|

March 2003, Volume 25, No. 3

|

Update Articles

|

|||||||

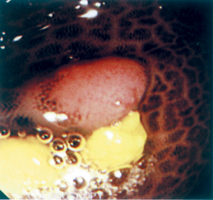

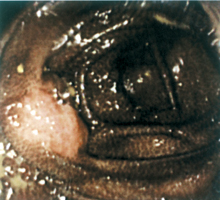

Melanosis coliA C W Mui 梅中和 HK Pract 2003;25:124-126 Summary Melanosis coli is an endoscopy feature of blackening of the colonic mucosa. Although by itself a benign condition, it may underlie prolonged laxative abuse, with its deleterious sequel on the digestive system. Family physicians should be aware of this condition, and be prepared to identify laxative abusers and to educate them on the proper use of laxatives. 摘要 結腸黑變病以內窺鏡下結腸黏膜變黑的特徵。雖然是良性的病變,但可能源於長期濫用輕瀉藥,對消化系統產生不良的後遺症。家庭醫生應有所了解,識別濫用輕瀉藥的病例,並適時教育病人有關輕瀉藥的正確用法。 Introduction Increased pigmentation in the body tissue is a common phenomenon of normal aging. The most discernible pigmentation is senile lentigo on the skin due to deposition of melanin. Lipofuscin is another pigment which increases in the myocardium, skeletal muscle, liver etc with increasing age.1 Lipofuscin is biochemically distinct from melanin and shows a characteristic autofluorescence.2 Non-aged related deposition of lipofuscin occurs in the melanosis coli (so-called "brown bowel syndrome") as described below, as well as in many other organs, such as the thyroid, oesophagus, and the gall bladder.1 This condition, whereby the normal pinkish colonic mucosa became diffusely infiltrated by dark pigmentation, was described as early as 1825. The term, melanosis coli, was coined by Virchow in 1857. Pathogenesis Melanosis coli was found to be related to chronic ingestion of anthraquinone laxatives as early as the 1920s. In experimental animals (guinea pigs), per oral administration of anthraquinone compounds resulted in a dose-related apoptosis of colonic surface epithelial cells. These degraded products were phagocytosed by macrophages in the epithelium and transported to the lamina propria. Here the apoptotic bodies were transformed into lipofuscin and stored in the macrophage. The same pathology was found in colonic biopsies of patients with melanosis coli.3 The pigment was originally thought to be melanin, hence derivation of the name melanosis coli. Electron microcopic techniques have now elucidated that the pigment deposited in the colon is in fact lipofuscin.4 Pseudomelanosis coli is a more accurate description of the condition as the pigment is lipofuscin rather than melanin. However the original term, melanosis coli, gains much wider acceptance. The affected cells look normal under light microscopy but showed pathological changes including loss of microvilli under electron microscopy.5 In guinea pigs, macrophages are most abundant in the caecum, decreasing towards the rectum. This explains the abundance of melanosis in proximal as opposed to the distal colon. Interestingly in humans, the same distribution pattern occurs, the most frequent sites of involvement being the caecum and the appendix.6 With a sufficient dose and duration of laxative ingestion, the entire colon may be involved. It is now known that chronic ingestion of anthraquinone compounds is the single most important cause of melanosis coli. Anthraquinone compounds are present in many of the over-the-counter laxatives, including herbal medicine. These include rhubarb root, cascara, senna leaf (as well as sennosides) and aloe. Laxatives are used by the lay population not only to treat constipation, but also to get rid of "harmful toxins" from the gut and thus the body. Such purgation is thought to promote health and enhance one's natural beauty. In addition, laxatives are frequently used as slimming agents, usually in the form of herbal teas, as a result of media propaganda that "slim is beautiful". Anyone who scans the local press will be overwhelmed by advertisements of slimming agents and agencies. Apart from laxative abuse, melanosis coli has been reported as a consequence of long standing inflammatory bowel disease.7 The authors concluded that chronic colitis could also cause melanosis coli without laxative abuse. More importantly, clinicians should be aware of other causes of blackening of the colonic mucosa, e.g. cell necrosis. Melanosis coli had been misdiagnosed as ischaemic colitis resulting in unnecessary colostomy.8 Incidence Melanosis coli seems to be prevalent world-wide. A Medline search reveals articles on this topic in seven languages. The reported incidence of melanosis coli varies greatly in different countries depending on the prevalence of chronic use/abuse of anthraquinone laxatives in that locality. Factors favouring laxative abuse are culture-related, and include misconceptions on constipation, "colonic toxins", and distorted body image among the lay population. The family physician is in a unique position to educate the public and to rectify these misconceptions. In general, the prevalence of melanosis coli in a population tends to increase with age.9 However, it has been reported in a child as young as four years of age.10 The author is not aware of any local statistics on this condition, but is of the impression that melanosis coli is by no means uncommon in colonoscopies performed locally. Endoscopy features Endoscopically, the colonic mucosa appears brownish-black. The pigmentation extends for various lengths along the colon, imparting the colon an "alligator skin" appearance (see photo). The presence of the dark pigment provides a natural form of chromoscopy which allows pit patterns of the colon to be seen quite easily. In addition, since the pigment is not deposited in dysplastic tissue,11 tumours and polyps will stand out quite prominently against the black background of the otherwise normal mucosa. This will make visual detection of small polyps relatively easy (Figure 1). Lipofuscin pigmentation will not involve the everted small intestinal mucosa of the ileal-caecal valve, which also stands out prominently against the background of black colonic mucosa (Figure 2).

These colonoscopy photos were taken from a 68 year-old Chinese bone setter, who had been taking a patent Chinese herbal laxative for many years for dyschezia. His entire colon appeared black at colonoscopy. The condition develops after months of prolonged ingestion of anthraquinone containing laxatives. The colon will eventually revert to its original pinkish colour 3 to 6 months after stopping the laxatives. Cancer risk The increase in apoptosis of colonic mucosa by anthraquinone laxatives was thought to lead to increased risk of colonic cancer by some workers.12 However the overwhelming data, including large scale retrospective13,14 and prospective15 studies, is in support of the conclusion that melanosis coli is not associated with increased cancer risk. The apparent increase in the incidence of adenomas is probably due to easier detection of small adenomas against the black background,13 as illustrated. Conclusion Melanosis coli is a condition in which the colonic mucosa turns brown-black by the deposition of lipofuscin, commonly after prolonged abuse of anthraquinone laxatives. It is not associated with increased cancer risk and is by and large a benign and reversible condition. Family physicians should be on the watch for patients with abdominal complaints. Such patients may well be candidates for laxative abuse, a fact often denied or concealed by patients. Key messages

A C W Mui, MBBS(HK), MRCP(UK), FRCP (Glasg), FHKAM(Med)

Specialist in Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Department of Ophthalmology, United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr A C W Mui, Room 1505, Sino Centre, 582-592 Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

||||||||