre, Wanchai, Hong Kong.

References

|

|