|

April 2007, Volume 29, No. 4

|

Original Articles

|

Effectiveness of influenza vaccination among elderly home residents in Hong Kong: a retrospective cohort studyJackie C K Leung 梁靜勤 HK Pract 2007;29:123-133 Summary

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of vaccinating elderly

home residents against influenza on reducing the risk of influenza and related complications

during influenza outbreaks.

Keywords: Influenza, vaccine, elderly 摘要

目的: 評估在流行性感冒爆發期間,為老人院舍長者提供流感疫苗注射已降低流感和相關併發症風險的成效。

主要詞彙: 流行性感冒,疫苗注射,長者。 Introduction Influenza occurs all over the world, with an annual global attack rate estimated at 5-10% in adults and 20-30% in children.1 Epidemics of influenza typically occur during winter in temperate regions. In subtropical regions, a second peak in summer is frequently observed.2 Where infection rates are highest among children, serious illnesses and deaths are more common among persons aged 65 years or above, and persons of any age who have medical conditions that place them at increased risk for complications from influenza.3 In the United States, influenza-associated deaths range between 30 and 150 per 100 000 population aged >65 years.1 Influenza in the elderly causes considerable public health concern. It is more difficult to diagnose influenza in the elderly due to atypical presentation. Once infected, the chance of developing complications is much higher in the frail elders. Also, the closed living environment in the elderly homes and the frequent visits paid by people from the community facilitates the introduction and transmission of infective agents. Consequently, influenza has a major impact on residents of elderly homes, where the attack rates typically range from 20% - 30%.4 Administration of influenza vaccine is the primary method of preventing the disease and its severe complications.5 Influenza vaccine is estimated to be 70% - 90% effective in preventing clinical influenza in healthy adults aged below 65 years, provided there is a good match between the vaccine antigens and circulating viruses.1 Its effectiveness among the elderly is lower,6,7 presumably due to the failure to mount an adequate response to vaccine by the degenerating immune system. In several overseas cohort and case-control studies in the United States and Canada, influenza vaccines offer approximately 33 - 62% protection against influenza, 43 - 66% protection against pneumonia, and 40 - 82% protection against death.8-17 In Hong Kong, the Department of Health (DH) commenced yearly free-of-charge influenza vaccination programme to elderly home residents in 1998. However, evidence for vaccine effectiveness in this particular population was scarce. One unpublished study conducted by DH, in 199918 estimated that vaccine effectiveness in reducing all-cause mortality in the elderly homes residents was in the range of 33 - 55%. However, data on age, sex and chronic medical illnesses were largely incomplete due to missing records. This made adjustment for potential confounding factors impossible. Another study conducted by DH in 200419 estimated that the effectiveness of influenza vaccine was 41% in preventing influenza, 47% in preventing hospitalization, and 53% in preventing pneumonia in influenza outbreaks. Again, data on important confounders was not available. In view of the paucity of evidence, this study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of influenza vaccine in preventing influenza and related complications among elderly home residents, in an attempt to adjust for potential confounding factors. Methods The study areas comprised 5 districts of Kowloon region, namely Kowloon City, Yau Tsim Mong, Sham Shui Po, Wong Tai Sin and Kwun Tong. Located within these districts were 339 licensed elderly homes according to the registry of Social Welfare Department (SWD), which contributed to 38% of the total number of elderly homes in Hong Kong. I recruited those elderly homes that reported influenza-like illness (ILI) outbreaks to DH during 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2005 inclusive. Only confirmed influenza outbreaks, defined as outbreaks that had at least 1 case-patient being tested positive for influenza virus in clinical specimen(s) obtained, were included. Subjects were eligible if they aged 65 years or above.

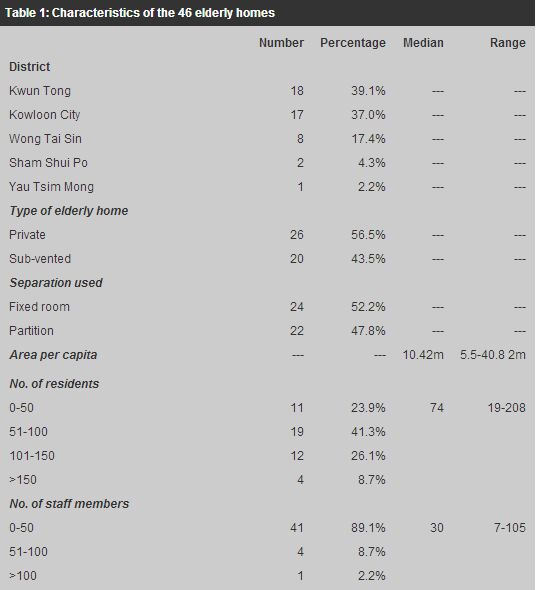

Influenza was defined clinically as an acute illness characterized by fever >38 The exposed group in this study comprised subjects who had not received influenza vaccination from DH or other health care providers in 2004 while the control group comprised subjects who had received influenza vaccination from DH or other health care providers in 2004. Information regarding vaccination was based on its documentation in the elderly home records. For resident having unknown history of influenza vaccination in the preceding calendar year, he/she was regarded as being not vaccinated. Several case-control studies had established that cardiovascular, pulmonary and renal diseases were independent risk factors for the development of elderly home acquired respiratory illnesses.21-24 Conventionally, diabetes mellitus and malignancies were regarded as immunocompromised states. In view of this, the underlying medical illnesses were grouped into 5 broad categories: cardiovascular diseases (including ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, valvular heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease), pulmonary diseases (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and interstitial lung disease), renal diseases (including chronic renal failure), diabetes mellitus, and malignancies. A standardized questionnaire modified from the questionnaire OAH version 030804 used by DH during outbreak investigation was employed to collect data from the elderly homes once an influenza outbreak was defined in the elderly home. Data collected included residents' age, sex, comordities, and symptoms of influenza and vaccination history in the preceding calendar year. A trained public health nurse gave briefing to the staff members of the elderly homes before they filled in the questionnaires. The occurrence of influenza was identified by the self-administered questionnaires. The occurrence of pneumonia, hospitalization and death were identified from the hospital records. The causative agent was verified from the laboratory records of case-patients who had clinical specimens being obtained. The sample size calculated for this study was a minimum of 473 persons in each study group, given a 5% type I error and 80% power. The data were analyzed at 2 levels: the individual level and home level. At the individual level, a total of 13 variables were included in the analysis. These were type of elderly home (private or sub-vented), area per capita, separation used (partitions of fixed rooms), overall vaccine uptake of residents, overall vaccine uptake of staff, age, sex, vaccination status, and the presence of chronic medical conditions (total 5). Categorical variables were compared by Pearson chi- square test between the 2 groups. Continuous variables were compared by independent t-test if they were normally distributed and Mann-Whitney U test if they were not normal. Univariate analysis was first performed to estimate the crude relative risk of each variable followed by multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the adjusted relative risk. Vaccine effectiveness (VE) was calculated as one minus the relative risk in vaccinated subjects, multiplied by 100%, i.e. VE = (1-RRvac/RRunvac) x 100%. At the elderly home level, I used multiple linear regressions model to investigate the association between 13 variables and influenza attack rate, hospitalization rate and pneumonia. The variables were type of elderly home (private or sub-vented), area per capita, separation used (private or sub-vented), overall vaccine uptake of residents, overall vaccine uptake of staff, number of residents, number of staff, proportion of residents having chronic medical conditions, and the location of the elderly home. All data were analyzed by SPSS software (version 13). All statistical analyses were performed with a level of significance of 0.05. Results In 2005, DH received notification of 96 ILI outbreaks in the aforementioned 5 districts in Kowloon. 50 outbreaks occurring in 50 different elderly homes were classified as confirmed ones. As vaccination records were missing from 4 elderly homes, they were excluded from the study. As a result, 46 different elderly homes with confirmed influenza outbreaks were included in the study. Elderly home level About 3 quarters of influenza outbreaks occurred in elderly homes located in Kwun Tong (39.1%) and Kowloon City (37%). Of the 46 elderly homes, 26 (56.5%) were run by private organizations while 20 (43.5%) received subvention from the Government. The median area per capita in these homes was 10.42m, which was well above the minimum of 6.52m required by the Social Welfare Department (SWD). The median number of residents per home was 74 (range 19-208) and staff per home was 30 (range 7-105). The median vaccine uptake of residents was 93.4% while that of the staff was 54.3%. The median percentages of residents having chronic medical conditions were: 71.7% for cardiovascular disease, 20.6% for diabetes mellitus, 10.6% for pulmonary disease, 5.6% for malignancy and 3.8% for renal disease. The median time to influenza outbreak was 137.5 days (range 0-177). The median duration of follow-up for the outbreaks was 13 days (range 8-35). 45 outbreaks (97.8%) were due to influenza A, all belonged to H3N2 strain, and 1 (2.2%) was due to influenza B. The median influnza attack rate, hospitalization rate and pneumonia rate were 7% (range 1.8-36.8%), 40% (range 0-100%) and 0% (range 0-100%) respectively (Table 1).

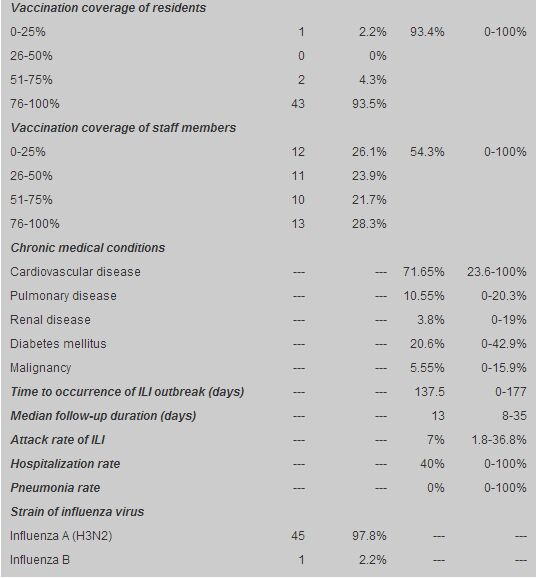

A higher uptake of influenza vaccine by the residents was not demonstrated to be associated with lower influenza attack rate, hospitalization rate and pneumonia rate. Variables that were significantly associated with higher influenza attack rate were residing in private homes (p=0.041) and a higher area per capita (p=0.048). Residing in Wong Tai Sin was significantly associated with higher hospitalization rate (p=0.011), while residing in Wong Tai Sin (p=0.01) or Yau Tsim Mong (p=0.007), and homes with a higher % of residents having pulmonary diseases (p=0.013) were significantly associated with higher rate of pneumonia (Table 2).

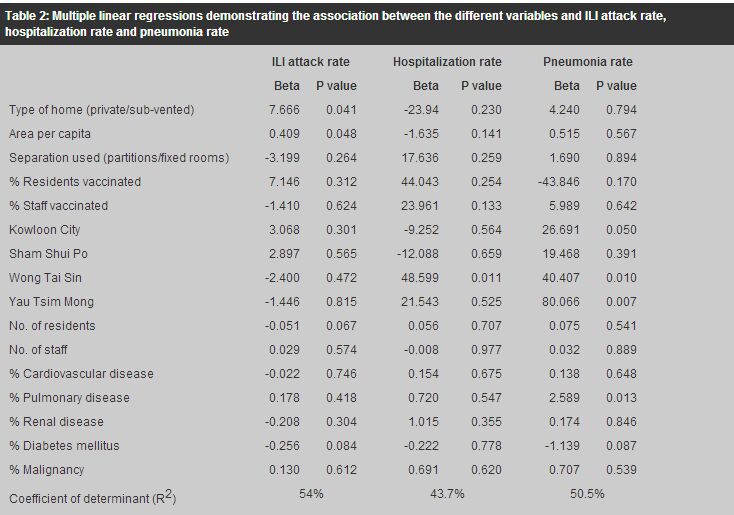

Individual level There were 3177 residents participated in the study. The mean and median age was 83 years (range 65-107, SD 7.6). 2133 (67.1%) were females and 1044 (32.9%) were males. There were 2943 (92.6%) vaccinated and 234 (7.4%) unvaccinated subjects. Regarding the baseline characteristics of the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, a higher proportion of the former were females (67.7% vs. 59.8%, p=0.013). The mean age of the former was also slightly higher (83 years vs. 82 years, p=0.032), though the clinical significance was likely to be minimal. The proportion of vaccinated residents in homes where vaccinated residents lived was significantly higher than their unvaccinated counterparts (91.3% vs. 88.6%, p<0.001). Similarly, the proportion of vaccinated staff in homes where vaccinated residents lived was also significantly higher than the unvaccinated residents (52.9% vs. 47.3%, p=0.009) (Table 3).

A total of 210 influenza cases were recorded, constituting 6.6% of the total study population. 103 case-patients (49%) had nasopharyngeal swabs taken, of which 97 (46.2%) were positive for influenza virus. 16 influenza case-patients were unvaccinated while 194 were vaccinated, giving a relative risk of 1.04 (p=0.884). Among the 210 influenza case-patients, 100 (47.6%) required hospitalization. 9 of whom were unvaccinated while 91 were vaccinated, giving a relative risk of 1.46 (p=0.510). 19 (19%) case-patients were complicated by pneumonia, of whom 1 was unvaccinated and 18 were vaccinated, giving a relative risk of 0.58 (p=0.616) (Table 3). There was no mortality recorded. Vaccinated and unvaccinated also did not significantly differ in the risks of acquiring influenza, hospitalizationa and pneumonia after adjusting for confounding factors (Table 4).

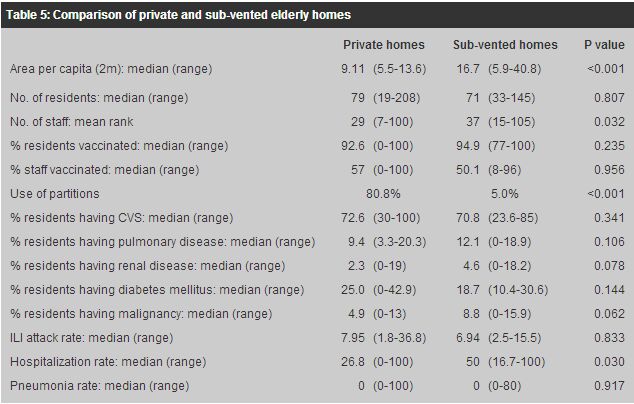

Discussions This study did not demonstrate that influenza vaccination reduced the risk for influenza among elderly home residents. Several reasons could account for this. First, influenza case-patients were identified during outbreaks in this study. However, notification of ILI outbreaks to Centre for Health Protection (CHP) by the elderly homes was on a voluntary basis and was subjected to under-reporting. Those homes that did not report outbreaks to CHP might differ in many ways from those who did for reasons that could not be elucidated from the study. This could introduce selection bias. About half of the influenza outbreaks (46 out of 96) were unable to be confirmed due to the absence of clinical specimens being obtained from the ill residents. How many of these were due to influenza viruses was unknown. Excluding these homes from the analysis would lose valuable information. Besides, the current notification system could only pick up case-patients in the midst of an outbreak, missing out those sporadic cases. As a result of these reasons, the true burden of influenza in elderly homes was under-estimated. Second, classification of residents with unknown history of vaccination as being unvaccinated introduced misclassification bias and might have shifted the study results towards null. Third, only 49% of ill residents who fulfilled the clinical case definition of influenza had clinical specimens obtained. The remaining 51% of case-patients might have contracted some other respiratory viruses. Since influenza vaccine could only protect against influenza viruses, inclusion of those case-patients without laboratory confirmation might have diluted the effectiveness of vaccine. Fourth, the study was underpowered since at least 473 subjects were required in each group. Similarly, influenza vaccination was not shown to be protective against hospitalization and pneumonia in elders having contracted influenza. The main reason was a relatively short follow-up duration in each outbreak, which was only 8 days. Hospital admissions, pneumonia, or deaths occurring beyond the surveillance period was unable to be identified. As pneumonia could occur up to 60 days after the onset of influenza symptoms according to one overseas study,9 underestimation of the incidence of hospitalization and pneumonia was likely. In this study, it was shown that the individual risk of influenza increased with increasing age and in residents having renal diseases. The individual risk of influenza related hospitalization increased with increasing age and male sex. In addition, at the home level, the pneumonia rate among influenza case-patients was positively associated with the proportion of residents having pulmonary diseases. All the above findings were consistent with those cited in several overseas studies.21-24 On the other hand, individuals had a lower risk of acquiring influenza if they lived in homes that had a higher proportion of vaccinated residents and a higher utilization of partitions. The former was in line with the concept of herd immunity.3 The latter might be difficult to explain. One possible explanation might be that within each compartment separated by partitions, usually only 1 or 2 residents lived inside. On the contrary, where regular rooms were provided, each was able to accommodate more residents, sometimes up to 10, depending on the size of the room. The provision of rooms might actually increase the chance of interaction between the residents, which facilitate the spread of infection. The results showed that 'home' factors played a significant role in association with one's risk for influenza and related complications. Residing in private elderly homes was demonstrated to be associated with an increased individual risk for influenza, a higher overall attack rate during influenza outbreaks, but a decreased likelihood of hospitalization once becoming infected. Private homes differed from sub-vented homes in a number of ways: they had a lower median number of staff, a higher utilization of partitions and smaller area per capita (Table 5). Was it the case that a lower number of staff meant a lower level of care and attention for residents? Was it the case that a higher utilization of partitions and a lower median area per capita meant that the environment was overcrowded? Conclusions could not be drawn at this stage and further studies would be worthwhile to explore the reasons behind. The lower individual likelihood of hospitalization in private homes had to be interpreted with caution too. Hospital admission was determined by multiple factors, including the severity of illness, the availability of skilled nursing care in the elderly homes, the policy of the elderly homes, social pressure exerted by the relatives of the case-patients and the admitting policy of the hospitals that the case-patients were attending. Therefore, hospital admission itself might not be a good proxy for the severity of influenza.

This study was the first conducted in the local setting to include comordities and various elderly home factors in the statistical models. The retrospective cohort study design was appropriate for evaluating vaccine effectiveness and provided the strongest evidence among all observational studies. However, this study had several limitations. First, only elderly homes in 5 districts in Kowloon were recruited. This hampered the representativeness and generalizability of study results. Second, since only influenza cases during influenza outbreaks were identified and all outbreaks were voluntarily reported, the true incidence of influenza could be under-estimated. Third, not all cases meeting the clinical case definition of influenza were confirmed by laboratory investigation. The low rate of confirmation (46.2%) led to the inclusion of respiratory illness caused by viruses other than influenza viruses and dilution of study results. Fourth, the short follow-up duration under-estimated the true incidence of influenza related hospital admissions, pneumonia and deaths. Fifth, the sample size did not allow the achievement of 80% statistical power, given a 5% type I error. Conclusion In short, this study failed to demonstrate the protective effect of influenza vaccine against influenza and its complications during outbreaks. Environmental factors might have played a more significant role. Further research to explore these was warranted. Acknowledgements I would like to give my sincere thanks to Prof Ignatius Yu and Dr Tian Linwei who have given me valuable advice and tremendous support in writing this article, which was completed during the Master of Public Health programme of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Key messages

Jackie C K Leung, MBChB (CUHK), MRCP (UK), MPH (CUHK)

Medical & Health OfficerMedical & Health Officer Department of Health. Correspondence to : Dr Jackie C K Leung, Tobacco Control Office, 18/F & 25/F, Wu Chung House, 213 Queen's Road East, Wan Chai, Hong Kong.

References

|

|