|

April 2007, Volume 29, No. 4

|

Update Article

|

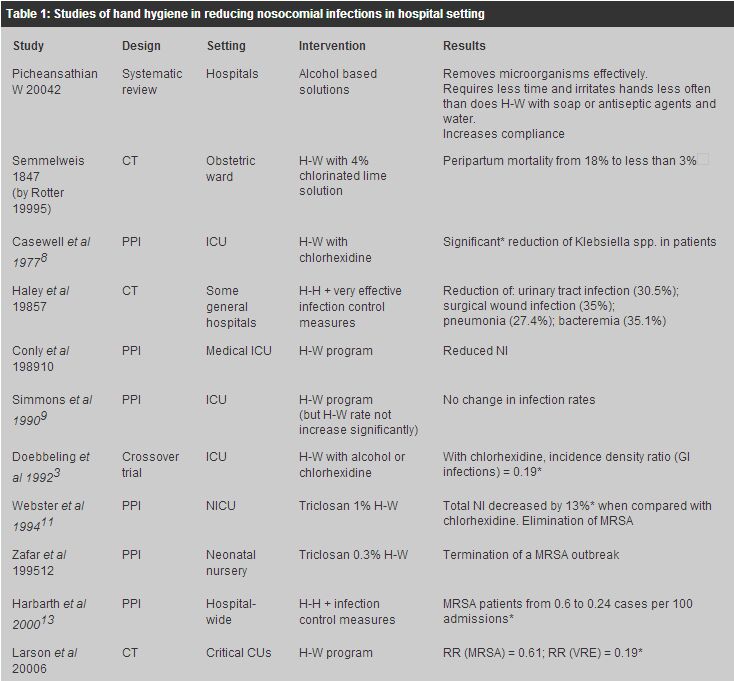

A review of the evidence for hand hygiene in different clinical and community settings for family physiciansJohn W K Yeung 楊永堅, Wilson W S Tam 談維新, Tze-wai Wong 黃子惠 HK Pract 2007;29:157-163 Summary This paper discusses the evidence of hand hygiene (mainly hygienic hand antisepsis) in reducing infections in different settings. In the hospital setting, there is convincing evidence that hand hygiene is effective in reducing nosocomial infections such as urinary tract infection, pneumonia, surgical wound infection and sepsis of in-patients, and in reducing the incidence rates of infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). In long-term care facilities, there is limited evidence to prove whether hand hygiene is effective or not in reducing infections. In institutions such as schools, it is evident that hand hygiene is effective in reducing gastrointestinal illnesses and probably respiratory illnesses among healthy children and young adults. In the community, it is evident that hand hygiene is effective in reducing diarrhoea among healthy individuals within families. Unfortunately, despite the above evidence, doctors are constantly reported to have poor compliance in many studies. Therefore it is important for doctors to improve their compliance in hand hygiene whether they practise in hospitals or in their own clinics. 摘要 本文討論在不同環境下,手部衛生﹝主要是衛生性手部消毒﹞對減少傳染病的證據。在醫院環境, 已有令人信服的證據顯示手部衛生能有效減少醫院內的感染。例如:尿道炎,肺炎,手術傷口感染, 及膿毒症;而且抗甲氧苯青霉素(methicillin)金黃色葡萄球菌及抗萬右霉素(vanomycin)腸道球菌的出現也有減少。 在長期護理院舍,仍未有足夠研究證明手部衛生能否減少院舍內的感染。在學校等團體機構, 已證實手部衛生能有效地減少兒童及青少年的腸胃疾病,而對呼吸道疾病也可能會有幫助。在社區, 手部衛生能有效減少健康家庭成員的肚瀉疾病。雖然如此,可惜研究卻經常發現醫生對手部衛生的遵從性欠佳。 所以,無論在醫院或診所內,醫生都應該改善在手部衛生的遵從。 Introduction Hand hygiene is a general term referring to any action of hand cleansing for the purpose of physically or mechanically removing dirt, organic materials or microorganisms.1 Microbiologically, hand hygiene can be broadly classified into two categories: hygienic hand antisepsis and surgical hand antisepsis. Hygienic hand antisepsis refers to cleansing of hands with either an antiseptic handrub or antiseptic hand wash to reduce the transient microbial flora without necessarily affecting the resident skin flora. Persistent activity against transient microbial flora is not necessary. Surgical hand antisepsis refers to cleansing of hands with antiseptic hand wash or antiseptic handrub pre-operatively by the surgical team to eliminate transient and reduce resident skin flora.1 Such antiseptics often have persistent antimicrobial activity. A great variety of health care workers such as doctors, nurses, nurse assistants, physiotherapists and occupational therapists are expected to perform adequate hygienic hand antisepsis during patient care. On the other hand, individuals should be educated to improve their hand hygiene for disease prevention at the community level. We are going to discuss the evidence of hand hygiene (mainly hygienic hand antisepsis) in reducing infections in hospitals, long-term care facilities (LTCFs), schools and community settings. Hygienic hand antisepsis is very important to family physicians as they may practice in hospitals or visit the LTCFs such as old age homes and provide medical cares for the elderly residents. They can promote hand hygiene in schools or the community through education in order to prevent and control communicable diseases. Surgical hand antisepsis is also relevant to family physicians when performing operative procedures (usually in their clinics). However, we shall focus on hygienic hand antisepsis in this paper as operative procedures are uncommon in primary care setting. Evidence of hand hygiene in hospital setting There are plenty of studies showing evidence that good hand hygiene reduces health care-associated infections (HCI) or nosocomial infections (Table 1). A systematic review by Picheansathian2 reported that alcohol-based antiseptic used in hospitals could remove microorganisms effectively. The use of waterless antiseptic handrub also increased hand hygiene compliance among health care workers. The reasons for the increased compliance may be due to less time required for its use and less hand irritation when compared with hand washing with soap or other antiseptic agents and water.

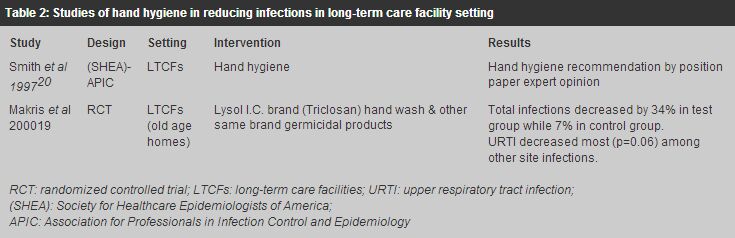

Evidence from five trials (a crossover trial, an open trial and three controlled trials3-7) showed that nosocomial infections could be reduced if hand hygiene programme was implemented properly. The pioneer of hand hygiene trial can be dated back to Dr Semmelweis.5 He showed that hand washing with 4% chlorinated lime solution when performing delivery reduced peripartum death from 18% to less than 3%. However chlorinated lime is an irritant to skin and is no longer used nowadays. A large study7 of a representative sample of US general hospitals showed that very effective infection surveillance and control programmes including hand hygiene reduced urinary tract infection by 30.5% (18.7% - 40.6%), surgical wound infection by 34.9% (18.5% - 48%), pneumonia by 27.4% (7.9% - 42.7%), and bacteremia by 35.1% (19.7% - 47.6%). Other trials done in intensive care units (ICU) or similar settings3,4,6 reported similar results. They reported significant reductions in nosocomial infections, respiratory tract infections, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) occurrence if hand hygiene programme was implemented. In one trial,6 the recovery rate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was also reduced although it did not reach statistical significance. Apart from the above five trials, there are 11 pre- and post-intervention studies8-18 on the effectiveness of hand hygiene in reducing nosocomial infections. Nearly all studies showed reductions (either significant or insignificant) in health care-associated infections. The study9 with no change in infection rates also showed no improvement in hand washing compliance among health care workers between pre- and post-intervention periods. Four studies11,13-15 reported a reduction in the incidence rates of infection with MRSA and one12 reported a termination of MRSA outbreak in a neonatal nursery. Apart from MRSA and VRE, Klebsiella spp. was also reported to be significantly decreased after hand washing with chlorhexidine solution.8 It seems that the greater the compliance of hand hygiene attained, the larger the reduction in nosocomial infections. For instance, when hand hygiene compliance increased by about 1.5 to 2.8 times, the reductions in nosocomial infections were around 40% to 45%.14,17,18 When hand hygiene compliance increased by more than threefold, the reduction in nosocomial infections was reported to be 64%.10 Although many studies in hospital settings reported a reduction in nosocomial infections, it should be reminded that the nosocomial infections reported in these studies might not be the same. In adult ICU or similar settings, the outcome measures of nosocomial infections included catheter or non-catheter related urinary tract infections or bacteremia, ventilator or non-ventilator related pneumonia, and surgical wound infections. In neonatal ICU or similar settings, the outcome measures of nosocomial infections were pneumonia, necrotizing entercolitis, and CNS infections. Evidence of hand hygiene in long-term care facilities Compared with hand hygiene research in hospitals, there were very few similar studies done in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) (Table 2). A cluster randomized controlled trial19 of eight private and free-standing old age homes (OAHs) found that the total infection rates decreased insignificantly by 34% in the intervention group but only 7% in the control group. Interestingly, upper respiratory tract infection decreased the most, and nearly reached statistical significance (p=0.06) when compared with other common infections in LTCFs such as gastrointestinal infections, genitourinary tract infection, lower respiratory infection, and cutaneous infection.

Apart from the above trial, there was a position paper20 from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiologists of America (SHEA) Long-Term-Care Committee and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) Guidelines Committee. They recommended that in general, hand washing with bar or liquid soap is adequate in LTCF. Hand washing with an antiseptic agent is recommended before invasive procedures such as placement of an intravenous or urinary catheter. Alcohol-based handrubs are recommended only when hand washing facilities are not accessible. However, they did not recommend when health care workers should clean their hands, such as between every patients or between every physical contacts. The hand hygiene guideline for hospitals may not be totally suitable for LTCFs. The reason is that in hospitals, all residents are patients but in LTCFs, the residents are a mixture of healthy elderly and patients. Finally, the major limitation of hand hygiene and infection control programmes in long-term care facilities is the limited number of studies available in support of the effectiveness of these programmes or their components. Therefore it is important to further evaluate infection control programmes in these settings, and to ensure optimal effectiveness and cost-efficiency. Evidence of hand hygiene in institutional settings The institution setting can be further subdivided into children institutions such as schools and adult institutions such as colleges and military centres. In Table 3, three randomized controlled21-23 trials and three controlled trials24-26 reported reductions in upper respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses in children after a hand hygiene intervention programme in day care centres or elementary schools. For adult institutions, one controlled trial27 found significant decrease in symptoms of upper respiratory infection among college students living in residential halls. Another pre- and post-intervention study28 reported a significant reduction of respiratory illnesses by 45% among young and fit adults in a military training centre after the intervention of a hand washing programme.

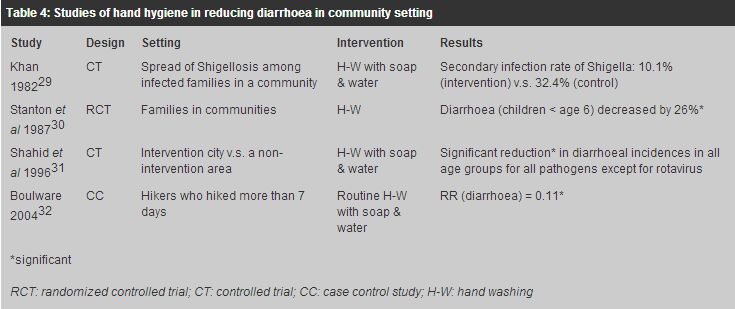

Master et al24 reported a substantial protective effect of hand washing in elementary schools within a period of 37 school days. The absenteeism as a result of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms was significantly reduced in school children when they were scheduled to wash their hands at least four times a day (relative risk = 0.43). All studies21-24 measuring gastrointestinal illnesses as their outcomes reported a decrease in the incidence of GI illnesses or symptoms after hand hygiene intervention. Reductions in GI illnesses or symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhoea seemed to be more consistent. However, the evidence in hand hygiene in reducing respiratory illnesses seems to be more controversial. Significant reductions in respiratory illnesses were observed in three studies.25,27,28 By contrast, three studies reported insignificant results.22-24 In a study26 measuring all absenteeism due to colds and GI illnesses as the health outcome, a significant decrease in the incidence of both conditions was found after hand hygiene implementation. It is clear from the above studies that hand hygiene programme is an important means to reduce GI illnesses and possibly respiratory illnesses in institutions of children or adults. Evidence of hand hygiene in community settings In community settings, all the studies29-32 measured diarrhoea as their outcome after hand hygiene intervention (Table 4). Respiratory illnesses or associated symptoms were not recorded in these studies. A randomized controlled trial30 and a non-randomized controlled trial31 reported significant reductions in diarrhoeal diseases while another trial29 found a lower secondary infection rate of Shigella spreading among infected families of primary cases. There was a case control study32 that reported a significantly lower rate of diarrhoea (7%) among hikers with routine hand washing with soap and water after urination and defecation than with less ('sometimes', 'rarely' or 'never') hand washing (61%). A relatively large study in Bangladesh by Shahid et al31 found a marked (2.6 times) reduction in diarrhoeal episodes in the area with intervention during the observation period. In this study, a significant reduction in the incidence of diarrhoea was observed in all age groups for all pathogens except rotavirus.

Poor hand hygiene compliance of doctors Although there is much evidence to show the effectiveness of hand hygiene in the prevention and control of infections, doctors unfortunately are notoriously inadequate in their compliance with hand hygiene compared with other health care professions such as nurses, nursing assistants and other health care workers.14,33-35 One study36 found that doctors in surgery, intensive care unit, anaesthesiology and emergency medicine specialties are poor in hand hygiene compliance compared to those in internal medicine, paediatrics, geriatrics and other specialties. Poor hand hygiene compliance may be observed among medical students. Feather et al37 reported that medical students had surprisingly poor hand washing behaviour after neurological examinations of the lower limbs of patients (for example, after touching the groins and feet of the patients). Only 8.5% of students washed their hands after patient contact, although this figure rose to 18.3% with the aid of hand washing signs. Hand hygiene compliance of family physicians, especially those running private clinics, has not been reported in previous studies. In Hong Kong, as a result of limited space, some private clinics even do not have a wash hand basin (personal communications with some private general practitioners)! The general practitioners need to use the wash hand basin in the nearby public toilets, e.g., inside the mall. For general practitioners who do not have a wash hand basin in their clinics, it will be very difficult for them to improve their hand hygiene compliance. Unlike in hospitals, hand hygiene in clinics cannot be easily recorded and studied. One might reasonably conclude that good hand hygiene reduces infection not only in hospital settings but also in the primary care setting, despite possibly quantitative differences in the magnitude of the effectiveness. Therefore, family physicians themselves should always keep in mind to practise good hand hygienic for their patients' benefit. An accessible wash hand basin for doctors themselves and their nursing assistants is essential for every clinic. Anti-septic handrubs should be available for doctors, nurses and their patients as well. Conclusion Hand hygiene (or hygienic hand antisepsis) has been demonstrated to be effective in the prevention and control of infections in different settings in our community. The only well-known and relatively common disadvantage is dryness of hands. Rarely, or allergy may result from the use of antiseptic solutions for hand washing. This problem is by and large solved with the use of waterless antiseptic handrub that contains emollient. The introduction of pocket-sized handrub can decrease the time required for hand washing in wash hand basins in busy clinical settings. The most difficult task that remained unresolved seems to be the change in behaviour. How can we improve the hand hygiene compliance among health care workers, in particular, doctors in the hospital and LTCF settings, and in individuals in institutions and the community? Doctors should improve and maintain their hand hygiene compliance whether they practise in hospitals or in their own clinics. Family physician should have an extra responsibility in promoting and educating the public, and, in particular, workers in institutions about the importance of hand hygiene. Key messages

John W K Yeung, MBBS(HK), MSc, PDip

Researcher in Social Medicine, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Wilson W S Tam, PhD, MPhil, BSc Research Assistant Professor Nethersole School of Nursing, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Tze-wai Wong, MBBS(HK), MSc, FHKAM(Community Medicine), FFPH Professor Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Correspondence to : Dr John W K Yeung, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 4th floor, School of Public Health, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong. Email : jwkyeung@cuhk.edu.hk

References

|

|