|

November 2003, Volume 25, No. 11

|

Update Articles

|

Infective endocarditisA C K Lam 林超奇 HK Pract 2003;25:551-561 Summary Infective endocarditis carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality. Rapid diagnosis, effective treatment and prompt recognition of the various complications are essential to a good patient outcome. Infective endocarditis often presents in an occult fashion, and its early diagnosis depends on one having a high index of clinical suspicion; especially in patients with congenital heart disease, prosthetic valves, or a previous episode of infective endocarditis. Sadly, our clinical experience shows that patients who are the sickest are often referred late for imaging and specialist care. Paradoxically, echocardiography departments are often swamped with imaging requests for patients in whom this diagnosis is unlikely.1 摘要 傳染性心內膜炎的發病和死亡的風險很高。快速的診斷,有效的治療和及早察覺併發症對治療結果有重要影響。 傳染性心內膜炎時常以不明顯的徵狀出現,早期診斷主要依靠臨床醫生的警覺性,尤其是有先天心臟病, 人造瓣膜和曾有傳染性心內膜炎病史的病人,患病機會很高。但實際情況, 一些嚴重的病人未能及時轉介進行造影檢查和轉介專科治療,而超聲心電圖檢查機會卻常常為染病機會不大的病人佔用了。 Introduction Infective endocarditis (IE), or microbial infections of the endocardium is characterised by fever, heart murmurs, embolic phenomena, anaemia, petechial bleeding and endocardial vegetations that may result in valvular incompetence or obstruction, mycotic aneurysm or myocardial abscess. The characteristic vegetative lesions are composed of a collection of platelets, fibrin, microorganisms and inflammatory cells. The heart valves are the most commonly involved but it could also occur on the chordae tendineae, at the site of septal defect or on the mural endocardium. It has been classified as "acute" or "subacute" on the basis of clinical onset, severity of the clinical manifestation and the progression of the untreated disease. Hartman et al2 reviewed several major risk factors that predispose to valves becoming infected. These include congenital heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, degenerative heart disease, intravenous drug usage, the presence of prosthetic valves, mitral valve prolapse and indwelling catheters. Incidence and epidemiology In Western Europe and the United States, the incidence of community-acquired native valve endocarditis in most studies is 1.7 to 6.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Men are affected about twice as often as women.3,4 The median age of onset of IE has increased from about 35 years in the pre-antibiotics era to the current >50 years. This reflects increased longevity in humans with more patients having degenerative valvular disease, placement of prosthetic valves, diabetes and patients on long-term haemodialysis. There is an increase in nosocomial endocarditis due to more cardiac surgery and other invasive procedures. Infected intravascular devices give rise to at least half of these cases. There is a higher incidence of right-sided endocarditis associated with intravenous drug users (IVDA) and diagnostic/therapeutic procedures requiring vascular lines. Mitral-valve prolapse is a common cardiovascular condition predisposing patients to IE especially in those with coexisting mitral regurgitation or thickened mitral leaflets. Prosthetic-valve endocarditis (PVE) accounts for 7 to 25 percent of cases of IE in most developed countries. PVE develops in 1 percent at 12 months and 2 to 3 percent at 60 months after valve replacement.5,6 It is more common with aortic than mitral valve prosthesis. Early-onset infections (<60 days post surgery) are usually caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci. Late prosthetic-valve endocarditis (>12 months post surgery) are largely community-acquired. The pathogens are usually those seen in native valve endocarditis with a preponderance of viridans streptococci and staphylococci, but with a high incidence of other organisms. Microbiology Overall, viridans streptococci and staphylococci account for about two-thirds of all cases. In some series, staphylococci, particularly staph. aureus, have surpassed viridans streptococci as the most common cause of IE. In addition, coagulase-negative staphylococci, the most common pathogens in early prosthetic-valve endocarditis, have also been identified as an occasional cause of native-valve endocarditis. One species of community-acquired coagulase - negative staphylococcus, staph. lugdunenis is commonly associated with valve destruction and the requirement for valve replacement. The most common streptococci isolated from patients with endocarditis continue to be Strep. sanguis, Strep. bovis, Strep. mutans and Strep. mitis. IE caused by Strep. bovis is associated with colonic pathology and is more frequent in the older age group.

The enterococci group of organisms form part of the normal gastrointestinal flora.

They are more resistant to antibiotics and are more virulent then viridans streptococci.

There has been an increase in enterococcal endocarditis in the past decade, particularly

in the elderly. The most common species causing endocarditis is

The HACEK group of organisms are fastidious slow growing species that are oropharyngeal commensals and have a predilection for heart valves. The group consists of Haemophilus aphrophilus/paraphrophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens and Kingella kingae. Their presence in blood cultures is nearly always synonymous with HACEK endocarditis. HACEK organisms endocarditis tends to present as large vegetations in native valve, which might be the result of prolonged illness and delay in diagnosis. For other unusually encountered organisms, the approach to the patient with an apparent blood culture-negative IE, Bayer et al7 has written an excellent review and discussion. Symptoms and signs Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) has an insidious onset with low grade fever, fatiguability, weight loss, night sweats, chills, arthralgias and valvular insufficiency. Embolism of vegetations may produce cerebral vascular accident, myocardial infarction, renal involvement with flank pain and haematuria, abdominal pain or acute arterial insufficiency in the peripheral extremity. Physical signs include pallor, fever, new or changing murmurs, tachycardia, petechiae over the upper trunk, conjunctiva, mucous membranes and distal extremities, painful erythematous subcutaneous nodules about the tips of the digits (Osler nodes), splinter haemorrhages under the nails, non-tender erythematous haemorrhagic or pustular lesions often on the palms or soles (Janeway's lesions), haemorrhagic-retinal lesions (Roth's spots - round or oval lesions with small white centres). With prolonged infection, splenomegaly or clubbing of the fingers and toes may also be present. Haematuria and proteinuria may result from embolic infarction of the kidney or diffuse glomerulonephritis due to immune complex deposition. Neurological involvement includes transient ischaemic attacks, toxic encephalopathy, brain abscess and subarachnoid haemorrhage from rupture of a mycotic aneurysm. In acute bacterial endocarditis (ABE), the symptoms and signs are similar but the pace of onset of disease is more rapid. ABE is characterised by the presence of high fever, rapid valvular destruction, valvular ring abscesses, septic emboli, toxic appearance and shock may occur. Prosthetic valvular endocarditis often results in valvular ring abscesses, obstructive vegetations, myocardial abscesses, mycotic aneurysms which can present as valvular obstruction, dehiscence and cardiac conduction disturbances as well as the usual symptoms of SBE or ABE. The high frequency of invasive infection in prosthetic - valve endocarditis results in a higher rate of new or changing murmurs, and of congestive heart failure. Right-sided endocarditis is characterised by septic phlebitis, fever, pleurisy, haemoptysis, septic pulmonary infarction, and tricuspid regurgitation. Diagnosis The diagnosis of IE requires the combination of clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic data. Blood culture is the most important laboratory investigation in the diagnosis of endocarditis. Isolation of the pathogen enables an effective antibiotic treatment regimen to be devised. Blood cultures should be taken prior to any antibiotic treatment is contemplated. If antibiotics have already been given and the patient is clinically stable, delaying empirical therapy for a few days and obtaining additional blood cultures should be considered. It is conventional to take three to five sets of blood cultures within 24 hours to isolate the aetiologic agent and to eliminate the relevance of skin contaminants.

Other abnormal blood results which might be present include an elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and

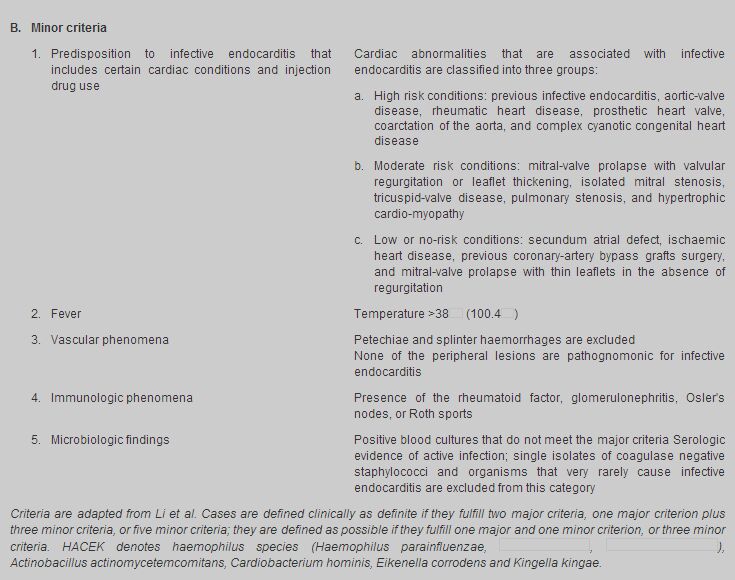

The Duke criteria

In 1994 Durack8 and his colleagues introduced "the Duke Criteria" (Table

1). Major criteria include: (1) a positive blood culture from microorganism

that typically causes infective endocarditis from two separate blood cultures; and

(2) evidence of endocardial involvent documented by echocardiography (definite vegetation,

myocardial abscess, or new partial dehiscence of a prosthetic valve) or development

of a new regurgitant murmur. Minor criteria include: (1) the presence of a predisposing

condition, (2) fever >38

Echocardiography Echocardiography is useful in diagnosis of IE. The sensitivity of transthoraic echocardiography10-12 is between 55% and 65%, and cannot reliably be used for confirmation of endocarditis especially in patients with obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chest-wall deformities. Trans-oesophageal echocardiography12 is 90% sensitive in detecting vegetative growth and is particularly useful for identifying valvular ring abscesses as well as pulmonary and prosthetic valve endocarditis. Complications

The clinical outcome of IE is determined by the degree of damage to the heart, the

location of infection (right- versus left- side, aortic versus mitral valve), whether

embolization has occurred from the infected site, and the immunologically mediated

processes. Damage to infected heart valves is common and quick with both

Embolization commonly occurs in cerebral, myocardial, spleen, kidneys, liver, the iliac or mesenteric arteries. Peripheral emboli may initiate metastatic infections or send septic foci to the arterial vasa vasorum or the intraluminal vessel wall causing mycotic aneurysum. Splenic abscess can be a cause of prolonged fever and may cause diaphragmatic irritation with pleuritic or left shoulder pain. Up to 65% of embolic events in IE involve the CNS, and neurologic complications in 20 - 40% of all patients with IE. The rate of embolic events in patients with IE decreases rapidly after the initiation of effective antibiotic therapy, from 13 per 1000 patient-days during the first week of therapy to <1.2 per 1000 patient - days after two weeks of therapy.13,14 Intracranial aneurysms presentation are often variable. Some patients present with no premonitory symptoms before sudden intracranial haemorrhage. Some aneurysms leak slowly before rupture and produce headache and mild meningeal irritation. Fever in IE often resolves within two to three days after the start of appropriate antimicrobial treatment. The most common causes of persistent fever (more than 14 days) are the extension of infection beyond the valve with or without myocardial abscess, focal metastatic infection, drug hypersensitivity, nosocomial infection or other complications of hospitalisation, such as pulmonary embolism. Treatment

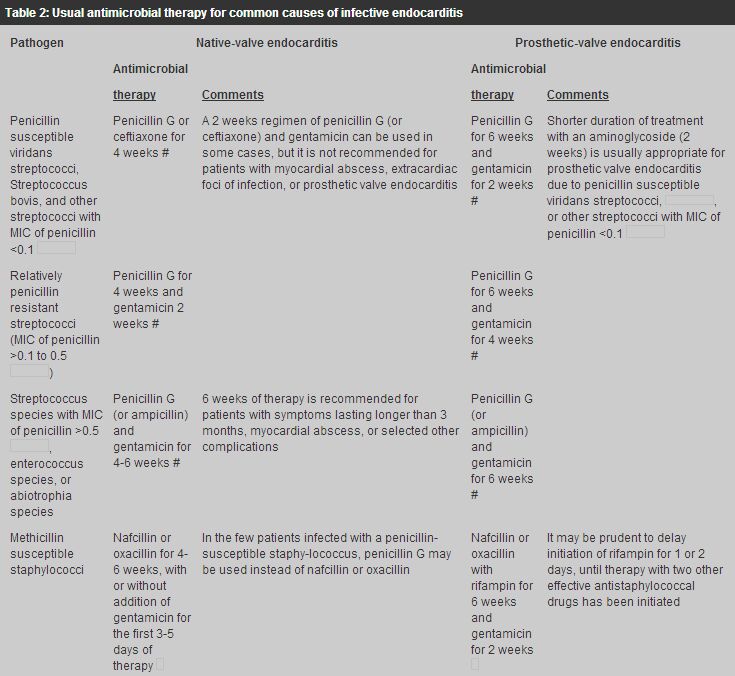

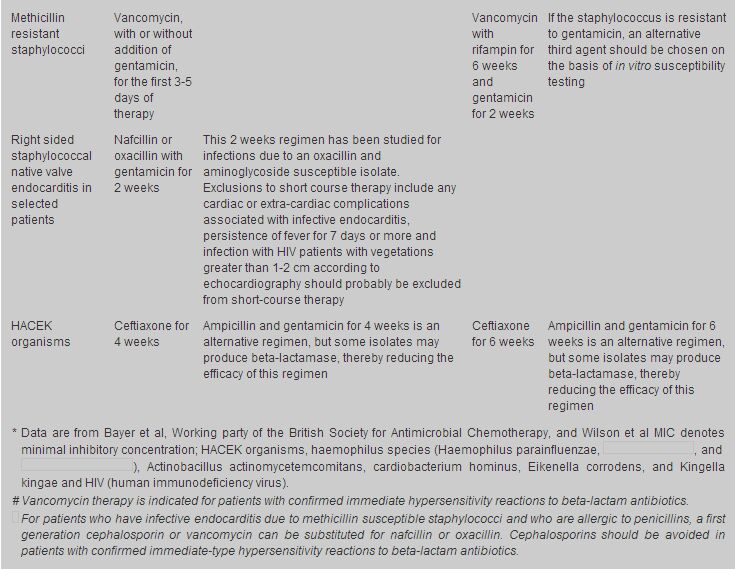

Treatment of the most common causes of IE is summarized in Table 2.

Readers are recommended to look up the Antibiotic treatment for IE due to Streptococci,

Enterococci, Staphylococci and HACEK microorganisms from the American Heart Association.15

For highly Penicillin-susceptible Viridans Streptococci or

For Penicillin-susceptible Viridans Streptococci or

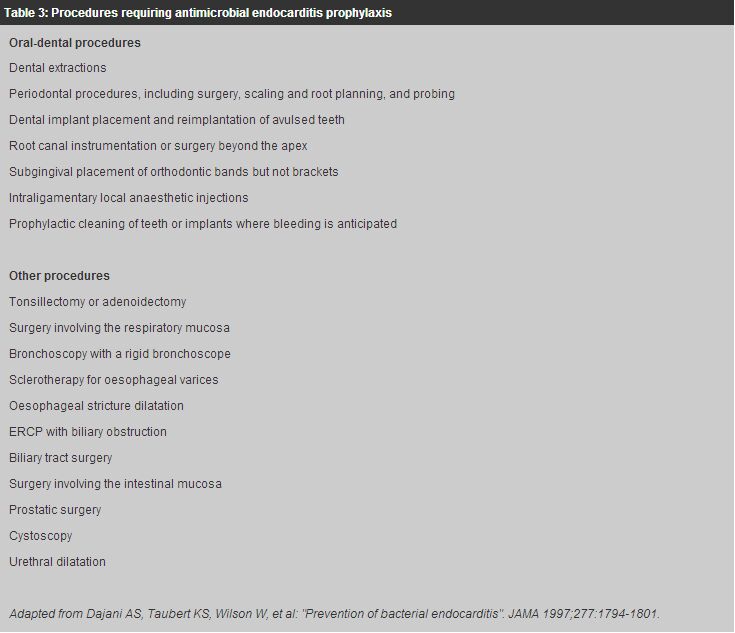

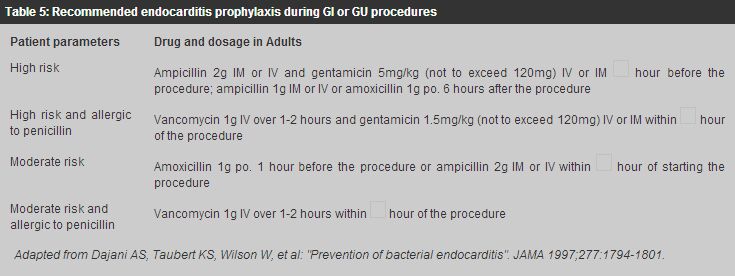

For methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcal endocarditis, IV nafcillin/oxacillin therapy for 4 - 6 weeks together with gentamicin for the first 3 to 5 days of therapy is the usual treatment. For methicillin susceptible Staphylococcal prosthetic-valve endocarditis, IV nafcillin/oxacillin therapy with rifampicin for 6 weeks together with gentamicin for the first 2 weeks is indicated. For methicillin resistant Staphylococcal endocarditis, the optimal antibiotic therapy is vancomycin combined with rifampicin and gentamicin. Vancomycin and rifampicin are administered for a minimum of 6 weeks, with gentamicin use limited to the initial 2 weeks of therapy. Endocarditis caused by HACEK group accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of native valve endocarditis. The drugs of choice for treatment of HACEK endocarditis is ceftriaxone for 4 weeks, and the duration of therapy for prosthetic valve endocarditis should be 6 weeks. Uncomplicated endocarditis in selected stable, compliant patients can be managed by single daily dose of ceftriaxone on an outpatient basis.16-19 This flexible approach is cost effective and permits substantial cost savings in professional time necessary for IV penicillin administration and the risks and inconveniences inherent in any intravascular devices for four weeks. Vancomycin is an effective alternative in patients allergic to penicillins and other-lactam antibiotics. Prolonged IV use of this drug may be complicated by occurrence of thrombophlebitis, rash, fever, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and (rarely) ototoxic reactions. This agent should be infused over at least 1 hour to reduce the risk of the histamine-release "red man" syndrome. Prevention Some cases of endocarditis occur after dental procedures or operations involving the upper respiratory, genitourinary or intestinal tract. Prophylactic antibiotics should be given to patients with predisposing congenital or valvular anomalies who are to have any of these procedures (Tables 3,4,5).

Mortality and relapse Wallace et al20 identified clinical markers, available within the first 48 hours of admission that are strongly associated with in-hospital and six month mortality in patients treated for infective endocarditis.

They are (1) abnormal WBC <3 x 109/1 or >11 x 109/1,

(2) serum albumin <30 gm/1, (3) creatinine level >133

These markers are readily available and should alert practitioners involved to seek an early specialist opinions and possibly early surgery. Netzer et al21 found that independent determinants of event-free survival were infection by streptococci and age <55 years. Long term survival following infective endocarditis is 50% after 10 years and is predicted by: (1) early surgical treatment, (2) age <55 years, (3) absence of congestive heart failure, (4) initial presence of multiple="multiple" endocarditis symptoms. Mylonakis et al22 reviewed the mortality rate among patients with IE and it varies according to the following factors:

The overall mortality rates for both native valve and prosthetic valve endocarditis remain as high as 20 - 25 percent,22 with death resulting primarily from congestive heart failure and stroke. The mortality rate for intravenous drug users with right-sided endocarditis are generally lower, approximately 10 - 30%, depending on the size of the vegetations. Relapse of IE usually occurs within two months of discontinuation of antimicrobial therapy. For native valve endocarditis, penicillin-susceptible viridans streptococcus risk of recurrence is generally less than 2 percent; for enterococcus, 8 to 20 percent. Among patients with IE caused by Staph. aureus, Enterobacteriacae, or fungi, treatment failure often occurs during the primary course of therapy. A positive culture at the time of valve - replacement surgery, particularly in patients with Staphylococcal endocarditis, is a risk factor for subsequent relapse. The relapse rate in prosthetic-valve endocarditis is approximately 10 to 15 percent, and relapse of infection may be an indication for combined medical and surgical therapy.22 Key messages

A C K Lam, MD(Canada), CCFP(Canada), FRACGP(Australia), FHKAM(Medicine)

Honorary Assistant Clinical Professor, Family Medicine Unit, Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong. Honorary Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Community and Family Medicine, Department of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr A C K Lam, Room 1815 East Point Centre, 555 Hennessy Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong.

References

|

|