|

January 2007, Volume 29, No. 1

|

Discussion Paper

|

Optimizing the psychopharmacotherapy of depression and medication adherence in primary careEdmund W W Lam 林永和 HK Pract 2007;29:16-23 Summary Evidence has shown that psychopharmacotherapy for patients with depression in primary care is effective. Inappropriate choice of medications and medication non-adherence are common in everyday practice. Nowadays, remission is considered as the treatment goal for depression and accurate diagnostic formulation, involving patient in management planning and rational choice of medications at different phases of treatment are pertinent. Medication adherence can be optimized through measures at drug, patient, doctor, family and community levels. Difficult cases should warrant referral and a collaborative care approach should be implemented into our primary care system. 摘要 在基層醫療中,以精神科藥物治療抑鬱症病人已有實證支持。然而,在日常醫療中, 藥物選擇不當及服藥依從性差,比比皆是。完全痊癒是目前治療抑鬱症的治療目標; 正確診斷、讓病人參與治療方案以及在治療不同階段合理選擇藥物,都十分重要。 通過在選擇藥物、病人、醫生、家庭和社區各方面採取措施,可望有效地改善服藥依從性。 困難病例需作轉介,而合作治療模式應在我們的基層醫療系統中推行。 Introduction Depression is an important public health topic across nations. In recent few years, the role of family physicians in combating depression has been increasingly recognized. Many interventions are considered effective, including psychotherapy and antidepressants.1 While most previous researches on clinical depression were based on secondary care patients, robust evidence supporting the use of antidepressants in primary care settings has been accumulating.2,3 A recent meta-analysis involving 3202 patients showed that remission rates in primary care studies of depression were at least as high as those in secondary settings.1 Nonetheless, in everyday practice, a significant proportion of patients did not reach remission as a consequence of inappropriate choice of medications. Studies have shown that medication non-adherence was common, ranging from 20 to 80%4 and this would further discount the favourable outcomes concluded in studies. This paper aims to discuss the optimization of psychopharmacotherapy of depression and medication adherence at the initiation, continuation and the maintenance phases of treatment. Starting from accurate diagnostic formulation Accurate diagnosis and comprehensive assessment are essential to the initiation of medications. While it is important for physicians to use diagnostic criteria for diagnosing clinical depression, focusing on searching a single diagnosis would reduce the complexity and also some of the reality of the problems.5 Assessment can be difficult as psychiatric diagnoses in primary care are usually contaminated with concurrent medical or psychiatric conditions, alcohol or substance abuse and life events such as bereavement.6 Not to miss the whole picture, the uniqueness of every patient should be respected and an individualized and clear documentation of the diagnostic formulation is advised:

Negotiating the management plan An ideal management plan is one that reflects the current best evidence on treatment, is tailored to the situation and preferences of the patient, and addresses emotional and social issues.7 Figure 1 illustrates the complex interplay of illness, doctor, patient and socio-economic factors around the management decision-making. The process of negotiation is often tedious and should be coupled with psychoeducation.

Figure 1: Negotiating the management plan There have been endless debates on the relative effectiveness of psychopharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatments in mental health care. As a guideline, patients with more severe depression and especially those with biological symptoms, such as weight loss, reduced appetite, mid or late insomnia, and morning worsening of mood, anhedonia, motor retardation or agitation, guilt and hopelessness are usually more responsive to antidepressants and so the use of antidepressant can be justified.8 While antidepressants have most effect in reducing symptoms, psychotherapies have more benefit in improving social maladjustment and interpersonal relationship and so a combined approach should be advocated.9 The explanatory models employed by the patients and their families have to be sought so that psychoeducation can be tailored to their ideas, misconceptions, concerns and needs. The quality of psychoeducation has been shown to significantly affect compliance, with a 60% adherence rate by patients who understood well their treatment regimen contrasting to an adherence rate of only 17% for those who were poorly informed.10 Patient-centred psychoeducation can help to alleviate any guilt, shame, hopelessness, unrealistic worries and criticisms. Key messages to be delivered include: (1) depression is a treatable, chronic, waxing and waning, and potentially fatal illness, (2) the neurobiological abnormalities interacting with psychosocial factors are the key causal factors, (3) antidepressants and other interventions are available treatments. The pros and cons for using these treatments, the time course of antidepressants' benefits, side effect profile with probability and reversibility of each side effect should be discussed. Adherence to treatment must be emphasized at the start and patients should be given some idea about the duration of treatment. Information leaflets should be provided to back up oral information. Optimizing psychopharmacotherapy at different phases of treatment

For depression, 4 treatment phases with different tasks to be achieved have been

identified -

1. Initiating with the right medications The World Health Organization has developed a guide to good prescribing for doctors to follow:12

To select the most proper medications for an individual patient out of the numerous available antidepressants can be a difficult task. Issues to be considered include (1) speed of onset of activity, (2) ease and flexibility of administration, including the ability to improve the response with higher dosages, (3) safety in a variety of patient types, such as elderly and those with concomitant diseases and conditions, (4) adherence and tolerance, (5) cost of a course of treatment, and (6) spectrum of efficacy.6 Several meta-analyses have concluded that all antidepressants have similar efficacy in the treatment of major depression.13-15 Yet, the 6 locally available SSRIs are all unique in their properties as they have significantly different affinities to the three major neurotransmitter transporters (serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine) involved in anxiety and depressive disorders. To serve as a guideline, Table 1 summarizes the differences for major classes of antidepressants in terms of their benefits on target symptoms and their common side effects by referring to surveys amongst Australian psychiatrists11,16 and comments from some local family physicians.

Table 1: Benefits of different classes of antidepressants on target symptoms and

their common side effects In clinical practice, many guidelines recommend SSRIs rather than TCAs, solely because of safety.3 While TCAs are far cheaper than SSRIs and medical cost is usually a great concern to patients particularly when they are not certain about the duration of treatment to be received, the estimated cost-effectiveness is similar or even higher for SSRIs after considering the issue of side effects.17 Dosing frequency is also an important consideration in selecting medication. A meta-analysis of 22 studies found single daily dosing regimen offers advantage over split dosing for simplicity, increased compliance, and reduced adverse effects.18 The dosing time should be adjusted to the time of maximal sedative properties of antidepressants (peak plasma concentration time after ingestion, T Max), such as Fluoxetine for morning and Mirtazapine about 2 hours before bedtime. Besides, using Mirtazapine in orally disintegrating tablet formulation and controlled-released formulations-Bupropion, Paroxetine, and Venlafaxine-were shown to be more accepted by patients.19,20 2. Achieving remission In research, a clinical response is defined as a 50% or greater reduction from baseline scores in rating scales such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.21 In everyday practice, a response may be gauged by the normalization of daily living, occupational and social function.22 Delay in onset of response by at least 1-2 weeks is universal for all antidepressants. There has been evidence showing that up to one-third of patients without improvement at first two weeks would gradually respond by eight weeks.15 An adequate antidepressant trial is defined as a trial in which an appropriate antidepressant is given in a sufficient dosage and duration, up to 12 weeks, to produce a response.23 Several studies have shown that 39% to 80% antidepressants were inadequately dosed in various healthcare settings.24,25 Reasons for suboptimal dosing may include side effects, fears of overdose or other toxicity, lack of confidence in higher dosages, and therapeutic nihilism.26 Patients do show diversity in response to the same SSRI. Non-response may be related to pharmacokinetic or pharmacogenomic factors.26 Patients who require higher than normal antidepressant dosages for response are known as "rapid metabolizers", as a result of genetic polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 enzymes.27 For all patients with depression, "the mission is remission" and the treatment goal should be aiming at recovering from all symptoms and returning to normal functioning.28,29 Untreated and inadequately treated patients are more likely to have higher risk of relapse, recurrence, chronicity, suicide, development of cardiovascular disease, and poor quality of life.1 Classical strategies for enhancing antidepressant efficacy to achieve remission include maximizing dosage, augmentation, combination and switching.26 While only a small number of evidence-based literature exists to guide the management of treatment-resistant depression in the past, the number of second-line treatment trials is increasing. The STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) trials are one amongst these trials to address on these second-line strategies by studying out-patients with non-psychotic depression in both primary and secondary care sites.30,31 It has shown that approximately 25% patients after unsuccessful treatment with an SSRI (Citalopram) achieved a remission of symptoms when switching to another antidepressant (Setraline, substained-released Bupropion or extended-released Venaflaxine).30 Augmentation of Citalopram with either sustained-release Bupropion or Buspirone also appears to be useful in actual clinical settings.31 These new evidences are exciting and family physicians may be tempted to manage difficult-to-treat depression themselves by employing various combination or augmentation strategies. However, as a general guideline, referral to psychiatrists should be considered for the interest of the patients under the following circumstances: an unclear diagnosis, severe or psychotic depression, tendency to harm oneself or others, co-existing alcoholism or pathological personality disorder, and failure of treatment (despite adequate duration and dosage).32 In addition, when remission is not achieved, incomplete case formulation ignoring psychosocial stressors and personality issues should also be considered and this necessitates combined treatment with psychological professionals and social workers. When remission is achieved, continuation therapy should be considered with reference to (1) how long the patient should stay on the drug, and (2) what other non-psychopharmacological strategies are necessary.9 A systemic review by Geddes et al33 has revealed the benefits of continuing treatment for 12 months or more by studying 31 randomized trials of continuing antidepressant treatment in 4410 depressive patients who have responded to the acute treatment. There was a 70% (95% CI 62-78;2p<00001) reduction in the odds of relapse for continuing antidepressant treatment for one year compared with treatment discontinuation regardless of the class of antidepressant and the heterogeneous groups of patients. In other words, this means that there is an approximately halving of the absolute risk for those patients who are still at appreciable risk of recurrence after 4-6 months of antidepressants to continue another year and probably a longer course of antidepressants.33 Severity of the episode and a strong family history of recurrence of depression also warrant longer duration of maintenance therapy.15 Nonetheless, the decision on the duration of antidepressant treatment should always be individualized by considering the patient's baseline risk, treatment preferences, burden of side-effects of medications and the doctor's prior beliefs.33 Discontinuation syndrome has been reported with abrupt withdrawal of an SSRI or TCA34 and for most SSRIs, except Fluoxetine, gradual discontinuation over one or two months is advisable. Patients should understand that they may need to take antidepressants during remission for "staying well" and withdrawal symptoms experienced from abrupt discontinuation should not be confused with antidepressant dependence. If feasible, collaboration with psychological professionals may reinforce treatment adherence through targeted psychotherapy. 3. Reducing premature discontinuation and non-adherence Early discontinuation was found in up to 44% of patients receiving antidepressant within the first 3 months of starting treatment in studies.35 In the continuation and maintenance phrase, medication non-adherence rate may be up to 80%.4 Whenever poor response or resistance is to be declared, likelihood of non-adherence must first be explored. Table 2 summarizes the factors contributing to medication non-adherence common to different phases of treatment. It serves as a checklist but by no means exhaustive to help correcting or preventing non-adherence.

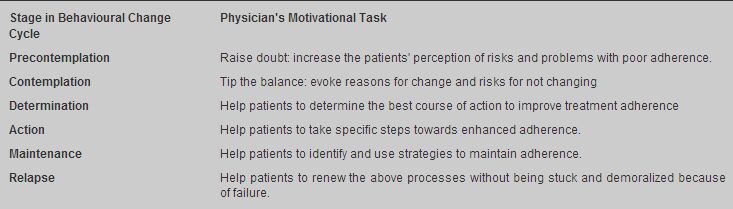

Table 2: Categories of causal factors of medication non-adherence a) At drug level - managing side effects Side effects are usually quoted as the best predictor of medication non-adherence amongst depressed patients in primary healthcare settings.36 Patients with depression are usually anxious about side effects of medications. It is therefore important to make them understand that there may be transient side effects upon initiation of SSRIs which will subside in weeks' time preceding the onset of their therapeutic effects. "Start low, go slow", maintaining at lowest therapeutic dosage, combining with benzodiazepines and frequent follow-up are common strategies employed to reduce drop-outs related to initiation side effects. To decrease the symptoms of agitation associated with antidepressant initiation, Benzodiazepines are quite commonly prescribed locally. Yet, rational use of Benzodiazepines should always be exercised to balance between the two extremes of inciting addiction and withholding effective treatment. The rule of thumb is to use Benzodiazepine only for short-term and to regularly review their use. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce peripheral manifestations of anxiety like tachycardia and tremor. Buspirone, despite having a more favourable adverse effect profile than Benzodiazepine, is less commonly prescribed locally. Newer hypnotics, Zopiclone and Zolpidem, have become first-line hypnotics but should be used intermittently and combined with sleep education and behavioural strategies. Weight gain usually will become unacceptable when patients go into remission. Varied sexual dysfunction including ejaculatory abnormality, decreased libido, male impotence, erectile dysfunction and anorgasmia amounting to 11% of 315 antidepressant trials is also a major reason for discontinuation.15 These side effects are usually hard to be dealt with and adjustment of dosages and switching medications, such as Bupoprion may be considered as it is devoid of serotoninergic effects and so associated with lower sexual side effects and weight loss. b) At clinic level - motivational strategies and practice management Although the literature provides inconclusive evidence about the effectiveness of different interventions to improve adherence, a patient-specific approach is often preferred.37 Motivational strategies were shown to increase treatment adherence by 23% in a metanalysis.38 Since motivation and confidence in the treatment given usually fluctuate with time, proper intervention should be implemented (Table 3).39 Non-adherence can be conceptualized as in the behaviour change model proposed by Prochaska and Diclemente, taking the assumption that we all naturally dislike taking medications and taking medication is a kind of behaviour change.39

Table 339: Matching intervention with motivational phase for changing

the behaviour of treatment non-adherence Accessibility to clinic bears much influence to medication adherence. For group practice, named-doctor approach can be considered to increase continuity of care. While visiting psychiatric outpatient clinics may be stigmatizing, primary care clinics also may deter patients by their crowdedness and the fast flow of patients. The environment of the waiting room and the attitude of the staffs can affect patients' attendance rate significantly. There are evidences indicating that services provided by trained primary care nurses could improve the outcome of guideline-concordant depression care.40 Besides, the clinic waiting time should be flexible and scheduled appointment system is advisable. Privacy and confidentiality should also be carefully observed. The consultation should be carried out in an undisturbed and relaxing room, with adequate time. Ideally, patients can be informed about the time blocked for their consultation before and extended consultation (30-45 minutes) can be arranged whenever necessary. c) At family and community level - collaborative care Collaboration is the current development trend for various health services. Collaborating with patients' significant others is essential as they may either inhibit or promote medication adherence. Enlisting their support is often beneficial not only to the patient but also to themselves. Families may remind patients about taking medication and follow-up appointments, as well as accompanying them to follow-ups. In community level, stigmatization of psychiatric illness remains a big reason to discourage patients to seek professional help and adhere to treatment. Patients' concern over disclosing their illnesses or not to their colleagues and friends is understandable and should be acknowledged. Discussion on how to communicate their illnesses to others can be made during consultation. Besides, another barrier to effective psychopharmacotherapy is that most local outpatient, disability and life insurance plans still exclude psychiatric diagnoses. Primary care in Hong Kong needs to be re-engineered by implementing collaborative care models involving different professionals, policy-makers, patients and their families. A recent systemic review41 in the USA showed that system level interventions implemented in patients willing to take antidepressants led to a modest increase in recovery rate. The tested system interventions were all employing a structured management plan and a multi-professional approach with inter-professional communication enhanced through meetings, supervisions and shared medical records.41 Although the findings may not be translated directly to Hong Kong, collaboration should be the right direction for the development of our primary care system. Conclusion New understanding in neurobiology and the advancement in psychopharmacotherapy have improved the outlook in our war against depression. Various drug, patient, doctor, family, and community factors leading to medication non-adherence should be anticipated and measures should be taken accordingly to correct them at different levels. Appropriate diagnoses, biopsychosocial formulation of problems, patient-centred assessment, involvement of patient in management planning, regular follow-up, empathic practice management and collaboration with family and professionals whenever necessary are pertinent to optimizing psychopharmacotherapy and medication adherence. Rational choice of the type of medications to be given at suitable dosages for adequate duration should be exercised with the current best evidence aiming at achieving remission in all patients with depression. Key messages

Edmund W W Lam, MBBS (HK), PDipComPsychMed (HKU), FRACGP, FHKCFP

Family Physician in Private Practice. Correspondence to : Dr Edmund W W Lam, G/F 125, Belcher's Street, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong. Email: lamwingwo@sinaman.com

References

|

|