|

November 2003, Volume 25, No. 11

|

Original Article

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Effects of SARS on consultations in primary care in Hong Kong

R S Y Lee

HK Pract 2003;25:532-541 Summary

Objective: To study the infection control measures and concerns

in primary care practices, and the effects of SARS on primary care consultation

using the Leicester Assessment Package (LAP) criteria during the SARS episode in

Hong Kong.

Keywords: SARS, consultation, primary care. 摘要

目的: 研究香港SARS流行期間基層醫療醫生的感染控制措施和擔心,及應用Leicester評估工具(Leicester Assessment

Package, LAP)研究SARS對基層醫療接診的影響。

Introduction Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is an acute respiratory illness caused by infection with the SARS virus. In March 2003, more than 50 hospital healthcare workers in Hong Kong were identified as having a febrile illness and eight developed x-ray signs of pneumonia.1 Since then SARS has dominated the headlines in Hong Kong newspapers. Failure to detect the presence of bacteria and viruses known to cause respiratory disease suggested that the causative agent was a novel pathogen. A new coronavirus was later isolated from patients with SARS.2 The virus disseminated largely by droplet spread and could be contracted through close contacts with or unprotected exposure to those infected, such as in a health care setting or household. Although SARS infected mainly hospital healthcare workers, a few primary healthcare workers were infected in Hong Kong as well. To prevent SARS and other droplet infections in their clinics, the Department of Health issued a supplement to their "Guidelines on infection control practice in the clinic setting" on droplet and contact precaution. The precautions included mandatory hand washing, wearing of a surgical mask and protective clothing within clinic areas, wearing of gloves when in contact with blood, body fluids or secretions, patient triage and defining high-risk areas in the clinic.3 Similar precautions were also adopted already by many primary care clinics although individual implementation might differ due to practicability in different types of practice. The SARS epidemic affected 1,755 individuals, including 300 deaths in Hong Kong.4 On June 23, 2003, after more than three months of battling with SARS, Hong Kong was removed from the list of SARS affected areas and declared healthy and safe for travellers by the World Health Organisation. The objectives of this study were to study the infection control precautions and concerns in primary care practice, as well as the effects of SARS on primary care consultations using the Leicester Assessment Package (LAP) criteria during the SARS episode in Hong Kong. Methods All full members and fellows of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians were surveyed by postal questionnaire (a copy of the questionnaire can be obtained from the author upon written request) in July 2003 when the SARS outbreak was over. Overseas members and fellows were excluded. A pilot survey was performed on 20 fellows in mid June 2003. The questionnaire consisted of 18 questions in three parts. Part 1 (questions 1-5) gathered demographic data concerning the respondents. Part 2 (questions 6-15) explored their infection control precautions and concerns during the SARS episode. Part 3 (questions 16-18) assessed the effects of SARS on their consultation skills using the LAP.5 LAP is an integrated consultation skills assessment tool whose criteria of consultation competence have been validated both in the United Kingdom6 and in Hong Kong.7 It contains 39 component consultation competences in seven consultation categories, namely: interview/history taking, physical examination, patient management, problem solving, behaviour/relationship with patients, anticipatory care and record keeping. Descriptive results were represented as percentages. Univariate analysis using the Chi squared test was performed to determine whether any factors in Part 1 influenced the infection control precautions and concerns of primary care physicians in Part 2. Multivariate analysis was then repeated using multiple logistic regression with backward stepwise procedure to explore significant factors as appropriate. The cut-off point of entry of multiple logistic regression was fixed at 0.05 and the cut-of point of exclusion at 0.10 for the probability values. A two-sided 5% level of significance is considered significant for the statistical tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for windows version 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago III). In question 16 of Part 3, scores 1 to 5 were allocated to each LAP consultation component: 1= much easier, 2= a little easier, 3= not at all affected, 4= a little more difficult and 5= much more difficult. The mean scores were calculated for each consultation component to assess the degree to which it was affected. As a score of 3 was considered neutral, a mean score in either direction from 3 showed the trend was either easier if less than 3, or more difficult if greater than 3. The non-parametric Sign test was employed to detect any significant trend in the respondents' feelings towards each consultation component. The mean of the mean scores of each consultation component in a category represented the degree to which that category was affected. Qualitative data on how other aspects of consultations were affected was explored in question 18 of Part 3. Results A total of 318 questionnaires were returned at the end of the survey period. The response rate was 60%. The respondents' demographic profiles are shown in Table 1. The infection control precautions and concerns of respondents are summarised in Table 2. One of the significantly (p<0.05) associated demographic factors is the type of practice. Comparison between public and private practices is summarised in Table 3. 71.4% respondents (84.7% public practices and 68.0% of private practices; p=0.01) triaged their patients. More public (87.4%) practices triaged their patients than private practices (68.0%); p=0.01. 63.9%, 39.6% and 28.2% of those who carried out initial screening/triage triaged by nurses, doctors and receptionists respectively. More public practices (78.0%) triaged by nurses than private practices (49.0%); p=0.02, but more private practices (49.0%) triaged by doctors than public practices (6.0%); p=0.02. 85.9% respondents took the temperatures of their patients (85.9%). More private practices (95.3%) took temperatures than public ones (58.0%); p<0.01. Other means of triage reported were patients' self-reporting of fever (69.2%), contact (69.2%) and symptoms (62.6%), travel history and history of hospital visits. For triaged patients suspected of SARS, 87.1% respondents asked the patients to wear a surgical mask, 61.3% saw them first, 60.1% kept minimal contact time, 34.9% put them in a separate waiting area and 28.0% saw them in a designated room/area. More public (74.6%) than private practices (23.3%) put triaged patients in a separate waiting room (p=0.03), and saw them in a designated consultation room (public 67.8%, private 16.4%; p=0.03).

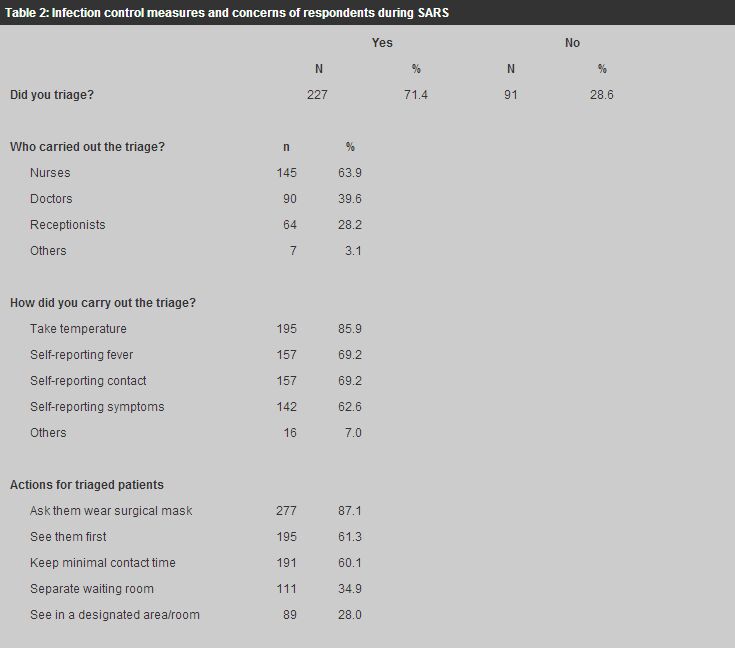

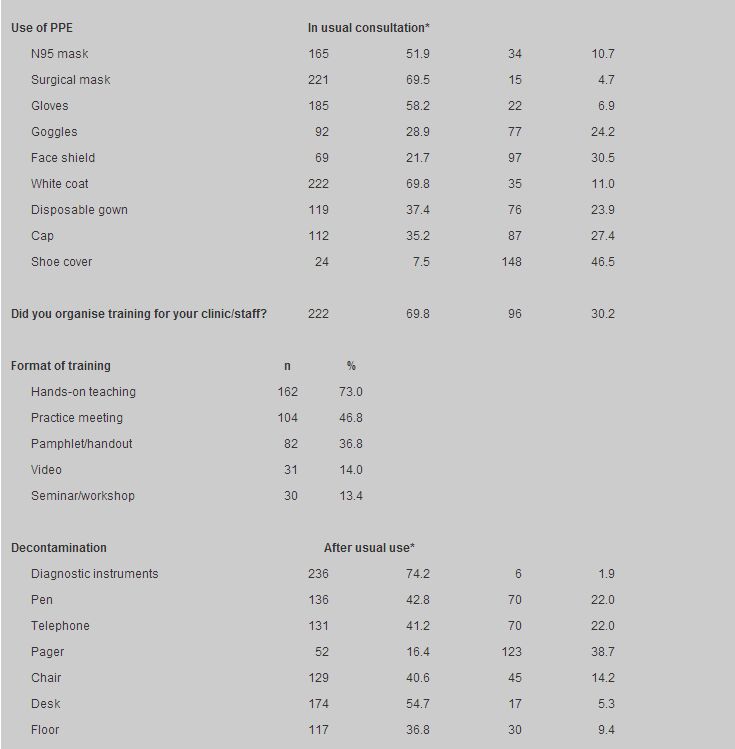

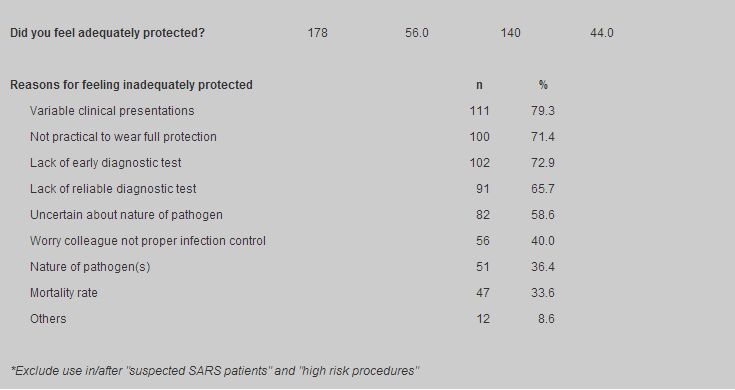

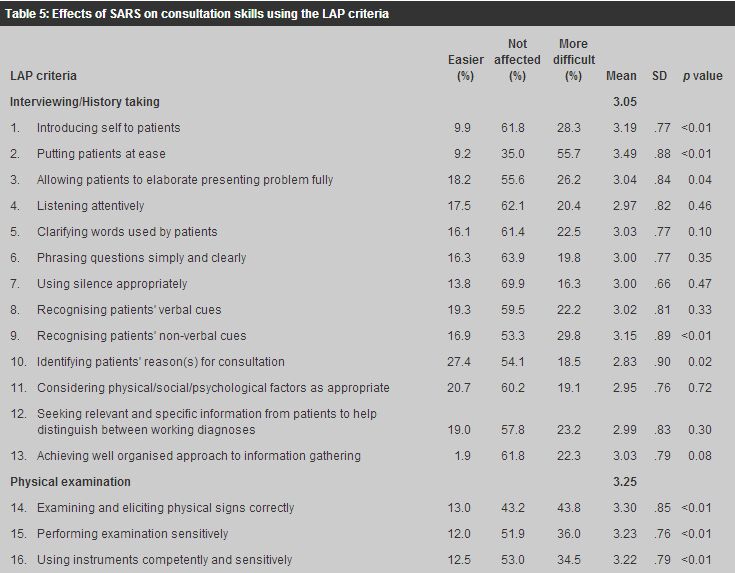

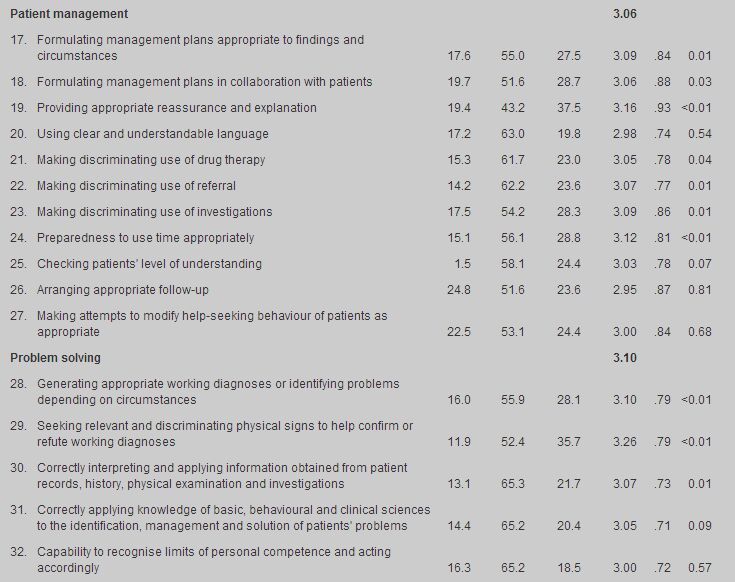

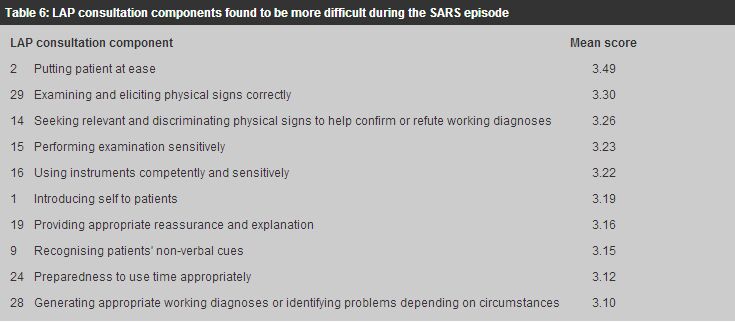

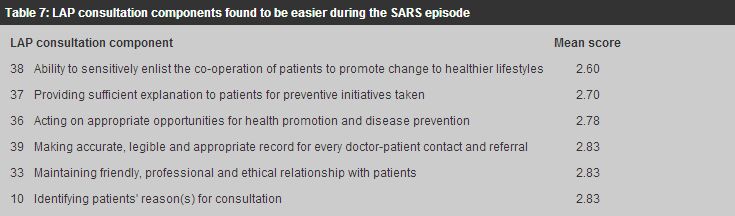

In the use of personal protection equipment (PPE), goggles, disposable gown, cap and shoe cover were used more by respondents working in public practices. All respondents wore either a N95 or surgical mask during consultation. N95 masks were used in high-risk procedures. There were 69.8% of respondents who organised training for their clinic staff. There was no association between whether training was organised and the type of practice but the format of training varied with the type of practice. The format of training included hands-on teaching (73.0%), practice meeting (46.8%), pamphlet/handout (36.8%), video (14.0%) and seminar/workshop (13.4%). 82.2% of private practices and 85.5% of solo practices which organised training provided hands-on teaching while only 41.5% of public and 72.2% of group practices did so; p<0.01 and p=0.03 respectively. 32.7% and 61.1% of group practices organised practice meetings and used pamphlet/handout for training while 3.3% and 16.7% of solos practices did so; p=0.03 and p=0.04 respectively. Public practices trained more by video (85.5%) and seminar/workshop (48.8%) as compared to private practices (35.5% and 5.2% respectively), p<0.01. Most respondents regularly decontaminated the diagnostic instruments and furniture in the clinic. Fifty-six percent felt adequately protected by their infection control measures but 44.0% did not. More fellows of HKAM (68.4%) felt adequately protected than non-fellows (50.5%); p<0.01; and more public doctors (69.5%) felt adequately protected than private ones (53.4%); p=0.02. The major concerns were the variable clinical presentations of SARS (79.3%), the impracticality of wearing full protection (71.4%) and the lack of early (72.9%) and reliable (65.7%) diagnostic tests. (Table 2) More private doctors (77.5%) found it not practical to wear full protection than public ones (44.4%); p=0.01. The proportions of consultations with consultation skills affected by SARS are summarised in Table 4. 58-67% respondents reported their consultation skills were affected in less than 25% in different categories of their consultations. The effects of SARS on consultation skills are summarised in Table 5. 50-60% respondents found the 39 LAP consultation components not affected at all. Among those affected, 16 components became more difficult and six became easier. The more difficult and easier consultation components are summarised in Tables 6 and 7, in descending order.

Among the seven consultation categories, history taking, physical examination, patient management and problem solving were found to become more difficult while relationships with patients, anticipatory care and record keeping became easier. No association was found between the demographic factors in Part 1 of the questionnaire and the effects of SARS on consultation skills. In question 18 regarding how other aspects of consultations were affected, many respondents reported an initial surge in patient attendance followed by a significant drop. More stringent infection control measures led to increased work and expenditure. Some patients and clinic staff suffered from anxiety and disturbed mood and some became more prone to give antibiotics for fever cases. Many reported improved relationships with patients during the SARS episode. Discussion The variable clinical presentations of SARS were the major concern among the respondents. Uncertainty and lack of diagnostic tools to confirm or refute the diagnosis, especially in the initial stages of the SARS episode, made reassurance (LAP components 2 and 19), physical examination with the interpretation of physical signs (LAP components 14,15,16 and 29), and diagnosis (LAP component 28) more difficult. Wearing a mask was uncomfortable and obscured facial expression. Communication with patients was therefore compromised (LAP components 1 and 9) and affected time management (LAP component 24) since more time was needed for reassurance and communication, although minimising waiting and contact time of patients in the clinic was deemed to be desirable to prevent cross-infection. Anticipatory care (LAP components 36-38) was found to be easier as patients became more health conscious. Some respondents found patients became more compliant with medical advice, and were more considerate e.g. they covered their mouth when coughing. The media and the general community were appreciative of the dedication and work of healthcare workers during this critical period. These factors may have contributed to an improved doctor-patient relationship (LAP component 33). Use of PPE is most effective in infection control if it is coupled with defining "clean" and "high risk" areas and restricting the flow of people across the two areas. In many primary care clinics, the staffs are multi-skilled; they may be chaperones for doctors in the consultation room and also cashiers at the counter. Changing the whole set of PPE each time when moving across different areas was not practical. Respiratory symptoms with or without fever are among the most common reasons for patients consulting primary care doctors except in some government general outpatient clinics where chronic diseases constitute the majority of workload. Triage by taking temperatures was therefore much more meaningful than triage by self-reporting of symptoms and fever. Putting the triaged patients in a different waiting room and seeing them in a designated consultation room were also not practical, not only due to the limitation of space but also due to the nature of complaints with which patients presented. Many respondents therefore reported regular decontamination of diagnostic instruments, furniture and floor every few hours as a routine measure instead of after "high risk" consultations. An important factor affecting the respondents' choice of infection control precautions and equipment was their type of practice. Public and group practices incorporated more division of labour, while private and solo practices offered more personalised and individual care. Public practices carried out more triage. The triaged patients were put and seen in separate waiting and consultation rooms. They used more video and seminars/workshops in training. Private practices took temperatures for triage and provided hands-on training for their staff. Even with the introduction of all these infection control precautions, 44% of respondents still felt inadequately protected. The major concerns were the variable clinical presentations of SARS, the practicability of wearing full PPE, uncertainty about the nature of the pathogen, and the lack of early and reliable diagnostic tests. The limitations of the study were that the study population included only full members and fellows of the HKCFP, and response to the postal questionnaire was voluntary. People who chose to respond may be different from those who did not. Therefore the respondents may not be representative of all primary care physicians in Hong Kong. Conclusion The period between March and June 2003 was a most challenging time for primary care physicians in Hong Kong. There were anxieties, uncertainties, increased work and expenditure. However, not only have more stringent infection control measures appropriate to the type of practice been implemented in many primary care clinics, patients are now more aware of, and responsive to, the important contribution that anticipatory care i.e. disease prevention and health promotion can make to their well-being. The major concerns of physicians were the variable clinical presentations of SARS, uncertainty about the nature of the pathogen, and the lack of early and reliable diagnostic tests. Improved communication and sharing of information among all disciplines of our profession and development of better diagnostic tools for primary care use will improve patient care and infection control in future if SARS recurs. Key messages

R S Y Lee, MBBS, MPH, FHKCFP, FHKAM(Family Medicine)

Chairman, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. R C Fraser, CBE, MD, FRCGP, FHKCFP Professor of General Practice, University of Leicester, UK, Honorary Advisor, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. C L K Lam, MBBS, FRCGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Associate Professor, Family Medicine Unit, The University of Hong Kong, Honorary Advisor, Research Committee, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. K S Ho, MBBS, FHKCFP, FHKAM(Medicine), FHKAM(Family Medicine) Consultant (Family Medicine), Elderly Health Services, Department of Health. D K T Li, MBBS, FHKCFP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) President, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians. Correspondence to : Dr R S Y Lee, Aberdeen Elderly Health Centre, 10 Reservoir Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong.

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

, R C Fraser, C L K Lam 林露娟, K S Ho 何健生, D K T

Li 李國棟

, R C Fraser, C L K Lam 林露娟, K S Ho 何健生, D K T

Li 李國棟