Summary

Most glaucoma patients have no symptoms and quite

often their disease are only suspected or confirmed during routine eye

screening. It is a slowly progressive condition in which the retinal

nerve fibers degenerate. If untreated, blindness is almost invariable

although the time course and speed vary. Up to the current moment, intraocular

pressure reduction is the only effective mechanism of treatment by which

the disease process can be slowed or stopped. The role of neuro-protection

medications is still uncertain.

摘要

大多數的青光眼病人沒有任何症狀,通常是眼科常規檢查時被懷疑或確診患有該病。青光眼是視網膜神經慢性的進行纖維退變。若未經治療,就會導致失明,雖然病程和失明的速度有所不同。到目前為止,降低眼壓(IOP

reduction)是唯一可減緩或終止疾病過程的有效機制。神經保護藥物的作用尚不清楚。

Introduction

Glaucoma is a heterogeneous group of ocular diseases

that manifest as a progressive optic neuropathy and visual loss.1,2

Visual field loss and even irreversible blindness occur if glaucoma

is not appropriately diagnosed and treated. Despite the availability of

intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering agents that may arrest or slow disease

progression, glaucomatous blindness still occurs.

Acute angle-closing glaucoma can be considered to be a separate

entity in which patients may not have any visual field defects or high

IOP before the attack. It happens in individuals who have occludable angles

as a result of naturally-occurring or acquired abnormal anatomy of the

angle structures. During the acute attack, patients have symptoms of severe

ocular pain and headache, blurring of vision and nausea and vomiting as

a result of rapidly increasing IOP. Even with effective medical and laser

treatment, some of these acute cases may eventually end up in some forms

of chronic angle- closure glaucomas, the consequences of which may be

similar to those of the chronic open-angle types. The main focus of this

paper concentrates on the various clinical aspects of the latter.

The nature and burden of

glaucoma

Most glaucomas are insidious in nature, with no symptoms

or warning signs prior to advanced visual field loss.1,2 At

least half of the patients with open-angle glaucoma are not receiving

treatment because the disease is undiagnosed.1,3-6 Among treated

glaucoma patients, poor compliance is a major obstacle.2,7,8

It is estimated that 6.7% of the 67 million people with glaucoma worldwide5

- and 120,000 of the 3 million people afflicted with it in the United

States1 - are blind as a result.

Glaucoma is a significant public health problem. In

the United States alone, glaucomatous blindness costs an estimated US$1.5

billion annually in Social Security benefits, lost income tax revenues,

and healthcare expenditures.9 Added to the economic burden

imposed by blindness is the impact on patients' lives. Even before blindness

occurs, patients diagnosed with and treated for glaucoma may be troubled

by treatment inconvenience and the fear of vision loss.

Epidemiology of glaucoma

Glaucomatous optic neuropathy is most prevalent among

people of African origin, and least prevalent in full-blooded Australian

aborigines;10 Asian populations have rates intermediate between

theses two groups. European- and African- derived peoples suffer predominantly

from primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), whereas rates of primary angle-closure

glaucoma (PACG) are higher among East Asians than in other populations.

Glaucoma as a cause of blindness

Population surveys in Mongolia found glaucoma to be

the cause of 35% of blindness in adults (cataract being the cause of 36%

of blindness).11 Among Chinese Singaporeans, 60% of adult blindness

was caused by glaucoma.12 Cautious extrapolation of these data

suggests that around 1.7 million people in China suffer blindness caused

by glaucoma. PACG is responsible for the vast majority (91%) of these

cases.13 Secondary glaucoma is the most common cause of uniocular

blindness.

Glaucoma is the leading cause of registered, permanent

blindness in Hong Kong (23%).14 In Japan, diabetic retinopathy

(18%), cataract (16%) and glaucoma (15%) are the leading causes of blindness.15

Risk factors for glaucoma

Apart from high IOP's, advancing age is the single most

consistent risk factor for all types of glaucoma.12,16-23 A

positive family history is also a risk factor for glaucoma.24,25

Female gender is recognized as a major predisposing factor toward the

development of PACG.12,20,23 There is little clear evidence

to support a gender difference in POAG. Those of Chinese ethnic origin

are at a higher risk of developing angle-closure glaucoma than those of

Malay descent and South Indian people.16,17 All the above

and in particular raised IOP have been shown by Foster et al in

a recent Singaporean Study to be risk factors for glaucomatous optic neuropathy

in Chinese people.26

A shallow anterior chamber has long been recognized

to be a factor that predisposes toward angle-closure.27 The

depth of the anterior chamber reduces with age and tends to be shallower

in women than in men.28,29 There may also be an association

between myopia and POAG.30 Other risk factors are diabetes

mellitus, hypertension and a thin central corneal thickness (<0.5mm).

Intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression

As mentioned above, glaucoma does not refer to a single

disease entity, but rather to a group of diseases that have certain common

features, including high IOP (too high for the continued health of the

eye), cupping and atrophy of the optic nerve head, and visual field loss.

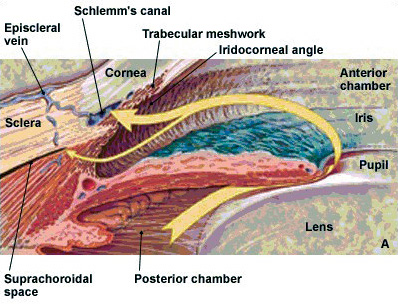

IOP is determined by three factors: (a) the rate of

aqueous humor production by the ciliary body, (b) the resistance to aqueous

outflow across the trabecular meshwork - Schlemm's canal system, and (c)

the level of episcleral venous pressure. In most cases, increased IOP

is caused by increased resistance to aqueous humor outflow; in a minority

of cases, elevated IOP is caused by increased episcleral venous pressure.

Although the causes of glaucoma are still unknown, studies

suggest controlling IOP slows the risk of disease progression.31,32

In fact, elevated IOP is considered to be one of the most important risk

factors for glaucoma.2,3,6

Classification

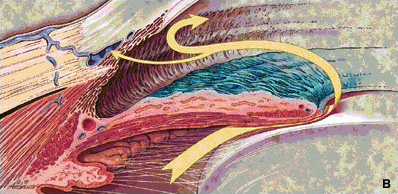

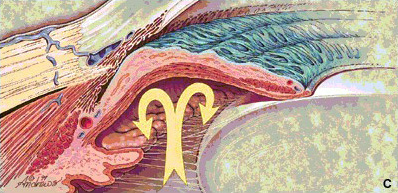

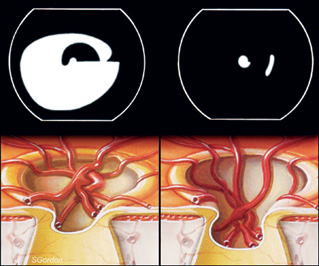

The many types of glaucoma are classified, primarily,

as being of (a) the open-angle or (b) angle-closure type, according to

the manner in which aqueous outflow is impaired. In open-angle glaucoma,

the elevation in IOP is caused by increased resistance in the drainage

channels; whereas in angle-closure glaucoma the obstruction to aqueous

outflow is caused by closure of the chamber angle by the peripheral iris.

Figure

1a: Normal aqueous flow in the anterior and posterior chambers

|

|

Figure

1b: The flow's main resistance is at the trabecular meshwork

in cases of open-angle glaucoma |

|

Figure

1c: In cases of pupil block, the iris bulges forward and the

angle is closed |

|

Further classification describes the disorder as (a)

primary or (b) secondary depending on the absence or presence of associated

factors contributing to the IOP rise (e.g., presence of proliferative

diabetic retinopathy and uveitis, use of topical steroids and following

trauma).

In some cases, the age of the patient at the onset of

glaucoma is also taken into consideration and the condition is then described

as congenital, infantile, juvenile, or adult accordingly.

Assessment

A full assessment will be preformed by an ophthalmologist

once he/she suspects the patient is suffering from glaucoma. The aims

of the initial assessment are:

| |

- |

to determine whether or not glaucoma is

present; or likely to develop (i.e., assess risk factors) |

| |

- |

to exclude or confirm alternative diagnosis |

| |

- |

to identify the underlying mechanism of

damage, so as to guide the choice management |

| |

- |

to begin planning a strategy of management

|

| |

- |

to identify suitable forms of treatment;

and to exclude those which are inappropriate. |

| |

In particular, the following

areas will be recorded: |

| |

- |

Level of IOP |

| |

- |

Gonioscopy (Angle status) |

| |

- |

Optic nerve head morphology |

| |

- |

Perimetry |

Intraocular pressure

The IOP is measured by various kinds of tonometers,

the gold standard of which is called Goldmann Tonometer. It is usually

a kind of slit-lamp mount instrument and designed in a way that the IOP

can easily be measured at the same time as the routine slit-lamp biomicroscopic

eye examination. Unfortunately there is no safe safety-margin below which

any eye can be free of glaucomatous damage. The figure of 21.5 mmHg is

a by-product of statistics (mean+/-standard deviations) using old Western

data base. However, in general, the higher the IOP is, the more is the

likelihood of the presence of glaucomatous damage to an eye.

Gonioscopy

Gonioscopy is crucial for the proper diagnosis of glaucoma.

Furthermore, it is essential for glaucoma treatment in the angle (e.g.,

laser trabeculoplasty). Gonioscopy should be performed on all patients

with glaucoma, on all glaucoma suspects, and on all individuals thought

to have narrow angles.

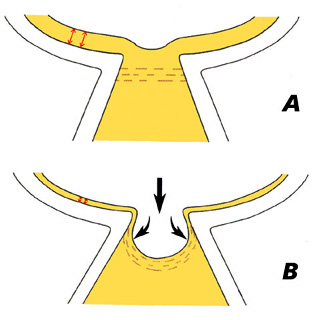

Proper management of glaucoma requires that the clinician

determine whether the angle is open or closed. In angle-closure, the peripheral

iris obstructs the trabecular meshwork, (i.e., the meshwork is not visible

on gonioscopy). The width of the angle is determined by the site of insertion

of the iris on the ciliary face, the convexity of the iris, and the prominence

of the peripheral iris roll. If the angle between the peripheral iris

and the trabecular meshwork exceeds 20o, angle-closure is unlikely.

Optic nerve head morphology

Ophthalmoscopy is used to examine the inside of the

eye, especially the optic nerve. Glaucomatous damage typically appears

as cupping or increased cup-to- disc area ratio. The cup is classically

defined as the white central part of the optic nerve head (optic disc).

The usual average optic disc diameter is about 1.5mm. A cup with a diameter

of more than 0.5mm (resulting in a cup-to-disc ratio of more than 0.3)

is generally considered to be a feature of glaucoma suspects.

| |

| Figure

2a: The pressure effect and progression of cupping |

|

|

| Figure

2b: The progression of cupping and simultaneous deterioration

of visual field |

|

|

In recent years, three new techniques of optic nerve

imaging have become widely available. These are (a) scanning laser polarimetry

(GDx), (b) confocal laser ophthalmoscopy (Heidelberg Retinal Tomography

or HRT), and (c) optical coherence tomography (OCT).

The GDx machine does not actually image the optic

nerve but rather it measures the thickness of the nerve fiber layer on

the retinal surface just before the fibers pass over the optic nerve margin

to form the optic nerve. The HRT scans the retinal surface and

optic nerve with a laser. It then constructs a topographic (3-D) image

of the optic nerve including a contour outline of the optic cup. The nerve

fiber layer thickness is also measured. The OCT instrument utilizes

a technique called optical coherence tomography which creates images by

use of special beams of light. The OCT machine can create a contour map

of the optic nerve, optic cup and measure the retinal nerve fiber thickness.

Over time all three of these machines can detect loss of optic nerve fibers.

Perimetry

Perimetry is performed with either static or kinetic

presentations of the target. Kinetic perimetry (e.g., Goldmann) uses a

moving stimulus of fixed intensity. The stimulus is moved at a steady

rate from a non-seeing area to a seeing area until it is perceived by

the patient. Static perimetry (Humphrey) uses a stationary stimulus of

variable intensity. The intensity is increased until the patient first

recognizes the presence of the stimulus.

| Figure

3a: A normal Humphrey visual field |

|

|

| Figure

3b: A restricted Humphrey field |

|

|

It is important to correlate changes in the visual field with

those in the optic nerve head. If an appropriate correlation is not present,

other causes of visual loss must be considered, (e.g., ischaemic optic

neuropathy, demyelinating disease, pituitary tumor, etc.)

Treatment

The objective

of glaucoma treatment is to maintain functional vision throughout the

patient's lifetime with minimal effect on quality of life. The goal of

intervention is risk factor reduction:

| |

- |

Angle control |

| |

- |

Reducing IOP |

| |

- |

Treatment of predisposing disease/factors

(diabetes mellitus, uveitis, steroids) |

Angle control

There are some situations (PACG and chronic narrow-angle

or angle-closure glaucoma) in which treatment at the angle or structures

near-by may be beneficial. Pilocarpine has the effect of contracting the

longitudinal part of the ciliary muscles and thus helps re-opening a closed

angle. In cases of acute angle-closure glaucoma or narrow-angle glaucoma,

a laser iridotomy (LI) or a laser iridoplasty also helps re-opening a

closed angle and reduces the chance of further angle-closure from happening.

Paediatric glaucomas can sometimes be controlled well with a goniotomy.

But actually it is a drainage procedure although the primary site of interest

is the angle. There are some situations in which a very swollen cataract

may push the iris forward and occlude the angle. In those cases, a simple

cataract surgery may cure the disease.

| Table

1: Mechanism of action of different drug classes |

| Mechanism of action |

Drug Class |

Preparations |

|

| Reduction of aqueous inflow |

Adrenergic agonists |

|

- Brimonidine |

| |

- Apraclonidine |

|

| Beta-blockers |

Non-selective |

| |

- Timolol |

| |

- Levobunolol |

| |

- Carteolol |

| Beta1-selective |

| |

|

- Betaxolol |

|

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors |

Systemic |

| |

- Acetazolamide |

| |

- Methazolamide |

| |

|

- ichlorphenamide |

| |

Topical |

| |

|

|

- Dorzolamide |

| |

|

|

- Brinzolamide |

|

| Increase in aqueous outflow

|

Cholinergics

- Increase trabecular outflow |

|

- Pilocarpine |

| |

- Carbachol |

|

Prostaglandins and other lipid

receptor agonists

- Increase uveoscleral outflow |

|

- Latanoprost |

| |

- Travoprost |

| |

|

- Bimatoprost |

| |

|

- Unoprostone |

|

Reducing IOP

Studies suggest that lowering IOP can help to slow or

stop the likelihood of disease progression.31,32 IOP can be

lowered by reducing the production of aqueous humor or increasing its

drainage "out" of the eye33-35 via (a) medical treatment, (b)

laser therapy or (c) surgery.6,7,33,35,36 Despite wide differences

in practice patterns,36 monotherapy with a topical beta-adrenergic

receptor antagonist (beta-blocker) has attained global acceptance as standard

first-line therapy for POAG.6,34,35,37-39

Unfortunately, topical beta-blockers may not be a long-term

solution. According to a multinational observational study, approximately

50% of patients with POAG or ocular hypertension required either additional

medication or a switch from beta-blocker therapy within 2 years of treatment

initiation.40 These patients with hypertension have high IOP

but there are no cupping of the disc or visual field defect. A certain

portion of them eventually develop other glaucoma features. Some ophthalmologists

regard ocular hypertension as an early state of glaucoma. Inability to

control IOP was the most frequently cited reason for treatment change.

Side effects also hampered the long-term usefulness of nonselective beta-blocker

monotherapy.

| Figure

4a: Percentage of patients requiring a change from nonselective

beta-blocker monotherapy |

|

With the exception of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands,

where more patients undergo laser trabeculoplasty or trabeculectomy after

failure of first-line therapy, the preferred second-line therapy after

beta-blocker monotherapy is either a different monotherapy or combination

therapy. Switching to a different monotherapy is generally recommended

before resorting to combination therapy.6,39 Laser and surgical

procedures are usually used only after medical treatment has failed.2,7,33

| Figure

4b: Treatment algorithm for the management of POAG. Note that these

are only general guidelines.6 |

|

Argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) is a common treatment

procedure for the treatment of POAG in the West. The laser beam opens

the fluid channels (trabeculum) of the eye, helping the drainage system

to work better. In many cases, medication will still be needed. Usually,

half the trabeculum is treated first. If necessary, the other half can

be treated in a separate session another time. This method prevents over-correction

and lowers the risk of increased pressure following surgery. ALT has successfully

lowered IOP in up to 75% of patients treated.

| Figure

5a: Argon laser trabeculoplasty: laser beams are focused and reflected

to the trabeculum by mirrors in a special contact lens |

|

Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) is a new form of

trabeculum laser treatment under multi-center clinical trials. It uses

a combination of laser frequencies that allow the laser to work at very

low levels. It treats specific cells "selectively", leaving untreated

portions of the trabeculum intact. For this reason, it is believed that

SLT, unlike other types of laser surgery, may be safely repeated many

times.

Cyclophotocoaguation (YAG or Diode laser) is a "last-ditch"

procedure to save an eye from severe glaucoma damage not managed by standard

glaucoma surgery. This surgery destroys part of the ciliary body, the

part of the eye that produces intraocular fluid. This procedure may need

to be repeated in order to permanently control glaucoma.

Trabeculectomy may be needed in cases in which both medical

and/or laser treatments fail to lower the IOP to the target level. In

this filtering microsurgery, a tiny drainage hole is made in the sclera

(under a pre-opened partial thickness scleral flap). If successful, the

hole will act as a fistula through which the aqueous humor flows from

the anterior chamber into the sub-conjunctival space, bypassing the highly

resistant trabecular meshwork. As a result, the IOP can be lowered to

a level at which retinal nerve fiber damage is minimized.

| Figure

5b: An opening is made at the trabeculum (T), allowing aqueous to

flow directly from the anterior chamber into the sub-conjunctival

space |

|

In general, glaucoma filtering surgery is successful

in about 70-90% of cases. Occasionally, the surgically created drainage

fistula begins to close (wound healing) and the IOP rises again. This

occurs most often in younger patients. Anti-wound healing drugs, such

as mitomycin-C and 5-FU, help to slow down the "healing". If needed, trabeculectomy

can be done a number of times in the same eye (usually at different sites).

Glaucoma drainage devices are intraocular implants which

allow aqueous to flow from the anterior chamber into a maintained episcleral

space from where it can be absorbed into surrounding blood vessels. There

are a few commercial preparations in the market, such as Molteno, Ahmed,

Baerveldt, etc. It is indicated when there is a very high risk of failure

of trabeculectomy even with anti-fibrotics - these eyes invariably have

severe, refractory glaucoma:

| |

- |

Previously failed trabeculectomies with

anti-fibrotics. |

| |

- |

Prior multiple ocular surgeries with conjunctival

scarring. |

| |

- |

Traumatic, inflammatory or chemically induced

surface scarring. |

| |

- |

Intraocular membrane formation likely to

occlude a non-implant drainage procedure (e.g., irido-corneal endothelial

syndrome, neovascular glaucoma). |

This surgery, and the management of the patient post-operatively

is complicated. Only an ophthalmologist with appropriate training and

experience in glaucoma should perform it.

Conclusion

Life-long medical and ophthalmological follow up is

necessary with or without a good disease control. As a result of its chronic

nature, a good drug compliance and trusting doctor-patient relationship

is essential in achieving the ultimate objective:

"To maintain functional vision throughout the patient's

lifetime with minimal effect on quality of life."

Key messages

- Glaucoma is asymptomatic until in late stages during which severe

irreversible ocular damage already occurs.

- Early detection and referral of suspected cases to eye specialists

by family physicians will help preserve vision, prevent blindness and

improve quality of life.

- Risks factors include old age, family history and the female gender.

- Family physicians can help in promoting the importance of good drug

compliance, regular general and eye follow up visits and good control

of systemic factors eg., Blood pressure and sugar level.

Jackson Woo, FRCS(Glasg),

FHKAM(Ophthal)

Senior Medical Officer,

Department of Ophthalmology, Caritas Medical Centre.

Correspondence to:

Dr Jackson Woo,

Department of Ophthalmology, Caritas Medical Centre, 111 Wing Hong Street,

Sham Shui Po, Kowloon.

References

- National Advisory Eye Council. Vision Research. A National Plan:

1999-2003. Available at: http://www.nei.nih.gov/TextSite/publications/Plan/NEIExecSum/execsumm.htm.

Accessed 19 September 2001.

- Shields MB. Textbook of Glaucoma. 4th ed. Philadelphia,

PA: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:chap 1, 2, 4, 9, 27, 29.

- Flanagan JG. Glaucoma update: epidemiology and new approaches to

medical treatment. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 1998;18:126-132.

- Quigley HA, Vitale S. Models of open-angle glaucoma prevalence and

incidence in the United States. Invest Pohthalmol Vis Sci 1997;38:83-91.

- Quigley HA. Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br J Ophthalmol

1996;80:389-393.

- Hoyng PFJ, van Beek LM. Pharmacological therapy for glaucoma: a review.

Drugs 2000;59:411-434.

- Fiscella RG. Costs of glaucoma medications. Am J Health Syst Pharm

1998;55:272-275.

- Zimmerman TJ, Zalta AH. Facilitating patient compliance in glaucoma

therapy. Surv Ophthalmol 1983;28(suppl):252-257.

- National Eye Institue. Facts about open-angle glaucoma. National

Eye Health Education Program. Available at: http://www.nei.nih.gov/gam/facts.htm.

Accessed 19 September 2001.

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists. The

National Trachoma and eye Health Program, Chapter 8, pp. 82-100, Sydney,

1980.

- Baasanhu J, Johnson GJ, Burendei G, et al. Pervalence and

causes of blindness and visual impairment in Mongolia: a survey of populations

aged 40 years and older. Bull World Health Organization 1994;72:771-776.

- Foster PJ, Oen FT, Machin DS, et al. the prevalence of glaucoma

in Chinese residents of Singapore. A cross-sectional population survey

in Tanjong Pagar district. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:1105-1111.

- Foster PJ, Johnson GJ. Glaucoma in China: how big is the problem?

Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:1277-1282.

- Hong Kong Hospital Authority Statistical Report 2001-2002. Registration

of permanent blindness in hospital authority ophthalmology teams 2001,

p.68. http://www.ha.org.hk

(accessed 27 Sept 2003).

- Tso MOM, Naumann GO, Zhang S. Editorial - Studies of the prevalence

of blindness in the Asia-Pacific region and the worldwide initiative

in ophthalmic education. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:582-585.

- Seah SKL, Foster PJ. Chew PT, et al. Incidence of acute primary

angle-closure glaucoma in Singapore. An Island-Wide Survey. Arch

Ophthalmol 1997;115:1436-1440.

- Wong TY, Foster PJ, Seah SKL, et al. Rates of hospital admissions

for primary angle closure glaucoma Chinese, Malays, and Indians in Singapore.

Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:990-992.

- Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath TJ, et al. Is current eye-care-policy

focus almost exclusively on cataract adequate to deal with blindness

in India? Lancet 1998;351:1312-1316.

- Dandona L, Dandona R, Mandal P, et al. Angle-closure glaucoma

in an urban population in southern India. The Andhra Pradesh eye disease

study. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1710-1716.

- Foster PJ, Baasanhu J, Alsbirk PH, et al. Glaucoma in Mongolia

- A population-based survey in Hovsgol Province, Northern Mongolia.

Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114:1235-1241.

- Wensor MD, McCarty CA, Stanislavsky YL, et al. The prevalence

of glaucoma in the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project. Ophthalmology

1998;105:733-739.

- Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo W, et al. Prevalence of open-angle

glaucoma in Australia. The Blue Mountain Eye Study. Ophthalmology

1996;103:1661-1669.

- Shiose Y, Kitazawa Y, Tsukuhara S, et al. Epidemiology of

glaucoma in Japan - A nationwide glaucoma survey. Jpn J Ophthalmol

1991;35:133-135.

- Leske MC, Connell AM, Wu SY, et al. Risk factors for open

angle glaucoma. The Barbados Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:918-924.

- McNaught AI, Allen JG, Healey DL, et al. Accuracy and implications

of a reported family history of glaucoma: experience from the Glaucoma

Inheritance Study in Tasmania. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:900-904.

- Foster PJ, Machin D, Wong TY, et al. Determinants of intraocular

pressure and its association with glaucomatous optic neuropathy in Chinese

Singaporeans: the Tanjong Pagar Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci

2003;44:3885-3891.

- Tornquist R. Shallow anterior chamber in acute angle-closure. A clinical

and genetic study. Acta Ophthalmol 1953;31(Suppl. 39):1-74.

- Okabe I, Taniguchi T, Yamamoto T, et al. Age-related changes

of the anterior chamber width. J Glaucoma 1992;1:100-107.

- Foster PJ, Alsbirk PH, Baasanhu J, et al. Anterior chamber

depth in Mongolians. Variation with age, sex and method of measurement.

Am J Ophthalmol 1997;124:53-60.

- Mitchell P, Hourihan F, Sandbach J, et al. The relationship

between glaucoma and myopia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology

1999;106:2010-1015.

- Mao LK, Stewart WC, Sjields MB. Correlation between intraocular pressure

and progressive glaucomatous damage in primary open-angle glaucoma.

Am J Ophthalmol 1991;111:51-55.

- Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Comparison of

glaucomatous progression between untyreated patients with normal-tension

glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures.

Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:487-497.

- Vaughan D, Riordan-Eva O. Glaucoma. In: Vaughan D, Asbury T, Riordan-Eva

O, (eds). General Ophthalmology. 15th ed. Stamford,

CT: Appleton & Lange; 1999:200-215.

- Newell FW. Ophthalmology Principles and Concepts. 8th

ed. St. Louis, MO:Mosby-Year Book inc; 1996:379-405.

- Diestelhorst M. Medical treatment of glaucoma and the promising perspectives.

Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 1996;7:18-23.

- Jonsson B, Krieglstein G. Foreword. In: Jonsson B, Krieglstein G,

(eds). Promary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Differences in International

Treatment Patterns and Costs. Oxford, UK: Isis Medical Media Ltd;

1998:vii.

- Kobelt G, Haga A, Gerdtham U-G. Observational study. In: Jonsson

B, Krieglstein G, (eds). Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Differences

in International Treatment Patterns and Costs. Oxford, UK: Isis

Medical Medica Ltd;1998:17-23.

- Cantor LB. Glaucoma. In: Rakel R, (ed). Conn's Current Therapy

2000. Philadelphia, PA:WB Saunders Co; 2000:912-915.

- Camras CB, Toris CB, Tamesis RR. Efficacy and adverse effects of

medications used in the treatment of glaucoma. Drugs Aging 1999;15:377-388.

- Koblet G, Haga A, Gerdtham U-G. Results for the United States. In:

Jonsson B, Krieglstein G, (eds). Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Differences

in International Treatment Patterns and Costs. Oxford, UK: Isis

Medical Media Ltd; 1998:106-126.