|

May 2005, Volume 27, No. 5

|

Update Articles

|

Basic communicating and counselling skills for family physiciansDavid Y F Ho 何友暉, Orchid H L Wang 汪惠蘭, Siu-Man Ng 吳兆文, Rainbow T H Ho 何天虹 HK Pract 2005;27:180-190 Summary Family physicians often encounter psychological problems in patients under their care. Treating these problems is integral to a holistic conception of primary healthcare. This article describes the nature, basic principles, and therapeutic process of counselling; dispels myths, biased perceptions, and misconceptions about it; and illustrates how counselling techniques may be applied by family physicians in their practice. The authors make a proposal to confront limitations and contradictions of treating psychological problems in primary healthcare: setting up synergistic partnerships between family physicians and health counsellors. 摘要 家庭醫師常常發現在他們照顧的病人當中,有不少心理問題。對基層醫療保健的整體構思而言, 處理這些問題是必須的。這篇文章描述輔導的本質、基本原理與治療程序;消除有關對輔導的神話、 偏見與誤解;並闡明家庭醫師怎樣可以在他們的醫務中應用溝通與輔導技巧。 作者針對在基層醫療保健中處理心理問題時遇到的局限與困惑,提出一個建議: 家庭醫師和健康輔導員之間建立互補、互相促進的夥伴關係。 Introduction As front-line practitioners, family physicians occupy a strategic position in the system of healthcare delivery. Many patients under their care have psychological problems which, though not necessarily serious enough to be considered as disorders, require attention because they may exacerbate existing medical conditions (e.g., psychophysiological or psychosomatic disorders). These problems, if prolonged, may undermine the psychoneuroimmunological system and thus render the patients more vulnerable to disease. This is not to mention the suffering they in themselves cause to the patients and their families. Thus, if unrecognized or untreated, psychological problems remain a negative factor in the patients' health (conceived holistically) and hence their quality of life. However, family physicians often do not attend to psychological problems. The reasons are many. Some simply exclude, by definition, psychological problems from their domain of responsibility: "Psychological problems are not medical problems with which we are charged to deal." Some find it convenient to ignore them: "Why bring upon ourselves messy problems needlessly?" Dealing with psychological problems is time consuming and hence not cost effective. Furthermore, compliance is difficult to achieve and outcomes are uncertain and intangible. Some, more conscientious, acknowledge their responsibility, but feel handicapped by a lack of requisite skills to treat, let alone recognize, psychological problems. From the perspective of community psychiatry, primary care physicians are in the best position to identify and help people with common mental disorders.1,2 According to a WHO multinational study,3 the overall prevalence of mental disorders with well-defined criteria among patients in primary care is 24%. The figure is the lowest for Shanghai (7.3%), and the second lowest for Nagasaki (9.4%). The most common diagnoses are depression, generalized anxiety disorder, neurasthenia, and problems with alcohol. However, psychological problems constitute only 5.3% of patients' presenting complaints. The figure is the lowest for Shanghai (0.2%), and the second lowest for Nagasaki (1.3%). Primary care physicians recognize 48.9% of mentally disordered patients as having a psychological disorder. Shanghai has the lowest rate of recognition (15.9%), and Nagasaki the third lowest rate (18.3%). Taken together, the WHO data illustrate that the recognition of psychological disorders and symptoms presents a formidable challenge to family physicians - particularly in Confucian-heritage cultures, such as China and Japan. It is thus fitting to remind ourselves that psychoanalysis, the ancestor of modern psychotherapies, began with the treatment of neurotic patients in general practice more than a century ago. In this article, we argue that, as primary-care givers, family physicians can ill afford to ignore psychological problems, the treatment of which is integral to an adequate conception of sickness and health. Armed with even basic counselling skills, family physicians can go a long way to alleviate and, more importantly, prevent psychological problems from working out their harmful effects. A common example serves to drive home this point. A woman underwent a caesarean operation and, subsequently, suffered from dyspareunia for years afterwards. This example illustrates several therapeutic principles. Surgical operations often have psychological sequelae that escape the physician's attention. If untreated, such sequelae may lead to problems that become more extensive, involving not only the patients but also their families. Sensitive topics, such as those involving sex, may be embarrassing to discuss by not only patients but also physicians. A physician may apply counselling skills to confront the psychological sequelae, and alleviate the patient's fear of pain in general and dyspareunia in particular. Psychological problems are a part of life. In themselves, they do not determine one's health status; but failure to confront them will surely undermine it. The ideal is that family physicians can identify and handle the majority of cases, with communication and counselling skills incorporated into their practice. Only the more difficult or entrenched cases need to be referred for longer term treatment. In what follows, we characterize the nature of counselling, and illustrate how basic counselling principles and skills may be applied judiciously by family physicians to enhance the efficacy of their practice. The nature of counselling The schools of thought in counselling are many. We refer interested readers to some relevant texts.4,5 Here, we recast counselling as helping clients to learn to take actions for solving problems of living and grow psychologically, in accordance with Dialogic Action Therapy (DAT).6 DAT integrates two cardinal ideas, dialogics and action, both of which are quintessential to defining what it means to be human. The first idea reflects the fact that most therapeutic systems entail not only dialogues between two persons, the therapist and the client, but also internal dialogues (self-talk) within either or both of them. Internal dialogue takes varied forms: imaginary dialogues between one's different selves (e.g., the actual and rejected, the present and the future), between oneself and others, between oneself and one's deceased significant other, and so forth. In DAT, the counsellor exploits these dialogues to achieve therapeutic gain. The second idea stresses that action is essential to the therapeutic process. It demands taking effective corrective actions as an outcome indicator. It accords with the time-honoured saying, "Action speaks louder than words." Taking effective action entails learning from experience. It does not mean doing something aimlessly or compulsively. Sometimes, it may take the form of active inaction - more precisely, letting go. This applies especially to cases where nonproblems become problems as a result of compulsivity, unrealistic expectations, and the like. A typical example is problems arising from parents' excessive worries over their children's academic performance. In short, DAT is dialogical, action oriented, and solution focused. It embraces a conception of the dialogic self that has immense potential for creative self-transformation.7 In line with prevailing thinking in behavioural health, it stresses the need for assuming responsibility for one's own health through taking action. Psychotherapy, counselling, and guidance lie on a continuum of helping. They differ primarily with respect to the target population and goals of intervention. Typically, psychotherapy refers to the treatment of clients who have psychiatric or psychological disorders, or whose problems are serious enough to require intervention. The aim of counselling is to facilitate problem solving and psychological growth among "normal" persons, whose problems, if left untreated, may result in varying degrees of social, familial, or occupational maladjustment. (By "normal," we mean meeting the requirements of living adequately, though not necessarily optimally. A normal person is not the same as a healthy person.) Guidance refers to explicit, judicious use of information, advice giving, and education for normal populations. Prevailing opinion places counselling somewhere between psychotherapy and guidance. The boundaries are not sharply defined; the terms psychotherapy and counselling, in particular, are often used interchangeably. Counselling differs from traditional medical treatment in some basic respects. First, it stresses working with clients, rather than doing something to them. Accordingly, it places the responsibility for healing and getting well ultimately on the clients themselves. The counsellor facilitates the healing process by activating their inner, dormant resources to solve their own problems. Viewed in this light, all healing is self-healing. Second, counselling does not presuppose an underlying psychopathology located within individual clients responsible for their troubles; rather, it locates problems of living in their societal and cultural contexts, not only within but also between persons. Third, counselling seems easy to learn; but, in reality, it is extremely difficult to master. It cannot be reduced to a set of procedures, as in a cookbook, to follow. To use an analogy, it is not enough to provide counselling road maps to students - contrary to the impression that many teachers and counselling texts convey. Students have to learn to construct cognitive road maps by themselves. That is because dilemmas, uncertainties, and ambiguities are inherent in counselling. Each case renews the challenge to counselling judgment and creativity, something that may be fostered, but impossible to teach. Ultimately, the therapeutic instrument is not a needle or a knife, but is embodied in the counsellor's humanity. Unfortunately, the cookbook approach to counselling, replete with do's and don'ts, is all too common. A typical prescription for professional conduct is: "Counsellors should be warm and accepting of clients." But can feelings and attitudes be prescribed? If yes, how can they be genuine? Warmth and acceptance may be cultivated, not prescribed; they come naturally when people embrace life, and receive them as a way of life. Myths, biased perceptions, and misconceptions Myths, biased perceptions, and misconceptions about counselling, for which the counselling profession itself cannot escape responsibility, have bedeviled practitioners and hampered its acceptance by the medical profession. Among these are the following. (i) All counselling is "one-to-one talking cure" Two tacit tenets underlie psychoanalysis and, subsequently, different schools of thought derived from it. The first is that psychotherapy is a one-to-one affair, between the doctor and the patient. The second depicts psychotherapy as "talking cure." To be unconstrained by these tenets lies the future of psychotherapy and counselling. Therapeutic groups would then become the treatment of choice whenever feasible, over treating patients individually, for both their cost effectiveness and amplification of therapeutic effects. Practitioners would then appreciate the primacy of actions over spoken words. (ii) Counsellors have to maintain professional distance and emotional detachment True, counsellors are ethically required to keep professional boundaries (e.g., avoid getting emotionally involved with their clients). Unfortunately, many misinterpret this admonition as avoiding emotional reactions to their clients, or even rationalise their lack of concern for clients as "emotional detachment." But emotional reactions are natural, especially in counselling. How can we ask counsellors to be less than human? Informed by the cultural metaphor, "The healer has the heart of a parent," Chinese clients expect sympathetic concern, emotional support, and active involvement from a parent-like figure. They may thus perceive the emotionally detached counsellor as aloof and uncaring. Reading one's own emotional reactions to another person accurately is both informative and necessary: informative, because it helps one to be more aware of self-other interaction at the emotional level; necessary, because appropriate responding depends on accurate reading. Skillful counsellors harness their emotional reactions, both positive and negative, to serve therapeutic purposes. (iii) Counsellors do not form value judgments of clients Counsellors who come across as judgmental to their clients are inept. However, being nonjudgmental is not the same as being value free. People can no more avoid value judgments than they can negate their moral being and, indeed, their human nature. Being cognizant of one's values serves to guard against imposing them on others and, more fundamentally, monitor one's ethical conduct. Similarly, counsellors should be impartial in dealing with interpersonal conflicts; but impartiality does not mean neutrality. How can they be neutral when dealing with cases of child abuse, for instance? (iv) Counsellors are nondirective; they are nice people who have to accept their clients unconditionally Doctrinaire followers of Carl Rogers, the founder of person-centred counselling, are to blame for this biased perception. By virtue of their professed intention to help others, counsellors have to bring to the client's attention problems he has avoided or failed to resolve. This arduous, unpleasant task is likely to arouse discomfort, even pain, in the client - the exact opposite of being "nice." In large measure, "nondirectiveness" has become a synonym (i.e., excuse) for passivity or, worse, wish-wash ineffectiveness. Directiveness does not mean being domineering or telling clients what to do. Rather, it means providing a general direction and delineating a framework within which the client works in collaboration with the counsellor toward problem solving and psychological growth. In point of fact, it is impossible to avoid directiveness totally: The counselling context itself is one in which the counsellor is expected to exercise therapeutic influence over the client and is, to this extent, inherently directive. How directive or nondirective a counsellor should be depends on the differing therapeutic requirements of the moment in each case. A counsellor may have to be somewhat directive, even authoritative (not authoritarian!), in the beginning, and be less directive as counselling progresses. The goal is to facilitate the development of self-direction. Unconditional positive regard and acceptance is a myth that has bedeviled counsellors, obliging many to become inauthentic and play a phony role. It is difficult to savor how anyone could, or should, show unconditional positive regard to the likes of Adolph Hitler or Saddam Hussein. In real life, unconditional acceptance probably exists only in parents toward their young children. (Arguably, dogs are more likely than humans to display unconditional acceptance toward humans.) That there are so many unhappy people requiring counselling speaks to the possibility, even likelihood, that unconditional rejection is a more common experience than unconditional acceptance. Rogerians may defend themselves by saying that unconditional acceptance applies to the person, not to the person's actions. They immediately face, however, an objection to their defense. A person's essence is defined by his actions. A person who acts despicably is a despicable person; the same person is no longer despicable when he ceases to act despicably. There is no way to escape from the conditional nature of acceptance without incurring the hazard of abandoning irreducible ethical standards. In sum, we object to the notion of unconditional acceptance, because it is not only unrealistic but also indefensible on ethical grounds. To avoid being misunderstood, we hasten to add that none of what we have stated negates the core values of compassion and the intrinsic worth of all human life.Conditional acceptance does not imply rejection, conditional or unconditional; it does not negate caring for the client as a person. Most important, in accordance with DAT, we affirm our conviction in and respect for the human capacity for self-transformation, without which counselling would be a hopeless task. This conviction and respect translate into a potent therapeutic force to facilitate change - even in persons who deserve little or no positive regard. (v) Counselling is primarily a matter of giving proper advice to clients This misconception is as unsound as its opposite extreme, blanket nondirectiveness. Although it is part of the counsellor's work, giving advice is advisable only when the patient is ready to take the advice seriously. Readiness requires time and effort to achieve. In other words, timing is critical. Giving advice prematurely or indiscriminately can be not only futile, but also countertherapeutic. After all, the patient has probably heard the advice given innumerable times before - to no avail. Furthermore, a higher goal, which demands greater skill, is to enable the patient to come up with sound advice by and for himself. (vi) Counselling is the answer to human suffering This popular misconception underlies counselling's mass appeal. Unfortunately, it is also symptomatic of the naive, romanticized views many have toward counselling. In truth, counselling provides no answer to catastrophic suffering caused by war, ethnic cleansing, economic exploitation, ecological disaster, and so forth. Neither can it provide an answer to the many misfortunes of ordinary life, such as unemployment and having an unhappy marriage. Counselling promises to help only when there are identifiable responsibilities on the part of the client or his significant others, which, when assumed, will make a difference in his life. For instance, the hope for change begins with the realization that one may be responsible, at least in part, for one's unhappy marriage. The responsibilities to be assumed include how one responds to and perhaps thrive in the face of adversity - even to misfortunes outside of one's control (e.g., an accident resulting in serious injuries), or problems not of one's own making (e.g., marital difficulties arising from an arranged marriage to an abusive person). Delineating the battleground for assuming responsibility and taking corrective action, therefore, is central to counselling. Helping people to assume responsibility for their own lives is no mean achievement: It may signify a battle already half won. The irony, however, is that all too often those who need to assume responsibility the most are also the least likely to do so. In other words, people who need counselling the most are also the least likely to be receptive or responsive to it. Countless people do foolish things (e.g., engage in addictive gambling, shopping, or surfing the Internet) on a daily basis to destroy lives, their own as well as those close to them. Yet, the idea of counselling probably never occurs to them. This reality speaks to self-destructiveness as a constant part of the human condition. It contradicts the article of faith many counsellors (especially those of the person-centred persuasion) hold dear: "All persons have the propensity for self-actualization." (vii) A summation This section is not meant to discourage anyone. Rather, it follows the dictum that truth, however painful, is better than falsehood. Counselling is replete with contradictions. In case after case, what needs to be done may be clear from the beginning; yet, clients stubbornly refuse to act in their best interests - just as, in medicine, there is no lack of patients who fail to comply with medical advice to save their lives. Frustration tolerance, humility, and courage to confront contradictions, therefore, are requirements of being a counsellor. When and only when counsellors are awakened to romanticized falsehoods, on which many have long based their practice, will they be more empowered to make a difference in their clients' lives. Therapeutic process It is impossible, and inadvisable, to predetermine the therapeutic agenda at the beginning of treatment. In the course of treatment, new problems may be uncovered, old problems thought to be solved may resurface, and unforeseen circumstances beyond the control of the physician or the patient may appear. Thus, in counselling, diagnosis and treatment are not separable, with the former neatly preceding the latter. Nevertheless, we may sketch a general outline of the therapeutic process.

1. Give top priority to the formation of a trusting, or at least a working, relationship

between the physician and the patient. Listen and observe first; give advice later.

Communicating, relating, and interviewing Communicating, relating, and interviewing skills are fundamental to counselling (and, more generally, interpersonal interaction). The following is a distillate of some general principles. 1. Values and attitudes are fundamental and more important than skills Truthfulness (真實), sincerity (真誠), emotional honesty (真情), and authenticity (真摰) are probably the most fundamental values of counselling. Playing the role of an accepting counsellor without any of these values would not come across well; patients can easily detect its phony quality. Counselling entails, therefore, much more than the mere acquisition of skills. Genuine acceptance means much more than having good "bedside manners." It is based on a deep respect of the humanity of each patient. However, acceptance does not mean agreement. We may, and should, rectify patients' unfounded, erroneous, or superstitious beliefs concerning illness or health. 2. Attentiveness and active listening hold the secret to effective clinical interviews An interview is not an interrogation. The ideal interview is one in which the physician obtains essential information from the patient, without having to ask too many questions. This may be achieved when rapport is established and the patient senses that the physician is trustworthy, nonjudgmental, and interested in what he has to say. 3. Use language that is common to the physician and the patient

Counselling disavows the use of language used in academic discourse (e.g., jargons).

Technical terms should be explained carefully. (Diagnostic labels such as schizophrenia,

brain damage, and the like are particularly scary.) Here is an example of a horrible

explanation: 4. Patients must also understand therapeutic principles

Therapeutic principles have to be translated conceptually and linguistically into

a language familiar to the patient, drawing upon indigenous concepts congenial to

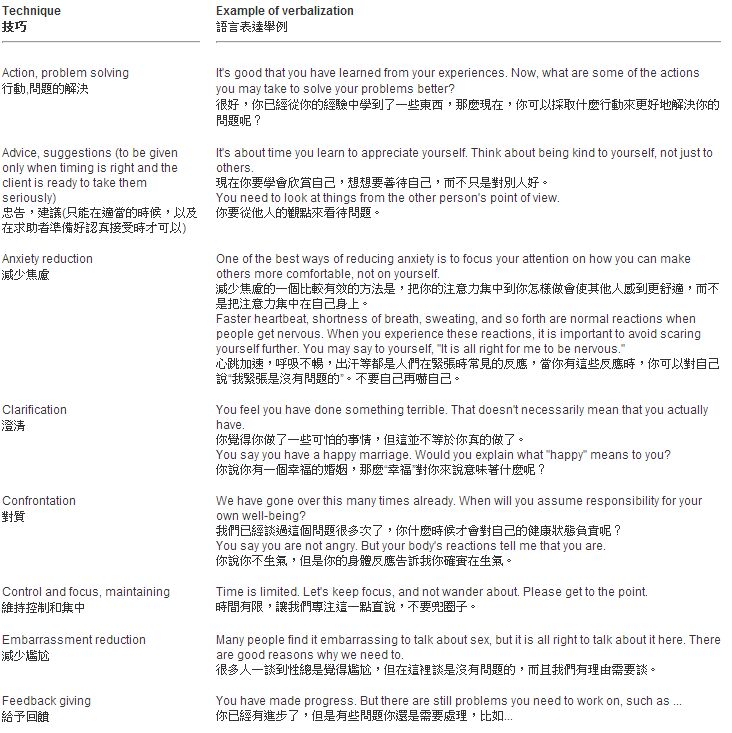

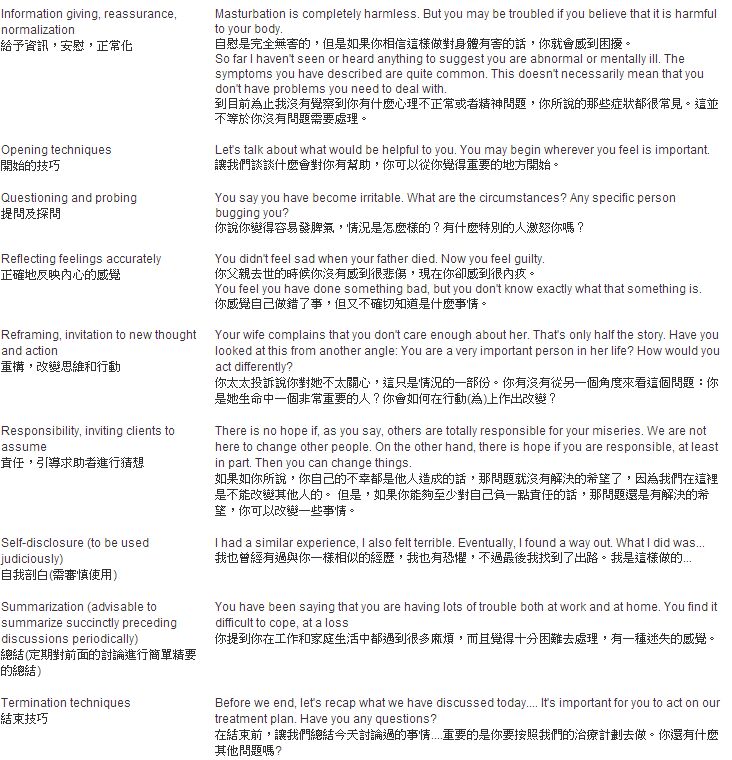

those principles. The following are some examples. 5. Use open-ended questions In general, it is better to use neutral, open-ended questions first and, if needed, follow up with multiple-choice or yes-no type of questions for clarification. A question like "do you have trouble at work?" tends to evoke a "yes" or "no" response. "What is your situation at work like?" invites informative responding. 6. Keep verbalizations short and to the point This will make it easier for patients to comprehend and remember what the physician wants to convey. Interview and counselling techniques The following presents an illustration of specific skills commonly used in interviewing and counselling, in the light of the foregoing principles.and remember what the physician wants to convey.

Conclusion: A timely proposal Clearly, counselling holds great promise for family physicians to relate more comfortably with patients and members of their family, and thus intervene more effectively in their clinic. However, applying basic counselling skills in their practice is fraught with limitations and difficulties. Hong Kong society is in dire need to foster a culture of interprofessional respect and cooperation; more generally, to develop a comprehensive and cost-effective primary healthcare system. The strategic use of limited professional time and resources in such a system is a major consideration. In keeping with our own advice about not to give advice until timing is right, we have delayed the impulse to put forward the following proposal until now: Set up synergistic partnerships between family physicians and health counsellors (whose specialty is health promotion and education). These partnerships require a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities. For instance, a health counsellor, working in close consultation with the family physician, may perform many of the counselling, liaison, and referral tasks we have described. To avoid fragmentation of service and inconvenience to patients, it is preferable for the family physician(s) and the health counsellor(s) to be located in the same setting. Making a proposal for marriage may be premature. However, initiating courtship is both timely and exciting. It promises to overcome limitations and difficulties of applying counselling in family medicine, an essential step toward establishing primary healthcare in Hong Kong as among the advanced in the world. Key messages

David Y F Ho, PhD

Senior Consultant, Orchid H L Wang, BSN Honorary Clinical Associate, Siu-Man Ng, BHSc, RCMP, MSc, RSW Assistant Professor, Rainbow T H Ho, PhD Research Officer, Centre on Behavioral Health, University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Professor David Y F Ho, Centre on Behavioral Health, 10 Sassoon Road, Hong Kong.

References

|

|