|

May 2003, Volume 25, No. 5

|

Update Articles

|

|||||||

Prescribing exercise for the elderlyK S Ho 何健生 HK Pract 2003;25:204-212 Summary We are facing an ageing population whose activity level will gradually decline. Exercise has been shown to be beneficial for the elderly not only in improving exercise capacity and modification of coronary risk factors, but also in other aspects of health such as social functioning, psychological well being and fall prevention. Family physicians should take efforts to counsel every elderly individual on exercise. After careful assessment and identification of risks, prescribing exercise for the elderly is safe. 摘要 我們面對人口老化的問題,老人的活動能力越來越差。運動不但可改善老年人的運動能力, 改進冠心病的危險因子,而且提高他們的社會功能,心理健康,還可防止跌倒。 家庭醫生應盡為每位老年人提供運動方面的專業建議。細心檢查評估風險後,建議老年人做運動是安全的。 Introduction Regular exercise has been shown to decrease mortality and age related morbidity in older adults.1,2 However, in the United States, up to three quarters of the older adult population do not currently exercise at recommended levels, and only 30% of those aged 65 and older report any regular exercise.3 In Hong Kong, the Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence study on people aged between 25 and 74 years showed that about 60% of them did no exercise over a 1-month period. Approximately one third reported doing exercise to the levels recommended by the guidelines.4 Data from Elderly Health Services of Department of Health revealed that about 15% of their community dwelling members did not do any sort of exercise at all.5 By 2031, 24.3% of our population will be aged 65 and above, amounting to 2.4 millions. Since activity level generally declines with advanced age, the absolute number of inactive older Hong Kong people is likely to rise dramatically if we do not do something about it. Benefits of exercise Increasing exercise may have more "health" benefits than actual "fitness" benefits. Fitness is related to a person's maximal capacity and has been linked to lower mortality rate. However, exercise can improve health even though a person does not achieve maximum fitness. It improves cardiac function, functional capacity, psychosocial well-being, mental status and modifies coronary risk factors. Risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) that can be improved through exercise include hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, hyperinsulinaemia, glucose intolerance and obesity. Subgroup analysis of the Harvard alumni study found that modest increase in life expectancy was possible even in those who did not begin regular exercise until age 75.6 Another benefit of exercise training for older women is an increase in bone mineral density (BMD). The psychosocial factors related to frailty and functional decline include depressive symptoms, social isolation and low self-esteem. Exercise has been shown to improve depressive symptoms, morale and social function. However, exercise for the elderly is seldom considered either by the older adults themselves or by some health care providers.7 Threshold for aerobic training There are 4 factors influencing aerobic training response:

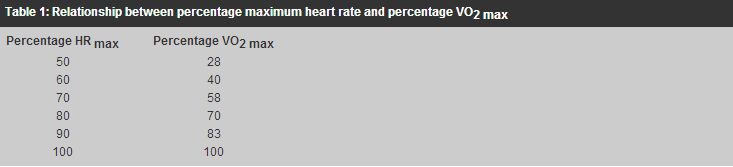

The best index of cardiovascular functional capacity is the maximum oxygen uptake or VO2 max. VO2 max is the maximum rate at which the body can utilize oxygen. Guideline for exercise establishes aerobic training intensity via direct measurement (or estimation) of VO2 max and heart rate maximum or HR max and then assigns an exercise level corresponding to some percentage of the maximums. Heart rate has been used as an alternative to classify exercise for relative intensity when establishing a training protocol. Percentage VO2 max and percentage HR max relate in a predictable way regardless of gender, age and exercise mode. (Table 1)

As a general rule, aerobic capacity improves if exercise intensity regularly increases heart rate to at least 50 to 70% of the maximum. An alternative and equally effective method of establishing the training threshold, termed the Karvonen method (or heart rate reserve method) is to exercise the subject at a heart rate equal to 60% of the difference between resting and maximum:8 60% HR reserve = HR rest + 0.60 (HR max - HR rest) Maximum heart rate computes as 220 minus the person's age in years: HR max = 220 - age(y) The intensity of exercise needed to attain health related benefits may differ from what is prescribed for cardio-respiratory fitness. Lower levels of physical activity have been shown to reduce the risk of certain chronic degenerative diseases and yet be insufficient to improve VO2 max. For most de-conditioned adults with or without CAD, the threshold intensity for exercise training lies between 40% and 50% of the oxygen uptake reserve or heart rate reserve:9 40-50% Heart Rate Reserve = HR resting + 40-50% (HR max - HR resting) Endurance exercise training for the elderly Recent studies indicate that older people can increase VO2 max with endurance exercise training to the same relative degree as young people.10,11 The American College of Sports Medicine recommended that in older healthy adults, an exercise frequency of 3 to 5 days a week, a training intensity of 60% maximum heart rate or 50% of maximum heart rate reserve for 20-30 minutes might improve cardiovascular fitness. Accumulation of thirty minutes per day of single bouts at least 10 minutes long is equally effective. Exercise prescription Exercise prescription for older adults may be a challenging task for primary care physicians. Factors to consider include heart disease, medications that alter heart rate or blood pressure responses, osteoarthritis, painful feet, insensitive feet, and claudication. Men and women without orthopaedic or other limitations may be able to walk briskly, cycle, dance or even jog. For those who are unfit, simple range-of-motion exercises, stretching exercises, or slow walking may be appropriate. There are 4 types of exercise training for the older individuals, namely:

In general, all four types should be recommended. For those who are physically well, more emphasis is given to aerobic training. For those who are frail, more emphasis is on resistance training, balance training and flexibility training (Figures 1 and 2). The goals of exercise are to prevent cardiovascular disease, minimise biological changes of ageing, reverse disease syndromes, control chronic diseases and improve psychological health and mobility.

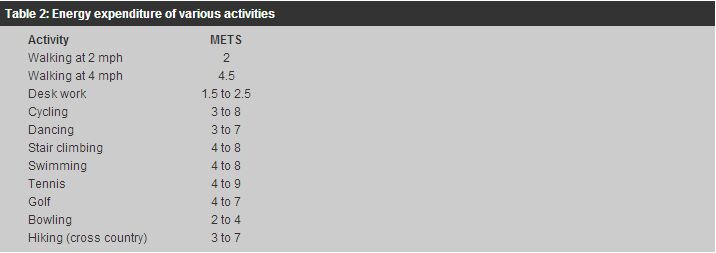

1. Aerobic exercise Jerome Fleg,12 Director of the Laboratory of Cardiovascular Science at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland emphasised that increasing exercise may have more "health" benefits than actual "fitness" benefits for the elderly. Programme for them should start with lower intensity exercise and advance in small increments. A common misconception is that exercise must be performed at high intensity for therapeutic effect. In fact the intensity of an aerobic exercise programme to improve cardiovascular conditioning should focus on long term sustainability and enjoyment to achieve an optimal overall outcome.13 It has been shown that training at about 40-50% of maximum exercise performance does not appear to be less effective than training at 70% of maximum of exercise performance. Heart disease is not a contraindication to exercise in most circumstances and age per se is not a contraindication to endurance exercise.14 Moderate exercise is defined as physical activity that is well within a person's current capacity; the person should be able to sustain the activity for prolonged periods, generally at an intensity of 40 to 60 percent of cardiorespiratory capacity. The main activity period should include 20-30 minutes of cardiorespiratory conditioning. De-conditioned elderly should begin exercise at lower intensity level, e.g. 40% of the respiratory capacity. A warm-up period and a cool-down period of five to ten minutes each should be included. For most older adults, moderate activity corresponds to 2.5 to 5.5 metabolic equivalents (METS), which is equivalent to level walking at 2.0 to 4.5 mph pace. (Table 2)

The selection of exercise programme should be individualised, and is based primarily on the level of fitness and factors such as strength, flexibility and painful joints. For most well elderly subjects, walking, cycling leisurely, playing golf and swimming with moderate effort with energy expenditure equivalent to 2.5 to 5.5 METs are recommended. Although treadmill testing is the most popular and best-evaluated form of testing for aerobic fitness, a simple walking test may be used for the elderly. There is a close relationship between perceived exertion and VO2 uptake.15 The perceived exertion scale as designed by Borg16 rated perceived exertion from 1 to 20. Scale of <10 is classified as very light and >16 as very heavy. Scale 10-11 is classified as light and its relative intensity is equivalent to HR max 52-60% or VO2 max 31-50%. Scale 12-13 is classified as moderate (somewhat hard) and is equivalent to HR max 61-85% or VO2 max 51-75%. The patients may be asked to exercise to maximum intensity at which they are still able to comfortably carry on a conversation (the "talk test") without undue shortness of breath or chest discomfort. This may require some trial and error for the patients. Warm-up and cool-down periods consisting of five to ten minutes of less intense activity should be included. For unfit patients, they may benefit from shorter and more frequent bouts of exercise initially.17 2. Resistance training Muscle strength declines by 15%-30% per decade after age 70 years, but resistance training can result in huge gain and improve functional performance for elders.18 It can be beneficial in the prevention and management of chronic conditions such as low back pain, susceptibility to falls and impaired physical function in frail elderly persons. The Advisory Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association has issued guidelines on resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease.19

In resistance training, there may be a slight increase in cardiac output and some

vasoconstriction. This may cause a disproportionate rise in systolic, diastolic

and mean blood pressure, hence increasing demand on the heart.20 Although

isometric or combined isometric and dynamic (resistance) exercise has traditionally

been discouraged in patients with coronary disease, it appears that mild to moderate

resistance exercise is less hazardous than was once presumed, particularly in patients

with good aerobic fitness and normal or near-normal left ventricular systolic function.

Numerous investigations in healthy adults and low-risk cardiac patients (i.e. patients

without resting or exercise-induced evidence of myocardial ischaemia, severe left

ventricular dysfunction, or complex ventricular dysrrhythmias, absence of anginal

symptoms, ischaemic ST-segment depression, abnormal haemodynamics, and uncontrolled

hypertension of systolic pressure

Resistance training can include elastic bands of various tensile strength, as well as metal dumb bells or plastic-formed weights of around 2 lbs filled with water or sand.22 Using weight in the form of hand-held drinking bottles filled with water is a convenient option for outdoor exercise. Weights can be increased up to 3 to 4 lbs progressively for the relatively fit elders. Simple exercise such as repeated rising from a chair can help to train up major muscle groups of the lower limbs. Proper breathing during resistance training is important and should be performed as follows: exhale during lift for 2 to 4 seconds and inhale during lowering of weight for 4 to 6 seconds, and work through the entire range of movement (or as tolerated for those with arthritis). Valsalva maneuver should be avoided. The lifts should be separated by 1 to 2 seconds of rest with 1 to 2 minutes rest between sets. Warm-up and cool-down activities should accompany the exercise. The muscle groups include hip extensors, knee extensors, ankle plantar flexors and extensors, biceps, triceps, shoulders, back extensors and abdominal muscles. 3. Balance training There is empirical evidence that balance programmes can improve stability and decrease risks of falls.23,24 Balance training activities include Tai Chi movement, standing yoga posture, standing on one leg, heel to-toe standing and walking, stepping over objects, climbing up and down steps and standing on heels and toes. It can be done 1-7 days per week with 1 set per day of 4 to 8 different exercises with about 10 repetitions each set. 4. Flexibility training Stretching major muscle groups once per day after exercise when muscles are more compliant to a maximum pain-free distance and hold, with four repetitions per day, 30 seconds per stretch, on 6 to 10 major muscle groups are recommended. Stretching exercises typically include shoulder flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation; elbow flexion; hip flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation; plantar flexion and dorsiflexion; and ankle inversion and eversion. Exercise for the frail elders For frail elders, the traditional elements of exercise, i.e. mode of exercise, intensity of exercise and frequency of exercise can be applied. However, exercise intensity should focus on establishing an upper level of endurance rather than a specific threshold, hence achieving a target heart rate may not be necessary. The mode of exercise for frail elders depends on preserved functional skills and pain-free range of motion. Aerobic conditioning of mild to moderate intensity should follow strength and balance training. Aerobic training can begin, first by reaching a target frequency (i.e. 3 days per week), then duration. Walking is a good exercise for the frail elders. Assisted devices may be used to increase safety. In some individuals arm and leg ergometry, seated stepping machines and water exercise may be needed because of various disabilities. Patient should be counselled to discontinue exercise and seek medical advice if they experience any major warning signs or symptoms e.g. chest pain, palpitation or light-headedness. Contraindications The contraindications to exercise in the elderly are not different from those applicable to younger adults. Acute illnesses, unstable chest pain, uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension or other metabolic diseases are absolute contraindications. Other conditions in this group include recent changes on ECG and myocardial infarction, third degree heart block, acute congestive heart failure, severe aortic stenosis and inoperable enlarging aortic aneurysm. Relative contraindications include cardiomyopathy and complex ventricular ectopic. During treatment of hernia, cataract or retinal bleeding, temporary avoidance of certain kind of exercise is recommended.19,23 (Table 3)

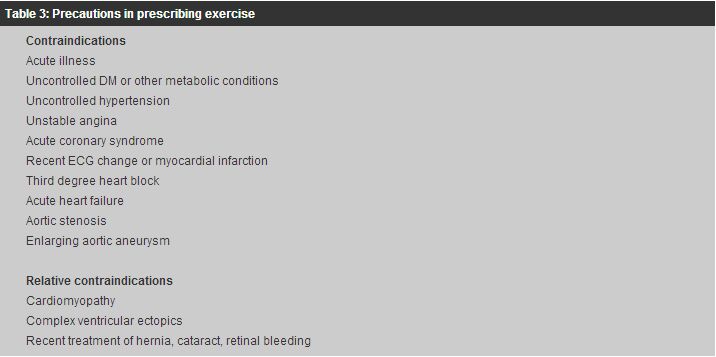

Exercise promotion There are many ways to promote exercise for the elders. The "stage of change" model is often used to promote positive behaviours. The most successful compliance with long-term exercise is likely to be accomplished by identifying and overcoming barriers to activities, setting individualised and specific goals, involvement of family carer and spouse, and providing positive reinforcement.25 The exercise programme should be fun, social and sustainable. Music and dancing can be added to the programme. Exercise can be promoted in groups and involve partners. To make it sustainable, exercise can also be prescribed for brief, dedicated time periods daily. Limited equipment and exercise space are often cited as reasons for not exercising by some elderly people. Other common barriers include lack of time, lack of a safe place to exercise, fear of injury and lack of a partner. However, study showed that it is easier for older adults to overcome environmental barrier than to overcome will power barriers to exercise. Therefore, physicians' advocacy is an important element for success. As for environmental barriers, physicians can advocate adapting the exercise to the setting and daily routines of the older adults. For frail elders, exercise can take place in the home, senior social centres, or institutional living setting. Understanding a patient's personality is also helpful. Whether patients are extroverted or introverted will greatly affect their compliance with a group exercise class versus a home programme. Safety Exercise imposes certain risks and this can be avoidable with careful screening and monitoring. The literature on exercise training in the frail elderly showed no reports to date of serious cardiovascular incidents or exacerbation of metabolic problems. Resistive exercise training have incurred some exacerbations of a pre-existing hernia and underlying arthritis and this requires modification of the exercise prescribed. It has been reported that aerobic exercise at low-to-moderate intensity or weight lifting at moderate intensity, if begun gradually and progressed slowly, is unlikely to cause cardiovascular symptoms in patients with stable disease.26 The pre-exercise medical history should include cardiovascular risk factors, past and current musculoskeletal injuries, previous activity pattern, medications with potential for interaction with exercise prescription e.g., beta blockers, sympathomimetics, insulin and oral hypoglycaemics; and any chronic disease especially CAD. Pre-exercise physical examination should include cardiovascular and musculo-skeletal systems, assessment of mobility and balance, evidence of peripheral vascular disease and abdominal aortic aneurysm, presence of inguinal hernia and retinal disease. For prescription of endurance training exercise aiming at 60% VO2 max such as jogging and running, which is not commonly required for the elderly, exercise stress test is recommended for patients with two or more coronary risk factors, diabetes, or known coronary artery disease or cardiac symptoms. Conclusion As our population of older adults increases, it will be very important for family physicians to counsel our sedentary patients to become physically active. Exercise has a beneficial effect on numerous aspects of health, and it should be encouraged at all physician visits. An exercise prescription specific for the individual can be given, and the components should include exercise type, intensity, dose and frequency. All four types of exercise should be considered where appropriate, although morning walk and Tai Chi may be beneficial. The exercise should be catered for individual needs, preferably should be fun and social, and above all, should be sustainable. Reference materials on this topic are available from the website of Elderly Health Services of Department of Health.27 Acknowledgement I am indebted to Mr. Kelvin Li Tung-yu, physiotherapist of Elderly Health Services of Department of Health for his expert input and comments on this article. Key messages

K S Ho, FHKAM(Medicine), FHKAM(Family Medicine)

Consultant (Family Medicine), Elderly Health Services, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Dr K S Ho, Room 3502, 35/F, Hopewell Centre, 183 Queen's Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong.

References

|

||||||||