|

October 2003, Volume 25, No. 10

|

Update Articles

|

Management of common sexually transmitted infectionsManagement of common sexually transmitted infectionsK K Lo 盧乾剛 HK Pract 2003;25:476-484 Summary Sexually transmitted infection (STI) is defined as a heterogeneous group of communicable infections which share one common factor: transmission of infection is mainly through human sexual intercourse. This article provides an update on the management of common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including Gonorrhoea, Non-specific genital infection/Non-gonoccocal urethritis, Genital wart, Genital herpes and Syphilis. Sexually transmitted infection is a silent epidemic world-wide and Hong Kong as an international cosmopolitan city is not exempt. Though treatment for some of the common uncomplicated STIs can be straight-forward, they can be extremely difficult if they are not handled tactfully. The general principle of management and some specific hints for practical management of some common STIs are discussed. 摘要 性病包含多種傳染病,其傳播途徑皆以性接觸為主。本文對常見的性病, 包括淋病、非特異性生殖器感染/非淋菌性尿道炎、生殖器疣、生殖器疱疹和梅毒提供一些最新的處理方法。 性病是一種不被張揚的世界性問題,香港身為大都會,亦不例外。一些常見而簡單的性病,治療上不會有困難, 但若在處理時缺乏技巧,可以弄得困難重重。本文討論處理性病的一般性原則和具體忠告。 Introduction Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are very common worldwide both in the developing and developed regions. Many STI patients can present with modified, atypical, minimal or even absent symptoms or signs. Hence STIs are considered a silent epidemic, they are difficult to eradicate though we increasingly know more about them. The silent nature of the sexually transmitted disease (STD) epidemic is perhaps its greatest public health threat. People continue to underestimate their risk because they have minimal symptoms or are asymptomatic. The exact extent of STD in the world is unknown. The best estimate came from the World Health Organisation (WHO) study in 1995 that at least one million new cases of STIs occur daily in the world.1 Since then, WHO has recommended the syndromic approach to diagnosis and management of patients with STIs and this has been implemented in many developing regions hoping to avoid the cost of testing and to provide expedited care. Treatment at the first visit has the limitation of not addressing the issue of subclinical and asymptomatic STIs.2 However, this approach has proven to be effective in contributing to control of STIs including sexual transmission of Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.3 The mutually reinforcing nature of HIV and STIs has been termed "epidemiological synergy". Numerous studies have indicated at least a threefold to fivefold increased risk for HIV infection among persons who have other STDs including genital ulcer diseases and non-ulcerative, inflammatory STDs.4 Even with the availability and access to the best effective treatment modalities for STI, primary prevention of STIs is always considered more essential, cost-effective and efficient. Secondary prevention requires practitioners to have good clinical skills in order to recognise the STIs and to give treatment early. The clinical presentations of the following common STIs in Hong Kong, namely Gonorrhoea (GC), Non-specific genital infection/Non-gonococcal urethritis (NSGI/NGU), Genital wart (GW), Genital herpes (GH) and Syphilis will be briefly reviewed and their treatments updated. Principle of management of STIs The following mnemonic is always useful as reminder of the principles of management of STIs. ABC in management of STIs:

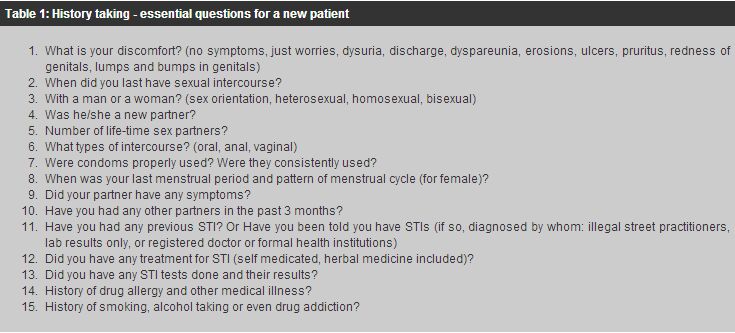

This mnemonic is easy and simple to remember but how to transform it into good and persuasive advice to our patients is another skill and challenge. One very common question asked by our clients is "Are condoms effective against STIs?" The answer is, "Yes, if used consistently and correctly". Male condoms are highly efficacious offering protection against HIV infection, gonorrhoea and unintended pregnancy though we must be aware that the infectivity of different STIs varies and that the slippage and breakage rate of condoms can account for failure of condoms to prevent STIs.5 Most HIV/STI transmission occurs because of condom non-use or inconsistent use. A good physician will commence management by discussing the choice of management from patient's point of view. The advice should not be dogmatic and reproaching but should be more tactful, considerate and caring. As observant and caring doctors, we must appreciate that most of the patients with STIs when stepping into the consultation room seeking advice or treatment of STIs are in a state of anxiety and apprehension, with the risk of subsequent misinterpretation and wrong perception of the doctor's advice if that is not properly handled. Controversy and misunderstanding may arise if the attending doctor is not aware of this. As clinicians, we must invest more time to communicate with our patients and to get and gain their rapport. This is essential for successful management especially when we are dealing with some incurable viral STIs, family problems, partner relationship and contact tracing. Furthermore, it is not uncommon to see patients who have been shopping around between numerous practitioners (registered or non-registered) handing in a pile of laboratory results requesting our comments. The tests may be helpful but they sometimes can be detrimental if not interpreted properly. Investigations and laboratory findings alone can never replace a consultation process in good hands. It is essential for pre-test counselling for some tests such as HIV testing thereby avoiding the emotional crisis of unexpected results. History taking and physical examination It is important for a good clinician to take a non-judgmental sexual history, a detailed travel history and a medication history, before doing an examination of the genitals and general examination. In the presence of limited resources for both patients and health providers, history taking is the most valuable tool for the clinician and offers the best approach to patients with STIs. A good family doctor has the advantage of knowing better and in more depth about the patient's character (e.g. a hypochondriatic or not), the family bonds and background so that more holistic care can be delivered. Management of STIs by the family doctor is not uncommon according to one survey by Social Hygiene Service.6 WHO recommends integration of prevention of STIs into primary care. I cannot overemphasise the importance of careful history-taking supplemented by a meticulous physical examination. A non-judgmental view from the clinician is essential. Unfortunately there are still some health care workers who are reluctant or refuse to manage clients with STI problems due to personal bias. Of course regular updates of professional knowledge on the management of STIs are important to ensure the best quality management is delivered to our clients. Clinical examination is best conducted in privacy and in the presence of an experienced chaperone. Adequate explanation of the procedure to patients prior to the examination can ease and better prepare the anxious patient. A good source of lighting for examination, and personal protective gear including gloves, goggles, gown and face mask are best available for both specimen collection and examination. A quick general examination should be done before proceeding to the genital examination. Males can be examined standing or lying flat on an examination couch with trousers and underpants lowered to beneath knees. The inspection and palpation of pubic hair, external genitals, regional lymph nodes, scrotum, testes, penis, retraction of prepuce to expose glans penis and urethral meatus, perianal region with or without rectal examination should be properly conducted. Examination of the female is more complicated and will be like that of a gynaecological examination. The patient should be examined in an examination room in lithotomy position on a gynaecological table. Apart from superficial examination like that in a male patient, speculum examination with disposable speculum (with or without Pap. smear) and bimanual pelvic examination are usually conducted for complete female genital examination.

Routine investigations and specific treatment In general, blood tests for HIV antibody7 and syphilis serology are needed for anyone who has been involved in high risk behaviour because both HIV infection and syphilis can often be asymptomatic and only be confirmed by blood tests. Other investigations are mainly microbiological tests that will depend on the availability of such service and the presence of abnormal signs such as discharge or ulcers. The best practical approach can be guided by the pamphlets first distributed by Department of Health on STD case management in 1998 and later updated in 2002. More detailed treatment guidelines can be found in the appendices of the Handbook of Dermatology and Venereology 3rd edition. Syphilis

STDs are not notifiable communicable diseases in Hong Kong and often their local

trends can only be inferred from data from public STD clinics. The number of new

cases of syphilis recorded in public STD clinics of Hong Kong in the year 2002 was

1061 (15.63 cases per

There may be a wide range of skin manifestations and a more atypical presentation if the sufferer is also HIV positive. The primary stage of syphilis may consist of multiple or more extensive chancres in a HIV positive patient. HIV positive patients may more likely and more rapidly progress to neurosyphilis within first two years of diagnosis.8 It is also important to note that a biological false positive VDRL test is more commonly found in the HIV positive patient and hence specific serological tests for syphilis must be done (Treponema pallidum haemagglutination test (TPHA) and Fluorescent treponema pallidum absorption antibody (FTA) test) for confirmation. Rarely, when serologic tests are inconsistent with clinical suspicion in HIV positive patients, skin biopsy of the skin rash or lesions will help to clarify the picture: most of the time, these cases require referral to specialist for further evaluation. The most effective treatment for syphilis in HIV negative or HIV positive patients is still penicillin, ever since it was put into clinical use in 1943: daily intramuscular injection of procaine penicillin G (PPG) in an outpatient setting. The dose prescribed for adult varies according to the stage of syphilis. The early stage syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent) requires 1.2 megaunits of PPG imi daily for 10 doses. The late stage syphilis (late latent, tertiary syphilis) requires longer course (up to 3 weeks) with higher dose (2.4 megaunits of PPG) with concomitant use of oral Probenecid 500mg qid to maintain a high serum penicillin level. Team management involving other specialists e.g. cardiovascular physicians, neurologists, ophthalmologist, geriatricians and psychiatrists will offer the best outcome for the patient with late syphilis. Other alternative antibiotic treatments (like ceftriaxone, tetracycline, azithromycin) are also effective but less well documented and studied for prevention of neurosyphilis and congenital syphilis in pregnancy. In case of allergy to penicillin when the patient is left with no other choice such as pregnancy, admission to hospital for close observation for a desensitisation programme can ensure delivery of a safe and effective penicillin treatment regime.9 Gonorrhoea and non-gonococcal urethritis/non-specific genital infection

The number of Gonorrhoea and NGU/NSGI new cases recorded in public STI clinics of

Hong Kong in the year 2002 was 3287 (48.43 cases per

Genital herpes

The number of genital herpes new cases recorded in public STI clinics of Hong Kong

in the year 2002 was 1432 (21.1 cases per

Non-specific immunoassays (Enzyme Immunoassays) for HSV antibody have been commercially available and used by many private laboratories for many years. These tests using crude antigen of HSV while useful in detecting HSV antibodies are unable to distinguish between the HSV type 1 and type 2 as there is extensive cross-reactivity between HSV-1 and HSV-2. These tests offer very little help to clinicians. One should never diagnose a patient with genital herpes based on the result of such immunoassays. Western blot assay is considered the gold standard for the detection of type-specific antibodies to HSV. It is accurate in detecting type-specific antibody responses but it is expensive and is usually only available in large research laboratories. Glycoprotein G-based type-specific serologic assays are the newest development in helping herpes diagnosis. These tests offer a quick and often accurate diagnosis of HSV, and have the added advantage of distinguishing between HSV-1 and HSV-2. Type-specific antibody tests detect antibodies to glycoprotein G (Gg), an outer envelope glycoprotein that is structurally different between HSV-1 and HSV-2. These tests are now commercially available in the market in US. Clinicians must check with their laboratory if they are using one of these tests. Even equipped with these useful tests, counselling offered by the clinician is of utmost importance for an accurate diagnosis of genital herpes.15 Informing the patient that he or she is having an attack of genital herpes (with clinical lesions found), or has had an attack and is harbouring the infection (may never note the lesions) may be a very delicate matter. A clinician must be fully prepared for counselling before ordering type specific serological tests for herpes simplex virus. We have to realise the impact on the patient of revealing the test results and to be aware of its useful clinical application. The test will be extremely useful to confirm the diagnosis of some recurrent atypical symptoms, discordance on clinical presentations (when one partner with clinical and culture confirmed diagnosis of genital herpes has a partner who is totally asymptomatic) and the management for pregnant women when the sex partner is known to be suffering from genital herpes. Frequently recurrent genital herpes can then be accurately diagnosed by the use of the type specific test and the specific antiviral treatment will offer relief for this category of patients (previously they could be misdiagnosed and treated as having persistent chronic NGU/NSGI). If the sex partner of a pregnant woman is diagnosed with genital herpes, then serological tests will help establish whether or not the pregnant mother is susceptible to a primary attack of genital herpes during the pregnancy, and will affect the subsequent plan of management of pregnancy by her obstetrician. However, discordance of the type specific serology tests for herpes simplex virus between sex partners should be handled tactfully to avoid relationship or infidelity problems. In summary, the clinician must check with the laboratory whether or not it is using a truly type specific HSV antibody test. He or she must be familiar with the given test before ordering it, be able to interpret its result and to determine how helpful it will be to the current management. The treatment for active episodes of genital herpes is mainly symptomatic and suppressive. It is generally recommended that specific anti-viral therapy is beneficial when it is initiated early - within 24 hours of lesion onset or during the prodrome that precedes some outbreaks. Oral Acyclovir 200mg five times daily for five days has the longest clinical safety record and is effective for treatment of genital herpes. Newer anti-viral medications have similar efficacy and have an advantage of less frequent dosing, e.g. valacyclovir 500mg twice daily for five days or famciclovir 125mg twice a day for five days. Genital wart

The number of genital wart new cases recorded in public STI clinics of Hong Kong

in the year 2002 was 3245 (47.81 cases per

There is evidence to confirm the effectiveness of the male condom in reducing the risk of acquiring genital wart.17 Other risk factors include the number of lifetime sexual partners, and smoking tobacco. On the whole the management of genital wart depends very much on the individual's immune response to the HPV infection, clinicians should explain clearly the risks and complications of the condition. After clinical remission, advice on prevention of acquiring genital wart in the future should be given to the patient as there are many genotypes of genital wart and re-infection with a new type is possible. The treatment of genital wart can be divided into surgical or medical methods. Before implementation of any treatment modality, the attending physician should make sure that the client understands the nature of genital wart and the choice of treatment. There is no cure of the infection but removal of clinical lesions can be achieved by either surgery or medication. Surgery is operator or health-care worker dependent. Surgical methods include simple surgical excision of the genital wart, carbon dioxide laser vaporization, electromagnetic loop electrosurgical excision, electrodesiccation and cryosurgery. Medications can either be applied by patients themselves or by physicians. Medications that required application by health workers or providers include intralesional or systemic interferon alpha injection, intralesional Bleomycin injection, topical application of 25% podophyllin resin, topical application of trichloroacetic acid. The newer topical applications are more convenient and user-friendly because patients can apply them to themselves at home e.g. 0.5% podophyllotoxin solution or cream (Cytodestructive chemicals), 5% imiquimod cream (Immunoenhancing chemical), 5% 5-fluorouracil cream (Cytodestructive chemicals), and 1-5% cidofovir gel (Viricidal - still experimental). A review and analysis of the direct medical costs for both surgical and medical treatment of genital wart has concluded that surgical modalities and podophyllotoxin are relatively low cost options.18 However, the choice of treatment will depend very much on the clinical types of genital wart, patient's personal perception of "control or cure of the condition", patient's level of tolerance of resulting scarring and pain, as well as the practical availability of treatment options in particular health-care settings. A thorough and detailed explanation of the procedures is essential to alleviate any misunderstanding and dispute, and is a must for good clinical management. Conclusion All family doctors should have some knowledge of the clinical management of common STIs as these problems are not uncommon in Hong Kong. A good family doctor may actually be in a better position to give advice to patient and his/her sex partners during management on the social and family issues resulting from STI. The ABC concept of prevention of STIs can be effectively delivered to our patients during the treatment period and these should not be left out in the management. The serological tests for screening of syphilis and HIV infection are to be included for all those who have conducted high-risk sexual behaviour. Gonorrhoea and NGU/NSGI are common and they are amenable to cure by antibiotic treatment though we need to monitor for resistance and treatment failure. There have been some advances made in the management of viral STI both in investigations and their treatments. Continual update on these will help us to be better equipped to manage difficult STIs though not all of them can be readily eradicated. Key messages

Further reading

K K Lo, FRCP, FHKCP, FHKAM(Medicine)

Consultant Dermatologist-in-Charge, Social Hygiene Service, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Dr K K Lo, Social Hygiene Service, Department of Health, 3/F, West Kowloon Health Centre, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

References

|

|