|

January 2007, Volume 29, No. 1

|

Update Articles

|

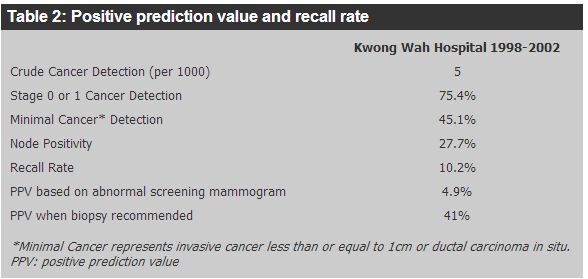

Cancer update - recent advances in screening and early diagnosis of breast cancerTing-ting Wong 黃亭亭 HK Pract 2007;29:3-9 Summary Breast cancer is the most common cancer affecting females in Hong Kong, but its mortality only ranks third. Although the incidence has doubled over the past ten years, the mortality rate has only increased slowly. This could be due to better treatment, but early detection was still one of the main contributing factors. The use of mammography is effective in diagnosing breast cancer early and thus in reducing mortality. Breast self examination raises the awareness of women of their own breasts to detect changes early. Ultrasound examination is an invaluable tool for breast surgeons in assessing breast lesions, but it is not a screening tool. MRI is also not a screening tool due to the high cost and over-sensitivity. 摘要 乳腺癌是香港婦女最常見的癌症,其死亡率排行第三。雖然病發率在過去十年倍增, 但死亡率只緩慢上升。這可能是由於有較佳的治療,但及早診斷仍是一個重要因素。 利用乳房X射線檢查能有效地為早期乳腺癌作出診斷,從而使死亡機會降低。 乳房自我檢查可提高婦女對自己乳房的關注和及早發現病變。 超聲波檢查是外科醫生評估乳房病情的重要工具,但它不宜用於普查。 因較為昂貴和靈敏度過高,乳房磁力共振成像術也不適合作為普查工具。 Introduction 1. Breast cancer Breast cancer has the highest incidence among all female cancers in Hong Kong since 1994.1 It accounted for 22% of all cancers in women in 2003. The number of breast cancer cases has risen markedly in the last 20 years and the figure has doubled over the last 10 years. From the Hospital Authority Hong Kong Cancer Registry, the incidence of breast carcinoma was 1,106 cases in 1991, it rose to 2,095 cases in 2001. In 2003, there were 2,106 new cases with an age standardized incidence rate of 45.4 per 100,000. Compared with other western countries, the incidence of breast cancer is about half, but it is the highest among Asian countries. The cumulative life-time risk is 1 in 23.2 Although it is uncommon to have breast cancer before the age of 25, we still occasionally encounter young patients even before their early twenties. The incidence rises rapidly and reaches its first peak at the 40 to 50 age group; it then continues to rise to its second peak at the 70 to 80 age group. An analysis of the age specific incidence rates showed that the biggest increase was in the 40 to 59 age group while those older than 60 showed only the smallest change. The incidence in the 40 to 55 age group accounted for 47.8% of all breast cancer in 2003.2 Despite the high incidence rate, breast cancer ranks third as the most common cause of cancer death among women in Hong Kong. There were 313 and 431 deaths due to breast cancer in 1993 and 2003 respectively. The mortality rate had increased very steadily and slowly. 2. Screening Breast cancer, though common, has good prognosis with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment. This has led many scientists and surgeons in the past to find good methods to screen the population and detect breast cancers early. It is important to note that the term "screening" in medical epidemiology refers to the routine examination of asymptomatic population for a disease. The principal purpose of screening for breast cancer is to reduce mortality from the disease through early diagnosis and treatment. These screening programmes are usually conducted, monitored and/ or supported by the government of a certain society/ community. The cost implication to the society at large is obvious. In Hong Kong, due to the lack of randomized control trial, the cost-effectiveness of such screening is difficult to assess, giving rise to controversies over the issue. To screen for breast cancer by the woman herself or by a medical practitioner means the detection of the disease on an individual basis. The line of thought, approach and cost implications are very different from those of a population wide screening programme. In this article, I will discuss the screening of breast cancer looking from these two different angles. Breast self examination (BSE) BSE in population wide screening programmes has so far yielded controversial results on its effectiveness in picking up breast cancers early. Whether it can improve survival remains unproven. In the two large population-based studies from Russia (388,535 women) and Shanghai (266,064 women) that compared women instructed on BSE with those with no instruction,3 there were no statistically significant differences in breast cancer mortality. In Russia, more cancers were found in the BSE group than in the control group while this was not the case in Shanghai. However, as stated in the Shanghai report, the level of practice of BSE was not known in trials outside the supervised sessions and they concluded that the Shanghai report was a trial of the teaching of BSE, not of the practice of BSE. It should not be inferred from the result of this study that there was no reduction in risk of dying from breast cancer if women practice BSE competently and frequently. Trials on the practice of BSE are difficult to conduct because it is difficult to randomize patients by asking the control group not to practice BSE. As shown by Feldman, tumour size at diagnosis is inversely associated with the frequency of BSE.4 BSE, however, requires no physicians and costs nothing. No screening test can replace the importance of patients' self awareness of their own health. In a modern society like Hong Kong, women have different sources of information on this very personal issue. Therefore appropriate instructions should be taught to women to examine their breasts. As mentioned in the Shanghai report, there is no reason to discourage women who choose to practice BSE from doing so. The main purpose of BSE is to make women aware of their own breasts to detect the changes in the breasts but not to make diagnosis on the lesion detected. Once changes are found, they should consult their doctors for assessment. Clinical breast examination (CBE) CBE by the family physician can diagnose about 60% of cancers detected by mammography, as well as some cancers not detected by mammography.5 >From the data shown by the Breast Care Centre in Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital, 5.2% of the cancers can be detected by CBE.6 However, no studies have directly tested the efficacy of CBE in decreasing breast cancer mortality and there is no firm evidence to support that CBE should be included or excluded in large scale breast cancer screening programmes.7 Whether a doctor can detect a breast mass depends on the size and consistency of the lesion, how frequent CBE is conducted, and his/her training and experience. Pre-menopausal women are best examined one week after onset of their last menstruation as the breast is least engorged. These limitations of CBE should be recognized. Mammography The most common means of breast screening is mammography. It can detect breast cancers when they are still clinically occult. At present, two views of each breast are taken: the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view and the craniocaudal (CC) view. Compression of the breast during the examination reduces the amount of tissue that must be penetrated to produce a better image. Calcifications can also be seen more clearly. Digital mammography is a more refined technique that produces images on a computer screen. The images can then be manipulated using magnification and contrast adjustment so that abnormal lesions can be picked up more easily. The commonly encountered signs of cancers on mammograms are masses, clustered microcalcifications, architectural distortions and asymmetries. Suspicious lesions are typically dense, speculated or have irregular borders. Some benign lesions also have their own typical features: for example, degenerating fibroadenomas have well-defined borders and gross inner calcifications. Suspicious calcifications are pinpoint, linear, or branched in character. Ordinarily, five or more calcifications clustered within 1 cm2 is considered a threshold for suspicion, and the risk of cancer increases with increases in the number of calcium specks in a cluster. Careful assessment of mammograms can pick up cancers as small as 2 to 3 mm in diameter. The detection of signs of malignancy in mammograms is largely dependent on the contrast between the lesion and its background. Breast cancers tend to be radiodense; the fatty radiolucent breasts of postmenopausal women provide the best background against which to detect cancers. Mammograms of young women with dense breast tissues are less useful. Paget's disease of the nipple and small intraductal cancers that present as bloody nipple discharge are often not detected in mammograms. The radiation dosage of a mammogram study is around 0.7 mSv, the dosage for a chest radiograph is 0.1 mSv and in the natural background we are exposed to 3 mSv/year. So screening mammography is a safe method and data suggests that there is probably no risk to the breast from radiation when such screening begins at the age of 40.8 Screening mammography can reduce the size and stage at detection of breast cancers9-11 and thus can result in reduction in cancer deaths.11 The Health Insurance Plan (HIP) of Greater New York trial is the first randomized trial of screening using mammograms.12 In 1963, 62,000 women aged 40 to 64 were enrolled in a health insurance programme. They were randomized to screening (study group) or to routine care (control group). The screening consisted of a two-view mammogram and a CBE. Members of the study group were offered an initial examination and three additional examinations at yearly intervals. The follow up continued for 18 years. Within 7 years after entry, 425 cases of breast cancers were diagnosed in the study group and there were 165 deaths. For the control group, 443 cases of breast cancer were diagnosed and 212 deaths were recorded. At year 10, mortality in the study group (breast cancer diagnosed within 5 to 7 years of the start of the study) was reduced by 30% compared with the control group. At year 18, the decrease was 23 to 24%. The reduction was statistically significant overall and for women aged 50 and older. The encouraging results of the HIP study have led to various projects: the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project (BCDDP) in USA in 1973,13 the Swedish Two-County Trial in 1977,16 the Edinburgh Trial (1979 to 1981)15 and the Canadian National Breast Screening Study (1980 to 1985).16,17 All demonstrated population wide screening programmes for breast cancer with mammography reduced mortality from 17 to 31 % The interval of screening was different in different studies, so was the age of screening. In general, reduction in mortality was consistently demonstrated for women aged 50 years and older. Questions about the quality of the trials reported were raised by Olsen and Gotzsche in 2000, 2001 and 2006.18-20 They identified baseline imbalances in six of the eight identified trials and inconsistencies in the number of women randomized in four of the trials. There was no effect of screening on improving breast cancer mortality in the two adequately randomized trials and the other six trials which had more favourable outcomes had not been randomized adequately. The controversy was obviously an important issue as different governments have spent millions of dollars in the screening programmes in the last two decades. In response to this uncertainty, major reviews have been conducted and a global summit on mammographic screening has been organised.21 It was concluded that the review of Olsen and Gotzsche was seriously flawed and provided no ground for the scientific community to alter the conclusion that breast cancer screening does indeed lead to a substantial reduction in mortality from the disease. The reviews also considered that there was no ground for stopping ongoing screening programmes nor planned programmes. The Working Group of the International Agency for Cancer Research (IARC) also concluded that trials had provided sufficient evidence for the efficacy of mammography screening between 50 and 69 years of age. For women aged 40 to 49 years, there was only limited evidence of mortality reduction. It was also concluded that the effectiveness of national screening programmes varied due to differences in coverage of the female population, quality of mammography, treatment and other factors.7 The United States Preventive Services Task Force, however, after assessing eight of the trials recommended screening mammography, with or without clinical breast examination, every 1 to 2 years for women aged 40 and older.22 The Swedish Overview concluded that the advantageous effect of breast screening in terms of breast cancer mortality in the age group 40 to 74 studied would persist after long-term follow-up.23 High rates of false positive results in screening mammograms had been an important concern. In one study, the sensitivity of mammography ranged from 83 to 95%.24 Elmore et al. reported a 49.1% cumulative false-positive risk, and an 18.6% rate of biopsy in healthy women after 10 mammograms.25 Approximately 6 to 7% of women are called for evaluation after the first screening. Most of them are found to be normal after taking several extra mammographic views and this recall rate drops significantly if they have previous mammograms for comparison.26,27 A positive screen inevitably leads to further confirmatory studies, ranging from a repeat mammogram to a biopsy. The anxiety and psychological trauma associated with these interventions can be considerable. Although most of the randomized control trials were from the western countries and some of the comments on mammographic screening argued on the low positive detection rate and high recall and biopsy rate. The screening statistics in the Well Women Center in Kwong Wah Hospital shows that the crude cancer detection rate is 5 per 1,000 women screened and this rate is higher in the age group 40 to 49 (Table 1).28 The recall rate is 10.2% and the positive predictive value is 41% when biopsy is recommended (Table 2).28 We also reported a detection rate of 27% last year.29

Putting aside the findings of population wide screening programmes for breast cancers, mammographic studies are indicated as part of the basic diagnostic examination of all symptomatic adult females when they have suspicious findings. Women at higher risks of developing breast cancer should also have regular mammographic studies. Risk factors include those with strong positive family history of breast cancer, those diagnosed to have breast cancer on one side of the breast, and those on hormonal replacement therapy. Demographic risk factors for breast cancer include advancing age, nulliparity, early menarche, late age at first birth, and late menopause.30 Breast ultrasound Ultrasound examination requires training and is very operator dependent; it cannot be used as a means for screening of breast cancers. Although some investigators have described the detection of cancer by ultrasound alone, it is not universally accepted. One prospective study by Kolb et al. at the Radiological Society of North America Meeting in 1996 reported a detection rate of 10 cancers in 2,300 women with radiologically dense breasts after a negative mammogram and clinical examination.31 Ultrasound is least accurate in detecting cancers in the fatty, postmenopausal breast and poor in detecting microcalcifications. In the author's experience, ultrasound is most useful in evaluating symptomatic dense breasts, non-palpable densities found on mammograms that suggest cysts, and equivocal physical findings when the mammogram is normal. It also helps to guide the fine needle aspiration procedure, especially for deep and small lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) MRI does not expose the patient to radiation but is expensive. It is particularly useful in high risk women with a 3% yield of cancer that can be found only on MRI after normal results on BSE and mammogram.32 MRI is very useful in examination of breasts with silicone prosthesis. It also helps to identify clinically occult tumours presented with a positive axillary lymph node. The true sensitivity and specificity of MRI for the evaluation of breast cancers remains uncertain and certainly it is not used as a screening tool. Tumour markers Most early breast cancers have normal breast cancer tumour markers (CA 15.3) level. They are only elevated when the tumour burden is high or when there is metastasis. It is not used as a screening tool. Discussion Discussion Breast cancer is a major public health issue. Although it is one of the leading causes of death in woman, it is less lethal than many other cancers. Moreover, many breast cancer patients do not die from the disease, partly due to other diseases associated with old age that cause death before breast cancer does, partly due to non-spreading of some of the cancers to other organs, and partly due to early detection and treatment before metastasizing of the cancer. The rationale of screening is to detect the cancer early enough so that treatment can alter the natural history to achieve cure or to prolong life. By screening, patients can also be benefited with reduction of the side effects arising from treatment by having lesser surgery or obviating the need to expose to chemotherapy. After forty years of clinical trials, breast screening has been proven to be an effective way of detecting breast cancer, thus reducing mortality. Although arguments for and against screening have been raised from time to time discussing the cost effectiveness, the anxiety and trauma of biopsy, there is no doubt that screening can reduce mortality. This scientific and medical fact should be made known to physicians and the general public, and screening should not be influenced by economic and political consideration. A certain individual if so wish should have the right to detect one's disease early, knowing the possible side effects of requiring repeated mammographic study and biopsy of benign lesions. Most of the data showed benefits of breast cancer screening for women aged 50 and older. For the age group 40 to 49 years, most of the published trials did not evaluate the screening benefits of this age group and WHO did not recommend screening at this age group. However, based on the fact that breast cancer rate climbs from age 40 years onward and also the bimodal distribution of breast cancer incidence observed in Hong Kong, we should not discourage women of this age group from screening but we will need randomize control trials in our locality to support this recommendation in the future. It is understandable that randomized controlled trials on BSE and CBE are difficult to conduct. The Shanghai report demonstrated that a mass programme on teaching of self examination in a society like Shanghai in the 80's did not improve reduction in mortality. However, the authors highlighted that one should not infer from their results that there would be no reduction in mortality if the patient practiced BSE competently and frequently. In fact motivated women should not be discouraged from practicing BSE. Many women care about their health and they visit their family physician for check up regularly, it is highly recommended that breast examination should be included in the yearly body check up. Conclusion Conclusion Despite so many debates and controversies, breast screenings are advocated and supported by the government of many western countries. Screening mammography is proven to be an effective tool and according to the bimodal distribution of breast cancer incidence observed in Hong Kong, screening mammography is recommended at 40 year old onward. Breast self examination is actually a part of breast awareness promotion, although no reduction in mortality can be demonstrated on mass teaching of breast self examination; the principle of breast self examination is to encourage women to be aware of one's own breasts by examining them monthly and to detect the changes if there is any. It does not require a mass teaching programme and any sophisticated technique. In fact motivated women should not be discouraged from practicing BSE. Many women care about their health and they visit their family physician for check up regularly; it is highly recommended that breast examination should be included in the yearly body check up. Key messages

Ting-ting Wong, MBBS(HK), FRCS(Edin), FCSHK, FHKAM (General Surgery)

Specialist in General Surgery Correspondence to : Dr Ting-ting Wong, 1304A, East Point Centre, 555 Hennessy Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong.

References

|

|