|

February 2007, Volume 29, No. 2

|

Update Articles

|

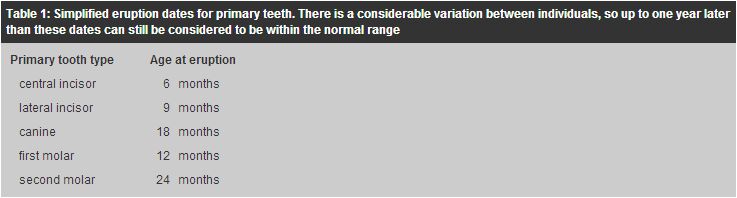

The importance of the primary dentition to children - Part 1: consequences of not treating carious teethNigel M King, Robert P Anthonappa, Anut Itthagarun HK Pract 2007;29:52-61 Summary Humans are diphyodonts, which means that they have two successive sets of teeth: primary and permanent. The primary teeth are important in a child's life as they help in mastication, in speech, contribute to aesthetics and preserve the integrity of the dental arches, finally guiding permanent teeth into their correct positions. Dental caries (decay) which is avoidable, remains a common chronic disease of early childhood with an occurrence rate five times higher than that of asthma and seven times higher than that of allergic rhinitis. Untreated carious teeth in young children frequently lead to pain and infection, necessitating emergency visits to the dentist. Carious teeth in early childhood are not only indicative of future dental problems, they also adversely affect growth and cognitive development by interfering with nutrition, sleep and concentration at school. In addition, they may have a significant impact on an individual's quality of life. Primary teeth are not always given a high priority although physicians and health policy-makers have an interest in playing an active role in children's oral health, owing possibly to lack of simple well-defined practical guidelines to follow when performing dental screenings and other activities relating to the infant's oral health. Also, many parents are unaware of the importance of primary teeth; consequently, dental attendances before the age of two years are uncommon. They consider primary teeth to be only temporary and think that related problems are rarely life-threatening. Intervention to prevent or arrest dental caries should focus on reducing the availability of refined carbohydrates (substrate), reducing the microbial burden (causative organism), increasing the resistance of the teeth (host) to caries, or a combination of these approaches. Nevertheless, dental caries can be effectively treated using various restorative materials with suitable pain control measures. This is possible if proper advice and referral is made by medical practitioners who have early and often frequent contact with young children. There seems to be no logical reason for leaving carious primary teeth untreated in a child's mouth. Early recognition and timely referral of infants and young children with dental caries is critical in preventing the unpleasant complications. Primary care providers who have contact with children are well placed to offer anticipatory advice to reduce the consequences of dental caries. 摘要 人體擁有兩期牙齒,依次序為乳齒及恆齒。乳齒對兒童很重要,它幫助咀嚼、語言、提供美觀的外貌,保持齒弓的完整, 和引導恆齒生長在正確的位置。齲蛀(蛀牙)是可避免的,但它仍是幼兒常見的慢性疾病,其病發率是哮喘的五倍和敏感鼻炎的七倍。 幼童的齲蛀經常會因引起痛楚和感染而需要緊急牙科治療。它會導致將來牙患。它還可以影響兒童的營養、睡眠和上課時的專注力, 從而對生身體和智能的成長造成不良後果。同時,也會顯著地影響生活質素。雖然醫生和醫療決策者已積極地推廣兒童口腔衛生, 但乳齒的重要性仍未受到大眾重視,這可能是由於為兒童進行牙齒健康普查或相關的健康活動時,未有為家長提供簡單而清晰的指引。 很多父母都未知道乳齒的重要性,所以兩歲以下兒童接受牙科檢查的情況並不普遍。他們認為乳齒是暫時的和覺得相關疾病很少有危險性。 預防和遏止齲蛀惡化,應注重減少純淨碳水化合物(底物)在口腔內積聚,減少微生物數量(病原),和增強牙齒(宿主)對齲蛀的抵抗力。 然而齲蛀可採用不同的修復物料和鎮痛方法有效地治療。它的可能性有賴經常接觸幼童的醫生能及早作出建議和轉介。 似乎並無甚麼原因可讓齲蛀的乳齒留在兒童的口腔而置諸不理,不加以治療。為患上齲蛀的嬰兒和幼童及早確診和作出適時轉介是預防併發症的關鍵。 Introduction Humans are diphyodonts, which means that they have two successive sets of teeth: primary and permanent. It could be said that primary teeth are probably more important to children than permanent teeth are to adults. Why is this? The primary teeth are also referred to as deciduous, milk or baby teeth. Of the twenty primary teeth, ten are present in both arches (maxillary and mandibular), and they are classified into three main types; incisors, canines and molars. The teeth begin to develop at 6 weeks of intra-uterine life and a tooth does not emerge into the oral cavity until at least two thirds of the root has formed. They begin to erupt when the child is six months old and finish erupting when the child is approximately two years of age (Table 1), which means that young children are in an active state of teeth eruption from approximately six months until almost three years of age.1 The primary incisor teeth are functional in the mouth for approximately five years, while the primary molars are functional for approximately nine years. In addition to providing a proper chewing surface until 11 or 12 years of age, normal healthy primary teeth (Figure 1) help in speech, contribute to aesthetics and form a template that allows the oral cavity to develop appropriately. Without the primary teeth, the permanent teeth which replace them, cannot assume their proper positions in the dental arch because they are guided into their final positions by the preceding primary teeth.

There are 32 teeth in the permanent dentition that begin to erupt when the child is five years of age and continue until adolescence. At approximately 6 years of age, the maxillary and mandibular first permanent molars and the mandibular permanent incisors begin to erupt. Between the ages of 6 and 12 years of age, children have a mixture of permanent and primary teeth. This is known as the mixed dentition stage. By the age of 12 years most children have all of their permanent teeth, except for their third molars (wisdom teeth), (Table 2). The permanent teeth are classified into four types namely incisors, canines, premolars and molars. It is important to note that while the eruption times vary from child to child, the same as growth rates of children vary, the teeth erupt not simply just one tooth following the one adjacent to it, but also in a standard sequence (Table 1). Therefore, extraction of a primary tooth disrupts the sequence and can consequently lead to malocclusion in the permanent dentition.

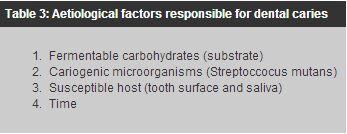

Regardless of the fact that dental caries is principally avoidable, it is the most common of chronic diseases of childhood.2 In USA it occurs at a rate, five times greater than that of asthma and seven times greater than that of allergic rhinitis.2,3 According to the statistics released by the first population-wide Oral Health Survey 2001,4 there were 76,100 children aged 5 years enrolled in local kindergartens and child care centres in Hong Kong. The level of dental caries (tooth decay) as measured by the dmft (decay experience) index showed a mean dmft value of 2.3 with 91.3% of the decayed teeth being untreated. In addition, 23.6% of the children were considered to be at high risk, as this group had around 78% of all the teeth affected by dental caries. The primary teeth that are most susceptible to dental caries are the central incisors and second molars in the maxilla and the first molars in the mandible. Although oral disease is a universal problem, it is often a low priority for health care policy-makers; furthermore a number of parents are ignorant of the importance of primary teeth in their children, so they leave carious teeth untreated unless their child complains of pain. They consider the primary teeth to be only temporary and the related problems non-life threatening. This approach is unwise and incorrect because dental caries can result in several highly undesirable problems. Interestingly, in a recent study in Macau, most caregivers and even medical practitioners considered that carious primary teeth should not be restored.5 This could be due to insufficient knowledge about the role that primary teeth play in the development of the permanent dentition and their adverse effects on individual permanent teeth. While dental caries remains the most prevalent unmet health care need of children,6 low quality dental care can also compromise the functions of primary teeth. Hence, it is proposed in this paper to discuss what the adverse effects are of neglecting carious primary teeth. Early childhood caries Dental caries in infants and young children known as early childhood caries (ECC), (Figures 2 and 3) may be defined as at least having one carious lesion affecting a maxillary anterior tooth in preschool-aged children.7 Dental caries is an infectious disease that is modifiable by the diet. It has several important aetiological factors, which are inter-related and are important in the initiation and progression of the disease process. The factors are: fermentable carbohydrates (substrate), cariogenic microorganisms and the susceptible host (i.e. the tooth surface and saliva) (Table 3) The inter-relationship of these factors was first described by Paul Keyes.8 The Keyes diagram inherently contains the dimension of time, in that an infection needs to be active for a period of time to exert an influence.

Sugars (sucrose, fructose and glucose) and other fermentable carbohydrates (highly refined flour, etc.) play a role in the initiation and progression of dental caries.9 Sucrose is considered to be the most important substrate because, when metabolized by cariogenic bacteria, it produces dextrans which promotes and enhances bacterial adhesion to teeth.10 The frequency of sucrose intake is more important than the total amount consumed.11 Streptococcus mutans is the principal microorganism involved in the development of caries in both children and adults.12 Several studies have revealed that the younger a child is when they acquire Streptococcus mutans, the more caries they will experience.13 Generally, such colonization is the result of transmission of these organisms from the child's primary caregiver, usually the mother.14 A recent study showed that by 24 months of age most children will have mouths that are colonized by Streptococcus mutans. Furthermore, the factors significantly associated with Streptococcus mutans colonization include frequent exposure to sugar, frequent eating of snacks, taking sweetened drinks to bed, and sharing foods with adults and high levels of maternal Streptococcus mutans. In contrast multiple courses of antibiotics and tooth brushing are associated with non-colonization.15 The enamel of newly erupted teeth is immature and highly susceptible to caries until final maturation. The process of enamel maturation continues after a tooth has erupted and so the tooth becomes less susceptible to dental caries over time. Several factors including immunological factors, reduced saliva, defects of tooth tissues, developmental disturbances like pre-mature birth or low-birth weight, pre-and post natal infection/illness, nutritional deficiency and variety of environmental pollutants pre-dispose an individual, or a particular tooth to dental caries.16 Recent studies have suggested that breast-feeding per se is not significantly associated with ECC.17 Furthermore, with evidence indicating a weak relationship between bottle use and caries risk, it is likely that the risk of caries is due to the interaction of multiple factors.16 What are the consequences of not treating carious teeth? Pain Teeth with carious lesions involving the dentine give rise to pain when stimulated by food and drinks that are hot, cold and sweet. Untreated caries in the primary teeth will progress rapidly leading to acute inflammation of the dental pulp,18 ultimately inducing spontaneous pain. Children suffering from multiple carious teeth may develop a poor appetite because chewing becomes a painful experience. Preschool children with dental disease do not necessarily complain of pain; however, they do manifest the effects of pain in their altered eating and inability to sleep properly.19 Children with dental problems are more anxious when they visit a dentist for their first appointment.20 The stress from the pain of the toothache, disturbed sleep the previous night, the strange environment of the dental surgery and dental procedures lead to even more undesirable attitudes and behaviour in the child.21 Infection Untreated carious teeth are not only unsightly, they are also unhealthy. The resultant rough surface allows the stagnation of plaque and food debris which then promotes the development of a carious lesion in an adjacent tooth surface. This is particularly undesirable when a permanent tooth is erupting next to a carious primary tooth. Another problem is that the death of the pulp of a primary tooth leads to infection of the surrounding periapical and intra-radicular bone with acute episodes being capable of producing cellulitis. Chronic inflammation from pulpitis (inflammation of the dental pulp) and the presence of chronic abscesses affect growth via chronic inflammation affecting metabolic pathways where cytokines affect erythropoiesis. For example, interleukin-1 (IL-1), which encompasses a variety of actions in inflammation, can inhibit erythropoiesis causing suppression of haemoglobin production as a result of depressed erythrocyte production in the bone marrow leading to anaemia.22 Many years ago, Turner23 opined that an abscess on a primary tooth could cause local sepsis around the developing permanent successor; thus interfering with normal development and resulting in enamel defects on the permanent tooth. Subsequent studies have substantiated the relationship between abscesses on the primary molars and enamel defects on the succeeding permanent teeth.24 Therefore, long standing infection of this type can and, often does lead to unsightly discoloration and hypoplastic defects of the crowns of the permanent successor,23,24 which may even arrest the development of the underlying tooth germ.25 Other manifestations Other manifestations Consequences of ECC may go beyond pain and infection to a higher risk of new carious lesions in both the other primary teeth and those of the permanent dentition, emergency visits and hospitalizations, loss of school days with restricted activity, reduced ability to learn and increased treatment costs and time.26 Dental caries may have a significant impact on both the social and the psychological aspects of an individual's life affecting that individual's quality of life by impairing physical and social activities, as well as self-esteem.27 The condition may also affect a child's general health resulting in insufficient physical development especially in height and weight.28 Furthermore, it has been reported that children with ECC weigh less than 80% of their ideal body weight, and are in the 10th percentile for weight.28 By contrast, more recent data from USA indicates that children with a lot of carious teeth are overweight, probably due to the consumption of easily masticated fast foods that have high calorific value and sugar content. Acute abscesses related to primary teeth can lead to rare, but serious, sequelae such as sub-orbital cellulites, 29 brain abscesses30 and "unexplained" recurrent fevers.31 The 2000 National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Report32 stated that there appears to be a relationship between dental caries and acute otitis media, the exact biological mechanism is still not fully understood. Nevertheless, when a carious lesion occurs in a primary tooth, the permanent successor tooth is more than twice as likely to have a demarcated enamel defect and in cases of tooth extraction due to caries or an abscess the permanent successor tooth is five times more likely to have a demarcated defect of enamel.24

Discussion Dental caries is the result of infection with the causative microorganism Streptococcus mutans, which in most cases is transmitted vertically from the mother to her infant. Infants can be affected before the age of 12 months, and the earlier the infection the greater the caries risk. The addition of sweeteners to feeding bottles and other non-nutritive practices are more important contributors to caries risk than the use of infant formula or breast milk per se. A basic understanding of the importance of the primary dentition, the aetiology of caries and its consequences are necessary for medical practitioners, in order to be able to offer anticipatory advice (Table 5) to parents or caregivers and make necessary referrals to reduce the incidence of caries. Therefore, intervention to prevent or arrest ECC should focus on reducing the availability of refined carbohydrates (substrate), reducing the microbial burden (causative organism), increasing the resistance of the teeth (host) or a combination of these approaches.

Reducing the frequency of sugar intake; for example, by eliminating night time bottle feeding is an important preventive strategy. Educating parents and caregivers about the need for dietary modification has been shown to change the knowledge levels but have only a minor impact on long term feeding habits. This may be due to the fact that diet and infant feeding practices are profoundly influenced by cultural factors including social and family customs. Furthermore, parents are often confused by and find it difficult to determine the cariogenic potential of many advertised food and drinks products.16 Fluoride is a well established and researched agent which is widely used for the prevention and treatment of dental caries. It may be delivered in two ways: systemically or topically. Community water fluoridation has a wealth of research data to support its recommendation. As water makes contact with the teeth before becoming ingested (systemic), it has a topical effect by enhancing the replacement of minerals in the tooth surface. The use of fluoride dentifrices is acknowledged as being the major factor responsible for the worldwide reduction in the prevalence of caries in the past few decades. With increasing concern about fluorosis (a condition which manifests as an alteration in the translucency of enamel ranging from mild white flecking to brown mottling and pitting in the severe form) a pea-sized amount of a low concentration (i.e. 500-550ppm F) fluoride dentifrice is recommended for pre-schoolers. Nonetheless, it is mandatory to recommend twice daily brushing with a fluoride dentifrice to all patients, regardless of the risk level. Another approach in the prevention of dental caries is the suppression of Streptococcus mutans in the mouths of the child's primary caregiver (usually the mother). Chemical suppression by use of chlorhexidine gluconate in the form of mouthrinses, gels and dentifrices have been shown to reduce oral microorganisms. Xylitol appears to selectively impair the ability of Streptococcus mutans to adhere to the tooth surface thereby reducing the risk of transmission. Xylitol chewing gums have also been proven to be effective in reducing the numbers of Streptococcus mutans in children and their care givers. Nevertheless, parents of infants and toddlers should be encouraged to maintain their own oral health through treatment of existing disease and the use of fluorides and possibly xylitol chewing gum. Furthermore, they should be encouraged to reduce activities which increase the risk of early transmission of Streptococcus mutans like, sharing cups and utensils, tasting the child's food and cleaning pacifiers in their own mouths.16 Many parents remain unaware of the need to begin early regular dental care. Recently, Wu and her co-workers5 reported that one third of medical practitioners and half of the care-givers in Macau consider that infant oral hygiene practices and dental check-ups do not need to start early in a child's life. Although inadequate guidance on weaning and fluoride supplements by health care professionals are known to favour the development of ECC,33 the majority of the children in the USA are not examined by a dentist until they reach school age, by which time a dental examination become a necessity.34 A longitudinal cohort study demonstrated that among pre-school children who had their first preventive dental visit before one year of age were more likely to have subsequent preventive visits. Those who had their first preventive visit later had subsequent restorative and emergency visits.35 Therefore, due to their access to the general population, primary care physicians can play an important role in the prevention and control of dental caries and help the dental profession36 by referring children for oral health counselling, preferably soon after birth, but no later than 12 months of age.37 Despite a desire by physicians to play an active role in children's oral health, a national survey reported many paediatricians in the United States lacked the current scientific knowledge required to promote children's oral health38 and that 40.4% of children by age 5 years had at least one decayed or filled tooth.3 By comparison, in Hong Kong 49% of the 5 years old children were free from dental caries meaning that 51% had experienced dental caries. Therefore, medical practitioners with sound knowledge and positive attitude towards oral health can emphasize the importance of oral health to infant caregivers and motivate them to have positive dental attitudes. According to the Oral Health Survey 2001,4 utilization of oral health care services in Hong Kong by 5 years old children was low. Unfortunately, 72.2% of them had never visited a dentist and the reasons for the others visiting the dentist were toothache, an abscess or trauma, or suspected dental caries. Any child who suffers from dental caries should visit the dentist immediately so that proper treatment, involving restoration of the carious tooth or teeth can be provided and so that an appropriate preventive programme can be implemented to stop additional carious lesions from developing. Ideally, the first dental visit should be soon after the first tooth erupts and certainly before the eruption of all of the primary teeth. "Well-baby" visits are one way to provide an early, pleasant, and non-threatening introduction to oral health care and prevention for both parents and young children.39 This means that dental problems can then be prevented before they occur. The research evidence clearly indicates a need for early anticipatory advice40 to parents before their children's teeth begin to erupt. This advice can be effectively delivered by non-dental health-care providers who are more likely to see infants and toddlers before ECC occurs (Table 6). Nevertheless, early implementation of preventive care will provide long lasting benefits to the child's future oral health and should not be overlooked by medical practitioners, dentists and parents. Healthy, caries-free primary teeth create a healthy environment for the succeeding permanent teeth.

Conclusion It can be concluded that carious primary teeth should not be left untreated because of pain and consquences of infection that a child will suffer. Early recognition and referral, to a paediatric dentist, by a primary health care provider can ensure that the appropriate restorative treatment can be provided for the affected teeth. Key messages

Nigel M King, BDS, MSc(Hons), PhD, FDSRCS

Professor, Robert P Anthonappa, BDS, MDS (Paediatric Dentistry) Postgraduate Student for AdvDipPaediatrDent, Anut Itthagarun, DDS, PDipPaediatrDent, PhD Associate Professor, Paediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Professor Nigel M King, Paediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, Prince Philip Dental Hospital, Hong Kong.

References

|

|